Transcranial magnetic stimulation

| Transcranial magnetic stimulation | |

|---|---|

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (schematic diagram) | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

| MeSH | D050781 |

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive form of

TMS has shown diagnostic and therapeutic potential in the central nervous system with a wide variety of disease states in neurology and mental health, with research still evolving.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

Adverse effects of TMS appear rare and include

Medical uses

TMS does not require surgery or electrode implantation.

Its use can be diagnostic and/or therapeutic. Effects vary based on frequency and intensity of the magnetic pulses as well as the length of treatment, which dictates the total number of pulses given.[14] TMS treatments are approved by the FDA in the US and by NICE in the UK for the treatment of depression and are predominantly provided by private clinics. TMS stimulates cortical tissue without the pain sensations produced in transcranial electrical stimulation.[15]

Diagnosis

TMS can be used clinically to measure activity and function of specific brain circuits in humans, most commonly with single or paired magnetic pulses.

Treatment

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

Repetitive high frequency TMS (rTMS) has been investigated as a possible treatment option with various degrees of success in conditions including[19][20]

- Chronic neuropathic pain

- Motor diseases (e.g., Parkinson's disease, essential tremor)

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Epilepsy

- Disorders of consciousness (e.g., vegetative state or minimally conscious state)

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Psychiatric diseases, such as depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety and Tourette syndrome

Adverse effects

Although TMS is generally regarded as safe, risks are increased for therapeutic rTMS compared to single or paired diagnostic TMS.[21] Adverse effects generally increase with higher frequency stimulation.[12]

The greatest immediate risk from TMS is

Procedure

During the procedure, a magnetic coil is positioned at the head of the person receiving the treatment using anatomical landmarks on the skull, in particular the inion and nasion.[13] The coil is then connected to a pulse generator, or stimulator, that delivers electric current to the coil.[2]

Physics

TMS uses

The magnetic field is about the same strength as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the pulse generally reaches no more than 5 centimeters into the brain unless using a modified coil and technique for deeper stimulation.[25]

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is achieved by quickly discharging current from a large

TMS usually stimulates to a depth from 2 to 4 cm below the surface, depending on the coil and intensity used. Consequently, only superficial brain areas can be affected.

Frequency and duration

The effects of TMS can be divided based on frequency, duration and intensity (amplitude) of stimulation:[30]

- Single or paired pulse TMS causes neurons in the neocortex under the site of stimulation to occipital cortex, 'phosphenes' (flashes of light) might be perceived by the subject. In most other areas of the cortex, there is no conscious effect, but behaviour may be altered (e.g., slower reaction time on a cognitive task), or changes in brain activity may be detected using diagnostic equipment.[31]

- Repetitive TMS produces longer-lasting effects which persist past the period of stimulation. rTMS can increase or decrease the excitability of the corticospinal tract depending on the intensity of stimulation, coil orientation, and frequency. Low frequency rTMS with a stimulus frequency less than 1 Hz is believed to inhibit cortical firing while a stimulus frequency greater than 1 Hz, or high frequency, is believed to provoke it.[32] Though its mechanism is not clear, it has been suggested as being due to a change in synaptic efficacy related to long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression like plasticity (LTD-like plasticity).[33][34]

Coil types

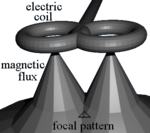

Most devices use a coil shaped like a figure-eight to deliver a shallow magnetic field that affects more superficial neurons in the brain.[9] Differences in magnetic coil design are considered when comparing results, with important elements including the type of material, geometry and specific characteristics of the associated magnetic pulse.

The core material may be either a magnetically inert substrate ('air core'), or a solid,

A number of different types of coils exist, each of which produce different magnetic fields. The round coil is the original used in TMS. Later, the figure-eight (butterfly) coil was developed to provide a more focal pattern of activation in the brain, and the four-leaf coil for focal stimulation of peripheral nerves. The double-cone coil conforms more to the shape of the head.[36] The Hesed (H-core), circular crown and double cone coils allow more widespread activation and a deeper magnetic penetration. They are supposed to impact deeper areas in the motor cortex and cerebellum controlling the legs and pelvic floor, for example, though the increased depth comes at the cost of a less focused magnetic pulse.[12]

History

Work to directly stimulate the human brain with electricity started in the late 1800s, and by the 1930s the Italian physicians

