Torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for various reasons, including punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties.

Torturers more commonly act out of fear or due to limited resources than sadism. Although most torturers are thought to learn about torture techniques informally and rarely receive an explicit order, they are enabled by organizations that facilitate and encourage their behavior. Once a torture program is begun, it usually escalates beyond what is originally intended and often leads to involved agencies losing effectiveness. Torture aims to break the victim's will and destroy their agency and personality and is cited as one of the most damaging experiences that a person can undergo. Many victims suffer both physical damage—chronic pain is particularly common—and mental sequelae. Although torture survivors have among the highest rate of post-traumatic stress disorder, many are psychologically resilient.

Torture has been carried out since ancient times but in the

Definitions

Torture

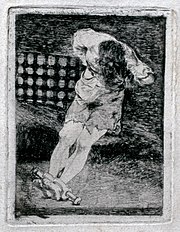

History

Pre-abolition

In most ancient, medieval, and early modern societies, torture was legally and morally acceptable.

Torture was rare in

Abolition and continued use

During the seventeenth century, torture remained legal in Europe, but its practice declined.

Torture was widely used by

Torture was also used by both communist and anti-communist governments during the

Prevalence

Most countries practice torture, although few acknowledge it.

Although liberal democracies are less likely to abuse their citizens, they may practice torture against marginalized citizens and non-citizens to whom they are not democratically accountable.

Torture is directed against certain segments of the population, who are denied the protection against torture that others enjoy.

Perpetrators

Since most research has focused on torture victims, less is known about the perpetrators of torture.

Although it is often assumed that torture is ordered from above at the highest levels of government,[78] sociologist Jonathan Luke Austin argues that government authorization is a necessary but not sufficient condition for torture to occur, given that a specific order to torture rarely can be identified.[79] In many cases, a combination of dispositional and situational effects lead a person to become a torturer.[77][80] In most cases of systematic torture, the torturers were desensitized to violence by being exposed to physical or psychological abuse during training[81][82][83] which can be a deliberate tactic to create torturers.[49] Even when not explicitly ordered by the government to torture,[84] perpetrators may feel peer pressure due to competitive masculinity.[85] Elite and specialized police units are especially prone to torturing, perhaps because of their tight-knit nature and insulation from oversight.[84] Although some torturers are formally trained, most are thought to learn about torture techniques informally.[86][49]

Torture can be a side effect of a broken criminal justice system in which underfunding, lack of

The contribution of bureaucracy to torture is under-researched and poorly understood.[49] Torturers rely on both active supporters and those who ignore it.[92] Military, intelligence, psychology, medical, and legal professionals can all be complicit in torture.[74] Incentives can favor the use of torture on an institutional or individual level, and some perpetrators are motivated by the prospect of career advancement.[93][94] Bureaucracy can diffuse responsibility for torture and help perpetrators excuse their actions.[81][95] Maintaining secrecy is often essential to maintaining a torture program, which can be accomplished in ways ranging from direct censorship, denial, or mislabeling torture as something else, to offshoring abuses to outside a state's territory.[96][97] Along with official denials, torture is enabled by moral disengagement from the victims and impunity for the perpetrators.[62] Public demand for decisive action against crime or even support for torture against criminals can facilitate its use.[65]

Once a torture program is begun, it is difficult or impossible to prevent it from escalating to more severe techniques and expanding to larger groups of victims, beyond what is originally intended or desired by decision-makers.

Purpose

Punishment

The use of torture for punishment dates back to antiquity, and is still employed in the 21st century.[19] A common practice in countries with dysfunctional justice systems or overcrowded prisons is for police to apprehend suspects, torture them, and release them without a charge.

The classification of

Deterrence

Torture may also be used indiscriminately to terrorize people other than the direct victim or to deter opposition to the government.

