Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and controls the public sphere and the private sphere of society. In the field of political science, totalitarianism is the extreme form of authoritarianism, wherein all socio-political power is held by a dictator, who also controls the national politics and the peoples of the nation with continual propaganda campaigns that are broadcast by state-controlled and by friendly private mass communications media.[1]

The totalitarian government uses ideology to control most aspects of human life, such as the

Definitions

Contemporary background

Modern political science catalogues three régimes of government: (i) the

There is much confusion about what is meant by totalitarian in the literature, including the denial that such [political] systems even exist. I define a totalitarian state as one with a system of government that is unlimited, [either]

Burma.

Totalitarianism is, then, a political ideology for which a totalitarian government is the agency for realizing its ends. Thus, totalitarianism characterizes such ideologies asBurma), Marxism–Leninism as in former East Germany, and Nazism. Even revolutionary Muslim Iran, since the overthrow of the Shah in 1978–79 has been totalitarian — here totalitarianism was married to Muslim fundamentalism. In short, totalitarianism is the ideology of absolute power. State socialism, Communism, Nazism, fascism, and Muslim fundamentalism have been some of its recent raiments. Totalitarian governments have been its agency. The state, with its international legal sovereignty and independence, has been its base. As will be pointed out, mortacracy is the result.[7][8]

- Degree of control

In exercising the power of government upon a society, the application of an official dominant ideology differenciates the worldview of the totalitarian régime from the worldview of the authoritarian régime, which is “only concerned with political power, and, as long as [government power] is not contested, [the authoritarian government] gives society a certain degree of liberty.”[3] Having no ideology to propagate, the politically secular authoritarian government “does not attempt to change the world and human nature”,[3] whereas the “totalitarian government seeks to completely control the thoughts and actions of its citizens”,[2] by way of an official “totalist ideology, a [political] party reinforced by a secret police, and monopolistic control of industrial mass society.”[3]

Historical background

From the right-wing perspective, the social phenomenon of political totalitarianism is a product of Modernism, which the philosopher Karl Popper said originated from humanist philosophy; from the republic (res publica) proposed by Plato in Ancient Greece (12th c. BC – 600 AD), from G.F.W. Hegel's conception of the State as a polity of peoples, and from the political economy of Karl Marx in the 19th century[9] — yet historians and philosophers of those periods dispute the historiographic accuracy of Popper’s 20-century interpretation and delineation of the historical origins of totalitarianism, because the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato did not invent the modern State.[10][11]

In the early 20th century,

In the essay “The ‘Dark Forces’, the Totalitarian Model, and Soviet History” (1987), by J.F. Hough,

American historian

After the Second World War (1937–1945), U.S. political discourse (domestic and foreign) included the concepts (ideologic and political) and the terms totalitarian, totalitarianism, and totalitarian model. In the post-war U.S. of the 1950s, in order to politically discredit the

Historiography

- Kremlinology

During the Russo–American Cold War (1945–1989), the academic field of

- Totalitarian model for policy

In the 1950s, the political scientist

In the 1960s, the revisionist Kremlinologists researched the organisations and studied the policies of the relatively autonomous

Politics of historical interpretation

The

New semantics

In 1980, in a book review of How the Soviet Union is Governed (1979), by J.F. Hough and Merle Fainsod, William Zimmerman said that “the Soviet Union has changed substantially. Our knowledge of the Soviet Union has changed, as well. We all know that the traditional paradigm [of the totalitarian model] no longer satisfies [our ignorance], despite several efforts, primarily in the early 1960s (the directed society, totalitarianism without police terrorism, the system of conscription) to articulate an acceptable variant [of Communist totalitarianism]. We have come to realize that models which were, in effect, offshoots of totalitarian models do not provide good approximations of post–Stalinist reality [of the USSR].”[33] In a book review of Totalitarian Space and the Destruction of Aura (2019), by Ahmed Saladdin, Michael Scott Christofferson said that Hannah Arendt’s interpretation of the USSR after Stalin was her attempt to intellectually distance her work from “the Cold War misuse of the concept [of the origins of totalitarianism]” as anti-Communist propaganda.[35]

In the essay, “Totalitarianism: Defunct Theory, Useful Word” (2010), the historian

In Revolution and Dictatorship: The Violent Origins of Durable Authoritarianism (2022), the political scientists

Politics

Early usages

- Italy

In 1923, in the early reign of Mussolini’s government (1922–1943), the anti-fascist academic Giovanni Amendola was the first Italian public intellectual to define and describe Totalitarianism as a régime of government wherein the supreme leader personally exercises total power (political, military, economic, social) as Il Duce of The State. That Italian fascism is a political system with an ideological, utopian worldview unlike the realistic politics of the personal dictatorship of a man who holds power for the sake of holding power.[2]

Later, the theoretician of Italian Fascism

Hannah Arendt, in her book "

For example, Victor Emmanuel III still reigned as a figurehead and helped play a role in the dismissal of Mussolini in 1943. Also, the Catholic Church was allowed to independently exercise its religious authority in Vatican City per the 1929 Lateran Treaty, under the leadership of Pope Pius XI (1922-1939) and Pope Pius XII (1939-1958).

