Transposable element

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a

Transposable elements make up a large fraction of the genome and are responsible for much of the

There are at least two classes of TEs: Class I TEs or

Discovery by Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock discovered the first TEs in maize (Zea mays) at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. McClintock was experimenting with maize plants that had broken chromosomes.[7]

In the winter of 1944–1945, McClintock planted corn kernels that were self-pollinated, meaning that the silk (

McClintock also showed that gene mutations could be reversed.[9] She presented her report on her findings in 1951, and published an article on her discoveries in Genetics in November 1953 entitled "Induction of Instability at Selected Loci in Maize".[10]

At the 1951 Cold Spring Harbor Symposium where she first publicized her findings, her talk was met with dead silence.[11] Her work was largely dismissed and ignored until the late 1960s–1970s when, after TEs were found in bacteria, it was rediscovered.[12] She was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983 for her discovery of TEs, more than thirty years after her initial research.[13]

Classification

Transposable elements represent one of several types of mobile genetic elements. TEs are assigned to one of two classes according to their mechanism of transposition, which can be described as either copy and paste (Class I TEs) or cut and paste (Class II TEs).[14]

Retrotransposon

Class I TEs are copied in two stages: first, they are

Retrotransposons are commonly grouped into three main orders:

- Retrotransposons, with long terminal repeats (LTRs), which encode reverse transcriptase, similar to retroviruses

- Retroposons, long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs, LINE-1s, or L1s), which encode reverse transcriptase but lack LTRs, and are transcribed by RNA polymerase II

- Short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) do not encode reverse transcriptase and are transcribed by RNA polymerase III

Retroviruses can also be considered TEs. For example, after the conversion of retroviral RNA into DNA inside a host cell, the newly produced retroviral DNA is integrated into the

DNA transposons

B. Mechanism of transposition: Two transposases recognize and bind to TIR sequences, join and promote DNA double-strand cleavage. The DNA-transposase complex then inserts its DNA cargo at specific DNA motifs elsewhere in the genome, creating short TSDs upon integration.[15]

The cut-and-paste transposition mechanism of class II TEs does not involve an RNA intermediate. The transpositions are catalyzed by several

Cut-and-paste TEs may be duplicated if their transposition takes place during S phase of the cell cycle, when a donor site has already been replicated but a target site has not yet been replicated.[citation needed] Such duplications at the target site can result in gene duplication, which plays an important role in genomic evolution.[16]: 284

Not all DNA transposons transpose through the cut-and-paste mechanism. In some cases, a replicative transposition is observed in which a transposon replicates itself to a new target site (e.g. helitron).

Class II TEs comprise less than 2% of the human genome, making the rest Class I.[17]

Autonomous and non-autonomous

Transposition can be classified as either "autonomous" or "non-autonomous" in both Class I and Class II TEs. Autonomous TEs can move by themselves, whereas non-autonomous TEs require the presence of another TE to move. This is often because dependent TEs lack transposase (for Class II) or reverse transcriptase (for Class I).

Activator element (Ac) is an example of an autonomous TE, and dissociation elements (Ds) is an example of a non-autonomous TE. Without Ac, Ds is not able to transpose.

Class III

Some researchers also identify a third class of transposable elements,[18] which has been described as "a grab-bag consisting of transposons that don't clearly fit into the other two categories".[19] Examples of such TEs are the Foldback (FB) elements of Drosophila melanogaster, the TU elements of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, and Miniature Inverted-repeat Transposable Elements.[20][21]

Distribution

Approximately 64% of the maize genome is made up of TEs,[22][23] as is 44% of the human genome,[24] and almost half of murine genomes.[25]

This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (August 2021) |

New discoveries of transposable elements have shown the exact distribution of TEs with respect to their transcription start sites (TSSs) and enhancers. A recent study found that a promoter contains 25% of regions that harbor TEs. It is known that older TEs are not found in TSS locations because TEs frequency starts as a function once there is a distance from the TSS. A possible theory for this is that TEs might interfere with the transcription pausing or the first-intro splicing.[26] Also as mentioned before, the presence of TEs closed by the TSS locations is correlated to their evolutionary age (number of different mutations that TEs can develop during the time).

