Trans-Saharan slave trade

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

The Trans-Saharan slave trade, also known as the Arab slave trade,

Early trans-Saharan slave trade

Records of slave trading and transportation in the Sahara date back as far as the 3rd millennium BC during the reign of the Egyptian king Sneferu who crossed the fourth cataract of the Nile into what is today modern Sudan to capture slaves and send them north.[10] These raids for prisoners of war, who subsequently became slaves, were a regular occurrence in the ancient Nile Valley and Africa. During times of conquest and after winning battles, the ancient Nubians were taken as slaves by the ancient Egyptians.[11]

The

In the early

Trans-Saharan slave trade in the Middle Ages

Aside from raiding, slaves could also be obtained by purchasing them from local black rulers. The 9th century Arab historian Ya'qubi states:

They [the Arabs] export black slaves...belonging to the Mira, Zaghawa, Maruwa, and other black races who are near to them and whom they capture. I hear that the black kings sell blacks, without pretext and without war.[21]

Indeed, few African rulers would resist the slave trade, while many chiefs would become middlemen in the trafficking, rounding up members of nearby villages to be sold to visiting merchants.[22] The 12th century Arab geographer al-Idrisi noted that black Africans would also participate in slave raiding stating that:

The people of Lemlem are perpetually being invaded by their neighbors, who take them as slaves... and carry them off to their own lands to sell them by the dozens to the merchants. Every year great numbers of them are sent off to the Western Maghreb.[21]

Al-Idrisi would also describe the different methods Muslim merchants would use to enslave blacks, recording that some would "steal the children of the Zanj using

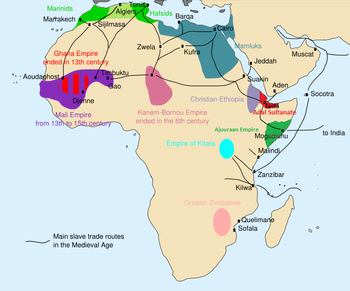

The routes taken by slave caravans transporting slaves depended on their destination. Slaves headed to Egypt would be carried by boat down the Nile and slaves headed to Arabia would be sent to ports on the

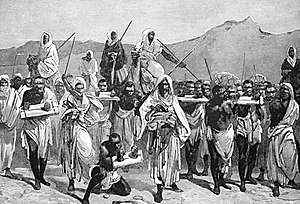

Passage through the Sahara required the expertise of ethnic groups whose lifestyles were uniquely adapted for survival in scorching, arid environments, namely the local Berber tribes and the foreign

The goods exchanged in the Trans-Saharan slave trade varied. In the 10th century, the Muslim scholar Mutahhar ibn Tahir al-Maqdisi described the trade between the Islamic world and Africa as consisting of food and clothing being imported into Africa while slaves, gold, and coconuts were exported out of Africa.[19] Later, the 16th century Andalusian writer Leo Africanus wrote that traders from Morocco would bring horses, European cloth, clothing, sugar, books, and brass vessels to Sudan in order to exchange them for slaves, civets and gold.[27] According to Africanus, the sultan of Bornu would accept payment for slaves only in horses, with an exchange rate of up to one slave per twenty horses.[27]

The range of tasks given to slaves was varied and included servile labor utilized for "

In some instances, Christians in Africa would acquiesce to Muslims demands that they be provided with slaves. In 641 AD during the treaty known as the Baqt was signed establishing an agreement between the Nubian Christian state of Makuria and the new Muslim rulers of Egypt, in which the Nubians agreed to give Muslim traders more privileges of trade in addition to sending 442 slaves every year to Cairo as tribute.[17][34] This treaty remained intact for 600 years all while the slave trade within Nubia continued unimpeded.[17]

In the

In 1416, al-Maqrizi told how pilgrims coming from

Arabs were sometimes made into slaves in the trans-Saharan slave trade.[38][39] In Mecca, Arab women were sold as slaves according to Ibn Butlan, and certain rulers in West Africa had slave girls of Arab origin.[40][41] According to al-Maqrizi, slave girls with lighter skin were sold to West Africans on hajj.[42][43][44] Ibn Battuta met an Arab slave girl near Timbuktu in Mali in 1353. Battuta wrote that the slave girl was fluent in Arabic, from Damascus, and her master's name was Farbá Sulaymán.[45][46][47] Besides his Damascus slave girl and a secretary fluent in Arabic, Arabic was also understood by Farbá himself.[48] The West African states also imported highly trained slave soldiers.[49]

Under the

Late trans-Saharan slave trade

In Central Africa during the 16th and 17th centuries, slave traders continued to raid the region as part of the expansion of the Saharan and Nile River slave routes. It is estimated that, in the 17th and 18th centuries, 1.4 million slaves were forced to make the trek through the Sahara [5] Captives were enslaved and shipped to the Mediterranean coast, Europe, Arabia, the Western Hemisphere, or to the slave ports and factories along the West and North Africa coasts or South along the Ubanqui and Congo rivers.[52][53]