- Britain

One of the first people to use the term totalitarianism in the English language was Austrian writer Franz Borkenau in his 1938 book The Communist International, in which he commented that it united the Soviet and German dictatorships more than it divided them.[45] The label totalitarian was twice affixed to Nazi Germany during Winston Churchill's speech of 5 October 1938 before the House of Commons, in opposition to the Munich Agreement, by which France and Great Britain consented to Nazi Germany's annexation of the Sudetenland.[46] Churchill was then a backbencher MP representing the Epping constituency. In a radio address two weeks later, Churchill again employed the term, this time applying the concept to "a Communist or a Nazi tyranny."[47]

- Spain

José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones, the leader of the historic Spanish reactionary party called the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA),[48] declared his intention to "give Spain a true unity, a new spirit, a totalitarian polity" and went on to say: "Democracy is not an end but a means to the conquest of the new state. When the time comes, either parliament submits or we will eliminate it."[49] General Francisco Franco was determined not to have competing right-wing parties in Spain and CEDA was dissolved in April 1937. Later, Gil-Robles went into exile.[50]

Politically matured by having fought and been wounded and survived the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), in the essay “Why I Write” (1946), the socialist George Orwell said, “the Spanish war and other events in 1936–37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.” That future totalitarian régimes would spy upon their societies and use the mass communications media to perpetuate their dictatorships, that “If you want a vision of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — forever.”[51]

- USSR

In the aftermath of the Second World War (1937–1945), in the lecture series (1945) and book (1946) titled The Soviet Impact on the Western World, the British historian

Cold War

In

- True belief

In

- Collaborationism

In “European Protestants Between Anti-Communism and Anti-Totalitarianism: The Other Interwar Kulturkampf?” (2018) the historian Paul Hanebrink said that Hitler's assumption of power in Germany in 1933 frightened Christians into anti-communism, because for European Christians, Catholic and Protestant alike, the new postwar ‘

Totalitarian model

In the U.S. geopolitics of the late 1950s, the Cold War concepts and the terms totalitarianism, totalitarian, and totalitarian model, presented in Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy (1956), by Carl Joachim Friedrich and Zbigniew Brzezinski, became common usages in the foreign-policy discourse of the U.S. Subsequently established, the totalitarian model became the analytic and interpretational paradigm for Kremlinology, the academic study of the monolithic police-state USSR. The Kremlinologists analyses of the internal politics (policy and personality) of the politburo crafting policy (national and foreign) yielded strategic intelligence for dealing with the USSR. Moreover, the U.S. also used the totalitarian model when dealing with fascist totalitarian régimes, such as that of a banana republic country.[57] As anti–Communist political scientists, Friedrich and Brzezinski described and defined totalitarianism with the monolithic totalitarian model of six interlocking, mutually supporting characteristics:

- Elaborate guiding ideology.

- One-party state

- State terrorism

- Monopoly control of weapons

- Monopoly control of the mass communications media

- Centrally directed and controlled planned economy[58]

Criticism of the totalitarian model

As traditionalist historians, Friedrich and Brzezinski said that the totalitarian régimes of government in the USSR (1917), Fascist Italy (1922–1943), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945) originated from the political discontent caused by the socio-economic aftermath of the First World War (1914–1918), which rendered impotent the government of

The historian of Nazi Germany, Karl Dietrich Bracher said that the totalitarian typology developed by Friedrich and Brzezinski was an inflexible model, for not including the revolutionary dynamics of bellicose people committed to realising the violent revolution required to establish totalitarianism in a sovereign state.[61] That the essence of totalitarianism is total control to remake every aspect of civil society using a universal ideology — which is interpreted by an authoritarian leader — to create a collective national identity by merging civil society into the State.[61] Given that the supreme leaders of the Communist, the Fascist, and the Nazi total states did possess government administrators, Bracher said that a totalitarian government did not necessarily require an actual supreme leader, and could function by way of collective leadership. The American historian Walter Laqueur agreed that Bracher’s totalitarian typology more accurately described the functional reality of the politburo than did the totalitarian typology proposed by Friedrich and Brzezinski.[62]

In Democracy and Totalitarianism (1968) the political scientist Raymond Aron said that for a régime of government to be considered totalitarian it can be described and defined with the totalitarian model of five interlocking, mutually supporting characteristics:

- A one-party state where the ruling party has a monopoly on all political activity.

