Traditional Tibetan medicine

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Traditional Tibetan medicine (

The Tibetan medical system is based upon

History

As Indian culture flooded Tibet in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, a number of Indian medical texts were also transmitted.[5] For example, the Ayurvedic Astāngahrdayasamhitā (Heart of Medicine Compendium attributed to Vagbhata) was translated into Tibetan by རིན་ཆེན་བཟང་པོ། (Rinchen Zangpo) (957–1055).[6] Tibet also absorbed the early Indian Abhidharma literature, for example the fifth-century Abhidharmakosasabhasyam by Vasubandhu, which expounds upon medical topics, such as fetal development.[7] A wide range of Indian Vajrayana tantras, containing practices based on medical anatomy, were subsequently absorbed into Tibet.[8][9]

It was the aboriginal Tibetan people's accumulative knowledge of their local plants and their various usages for benefiting people's health that were collected by སྟོན་པོ་གཤེན་རབ་མི་བོ་ཆེ། the

གཡུ་ཐོག་ཡོན་ཏན་མགོན་པོ། (

In the 18th century, the missionaries who arrived in Tibet gave a detailed introduction to Tibetan medicine in their travelogues, and in 1789 the British surgeon Robert Saunder published an article on the concocting process of Tibetan medicines.[12] In the 1850s, the Russian capital, Saint Petersburg, opened a clinic of Tibetan medicine and a specialized school of Tibetan medicine.[13][14] In 1898, a part of the Tibetan medical masterpiece Four Medical Classics, was translated into Russian.[15] In Poland, Tibetan medicine was practiced in the 1920s, and two presidents, Stanisław Wojciechowski and Ignacy Mościcki, were both treated with Tibetan medicine.[16] In 1969, the PADMA AG in Zurich, Switzerland, the first Western company specializing in the production and sale of Tibetan medicine was established.[17]

In September 1959, the Tibetan People's Government merged "Menzikang" (སྨན་རྩིས་ཁང་) and Chagpori College of Medicine and established the Lhasa Tibetan Hospital on this basis. In September 1961, at the congress of Tibetan doctors in Lhasa area, Chingpo Lobu was appointed as the director of Lhasa Tibetan Hospital. On September 1, 1980, the Tibet Autonomous Region expanded Lhasa Tibetan Hospital to become Tibetan Hospital of Tibet Autonomous Region (西藏自治区藏医院), laying a solid foundation for the vigorous development of Tibetan medicine.[18] In 1999, Tibet Nordicam Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. became the first high-tech pharmaceutical listed enterprise born in Tibet Autonomous Region.[19] In 2006, the first Tibetan medicine group in Tibet Autonomous Region was established in Lhasa, marking the establishment of a mature modern enterprise system in the Tibetan medicine industry. In 2023, Tibetan Hospital of Tibet Autonomous Region became the National Center for Traditional Chinese Medicine (Tibetan Medicine) preparatory units.[20]

Four Tantras

The Four Tantras (Gyuzhi, རྒྱུད་བཞི།) is a native Tibetan text incorporating Indian, Greco-Arab, and

- Root Tantra – A general outline of the principles of Tibetan medicine, it discusses the humors in the body and their imbalances and their link to illness. The Four Tantra uses visual observation to diagnose predominantly the analysis of the pulse, tongue and analysis of the urine (in modern terms known as urinalysis )[25]

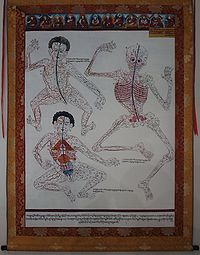

- Exegetical Tantra – This section discusses in greater detail the theory behind the Four Tantras and gives general theory on subjects such as anatomy, physiology, psychopathology, embryology and treatment.[26]

- Instructional Tantra – The longest of the Tantras is mainly a practical application of treatment, it explains in detail illnesses and which humoral imbalance which causes the illness. This section also describes their specific treatments.

- Subsequent Tantra – Diagnosis and therapies, including the preparation of Tibetan medicine and cleansing of the body internally and externally with the use of techniques such as moxibustion, massage and minor surgeries.[27]

Three principles of function

Like other systems of traditional Asian medicine, and in contrast to

• rLung[28] is the source of the body's ability to circulate physical substances (e.g. blood), energy (e.g. nervous system impulses), and the non-physical (e.g. thoughts). In embryological development, the mind's expression of materialism is manifested as the system of rLung. There are five distinct subcategories of rLung each with specific locations and functions: Srog-'Dzin rLüng, Gyen-rGyu rLung, Khyab-Byed rLüng, Me-mNyam rLung, Thur-Sel rLüng.

• mKhris-pa[28] is characterized by the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of heat, and is the source of many functions such as thermoregulation, metabolism, liver function and discriminating intellect. In embryological development, the mind's expression of aggression is manifested as the system of mKhris-pa. There are five distinct subcategories of mKhris-pa each with specific locations and functions: 'Ju-Byed mKhris-pa, sGrub-Byed mKhris-pa, mDangs-sGyur mKhris-pa, mThong-Byed mKhris-pa, mDog-Sel mKhris-pa.