1.2 million slaves are estimated to have been sent through the Sahara in the 19th century.[5] In the 1830s, a period when slave trade flourished, Ghadames was handling 2,500 slaves a year.[54] Even though the slave trade was officially abolished in Tripoli in 1853, in practice it continued until the 1890s.[55] One witness to the behavior of the slave dealers, G.F. Lyon, described their behavior in Libya:

None of the owners were ever without their whips which were in constant use...no slave dares to be ill or unable to walk, but when the poor sufferer dies the master suspects there must have been "something wrong inside" and regrets not having liberally applied the usual remedy of burning the belly with a red hot iron" thus reconciling to themselves their cruel treatment of these unfortunate creatures.[56]

In Tripoli, Lyon recorded that from 4,000 to 5,000 slaves were processed annually with raids to areas like Kanem-Bornu providing sources of captives.[25]

Other 19th-century European explorers recorded their perilous experiences traveling through the Saharan Desert alongside slave caravans. The explorer Gustav Nachtigal reported finding numerous bones at desert springs that had run dry.[26] Nachtigal estimated that for every one slave that successfully arrived at the market three or four had either died or escaped.[26] Cold could also kill in the desert as the explorer Heinrich Barth relayed a story that the vizier of Bornu had lost forty slaves in a single night in Libya.[26] A British account described one hundred skeletons.[26]

By 1858, the British consul in Tripoli had recorded that more than 66% of the value shipped across the Sahara was made up by slaves.

Adolf Vischer wrote in an article published in 1911 that: "...it has been said that slave traffic is still going on on the Benghazi-

Abolition

After the establishment of the

Slavery in the post-Gaddafi Libya

Since the beginning of the

After receiving unverified CNN video of a November 2017 slave auction in Libya, a human trafficker told

A Libyan group known as the Asma Boys have antagonized migrants from other parts of Africa from at least as early as 2000, destroying their property.[71] Nigerian migrants in January 2018 gave accounts of abuses in detention centres, including being leased or sold as slaves.[72] Videos of Sudanese migrants being burnt and whipped for ransom, were released later on by their families on social media.[73] In June 2018, the United Nations applied sanctions against four Libyans (including a Coast Guard commander) and two Eritreans for their criminal leadership of slave trade networks.[74]

Routes

According to professor Ibrahima Baba Kaké, there were four main slavery routes to North Africa, from east to west of Africa, from the Maghreb to the Sudan, from Tripolitania to central Sudan and from Egypt to the Middle East.[75] Caravan trails, set up in the 9th century, went past the oasis of the Sahara; travel was difficult and uncomfortable. Since Roman times, long convoys had transported slaves.

See also

- Baqt

- Barbary slave trade

- Comoros slave trade

- Haratin

- Indian Ocean slave trade

- Red Sea slave trade

- Zanzibar slave trade

- Trans-Sahara Highway

- Trans-Saharan trade

- Slavery in ancient Egypt

- Slavery in ancient Rome

- Slavery in Africa

- Human trafficking in Chad

- Slavery in Libya

- Slavery in Mali

- Slavery in Mauritania

- Slavery in Niger

- Slavery in Nigeria

References

- ISBN 978-3-031-19631-7.

Trans-Saharan slave trade was conducted within the ambits of the trans-Saharan trade, otherwise referred to as the Arab trade. Trans-Saharan trade, conducted across the Sahara Desert, was a web of commercial interactions between the Arab world (North Africa and the Persian Gulf) and sub-Saharan Africa.

- .

Africans experienced three distinct types of slave trades: (1) The European Slave Trade that took Africans across the Atlantic from the mid-fifteenth century until the end of the nineteenth century; (2) the Arab Slave Trade across the Sahara and the Indian Ocean that predated European contact with Africa; and (3) domestic slavery.

- JSTOR 26500685.

In West Africa, the Arab slave trade encompassed a vast region from the Niger valley to the Gulf of Guinea. This traffic followed the trans-Saharan roads.

- ^ a b c Bradley, Keith R. "Apuleius and the sub-Saharan slave trade". Apuleius and Antonine Rome: Historical Essays. p. 177.

- ^ a b c Segal 2001, p. 55-57.

- ^ OCLC 1045855145.

- ISBN 978-90-474-4003-1.

While the Europeans organized the West African slave trade, the Arabs managed the East African and trans-Saharan counterparts.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-8470-0.

- ^ a b Akinbode, Ayomide (20 December 2021). "The Forgotten Arab Slave Trade of East Africa". The History Ville. Archived from the original on 6 December 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- OCLC 1120917849.

- ^ Redford, D. B..From Slave to Pharaoh: The Black Experience of Ancient Egypt. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. Project MUSE

- ^ "Fall of Gaddafi opens a new era for the Sahara's lost civilisation". the Guardian. 5 November 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ David Mattingly. "The Garamantes and the Origins of Saharan Trade". Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–28.