- A state ideology upheld by the ruling party that is given official status as the only authority.

- A state monopoly on information; control of the mass communications media to broadcast the official truth.

- A state-controlled economy featuring major economic entities under state control.

- An ideological police-state terror; criminalisation of political, economic, and professional activities.[66]

Post–Cold War

Laure Neumayer posited that "despite the disputes over its heuristic value and its normative assumptions, the concept of totalitarianism made a vigorous return to the political and academic fields at the end of the Cold War."[68] In the 1990s, François Furet made a comparative analysis[69] and used the term totalitarian twins to link Nazism and Stalinism.[70][71][72] Eric Hobsbawm criticised Furet for his temptation to stress the existence of a common ground between two systems with different ideological roots.[73] In Did Somebody Say Totalitarianism?: Five Interventions in the (Mis)Use of a Notion, Žižek wrote that "[t]he liberating effect" of General Augusto Pinochet's arrest "was exceptional", as "the fear of Pinochet dissipated, the spell was broken, the taboo subjects of torture and disappearances became the daily grist of the news media; the people no longer just whispered, but openly spoke about prosecuting him in Chile itself."[74] Saladdin Ahmed cited Hannah Arendt as stating that "the Soviet Union can no longer be called totalitarian in the strict sense of the term after Stalin's death", writing that "this was the case in General August Pinochet's Chile, yet it would be absurd to exempt it from the class of totalitarian regimes for that reason alone." Saladdin posited that while Chile under Pinochet had no "official ideology", there was one man who ruled Chile from "behind the scenes", "none other than Milton Friedman, the godfather of neoliberalism and the most influential teacher of the Chicago Boys, was Pinochet's adviser." In this sense, Saladdin criticised the totalitarian concept because it was only being applied to "opposing ideologies" and it was not being applied to liberalism.[35]

In the early 2010s, Richard Shorten, Vladimir Tismăneanu, and Aviezer Tucker posited that totalitarian ideologies can take different forms in different political systems but all of them focus on utopianism, scientism, or political violence. They posit that Nazism and Stalinism both emphasised the role of specialisation in modern societies and they also saw polymathy as a thing of the past, and they also stated that their claims were supported by statistics and science, which led them to impose strict ethical regulations on culture, use psychological violence, and persecute entire groups.[75][76][77] Their arguments have been criticised by other scholars due to their partiality and anachronism. Juan Francisco Fuentes treats totalitarianism as an "invented tradition" and he believes that the notion of "modern despotism" is a "reverse anachronism"; for Fuentes, "the anachronistic use of totalitarian/totalitarianism involves the will to reshape the past in the image and likeness of the present."[78]

Other studies try to link modern technological changes to totalitarianism. According to

In 2016,

Religious totalitarianism

Islamic

The Taliban is a totalitarian Sunni Islamist militant group and political movement in Afghanistan that emerged in the aftermath of the Soviet–Afghan War and the end of the Cold War. It governed most of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 and returned to power in 2021, controlling the entirety of Afghanistan. Features of its totalitarian governance include the imposition of Pashtunwali culture of the majority Pashtun ethnic group as religious law, the exclusion of minorities and non-Taliban members from the government, and extensive violations of women's rights.[90]

The

Christian

The city of Geneva under John Calvin's leadership has also been characterised as totalitarian by scholars.[104][105][106]

Revisionist school of Soviet-period history

- Soviet society after Stalin

The death of Stalin in 1953 voided the simplistic totalitarian model of the police-state USSR as the epitome of the totalitarian state.[107] A fact common to the revisionist-school interpretations of the reign of Stalin (1927–1953) was that the USSR was a country with weak social institutions, and that state terrorism against Soviet citizens indicated the political illegitimacy of Stalin's government.[107] That the citizens of the USSR were not devoid of personal agency or of material resources for living, nor were Soviet citizens psychologically atomised by the totalist ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union[108] — because “the Soviet political system was chaotic, that institutions often escaped the control of the centre, and that Stalin’s leadership consisted, to a considerable extent, in responding, on an ad hoc basis, to political crises as they arose.”[109] That the legitimacy of Stalin’s régime of government relied upon the popular support of the Soviet citizenry as much as Stalin relied upon state terrorism for their support. That by politically purging Soviet society of anti–Soviet people Stalin created employment and upward social mobility for the post–War generation of working class citizens for whom such socio-economic progress was unavailable before the Russian Revolution (1917–1924). That the people who benefited from Stalin's social engineering became Stalinists loyal to the USSR; thus, the Revolution had fulfilled her promise to those Stalinist citizens and they supported Stalin because of the state terrorism.[108]