Examples

- The first TEs were discovered in Ac/Ds system described by McClintock are Class II TEs. Transposition of Ac in tobacco has been demonstrated by B. Baker.[27]

- In the pond microorganism, Oxytricha, TEs play such a critical role that when removed, the organism fails to develop.[28]

- One family of TEs in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster are called P elements. They seem to have first appeared in the species only in the middle of the twentieth century; within the last 50 years, they spread through every population of the species. Gerald M. Rubin and Allan C. Spradling pioneered technology to use artificial P elements to insert genes into Drosophila by injecting the embryo.[29][30][31]

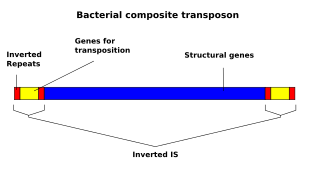

- In multi-antibiotic resistant bacterial strains can be generated in this way). Bacterial transposons of this type belong to the Tn family. When the transposable elements lack additional genes, they are known as insertion sequences.

- In Alu sequence. It is approximately 300 bases long and can be found between 300,000 and one million times in the human genome. Alu alone is estimated to make up 15–17% of the human genome.[17]

- animals were found in Trichomonas vaginalis.[36]

- Mu phage transposition is the best-known example of replicative transposition.

- In Yeast genomes (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) there are five distinct retrotransposon families: Ty1, Ty2, Ty3, Ty4 and Ty5.[37]

- A helitron is a TE found in eukaryotes that is thought to replicate by a rolling-circle mechanism.

- In human embryos, two types of transposons combined to form noncoding RNA that catalyzes the development of stem cells. During the early stages of a fetus's growth, the embryo's inner cell mass expands as these stem cells enumerate. The increase of this type of cells is crucial, since stem cells later change form and give rise to all the cells in the body.

- In peppered moths, a transposon in a gene called cortex caused the moths' wings to turn completely black. This change in coloration helped moths to blend in with ash and soot-covered areas during the Industrial Revolution.[38]

- Aedes aegypti carries a large and diverse number of TEs. This analysis by Matthews et al. 2018 also suggests this is common to all mosquitoes.[39]

Negative effects

Transposons have coexisted with eukaryotes for thousands of years and through their coexistence have become integrated in many organisms' genomes. Colloquially known as 'jumping genes', transposons can move within and between genomes allowing for this integration.

While there are many positive effects of transposons in their host eukaryotic genomes,[further explanation needed] there are some instances of mutagenic effects that TEs have on genomes leading to disease and malignant genetic alterations.[40]

Mechanisms of mutagenesis

TEs are mutagens and due to the contribution to the formation of new cis-regulatory DNA elements that are connected to many transcription factors that are found in living cells; TEs can undergo many evolutionary mutations and alterations. These are often the causes of genetic disease, and gives the potential lethal effects of ectopic expression.[26]

TEs can damage the genome of their host cell in different ways:[40]

- A transposon or a retrotransposon that inserts itself into a functional gene can disable that gene.

- After a DNA transposon leaves a gene, the resulting gap may not be repaired correctly.

- Multiple copies of the same sequence, such as Alu sequences, can hinder precise chromosomal pairing during mitosis and meiosis, resulting in unequal crossovers, one of the main reasons for chromosome duplication.

TEs use a number of different mechanisms to cause genetic instability and disease in their host genomes.

- Expression of disease-causing, damaging proteins that inhibit normal cellular function.

- Many TEs contain phenotypes.[41]

- Many TEs contain

Diseases

Diseases often caused by TEs include

- HemophiliaA and B

- Severe combined immunodeficiency

- Insertion of L1 into the APC gene causes colon cancer, confirming that TEs play an important role in disease development.[43]

- Porphyria

- Insertion of Alu element into the PBGD gene leads to interference with the coding region and leads to acute intermittent porphyria[44] (AIP).