- ^ Austen, R. (2015). Regional study: Trans-Saharan trade. In C. Benjamin (Ed.), The Cambridge World History (The Cambridge World History, pp. 662-686). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139059251.026

- ^ a b c d e Wilson, Andrew. "Saharan Exports to the Roman World". Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. pp. 192–3.

- ^ OCLC 1014163824.

- ^ a b c d e f Gordon 1989, p. 108-110.

- ^ a b c d e f Gordon 1989, p. 114-115.

- ^ OCLC 1022745387.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 2-5.

- ^ a b Gordon 1989, p. 122.

- ^ Gordon 1989, p. 107.

- ^ "Ibn Battuta's Trip: Part Twelve – Journey to West Africa (1351-1353)". Archived from the original on 9 June 2010.

- ^ Noel King (ed.), Ibn Battuta in Black Africa, Princeton 2005, p. 54.

- ^ a b Segal 2001, p. 131-132.

- ^ a b c d e f Segal 2001, p. 63-65.

- ^ a b c Gordon 1989, p. 111-113.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 3-5.

- ^ a b Segal 2001, p. 40-43.

- ^ a b c d e f Lewis 1992, p. 56-57.

- ^ OCLC 1025724912.

- ^ Segal 2001, p. 141-143.

- ^ "The impact of the slave trade on Africa". April 1998.

- ^ Jay Spaulding. "Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World: A Reconsideration of the Baqt Treaty," International Journal of African Historical Studies XXVIII, 3 (1995)

- ^ a b c d e Lewis 1992, p. 58.

- ^ Lewis 1992, p. 53.

- OCLC 1013305190.

- ^ Muhammad A. J. Beg, The "serfs" of Islamic society under the Abbasid regime, Islamic Culture, 49, 2, 1975, p. 108

- ISBN 9780195826913.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 70.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-2716-4.

- ISBN 978-1-139-62004-8.

- ISBN 978-0-86356-764-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-1825-1.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-336-4.

- ISBN 978-0-415-34473-9.

- ^ Raymond Aaron Silverman (1983). History, art and assimilation: the impact of Islam on Akan material culture. University of Washington. p. 51.

- ISBN 9780060647094.

- ^ Ralph A. Austen. Trans-Saharan Africa in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 31.

- ^ a b Cornwell, Graham Hough (2018). Sweetening the Pot: A History of Tea and Sugar in Morocco, 1850-1960 (thesis thesis). Georgetown University.

- ^ "DARB EL ARBA'IN. THE FORTY DAYS' ROAD | W. B. K. Shaw | download". ur.booksc.me. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- )

- ^ Alistair Boddy-Evans. Central Africa Republic Timeline – Part 1: From Prehistory to Independence (13 August 1960), A Chronology of Key Events in Central Africa Republic Archived 23 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. About.com

- ^ K. S. McLachlan, "Tripoli and Tripolitania: Conflict and Cohesion during the Period of the Barbary Corsairs (1551-1850)", Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 3, No. 3, Settlement and Conflict in the Mediterranean World. (1978), pp. 285-294.

- ^ a b Lisa Anderson, "Nineteenth-Century Reform in Ottoman Libya", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 16, No. 3. (Aug., 1984), pp. 325-348.

- ^ Segal 2001, p. 136.

- ^ Adolf Vischer, "Tripoli", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 38, No. 5. (Nov., 1911), pp. 487-494.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-38046-1.

- ISBN 1-85065-050-0.

- ^ (in French) Raëd Bader, Noirs en Algérie, XIXe-XXe siècles, éd. École normale supérieure de Lyon, 20 June 2006

- ^ "Le Petit Parisien. Supplément littéraire illustré". Gallica. 2 June 1907. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ OCLC 823724244.

- ^ a b African migrants sold in Libya 'slave markets', IOM says. 11 April 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Migrants from west Africa being 'sold in Libyan slave markets'". The Guardian.

- ^ "African migrants sold as 'slaves' in Libya". 3 July 2020.

- ^ "West African migrants are kidnapped and sold in Libyan slave markets / Boing Boing". boingboing.net. 11 April 2017.

- ^ Adams, Paul (28 February 2017). "Libya exposed as child migrant abuse hub". BBC News.

- ^ "Immigrant Women, Children Raped, killed and Starved in Libya's Hellholes: Unicef". 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ "African refugees bought, sold and murdered in Libya". Al-Jazeera.

- ^ "Exclusive: Italian doctor laments Libya's 'concentration camps' for migrants". Euronews. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Africa Research Bulletin: Economic, financial, and technical series, Volume 37. Blackwell. 2000. p. 14496. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "'Used as a slave' in a Libyan detention centre". BBC News. 2 January 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Elbagir, Nima; Razek, Raja; Sirgany, Sarah; Tawfeeq, Mohammed (25 January 2018). "Migrants beaten and burned for ransom". CNN. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Elbagir, Nima; Said-Moorhouse, Laura (7 June 2018). "Unprecedented UN sanctions slapped on 'millionaire migrant traffickers'". CNN. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ISBN 978-1571812650. Retrieved 26 May 2015.