- German Democratic Republic (GDR)

In the case of East Germany, (0000) Eli Rubin posited that East Germany was not a totalitarian state but rather a society shaped by the confluence of unique economic and political circumstances interacting with the concerns of ordinary citizens.[110]

Writing in 1987, Walter Laqueur posited that the revisionists in the field of Soviet history were guilty of confusing popularity with morality and of making highly embarrassing and not very convincing arguments against the concept of the Soviet Union as a totalitarian state.[111] Laqueur stated that the revisionists' arguments with regard to Soviet history were highly similar to the arguments made by Ernst Nolte regarding German history.[111] For Laqueur, concepts such as modernisation were inadequate tools for explaining Soviet history while totalitarianism was not.[112] Laqueur's argument has been criticised by modern "revisionist school" historians such as Paul Buhle, who said that Laqueur wrongly equates Cold War revisionism with the German revisionism; the latter reflected a "revanchist, military-minded conservative nationalism."[113] Moreover, Michael Parenti and James Petras have suggested that the totalitarianism concept has been politically employed and used for anti-communist purposes. Parenti has also analysed how "left anti-communists" attacked the Soviet Union during the Cold War.[114] For Petras, the CIA funded the Congress for Cultural Freedom in order to attack "Stalinist anti-totalitarianism."[115] Into the 21st century, Enzo Traverso has attacked the creators of the concept of totalitarianism as having invented it to designate the enemies of the West.[116]

According to some scholars, calling Joseph Stalin totalitarian instead of authoritarian has been asserted to be a high-sounding but specious excuse for Western self-interest, just as surely as the counterclaim that allegedly debunking the totalitarian concept may be a high-sounding but specious excuse for Russian self-interest. For Domenico Losurdo, totalitarianism is a polysemic concept with origins in Christian theology and applying it to the political sphere requires an operation of abstract schematism which makes use of isolated elements of historical reality to place fascist regimes and the Soviet Union in the dock together, serving the anti-communism of Cold War-era intellectuals rather than reflecting intellectual research.[117]

See also

- List of totalitarian regimes

- Comparison of Nazism and Stalinism

- Democratic backsliding

- Economic totalitarianism

- List of authoritarian states

- List of cults of personality

- Totalitarian architecture

- Nazism

- Fascism

- Stalinism

- Authoritarianism

References

- ^ ISBN 0393048187.

- ^ ISBN 0394502426.

- ^ ISBN 978-1848851665.

- OCLC 1172052725.

- ISBN 978-1-135-93226-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7391-7659-7. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ISBN 9781351294089.

- S2CID 145155872.

- ISBN 978-0691158136. Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Wild, John (1964). Plato’s Modern Enemies and the Theory of Natural Law. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 23. “Popper is committing a serious historical error in attributing the organic theory of the State to Plato, and accusing him of all the fallacies of post–Hegelian and Marxist historicism — the theory that history is controlled by the inexorable laws governing the behaviour of superindividual social entities of which human beings and their free choices are merely subordinate manifestations.”

- ^ Levinson, Ronald B. (1970). In Defense of Plato. New York: Russell and Russell. p. 20. “In spite of the high rating, one must accord his [Popper’s] initial intention of fairness, his hatred for the enemies of the ‘open society’, his zeal to destroy whatever seems, to him, destructive of the welfare of mankind, has led him into the extensive use of what may be called terminological counter-propaganda. . . . With a few exceptions in Popper’s favour, however, it is noticeable that [book] reviewers possessed of special competence in particular fields — and here Lindsay is again to be included — have objected to Popper’s conclusions in those very fields. . . . Social scientists and social philosophers have deplored his radical denial of historical causation, together with his espousal of Hayek’s systematic distrust of larger programs of social reform; historical students of philosophy have protested his [Popper’s] violent, polemical handling of Plato, Aristotle, and, particularly, Hegel; ethicists have found contradictions in the ethical theory (‘critical dualism’) upon which his [anti-Modernist] polemic is largely based.”