• Bad-kan[28] is characterized by the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of cold, and is the source of many functions such as aspects of digestion, the maintenance of our physical structure, joint health and mental stability. In embryological development, the mind's expression of ignorance is manifested as the system of Bad-kan. There are five distinct subcategories of Bad-kan each with specific locations and functions: rTen-Byed Bad-kan, Myag-byed Bad-kan, Myong-Byed Bad-kan, Tsim-Byed Bad-kan, 'Byor-Byed Bad-kan.

Usage

A key objective of the

The Government of India has approved the establishment of the National Institute for Sowa-Rigpa (NISR) in

Notable practitioners

See also

References

- ^ Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. pp. 23–32.

- ^ ISBN 978-0764917615.

- ^ Kala, C.P. (2005) Health traditions of Buddhist community and role of amchis in trans-Himalayan region of India. Current Science, 89 (8): 1331-1338.

- S2CID 256618310.

- ^ Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. p. 23.

- ^ Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. p. 24.

- ^ Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. pp. 26–27.

- ^ Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. p. 31.

- ^ Kala, C.P. (2002) Medicinal Plants of Indian Trans-Himalaya: Focus on Tibetan Use of Medicinal Resources. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehradun, India. 200 pp.

- ^ Phuntsok, Thubten. "བོད་ཀྱི་ལོ་རྒྱུས་སྤྱི་དོན་པདྨ་རཱ་གའི་ལྡེ་མིག "A General History of Tibet"". HimalayaBon.

- ^ William, McGrath (2017). "Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition". UVA Library | Virgo. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- ^ Saunders, Robert (1789). Some Account of the Vegetable and Mineral Productions of Boutan and Thibet. Royal Society of London. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-253-00184-9. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ISBN 978-0-691-18271-1. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ISBN 978-7-81009-825-0. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ISBN 978-0-295-80708-9. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ISBN 978-90-04-40444-1. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ^ "《四部医典》:流传千年的藏医药经典著作". www.zgdazxw.com.cn. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ISBN 978-7-5097-5473-3. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ^ "西藏自治区藏医院挂牌成为国家中医医学中心(藏医)筹建单位-中新网". www.chinanews.com.cn. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Bynum, W.F. Dictionary of Medical Biography. London: Greenwood Press. p. 1343.

- ^ Alphen, Jon Van. Oriental Medicine- An illustrated Guide to the Asian Arts of Healing. London: Serindia Publications. p. 114.

- ISBN 978-1-61180-359-4. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ISBN 978-90-04-40444-1. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ISBN 978-81-86419-62-5. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ISBN 978-81-208-1567-4. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ISBN 978-0-295-80708-9. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ^ ISBN 81-86419-62-4

- ISBN 978-7-5097-5473-3. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ^ "藏医藏药:从传统走向现代化". news.sina.com.cn. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Cabinet approves establishment of National Institute for Sowa-Rigpa in Leh". www.newsonair.com. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

Further reading

This article contains a list that has not been properly sorted. Specifically, it does not follow the MOS:LISTSORT for more information. if you can. (March 2024) |

- Avedon, John F. (1981-01-11). "Exploring the Mysteries of Tibetan Medicine". The New York Times.

- Analysis of Five Pharmacologically Active Compounds from the Tibetan Medicine Elsholtzia with Micellar Electrokinetic Capillary Chromatography. Chenxu Ding; Lingyun Wang; Xianen Zhao; Yulin Li; Honglun Wang; Jinmao You; Yourui Suo | Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies | 200730:20, | 3069(15) | ISSN 1082-6076

- HPLC‐APCI‐MS Determination of Free Fatty Acids in Tibet Folk Medicine Lomatogonium rotatum with Fluorescence Detection and Mass Spectrometric Identification. Yulin Li; Xian'en Zhao; Chenxu Ding; Honglun Wang; Yourui Suo; Guichen Chen; Jinmao You | Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies | 200629:18, | 2741(11) | ISSN 1082-6076

- Stack, Peter. "The Spiritual Logic Of Tibetan Healing.(Review)." San Francisco Chronicle. (Feb 20, 1998)

- Dunkenberger, Thomas / "Tibetan Healing Handbook" / Lotus Press - Shangri-La, Twin Lakes, WI / 2000 / ISBN 0-914955-66-7

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (March 2024) |

- The first Tibetan medicine school established in the West.

- Tibetan Medical & Astro-science Institute

- Tibetanmedicine.com

- Central Council of Tibetan Medicine

- Tibet Center Institute - official Cooperation partner of Men-Tsee-Khang for the Education in Traditional Tibetan Medicine

- Academy for Traditional Tibetan Medicine

- Tibetan medicine and astrology