Confession

Torture has been used throughout history to extract confessions from detainees. In 1764, Italian reformer

Interrogation

The use of torture to obtain information during

Methods

A wide variety of techniques have been used for torture.[144] Nevertheless, there are a limited number of ways of inflicting pain while minimizing the risk of death.[145][60] Survivors report that the exact method used is not significant.[146] Most forms of torture include both physical and psychological elements[147][148] and multiple methods are typically used on one person.[149][60] Different methods of torture are popular in different countries.[150][60] Low-tech methods are more commonly used than high-tech ones, and attempts to develop scientifically validated torture technology have failed.[151] The prohibition of torture motivated a shift to methods that do not leave marks to aid in deniability and to deprive victims of legal redress.[152][153] As they faced more pressure and scrutiny, democracies led the innovation in clean torture practices in the early twentieth century; such techniques diffused worldwide by the 1960s.[154][21] Patterns of torture differ based on a torturer's time limits—for example, resulting from legal limits on pre-trial detention.[155]

Beatings or

Psychological torture includes methods that involve no physical element as well as forcing a person to do something and physical attacks that ultimately target the mind.

Effects

Torture is one of the most devastating experiences that a person can undergo.[174] Torture aims to break the victim's will[175] and destroy the victim's agency and personality.[176] Torture survivor Jean Améry argued that it was "the most horrible event a human being can retain within himself" and that "whoever was tortured, stays tortured".[177][178] Many torture victims, including Améry, later die by suicide.[179] Survivors often experience social and financial problems.[180] Circumstances such as housing insecurity, family separation, and the uncertainty of applying for asylum in a safe country strongly impact survivors' well-being.[181]

Death is not an uncommon outcome of torture.

Criminal prosecutions for torture are rare[189] and most victims who submit formal complaints are not believed.[190] Despite the efforts for evidence-based evaluation of the scars from torture such as the Istanbul Protocol, most physical examinations are inconclusive.[191] The effects of torture are one of several factors that usually result in inconsistent testimony from survivors, hampering their effort to be believed and secure either refugee status in a foreign country or criminal prosecution of the perpetrators.[192]

Although there is less research on the effects of torture on perpetrators,[193] they can experience moral injury or trauma symptoms similar to the victims, especially when they feel guilty about their actions.[194][195] Torture has corrupting effects on the institutions and societies that perpetrate it. Torturers forget important investigative skills because torture can be an easier way than time-consuming police work to achieve high conviction rates, encouraging the continued and increased use of torture.[196][194][197] Public disapproval of torture can harm the international reputation of countries that use it, strengthen and radicalize violent opposition to those states,[198][199][200] and encourage adversaries to themselves use torture.[201]

Public opinion

Studies have found that most people around the world oppose the use of torture in general.

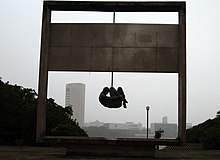

Prohibition

The condemnation of torture as barbaric and uncivilized originated in the debates around its abolition.[209] By the late nineteenth century, countries began to be condemned internationally for the use of torture.[210] The ban on torture became part of the civilizing mission justifying colonial rule on the pretext of ending torture,[211][212] despite the use of torture by colonial rulers themselves.[213] The condemnation was strengthened during the twentieth century in reaction to the use of torture by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.[214] Shocked by Nazi atrocities during World War II, the United Nations drew up the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which prohibited torture.[215][216] Torture is criticized on the basis of all major ethical frameworks, including deontology, consequentialism, and virtue ethics.[217][218] Some contemporary philosophers argue that torture is never morally acceptable; others propose exceptions to the general rule in real-life equivalents of the ticking time-bomb scenario.[219][220]

Torture stimulated the creation of the

The prohibition of torture is a

In

Prevention

Torture prevention is complicated both by lack of understanding about why torture occurs and by lack of application of what is known.

Sociologically, torture operates as a subculture, frustrating prevention efforts because torturers can find a way around rules.[243] Safeguards against torture in detention can be evaded by beating suspects during round-ups or on the way to the police station.[244][245] General training of police to improve their ability to investigate crime has been more effective at reducing torture than specific training focused on human rights.[246][247] Institutional police reforms have been effective when abuse is systematic.[248][249] Political scientist Darius Rejali criticizes torture prevention research for not figuring out "what to do when people are bad; institutions broken, understaffed, and corrupt; and habitual serial violence is routine".[250]

References

- Middle Latin tortura: "pain inflicted by judicial or ecclesiastical authority as a means of persuasion", ultimately from a Latin root meaning "to twist".[1]

- ^ Whitney & Smith 1897, p. 6396.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 396–397.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 394–395.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 96–97.

- ^ a b Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Nowak 2014, p. 392.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Saul & Flanagan 2020, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Nowak 2014, p. 391.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 3, 281.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b c Einolf 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Meyer et al. 2015, p. 11217.

- Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Frahm 2006, p. 81.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d e Evans 2020, History of Torture.

- ^ Beam 2020, p. 393.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Beam 2020, p. 392.

- ^ a b Einolf 2007, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Beam 2020, pp. 398, 405.

- ^ a b Beam 2020, p. 394.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 108.

- ^ a b Einolf 2007, p. 109.

- ^ Beam 2020, p. 400.

- ^ Einolf 2007, pp. 104, 109.

- ^ Beam 2020, p. 404.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 19.

- ^ a b Wisnewski 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Beam 2020, pp. 399–400.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 111.

- ^ Bourgon 2003, p. 851.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Einolf 2007, p. 112.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 24.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 94.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 38.

- ^ Einolf 2007, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Einolf 2023.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Kelly 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 182.

- ^ a b c d Carver & Handley 2016, p. 36.

- ^ a b Kelly et al. 2020, pp. 73, 79.

- ^ a b Jensena et al. 2017, pp. 406–407.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c Kelly et al. 2020, p. 65.

- ^ Kelly 2019, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d e Milewski et al. 2023.

- ^ a b Einolf 2007, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e Evans 2020, Political and Institutional Influences on the Practice of Torture.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 82.

- ^ Wolfendale 2019, p. 89.

- ^ a b Celermajer 2018, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Oette 2021, p. 307.

- ^ Kelly 2019, pp. 5, 7.

- ^ Oette 2021, p. 321.

- ^ a b Kelly et al. 2020, p. 70.

- ^ Oette 2021, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Austin 2022, p. 19.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b Wolfendale 2019, p. 92.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b Austin 2022, pp. 29–31.

- ^ a b Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 106.

- ^ Austin 2022, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Austin 2022, p. 25.

- ^ Austin 2022, p. 23.

- ^ a b Collard 2018, p. 166.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b Wisnewski 2010, pp. 193–194.

- ^ a b Rejali 2020, p. 90.

- ^ Austin 2022, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, p. 178.

- ^ a b Carver & Handley 2016, p. 633.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, p. 161.

- ^ a b Carver & Handley 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, p. 176.

- ^ Huggins 2012, pp. 47, 54.

- ^ Huggins 2012, p. 62.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 78–79, 90.

- ^ Huggins 2012, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Huggins 2012, pp. 57, 59–60.

- ^ Evans 2020, Conclusion.

- ^ Hassner 2020, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Wolfendale 2019, pp. 89–90, 92.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Collard 2018, pp. 158, 165.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 75, 82–83, 85.

- ^ Oette 2021, p. 331.

- ^ Kelly et al. 2020, p. 73.

- ^ Celermajer 2018, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Jensena et al. 2017, pp. 404, 408.

- ^ Kelly et al. 2020, p. 75.

- ^ Kelly et al. 2020, p. 74.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 408–409.

- ^ Nowak 2014, p. 393.

- ^ Bessler 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 414, 422, 427.

- ^ Bessler 2018, p. 33.

- ^ Evans 2020, The Definition of Torture.

- ^ a b Hajjar 2013, p. 23.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 270.

- ^ Young & Kearns 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 26, 38, 41.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 28.

- ^ Blakeley 2007, p. 392.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 38.

- ^ Hassner 2020, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Guarch-Rubio et al. 2020, pp. 69, 78.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Hajjar 2013, p. 22.

- ^ a b Einolf 2022, p. 11.

- ^ Rejali 2009, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 327.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 16.

- ^ Rejali 2009, pp. 461–462.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 362.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 92.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 4.

- ^ Rejali 2020, pp. 92–93, 106.

- ^ Houck & Repke 2017, pp. 277–278.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 24.

- ^ a b Einolf 2022, p. 2.

- ^ Einolf 2022, p. 3.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 71.

- ^ Hassner 2020, pp. 16, 20.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 410.

- ^ Einolf 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 110.

- ^ a b Pérez-Sales 2020, p. 432.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 421.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 420.

- ^ Rejali 2009, pp. 440–441.

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 443.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. xix.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 73.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 271–272.

- ^ a b Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 413.

- ^ a b Milewski et al. 2023, eFigure 3.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 411.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 414–415.

- ^ a b Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 418–419.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 421–422.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 423.

- ^ Einolf 2007, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 426–427.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 424–425.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2020, p. 114.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2020, pp. 163, 333.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 420.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 52.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2020, pp. 79, 115, 165.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2020, pp. 86–88.