In 1980 Merton and Morton successfully used transcranial electrical stimulation (TES) to stimulate the motor cortex. However, this process was very uncomfortable, and subsequently Anthony T. Barker began to search for an alternative to TES.[39] He began exploring the use of magnetic fields to alter electrical signaling within the brain, and the first stable TMS devices were developed in 1985.[37][38] They were originally intended as diagnostic and research devices, with evaluation of their therapeutic potential being a later development.[37][38] The United States' FDA first approved TMS devices in October 2008.[37]

Research

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

TMS has shown potential therapeutic effect on

With Parkinson's disease, early results suggest that low frequency stimulation may have an effect on medication associated dyskinesia, and that high frequency stimulation improves motor function.[46][47] The most effective treatment protocols appear to involve high frequency stimulation of the motor cortex, particularly on the dominant side,[48] but with more variable results for treatment of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.[49] It is less effective than electroconvulsive therapy for motor symptoms, though both appear to have utility.[50][51][52] Cerebellar stimulation has also shown potential for the treatment of levodopa associated dyskinesia.[53]

In

TMS can also be used to map functional connectivity between the cerebellum and other areas of the brain.[61]

A study on alternative Alzheimer's treatments at the Wahrendorff Clinic in Germany in 2021[62] reported that 84% of participants in the study have experienced positive effects after using the treatment.

Under the supervision of Professor Marc Ziegenbein, a psychiatry and psychotherapy specialist, the study of 77 subjects with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease received frequent transcranial magnetic stimulation applications and observed over a period of time.

Improvements were mainly found in the areas of orientation in the environment, concentration, general well-being and satisfaction.

Study blinding

Mimicking the physical discomfort of TMS with

A 2011 review found that most studies did not report

Animal model limitations

TMS research in animal studies is limited due to its early US Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment-resistant depression, limiting development of animal specific magnetic coils.[68]

Treatments for the general public

Regulatory approvals

Neurosurgery planning

Nexstim obtained United States Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act§Section 510(k) clearance for the assessment of the primary motor cortex for pre-procedural planning in December 2009[69] and for neurosurgical planning in June 2011.[70]

Depression

The National Institutes of Health estimates depression medications work for 60 percent to 70 percent of people who take them.[71][72] TMS is approved as a Class II medical device under the "de novo pathway".[73][74] In addition, the World Health Organization reports that the number of people living with depression has increased nearly 20 percent since 2005.[75] In a 2012 study, TMS was found to improve depression significantly in 58 percent of patients and provide complete remission of symptoms in 37 percent of patients.[76] In 2002, Cochrane Library reviewed randomized controlled trials using TMS to treat depression. The review did not find a difference between rTMS and sham TMS, except for a period 2 weeks after treatment.[77] In 2018, Cochrane Library stated a plan to contact authors about updating the review of rTMS for depression.[78]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)

In August 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) authorized the use of TMS developed by the Israeli company Brainsway in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[79]

In 2020, US FDA authorized the use of TMS developed by the U.S. company MagVenture Inc. in the treatment of OCD.[80]

In 2023, US FDA authorized the use of TMS developed by the U.S. company Neuronetics Inc. in the treatment of OCD.[81]

Other neurological areas

In the European Economic Area, various versions of Deep TMS H-coils have CE marking for Alzheimer's disease,[82]

Coverage by health services and insurers

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom's

NICE evaluated TMS for severe depression (IPG 242) in 2007, and subsequently considered TMS for reassessment in January 2011 but did not change its evaluation.[89] The Institute found that TMS is safe, but there is insufficient evidence for its efficacy.[89]

In January 2014, NICE reported the results of an evaluation of TMS for treating and preventing migraine (IPG 477). NICE found that short-term TMS is safe but there is insufficient evidence to evaluate safety for long-term and frequent uses. It found that evidence on the efficacy of TMS for the treatment of migraine is limited in quantity, that evidence for the prevention of migraine is limited in both quality and quantity.[90]

Subsequently, in 2015, NICE approved the use of TMS for the treatment of depression in the UK and IPG542 replaced IPG242.[91] NICE said "The evidence on repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression shows no major safety concerns. The evidence on its efficacy in the short-term is adequate, although the clinical response is variable. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression may be used with normal arrangements for clinical governance and audit."