- Predisposition to cancer

- LINE1(L1) TE's and other retrotransposons have been linked to cancer because they cause genomic instability.[42]

- Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[45][46]

- Caused by SVA transposable element insertion in the fukutin (FKTN) gene which renders the gene inactive.[42]

- Alzheimer's Disease and other Tauopathies

- Transposable element dysregulation can cause neuronal death, leading to neurodegenerative disorders[47]

Rate of transposition, induction and defense

One study estimated the rate of transposition of a particular retrotransposon, the Ty1 element in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Using several assumptions, the rate of successful transposition event per single Ty1 element came out to be about once every few months to once every few years.[48] Some TEs contain heat-shock like promoters and their rate of transposition increases if the cell is subjected to stress,[49] thus increasing the mutation rate under these conditions, which might be beneficial to the cell.

Cells defend against the proliferation of TEs in a number of ways. These include

TEs after they have been transcribed.If organisms are mostly composed of TEs, one might assume that disease caused by misplaced TEs is very common, but in most cases TEs are silenced through epigenetic mechanisms like DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling and piRNA, such that little to no phenotypic effects nor movements of TEs occur as in some wild-type plant TEs. Certain mutated plants have been found to have defects in methylation-related enzymes (methyl transferase) which cause the transcription of TEs, thus affecting the phenotype.[6][51]

One hypothesis suggests that only approximately 100 LINE1 related sequences are active, despite their sequences making up 17% of the human genome. In human cells, silencing of LINE1 sequences is triggered by an

Evolution

TEs are found in almost all life forms, and the scientific community is still exploring their evolution and their effect on genome evolution. It is unclear whether TEs originated in the

Because excessive TE activity can damage

The frequency and location of TE integrations influence genomic structure and evolution and affect gene and protein regulatory networks during development and in differentiated cell types.

TEs can contain many types of genes, including those conferring antibiotic resistance and the ability to transpose to conjugative plasmids. Some TEs also contain integrons, genetic elements that can capture and express genes from other sources. These contain integrase, which can integrate gene cassettes. There are over 40 antibiotic resistance genes identified on cassettes, as well as virulence genes.

Transposons do not always excise their elements precisely, sometimes removing the adjacent base pairs; this phenomenon is called exon shuffling. Shuffling two unrelated exons can create a novel gene product or, more likely, an intron.[63]

Some non-autonomous DNA TEs found in plants can capture coding DNA from genes and shuffle them across the genome.[64] This process can duplicate genes in the genome (a phenomenon called transduplication), and can contribute to generate novel genes by exon shuffling.[65]

Evolutionary drive for TEs on the genomic context

There is a hypothesis that states that TEs might provide a ready source of DNA that could be co-opted by the cell to help regulate gene expression. Research showed that many diverse modes of TEs co-evolution along with some transcription factors targeting TE-associated genomic elements and chromatin are evolving from TE sequences. Most of the time, these particular modes do not follow the simple model of TEs and regulating host gene expression.[26]

Applications

Transposable elements can be harnessed in laboratory and research settings to study genomes of organisms and even engineer genetic sequences. The use of transposable elements can be split into two categories: for genetic engineering and as a genetic tool.

Genetic engineering

- Insertional mutagenesis uses the features of a TE to insert a sequence. In most cases, this is used to remove a DNA sequence or cause a frameshift mutation.

- In some cases the insertion of a TE into a gene can disrupt that gene's function in a reversible manner where transposase-mediated excision of the DNA transposon restores gene function.

- This produces plants in which neighboring cells have different genotypes.

- This feature allows researchers to distinguish between genes that must be present inside of a cell in order to function (cell-autonomous) and genes that produce observable effects in cells other than those where the gene is expressed.

Genetic tool

In addition to the qualities mentioned for Genetic engineering, a Genetic tool also:-

- Used for analysis of gene expression and protein functioning in signature-tagging mutagenesis.