- ^ a b Gentile, Giovanni; Mussolini, Benito (1932). La dottrina del fascismo [The Doctrine of Fascism].

- ISBN 978-0804736336. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- JSTOR 130293.

- ISBN 9781793605344. Archivedfrom the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 9788481028898. Archivedfrom the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 9780817979331. Archivedfrom the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 9781487590116. Archivedfrom the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via Google Books.

- from the original on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2022-04-24. Retrieved April 8, 2022

- ISBN 0226738868.

- ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5.

- ISBN 978-9042005525.

Concepts of totalitarianism became most widespread at the height of the Cold War. Since the late 1940s, especially since the Korean War, they were condensed into a far-reaching, even hegemonic, ideology, by which the political elites of the Western world tried to explain and even to justify the Cold War constellation.

- ISBN 978-0231131247.

The opposition between the West and Soviet totalitarianism was often presented as an opposition both moral and epistemological between truth and falsehood. The democratic, social, and economic credentials of the Soviet Union were typically seen as 'lies' and as the product of deliberate and multiform propaganda. ... In this context, the concept of totalitarianism was itself an asset. As it made possible the conversion of prewar anti-fascism into postwar anti-communism.

- ISBN 978-0521546898.

- ISBN 978-0714683614.

- ISBN 978-1412831369. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ISBN 978-1139446631.

Academic Sovietology, a child of the early Cold War, was dominated by the 'totalitarian model' of Soviet politics. Until the 1960s it was almost impossible to advance any other interpretation, in the USA at least.

- S2CID 142829949.

- ^ ISBN 978-1139446631.

Tucker's work stressed the absolute nature of Stalin's power, an assumption which was, increasingly, challenged by later revisionist historians. In his Origins of the Great Purges, Arch Getty argued that the Soviet political system was chaotic, that institutions often escaped the control of the centre, and that Stalin's leadership consisted to a considerable extent in responding, on an ad hoc basis, to political crises as they arose. Getty's work was influenced by political [the] science of the 1960s onwards, which, in a critique of the totalitarian model, began to consider the possibility that relatively autonomous bureaucratic institutions might have had some influence on policy-making at the highest level.

- ISSN 1468-2303.

. . . the Western scholars who, in the 1990s and 2000s, were most active in scouring the new archives for data on Soviet repression were revisionists (always 'archive rats') such as Arch Getty and Lynne Viola.

- ISBN 978-1139446631.

In 1953, Carl Friedrich characterised totalitarian systems in terms of five points: an official ideology, control of weapons and of media, use of terror, and a single mass party, 'usually under a single leader.' There was, of course, an assumption that the leader was critical to the workings of totalitarianism: at the apex of a monolithic, centralised, and hierarchical system, it was he who issued the orders which were fulfilled, unquestioningly, by his subordinates.

- S2CID 142829949.

- ^ JSTOR 2497167.

- ^ ISBN 1893554724.

- ^ ISBN 978-1438472935.

- ^ S2CID 143510612.

- ISBN 978-0691169521.

- ^ Rummel, R.J. (1994). "Democide in Totalitarian States: Mortacracies and Megamurderers.". In Charney, Israel W. (ed.). Widening circle of genocide. Transaction Publishers. p. 5.

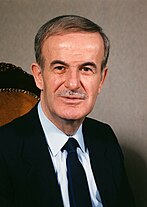

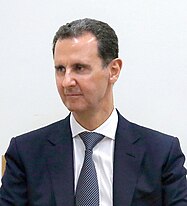

- ^ Sources:

- Wieland, Carsten (2018). "6: De-neutralizing Aid: All Roads Lead to Damascus". Syria and the Neutrality Trap: The Dilemmas of Delivering Humanitarian Aid Through Violent Regimes. 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK: I. B. Tauris. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7556-4138-3.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link

- Wieland, Carsten (2018). "6: De-neutralizing Aid: All Roads Lead to Damascus". Syria and the Neutrality Trap: The Dilemmas of Delivering Humanitarian Aid Through Violent Regimes. 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK: I. B. Tauris. p. 68.

- Meininghaus, Esther (2016). Creating Consent in Ba'thist Syria: Women and Welfare in a Totalitarian State. London, UK: I. B. Tauris. pp. 69, 70. ISBN 978-1-78453-115-7.