United States: commercial health insurance

In 2013, several commercial health insurance plans in the United States, including

United States: Medicare

Policies for Medicare coverage vary among local jurisdictions within the Medicare system,[100] and Medicare coverage for TMS has varied among jurisdictions and with time. For example:

- In early 2012 in New England, Medicare covered TMS for the first time in the United States.[101][102][103][104] However, that jurisdiction later decided to end coverage after October, 2013.[105]

- In August 2012, the jurisdiction covering Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico determined that there was insufficient evidence to cover the treatment,[106] but the same jurisdiction subsequently determined that Medicare would cover TMS for the treatment of depression after December 2013.[107]

- Subsequently,[when?] some other Medicare jurisdictions added Medicare coverage for depression.[citation needed]

See also

- Cortical stimulation mapping

- Cranial electrotherapy stimulation

- Electrical brain stimulation

- Electroconvulsive therapy

- Low field magnetic stimulation

- My Beautiful Broken Brain

- Non-invasive cerebellar stimulation

- Transcranial alternating current stimulation

- Transcranial direct-current stimulation

- Transcranial random noise stimulation

- Vagus nerve stimulation

References

- ^ NICE. January 2014 Transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating and preventing migraine

- ^ a b Michael Craig Miller for Harvard Health Publications. July 26, 2012 Magnetic stimulation: a new approach to treating depression?

- ^ PMID 22349304.

- ^ S2CID 206798663.

- ^ PMID 21474597.

- PMID 22091472.

- ^ PMID 23249815.

- ^ a b Perera, Tarique; George, Mark; Grammer, Geoffrey; Janicak, Philip; Pascual-Leone, Alvaro; Wirecki, Theodore (April 27, 2015). TMS Therapy For Major Depressive Disorder: Evidence Review and Treatment Recommendations for Clinical Practice (PDF) (Report).

- ^ S2CID 29053871.

- ^ PMID 26289586.

- ^ "Pupil response may shed light on who responds best to transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression". www.uclahealth.org. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- ^ S2CID 225049093.

- ^ S2CID 25100990.

- PMID 26319963.

- ISBN 9780444640321. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- S2CID 19629888.

- ^ PMID 19767591.

- ^ PMID 20714076.

- ^ .

- ISSN 1388-2457.

- PMID 25504707.

- PMID 26664122.

- ISBN 978-3-642-36466-2.

- PMID 28264713.

- ^ a b "Brain Stimulation Therapies". NIMH.

- ISBN 978-0-521-84471-0.

- ^ a b V. Walsh and A. Pascual-Leone, "Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Neurochronometrics of Mind." Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2003.

- .

- ^ See:

- Zangen A, Roth Y, Voller B, Hallett M (April 2005). "Transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions: evidence for efficacy of the H-coil". Clinical Neurophysiology. 116 (4): 775–779. S2CID 25101101.

- Huang YZ, Sommer M, Thickbroom G, Hamada M, Pascual-Leonne A, Paulus W, et al. (January 2009). "Consensus: New methodologies for brain stimulation". Brain Stimulation. 2 (1): 2–13. PMID 20633398.

- Zangen A, Roth Y, Voller B, Hallett M (April 2005). "Transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions: evidence for efficacy of the H-coil". Clinical Neurophysiology. 116 (4): 775–779.

- PMID 22072509.

- ISBN 978-0-340-72009-7.

- PMID 22901565.

- S2CID 31458874.

- ^ Baur D, Galevska D, Hussain S, Cohen LG, Ziemann U, Zrenner C. Induction of LTD-like corticospinal plasticity by low-frequency rTMS depends on pre-stimulus phase of sensorimotor μ-rhythm. Brain Stimul. 2020 Nov-Dec;13(6):1580-1587. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.09.005. Epub 2020 Sep 17. PMID 32949780; PMCID: PMC7710977.

- ISBN 978-0-19-856892-6.

- PMID 7511524.

- ^ S2CID 13262044.

- ^ PMID 27057180.

- PMID 26319963.

- PMID 23728676.

- S2CID 3880211.

- PMID 19818232.

- S2CID 16233265.

- PMID 19205161.

- PMID 25170668.

- PMID 19152730.

- PMID 37773851.

- ^ PMID 25686212.

- PMID 30264518.

- PMID 16291882.