- This analytical tool allows researchers the ability to determine phenotypic expression of gene sequences. Also, this analytic technique mutates the desired locus of interest so that the phenotypes of the original and the mutated gene can be compared.

Specific applications

- TEs are also a widely used tool for mutagenesis of most experimentally tractable organisms. The Sleeping Beauty transposon system has been used extensively as an insertional tag for identifying cancer genes.[66]

- The Tc1/mariner-class of TEs Sleeping Beauty transposon system, awarded Molecule of the Year in 2009,[67] is active in mammalian cells and is being investigated for use in human gene therapy.[68][69][70]

- TEs are used for the reconstruction of phylogenies by the means of presence/absence analyses.[71] Transposons can act as biological mutagen in bacteria.

- Common organisms which the use of Transposons has been well developed are:

De novo repeat identification

De novo repeat identification is an initial scan of sequence data that seeks to find the repetitive regions of the genome, and to classify these repeats. Many computer programs exist to perform de novo repeat identification, all operating under the same general principles.[67] As short tandem repeats are generally 1–6 base pairs in length and are often consecutive, their identification is relatively simple.[66] Dispersed repetitive elements, on the other hand, are more challenging to identify, due to the fact that they are longer and have often acquired mutations. However, it is important to identify these repeats as they are often found to be transposable elements (TEs).[67]

De novo identification of transposons involves three steps: 1) find all repeats within the genome, 2) build a

The second step of de novo repeat identification involves building a consensus of each family of sequences. A consensus sequence is a sequence that is created based on the repeats that comprise a TE family. A base pair in a consensus is the one that occurred most often in the sequences being compared to make the consensus. For example, in a family of 50 repeats where 42 have a T base pair in the same position, the consensus sequence would have a T at this position as well, as the base pair is representative of the family as a whole at that particular position, and is most likely the base pair found in the family's ancestor at that position.[67] Once a consensus sequence has been made for each family, it is then possible to move on to further analysis, such as TE classification and genome masking in order to quantify the overall TE content of the genome.

Adaptive TEs

Transposable elements have been recognized as good candidates for stimulating gene adaptation, through their ability to regulate the expression levels of nearby genes.[69] Combined with their "mobility", transposable elements can be relocated adjacent to their targeted genes, and control the expression levels of the gene, dependent upon the circumstances.

The study conducted in 2008, "High Rate of Recent Transposable Element–Induced Adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster", used D. melanogaster that had recently migrated from Africa to other parts of the world, as a basis for studying adaptations caused by transposable elements. Although most of the TEs were located on introns, the experiment showed a significant difference in gene expressions between the population in Africa and other parts of the world. The four TEs that caused the selective sweep were more prevalent in D. melanogaster from temperate climates, leading the researchers to conclude that the selective pressures of the climate prompted genetic adaptation.[70] From this experiment, it has been confirmed that adaptive TEs are prevalent in nature, by enabling organisms to adapt gene expression as a result of new selective pressures.

However, not all effects of adaptive TEs are beneficial to the population. In the research conducted in 2009, "A Recent Adaptive Transposable Element Insertion Near Highly Conserved Developmental Loci in Drosophila melanogaster", a TE, inserted between Jheh 2 and Jheh 3, revealed a downgrade in the expression level of both of the genes. Downregulation of such genes has caused Drosophila to exhibit extended developmental time and reduced egg to adult viability. Although this adaptation was observed in high frequency in all non-African populations, it was not fixed in any of them.[71] This is not hard to believe, since it is logical for a population to favor higher egg to adult viability, therefore trying to purge the trait caused by this specific TE adaptation.