- Hashem, Mazen (Spring 2012). "The Levant Reconciling a Century of Contradictions". AJISS. 29 (2): 141. Archived from the original on 5 March 2024 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Sources:

- Tucker, Ernest (2019). "21: Middle East at the End of the Cold War, 1979–1993". The Middle East in Modern World History (Second ed.). 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA: Routledge. p. 303. LCCN 2018043096.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link

- Tucker, Ernest (2019). "21: Middle East at the End of the Cold War, 1979–1993". The Middle East in Modern World History (Second ed.). 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA: Routledge. p. 303.

- Kirkpatrick, Jeane J (1981). "Afghanistan: Implications for Peace and Security". World Affairs. 144 (3): 243. JSTOR 20671902– via JSTOR.

- S.Margolis, Eric (2005). "2: The Bravest Men on Earth". War at the top of the World. 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001, USA: Routledge. pp. 14, 15. ISBN 0-415-92712-9.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link - ISBN 978-0299080600.

- ISBN 0195071328.

- ^ Arendt 1958, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Arendt 1958, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Nemoianu, Virgil (December 1982). "Review of End and Beginnings". Modern Language Notes. 97 (5): 1235–1238.

- ^ Churchill, Winston (5 October 1938). The Munich Agreement (Speech). House of Commons of the United Kingdom: International Churchill Society. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

We in this country, as in other Liberal and democratic countries, have a perfect right to exalt the principle of self-determination, but it comes ill out of the mouths of those in totalitarian states who deny even the smallest element of toleration to every section and creed within their bounds. Many of those countries, in fear of the rise of the Nazi power, ... loathed the idea of having this arbitrary rule of the totalitarian system thrust upon them, and hoped that a stand would be made.

- ^ Churchill, Winston (16 October 1938). Broadcast to the United States and to London (Speech). International Churchill Society. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-0521831314. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ISBN 978-0393329872.

- ISBN 978-0810880092. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Orwell, George (1946). "Why I Write". Gangrel. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ISBN 0684189038.

- ISBN 0521645719.

- ISBN 0060505915.

- S2CID 158028188.

- S2CID 158028188.

- ISBN 978-0674332607.

- ^ Brzezinski & Friedrich, 1956, p.22.

- ^ Brzezinski & Friedrich 1956, p.22.

- ISBN 978-0684189031.

- ^ OCLC 43419425.

- ISBN 978-0684189031.

- ISBN 978-0-19-976441-9.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-226-33337-3.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - ISBN 978-1-78453-115-7.

- ISBN 978-0297002529.

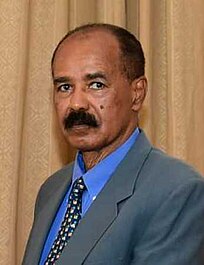

- ^ Saad, Asma (21 February 2018). "Eritrea's Silent Totalitarianism". McGill Journal of Political Studies (21). Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ISBN 9781351141741.

- S2CID 143074271.

- ^ Singer, Daniel (17 April 1995). "The Sound and the Furet". The Nation. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

Furet, borrowing from Hannah Arendt, describes Bolsheviks and Nazis as totalitarian twins, conflicting yet united.

- ^ Singer, Daniel (2 November 1999). "Exploiting a Tragedy, or Le Rouge en Noir". The Nation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

... the totalitarian nature of Stalin's Russia is undeniable.

- ^ Grobman, Gary M. (1990). "Nazi Fascism and the Modern Totalitarian State". Remember.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

The government of Nazi Germany was a fascist, totalitarian state.

- ISBN 978-0349120560.

- ISBN 9781859844250.

- ISBN 978-0230252073.

- ISBN 978-0520954175.

- ISBN 978-1316393055.

- S2CID 155157905.

- OCLC 1049577294.

- ISBN 978-1526600196.

- S2CID 6826824.

- ^ "China invents the digital totalitarian state". The Economist. 17 December 2017. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Leigh, Karen; Lee, Dandan (2 December 2018). "China's Radical Plan to Judge Each Citizen's Behavior". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ Lucas, Rob (January–February 2020). "The Surveillance Business". New Left Review. 121. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Brennan-Marquez, K. (2012). "A Modest Defence of Mind Reading". Yale Journal of Law and Technology. 15 (214). Archived from the original on 2020-08-10.

- ^ Pickett, K. (16 April 2020). "Totalitarianism: Congressman calls method to track coronavirus cases an invasion of privacy". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ISBN 978-3319908694.)

- S2CID 19208453.

- .

- S2CID 253945821.

Afghanistan is now controlled by a militant group that operates out of a totalitarian ideology.

