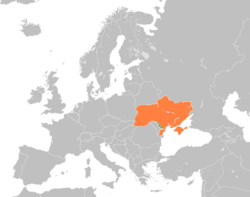

Transnistria–Ukraine relations

| |

Transnistria |

Ukraine |

|---|---|

Transnistria–Ukraine relations is the bilateral relationship between the

History

In 1924, the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was formed. Until 1940, the territory which in the present is Transnistria was part of the Ukrainian SSR.

Economy

The most influential Transnistrian company is Sheriff. This corporation has extensive foreign contacts and a well-developed network of partners, especially in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.[1]

Modern relations

The relations between Transnistria and Ukraine have changed on several times, depending on the foreign policy orientation of the government in Kyiv. In 2012, Marcin Kosienkowski defined Ukraine as Transnistria's "main window to the outside world" as a result of Transnistria being in conflict with its parent state Moldova.[2] Currently, about 29% of the Transnistrian population is ethnically Ukrainian.[3]

In June 1992, then Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk said that Ukraine would guarantee the independence of Transnistria in case of a Moldovan-Romanian union.[4] In secret, Ukrainian authorities negotiated with the government of Transnistria with the goal of Transnistria joining Ukraine.[5]

In 2001, representatives of the European Union asked the Ukrainian government to close the Transnistrian–Ukrainian border. The Ukrainian government under Leonid Kuchma ignored these requests.[6]

Between late 2004 and early 2005, the Orange Revolution changed the government in Ukraine, with Viktor Yushchenko becoming the new president. In 2006, Yushchenko's government began co-operating with the EU and the central government in Moldova in order to control the cross-border traffic from and to Transnistria.[7] Already in 2005, the European Union Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine had begun. In early 2006, the Ukrainian government allowed cross-border traffic that crossed the border without being inspected by the EUBAM mission.[8] In 2005, Petro Poroshenko was the Secretary of the Ukrainian National Security and Defense Council. Within the Orange government, he was accused of lobbying for Transnistria within the pro-Western Ukrainian camp.[9]

In the summer of 2006, Ukrainian foreign minister Borys Tarasyuk visited Transnistria, but did not meet with Transnistrian officials. He however visited the grave of Ivan Mazepa in Bender. His visit was disrupted by anti-NATO demonstrators.[10]

As of 2009, Ukrainian entrepreneurs held about one third of the Transnistrian economy. This included shares of Moldova Steel Works held by Hryhoriy Surkis, Ihor Kolomoyskyi, Alisher Usmanov, Vadym Novynskyi and Rinat Akhmetov.[11]

During the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine supported the Russian stance towards Transnistria.[12] In the course of the presidency, Ukraine supported a tactic of "small steps" in the 5+2 talks on the settlement of the Transnistria conflict.[13]

The 2014 Ukrainian Crisis had mostly economic repercussions on Transnistria.[14] In the aftermath of the 2014 Odesa clashes Ukrainian officials claimed that Russian nationals from Transnistria were involved in those clashes.[15]

In 2014, Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko has said that Transnistria is not a sovereign state, but rather, the name of a region along the Ukraine–Moldova border.[16]

In 2017, Transnistrian president Vadim Krasnoselsky said that Transnistria had "traditionally good relations with (Ukraine), we want to maintain them" and "we must build our relations with Ukraine – this is an objective necessity".[17]

After winning the 2019 Ukrainian presidential election, the new Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy held a press conference with then-Moldovan prime-minister (and now Moldovan president) Maia Sandu and assured his support of the territorial integrity of Moldova.[18]

Relations were strained during the

In March 2023, security services in Transnistria accused the Ukrainian government of attempting to assassinate top Transnistrian officials, including Vadim Krasnoselsky. The Ukrainian government rejected the allegations.[25]

See also

References

- ^ Kamil Całus: An aided economy. The characteristics of the Transnistrian economic model, osw.waw.pl/en/ 16 May 2013.

- ^ Marcin Kosienkowski: Continuity and Change in Transnistria's Foreign Policy After the 2011 Presidential Elections, Lublin: The Catholic University of Lublin Publishing House 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Vladimir Korobov/Georgiy Byanov: Ukraine: Inconsistent Policy toward Moldova, in: Marcin Kosienkowski/William Schreiber (eds.): Moldova: Arena of International Influences, Lanham (MD): Lexington Books 2012, pp. 219–235 (here: p. 219).

- ^ Moldawiens Präsident: Wir haben Krieg mit Rußland, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 23. June 1992.

- ^ Vladimir Korobov/Georgiy Byanov: Ukraine: Inconsistent Policy toward Moldova, in: Marcin Kosienkowski/William Schreiber (eds.): Moldova: Arena of International Influences, Lanham (MD): Lexington Books 2012, pp. 219–235 (here: p. 221).

- ^ Vladimir Socor: Poroshenko Drafts, Yushchenko Launches a Plan for Transnistria, jamestown.org 27 April 2005.

- ^ Vladimir Socor: Ukraine Steps in to Close Europe’s biggest Black Hole, jamestown.org 8 March 2006.

- ^ Vladimir Socor: Ukraine Breaking Ranks with Europe and Moldova on Transnistria, jamestown.org 23 March 2006.

- ^ Strategic and Security Studies Group (eds.): Transnistrian Problem: A View from Ukraine, Kyiv 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Vladimir Socor: Orange Two Government Can Meet the Transnistria Challenge, jamestown.org 29 June 2006.

- ^ Strategic and Security Studies Group (eds.): Transnistrian Problem: A View from Ukraine, Kyiv 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Ukraine supports the Russian position on Transnistria, osw.waw.pl/en/ 19 May 2010.

- ^ Hanna Shelest: Ukraine Pursues ‘Small-Steps’ Tactics in 5+2 Talks on Transnistrian Conflict Settlement, jamestown.org 6 November 2013.

- ^ David X. Noack: Tor geschlossen, jungewelt.de 15 July 2014 (in German).

- ^ "Наразі пожежа вже ліквідована, проте її причини досі невідомі". TSN.ua. 2 May 2014.

- UNIAN(in Russian). 23 October 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ Президент Приднестровья рассказал, почему не подпишет "Меморандум Козака-2", mk.ru 9 November 2017.

- ^ Ukraine to actively participate in negotiation process on Transnistria – Zelensky, ukrinform.net 12 July 2019.

- ^ Mădălin Necșuțu: Moldova Concerned About Possible Attack from Russian-Backed Region, balkaninsight.com 25 February 2022.

- ^ Keith Harrington: Moldova’s Rebel Region Stays Neutral in Russia’s War on Ukraine, balkaninsight.com 11 March 2022.

- ^ Iulian Ernst: Ukraine blows up bridge to Transnistria after Tiraspol reasserts its independence, intellinews.com 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Moldova's Rebel Region Stays Neutral in Russia's War on Ukraine". Balkan Insight. 2022-03-11. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "Ukrainian Presidential Office comments on events in Transnistrian region". report.az. Retrieved 2022-05-06.

- ^ "Löst der Krieg gegen die Ukraine den Transnistrien-Konflikt?". dw.com (in German). Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ "Transnistria: Ukraine denies attempt on Moldova separatist leader". dw.com. Retrieved 2023-06-30.