- ^ a b Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 274.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 51.

- ^ Shue 2015, p. 120.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Hamid et al. 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Williams & Hughes 2020, pp. 133–134, 137.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 428.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 412.

- ^ Quiroga & Modvig 2020, p. 422.

- ^ Williams & Hughes 2020, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Williams & Hughes 2020, p. 136.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 130.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 84–86, 88.

- ^ Weishut & Steiner-Birmanns 2024, p. 88.

- ^ Weishut & Steiner-Birmanns 2024, p. 89.

- ^ Weishut & Steiner-Birmanns 2024, p. 94.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, pp. 53–55.

- ^ a b Rejali 2020, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 23.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 166.

- ^ Saul & Flanagan 2020, p. 370.

- ^ Blakeley 2007, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 22.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 21.

- ^ a b Rejali 2020, p. 81.

- ^ Houck & Repke 2017, p. 279.

- ^ Hatz 2021, pp. 683, 688.

- ^ Houck & Repke 2017, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 98.

- ^ a b Hatz 2021, p. 688.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 82.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 13, 42.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Kelly et al. 2020, p. 64.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 55.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 57.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 29.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Wisnewski 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Shue 2015, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Barnes 2017, p. 121.

- ^ Lesch 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Collard 2018, p. 162.

- ^ Evans 2020, Introduction.

- ^ a b Saul & Flanagan 2020, p. 356.

- ^ Pérez-Sales 2016, p. 82.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Thomson & Bernath 2020, pp. 474–475.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 631.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 387, 401.

- ^ Barnes 2017, pp. 60, 70.

- ^ Nowak 2014, p. 398.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 38.

- ^ Nowak 2014, pp. 397–398.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Thomson & Bernath 2020, p. 472.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Thomson & Bernath 2020, pp. 482–483.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 52.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 101.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Kelly 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Thomson & Bernath 2020, p. 488.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Carver & Handley 2016, p. 80.

- ^ Kelly 2019, p. 8.

- ^ Rejali 2020, p. 102.

Sources

Books

- Barnes, Jamal (2017). A Genealogy of the Torture Taboo. ISBN 978-1-351-97773-9.

- Carver, Richard; Handley, Lisa (2016). Does Torture Prevention Work?. ISBN 978-1-78138-868-6.

- Celermajer, Danielle (2018). The Prevention of Torture: An Ecological Approach. ISBN 978-1-108-63389-5.

- Collard, Melanie (2018). Torture as State Crime: A Criminological Analysis of the Transnational Institutional Torturer. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-45611-9.

- ISBN 978-0-415-51806-2.

- ISBN 978-1-317-20647-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-3087-9.

- Wisnewski, J. Jeremy (2010). Understanding Torture. ISBN 978-0-7486-8672-8.

- Whitney, William Dwight; Smith, Benjamin Eli (1897). OCLC 233135357.

- Young, Joseph K.; Kearns, Erin M. (2020). Tortured Logic: Why Some Americans Support the Use of Torture in Counterterrorism. ISBN 978-0-231-54809-0.

Book chapters

- ISBN 978-1-000-72592-6.

- Beam, Sara (2020). "Violence and Justice in Europe: Punishment, Torture and Execution". The Cambridge World History of Violence: Volume 3: AD 1500–AD 1800. Cambridge University Press. pp. 389–407. ISBN 978-1-107-11911-6.

- Evans, Rebecca (2020). "The Ethics of Torture: Definitions, History, and Institutions". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. ISBN 978-0-19-084662-6.

- Frahm, Eckart (2006). "Images of Assyria in 19th and 20th Century Scholarship". Orientalism, Assyriology and the Bible. Sheffield Phoenix Press. pp. 74–94. ISBN 978-1-905048-37-3.

- Kelly, Tobias; Jensen, Steffen; Andersen, Morten Koch (2020). "Fragility, states and torture". Research Handbook on Torture: Legal and Medical Perspectives on Prohibition and Prevention. ISBN 978-1-78811-396-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-163269-3.

- Pérez-Sales, Pau (2020). "Psychological torture". Research Handbook on Torture: Legal and Medical Perspectives on Prohibition and Prevention. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 432–454. ISBN 978-1-78811-396-0.