- Madadi, Sayed (6 September 2022). "Dysfunctional centralization and growing fragility under Taliban rule". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

In other words, the centralized political and governance institutions of the former republic were unaccountable enough that they now comfortably accommodate the totalitarian objectives of the Taliban without giving the people any chance to resist peacefully.

- Sadr, Omar (23 March 2022). "Afghanistan's Public Intellectuals Fail to Denounce the Taliban". Fair Observer. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

The Taliban government currently installed in Afghanistan is not simply another dictatorship. By all standards, it is a totalitarian regime.

- "Dismantlement of the Taliban regime is the only way forward for Afghanistan". Atlantic Council. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

As with any other ideological movement, the Taliban's Islamic government is transformative and totalitarian in nature.

- Akbari, Farkhondeh (7 March 2022). "The Risks Facing Hazaras in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan". George Washington University. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

In the Taliban's totalitarian Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, there is no meaningful political inclusivity or representation for Hazaras at any level.

- Madadi, Sayed (6 September 2022). "Dysfunctional centralization and growing fragility under Taliban rule". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Yusuf al-Qaradawi stated: "[The] declaration issued by the Islamic State is void under sharia and has dangerous consequences for the Sunnis in Iraq and for the revolt in Syria", adding that the title of caliph can "only be given by the entire Muslim nation", not by a single group./>Strange, Hannah (5 July 2014). "Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi addresses Muslims in Mosul". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ Bunzel, Cole (27 November 2019). "Caliph Incognito: The Ridicule of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi". www.jihadica.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Hamid, Shadi (1 November 2016). "What a caliphate really is—and how the Islamic State is not one". Brookings. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Winter, Charlie (27 March 2016). "Totalitarianism 101: The Islamic State's Offline Propaganda Strategy".

- ISBN 9780367457631.

- ^ Peter, Bernholz (February 2019). "Supreme Values, Totalitarianism, and Terrorism". The Oxford Handbook of Public Choice. Vol. 1.

- ^ Haslett, Allison (2021). "The Islamic State: A Political-Religious Totalitarian Regime". Scientia et Humanitas: A Journal of Student Research. Middle Tennessee State University.

Islamic State embraces the most violent, extreme traits of Jihadi-Salafism.. the State merged religious dogma and state control together to create a political-religious totalitarian regime that was not bound by physical borders

- ISBN 978-8493914394. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-10-05. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- ^ "Franco edicts". Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2005.

- ISBN 978-0-299-11070-3.

- ^ Jensen, Geoffrey. "Franco: Soldier, Commander, Dictator". Washington D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2005. p. 110-111.

- ^ Reuter, Tim (19 May 2014). "Before China's Transformation, There Was The 'Spanish Miracle'". Forbes Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ Payne (2000), p. 645

- ISBN 978-3-319-56907-9. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ISBN 978-0-19-046974-0. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ISBN 978-1-134-06346-8. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ ISBN 978-0684189031.

- ^ ISBN 978-0195050004.

- ISBN 978-1-139-44663-1.

- ISBN 978-1469606774.

- ^ ISBN 978-0684189031.

- ISBN 978-0684189031.

- ISBN 0349120560.

- ISBN 978-0872863293.

- from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ISBN 978-2020378574.

- .

Notes

Further reading

- Arendt, Hannah (1958). The Origins of Totalitarianism (Second Enlarged ed.). New York, USA: Meridian Books. LCCN 58-11927.

- Armstrong, John A. The Politics of Totalitarianism (New York: Random House, 1961).

- Béja, Jean-Philippe (March 2019). "Xi Jinping's China: On the Road to Neo-totalitarianism". Social Research: An International Quarterly. 86 (1): 203–230. ProQuest 2249726077. Archivedfrom the original on December 3, 2022.

- Bernholz, Peter. "Ideocracy and totalitarianism: A formal analysis incorporating ideology", Public Choice 108, 2001, pp. 33–75.

- Bernholz, Peter. "Ideology, sects, state and totalitarianism. A general theory". In: H. Maier and M. Schaefer (eds.): Totalitarianism and Political Religions, Vol. II (Routledge, 2007), pp. 246–270.

- Borkenau, Franz, The Totalitarian Enemy (London: Faber and Faber 1940).

- ISBN 0804692688.

- Congleton, Roger D. "Governance by true believers: Supreme duties with and without totalitarianism." Constitutional Political Economy 31.1 (2020): 111–141. online

- Connelly, John. "Totalitarianism: Defunct Theory, Useful Word" Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 11#4 (2010) 819–835. online.