- S2CID 6404434.

- PMID 18471317.

- S2CID 46810543.

- PMID 25230088.

- PMID 23615189.

- S2CID 22071333.

- PMID 26536383.

- PMID 22846200. Archived from the originalon 2014-02-26.

- PMID 34589245.

- PMID 31014413.

- S2CID 3999098.

- ^ "Alternative Alzheimer's Treatments Offering Hope - 84% of the subjects surveyed rated their psychological well-being after the TPS treatment as medium to good". Hitoshin. 11 April 2023.

- PMID 25767458.

- S2CID 2152097.

- S2CID 38081703.

- PMID 19293925.

- S2CID 21439740.

- PMID 21924290.

- ^ "FDA clears Nexstim´s Navigated Brain Stimulation for non-invasive cortical mapping prior to neurosurgery – Archive – Press Releases". nexstim.com.

- ^ "Nexstim Announces FDA Clearance for NexSpeech® – Enabling Noninvasive Speech Mapping Prior to Neurosurgery". businesswire.com. 11 June 2012.

- ^ Information about Mental Illness and the Brain. National Institutes of Health (US). 2007.

- ^ In addition, the World Health Organization reports that the number of people living with depression has increased nearly 20 percent since 2005.

- ^ Michael Drues, for Med Device Online. 5 February 2014 Secrets Of The De Novo Pathway, Part 1: Why Aren't More Device Makers Using It?

- PMID 26177612.

- ^ ""Depression: let's talk" says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- S2CID 22968810.

- PMID 12076483. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- PMID 12076483.

- ^ "FDA permits marketing of transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder". Food and Drug Administration. 2020-02-20.

- ^ "MagVenture receives FDA clearance for OCD | Clinical TMS Society". www.clinicaltmssociety.org. Retrieved 2023-10-11.

- ^ "FDA clears OCD motor threshold cap for transcranial magnetic stimulation system". www.healio.com. Retrieved 2023-10-11.

- ^ a b c "Brainsway reports positive Deep TMS system trial data for OCD". Medical Device Network. Medicaldevice-network. September 6, 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Brainsway's Deep TMS EU Cleared for Neuropathic Chronic Pain". medGadget. July 3, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- PMID 27114902.

- PMID 26579065.

- PMID 34733479.

- PMID 23770409.

- ^ NICE About NICE: What we do

- ^ a b "Transcranial magnetic stimulation for severe depression (IPG242)". London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2011-03-04.

- ^ "Transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating and preventing migraine". London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. January 2014.

- ^ "Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 16 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "Medical Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Depression and Other Neuropsychiatric Disorders". Policy No. BEH.00002. Anthem, Inc. 2013-04-16. Archived from the original on 2013-07-29. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ^ Health Net (March 2012). "National Medical Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation" (PDF). Policy Number NMP 508. Health Net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- ^ "Medical Policy Manual" (PDF). Section IV.67. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska. 2011-05-18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-28.

- ^ "Medical Coverage Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Treatment of Depression and Other Psychiatric/Neurologic Disorders" (PDF). Blue Cross Blue Shield of Rhode Island. 2012-05-15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-26. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- UnitedHealthcare (2013-12-01). "Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation" (PDF). UnitedHealthCare. p. 2. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2013-05-20. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ^ Aetna (2013-10-11). "Clinical Policy Bulletin: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Cranial Electrical Stimulation". Number 0469. Aetna. Archived from the original on 2013-10-22. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ^ Cigna (2013-01-15). "Cigna Medical Coverage Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation" (PDF). Coverage Policy Number 0383. Cigna. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-04. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- Regence (2013-06-01). "Medical Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation as a Treatment of Depression and Other Disorders" (PDF). Policy No. 17. Regence. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2014-12-09. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2013-07-10. Archived from the originalon 2014-02-14. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the originalon 2014-02-17. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ^ "Important Treatment Option for Depression Receives Medicare Coverage". Press Release. PBN.com: Providence Business News. 2012-03-30. Archived from the original on 2013-04-05. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- ^ The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (June 2012). "Coverage Policy Analysis: Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)" (PDF). The New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council (CEPAC). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ^ "Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Cites Influence of New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council (CEPAC)". Berlin, Vermont: Central Vermont Medical Center. 2012-02-06. Archived from the original on 2012-03-25. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2014-02-17.