- Quiroga, José; Modvig, Jens (2020). "Torture methods and their health impact". Research Handbook on Torture: Legal and Medical Perspectives on Prohibition and Prevention. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 410–431. ISBN 978-1-78811-396-0.

- Rejali, Darius (2020). "The Field of Torture Today: Ten Years On from Torture and Democracy". Interrogation and Torture: Integrating Efficacy with Law and Morality. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–106. ISBN 978-0-19-009752-3.

- ISBN 978-1-78897-222-2.

- ISBN 978-1-315-74452-0.

- Thomson, Mark; Bernath, Barbara (2020). "Preventing Torture: What Works?". Interrogation and Torture: Integrating Efficacy with Law and Morality. Oxford University Press. pp. 471–492. ISBN 978-0-19-009752-3.

- Wolfendale, Jessica (2019). "The Making of a Torturer". The Routledge International Handbook of Perpetrator Studies. Routledge. pp. 84–94. ISBN 978-1-315-10288-7.

Journal articles

- ISSN 0026-9972.

- Bourgon, Jérôme (2003). "Abolishing 'Cruel Punishments': A Reappraisal of the Chinese Roots and Long-term Efficiency of the Xinzheng Legal Reforms". .

- Blakeley, Ruth (2007). "Why torture?" (PDF). .

- .

- Einolf, Christopher J. (2022). "How Torture Fails: Evidence of Misinformation from Torture-Induced Confessions in Iraq". .

- Einolf, Christopher J. (2023). "Understanding and Preventing Torture: a Review of the Literature". Human Rights Review. 24 (3): 319–338. S2CID 260663119.

- Guarch-Rubio, Marta; Byrne, Steven; Manzanero, Antonio L. (2020). "Violence and torture against migrants and refugees attempting to reach the European Union through Western Balkans". Torture. 30 (3): 67–83. ISSN 1997-3322.

- Hamid, Aseel; Patel, Nimisha; Williams, Amanda C. de C. (2019). "Psychological, social, and welfare interventions for torture survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". PMID 31550249.

- Hassner, Ron E. (2020). "What Do We Know about Interrogational Torture?". .

- Hatz, Sophia (2021). "What Shapes Public Support for Torture, and Among Whom?". .

- Houck, Shannon C.; Repke, Meredith A. (2017). "When and why we torture: A review of psychology research". Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 3 (3): 272–283. .

- Huggins, Martha K. (2012). "State Torture: Interviewing Perpetrators, Discovering Facilitators, Theorizing Cross-Nationally - Proposing "Torture 101"". State Crime Journal. 1 (1): 45–69. JSTOR 41917770.

- Jensena, Steffen; Kelly, Tobias; Andersen, Morten Koch; Christiansen, Catrine; Sharma, Jeevan Raj (2017). "Torture and Ill-Treatment Under Perceived: Human Rights Documentation and the Poor". Human Rights Quarterly. 39 (2): 393–415. ISSN 1085-794X.

- Kelly, Tobias (2019). "The Struggle Against Torture: Challenges, Assumptions and New Directions". .

- Lesch, Max (2023). "From Norm Violations to Norm Development: Deviance, International Institutions, and the Torture Prohibition". International Studies Quarterly. 67 (3). .

- Meyer, Christian; Lohr, Christian; Gronenborn, Detlef; Alt, Kurt W. (2015). "The massacre mass grave of Schöneck-Kilianstädten reveals new insights into collective violence in Early Neolithic Central Europe". PMID 26283359.

- Milewski, Andrew; Weinstein, Eliana; Lurie, Jacob; Lee, Annabel; Taki, Faten; Pilato, Tara; Jedlicka, Caroline; Kaur, Gunisha (2023). "Reported Methods, Distributions, and Frequencies of Torture Globally: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". JAMA Network Open. 6 (10): e2336629. PMID 37787994.

- Oette, Lutz (2021). "The Prohibition of Torture and Persons Living in Poverty: From the Margins to the Centre". ISSN 0020-5893.

- Weishut, Daniel J. N.; Steiner-Birmanns, Bettina (2024). "A Review of Reasons for Inconsistency in Testimonies of Torture Victims". Psychological Injury and Law. 17 (1): 88–98. ISSN 1938-971X.

- Williams, Amanda C. de C.; Hughes, John (2020). "Improving the assessment and treatment of pain in torture survivors". PMID 33456942.