- Curtis, Michael. Totalitarianism (1979) online

- Devlin, Nicholas. "Hannah Arendt and Marxist Theories of Totalitarianism." Modern Intellectual History (2021): 1–23 online.

- Diamond, Larry. "The road to digital unfreedom: The threat of postmodern totalitarianism." Journal of Democracy 30.1 (2019): 20–24. excerpt

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila, and Michael Geyer, eds. Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- Friedrich, Carl and Z. K. Brzezinski, Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy (Harvard University Press, 1st ed. 1956, 2nd ed. 1965).

- Gach, Nataliia. "From totalitarianism to democracy: Building learner autonomy in Ukrainian higher education." Issues in Educational Research 30.2 (2020): 532–554. online

- Gleason, Abbott. Totalitarianism: The Inner History Of The Cold War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), ISBN 0195050177.

- Gray, Phillip W. Totalitarianism: The Basics (New York: Routledge, 2023), ISBN 9781032183732.

- Gregor, A. Totalitarianism and political religion (Stanford University Press, 2020).

- Hanebrink, Paul. "European Protestants Between Anti-Communism and Anti-Totalitarianism: The Other Interwar Kulturkampf?" Journal of Contemporary History (July 2018) Vol. 53, Issue 3, pp. 622–643

- Hermet, Guy, with Pierre Hassner and Jacques Rupnik, Totalitarismes (Paris: Éditions Economica, 1984).

- Jainchill, Andrew, and Samuel Moyn. "French democracy between totalitarianism and solidarity: Pierre Rosanvallon and revisionist historiography." Journal of Modern History 76.1 (2004): 107–154. online

- Joscelyne, Sophie. "Norman Mailer and American Totalitarianism in the 1960s." Modern Intellectual History 19.1 (2022): 241–267 online.

- Keller, Marcello Sorce. "Why is Music so Ideological, Why Do Totalitarian States Take It So Seriously", Journal of Musicological Research, XXVI (2007), no. 2–3, pp. 91–122.

- Kirkpatrick, Jeane, Dictatorships and Double Standards: Rationalism and reason in politics (London: Simon & Schuster, 1982).

- ISBN 002034080X.

- Menze, Ernest, ed. Totalitarianism reconsidered (1981) online essays by experts

- Omnipotent Government: The Rise of the Total State and Total War(Yale University Press, 1944).

- Murray, Ewan. Shut Up: Tale of Totalitarianism (2005).

- Nicholls, A.J. "Historians and Totalitarianism: The Impact of German Unification." Journal of Contemporary History 36.4 (2001): 653–661.

- Patrikeeff, Felix. "Stalinism, Totalitarian Society and the Politics of 'Perfect Control'", Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, (Summer 2003), Vol. 4 Issue 1, pp. 23–46.

- Payne, Stanley G., A History of Fascism (London: Routledge, 1996).

- Rak, Joanna, and Roman Bäcker. "Theory behind Russian Quest for Totalitarianism. Analysis of Discursive Swing in Putin's Speeches." Communist and Post-Communist Studies 53.1 (2020): 13–26 online.

- Roberts, David D. Totalitarianism (John Wiley & Sons, 2020).

- Rocker, Rudolf, Nationalism and Culture (Covici-Friede, 1937).

- Sartori, Giovanni, The Theory of Democracy Revisited (Chatham, N.J: Chatham House, 1987).

- Sauer, Wolfgang. "National Socialism: totalitarianism or fascism?" American Historical Review, Volume 73, Issue #2 (December 1967): 404–424. online.

- Saxonberg, Steven. Pre-modernity, totalitarianism and the non-banality of evil: A comparison of Germany, Spain, Sweden and France (Springer Nature, 2019).

- Schapiro, Leonard. Totalitarianism (London: The Pall Mall Press, 1972).

- Selinger, William. "The politics of Arendtian historiography: European federation and the origins of totalitarianism." Modern Intellectual History 13.2 (2016): 417–446.

- Skotheim, Robert Allen. Totalitarianism and American social thought (1971) online

- The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy(London: Seeker & Warburg, 1952).

- Traverso, Enzo, Le Totalitarisme : Le XXe siècle en débat (Paris: Poche, 2001).

- Tuori, Kaius. "Narratives and Normativity: Totalitarianism and Narrative Change in the European Legal Tradition after World War II." Law and History Review 37.2 (2019): 605–638 online.

- Žižek, Slavoj, Did Somebody Say Totalitarianism? (London: Verso, 2001). online