At the same time, there have been several reports showing the advantageous adaptation caused by TEs. In the research done with silkworms, "An Adaptive Transposable Element insertion in the Regulatory Region of the EO Gene in the Domesticated Silkworm", a TE insertion was observed in the cis-regulatory region of the EO gene, which regulates molting hormone 20E, and enhanced expression was recorded. While populations without the TE insert are often unable to effectively regulate hormone 20E under starvation conditions, those with the insert had a more stable development, which resulted in higher developmental uniformity.[73]

These three experiments all demonstrated different ways in which TE insertions can be advantageous or disadvantageous, through means of regulating the expression level of adjacent genes. The field of adaptive TE research is still under development and more findings can be expected in the future.

TEs participates in gene control networks

Recent studies have confirmed that TEs can contribute to the generation of transcription factors. However, how this process of contribution can have an impact on the participation of genome control networks. TEs are more common in many regions of the DNA and it makes up 45% of total human DNA. Also, TEs contributed to 16% of transcription factor binding sites. A larger number of motifs are also found in non-TE-derived DNA, and the number is larger than TE-derived DNA. All these factors correlate to the direct participation of TEs in many ways of gene control networks.[26]

See also

- Decrease in DNA Methylation I (DDM1)

- Evolution of sexual reproduction

- Insertion sequence

- Intragenomic conflict

- P element

- Polinton

- Signature tagged mutagenesis

- Tn3 transposon

- Tn10

- Transpogene

- Transposon tagging

Notes

- Kidwell MG (2005). "Transposable elements". In T.R. Gregory (ed.). ISBN 978-0-123-01463-4.

- Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, and Lambowitz AM, eds. (2002). Mobile DNA II. Washington, DC: ASM Press. ISBN 978-1-555-81209-6.

- Lewin B (2000). Genes VII. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-79276-5.

References

- PMID 30454069.

- PMID 35357911.

- PMID 15430309.

- PMID 35337342.

- PMID 22940592.

- ^ a b c Pray LA (2008). "Transposons: The jumping genes". Nature Education. 1 (1): 204.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9702256-0-3.

- ^ a b c McGrayne 1998, p. 166

- ^ McGrayne 1998, p. 167

- PMID 17247459.

- PMID 23236127.

- ISBN 978-1-55861-655-4.

- ISBN 978-0-87969-422-7.

- S2CID 1275744.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-13-144329-7.

- ^ S2CID 33460203.

- ISBN 978-3-540-61190-5.

- ^ Baez J (2005). "Subcellular Life Forms" (PDF).

- PMID 29941591.

- PMID 12537573.

- S2CID 33433647.

- ^ PMID 28605751.

- PMID 17331616.

- S2CID 202572327.

- ^ PMID 32719115.

- ^ Plant Transposable Elements, ed. Nelson (Plenum Publishing, 1988), pp. 161–174.

- PMID 19372392.

- "'Junk' DNA Has Important Role, Researchers Find". ScienceDaily (Press release). 21 May 2009.

- PMID 6289435.

- PMID 6289436.

- doi:10.1038/nrg2254.

- PMID 3022302.

- PMID 7877497.

- PMID 12654937.

- S2CID 82147.

- PMID 17218520.

- PMID 9582191.

- S2CID 3989607.

- PMID 31481535.

- ^ PMID18256243.

- PMID 32561758.

- ^ PMID2831458.

- PMID1310068.

- S2CID 6218429.

- PMID12176313.

- ISBN 978-3527600908.

- PMID30038280.

- S2CID 39145808.

- PMID 2409535.

- PMID 18501606.

- ^ S2CID 4429219.

- S2CID 32601334.

- S2CID 33227644.

- ^ Villarreal L (2005). Viruses and the Evolution of Life. Washington: ASM Press.

- PMID 29855654.

- PMID 10431195.

- S2CID 17908472.

- PMID 17403897.

- ^ "Gene group: Transposable element derived genes". HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- PMID 24039890.

- PMID 33043724.

- PMID 19472181.

- PMID 10066175.

- S2CID 4363679.

- PMID 30476196.

- ^ S2CID 26272439.

- ^ PMID 22407715.

- ^ PMID 18287116.

- ^ PMID 16093685.

- ^ PMID 18942889.

- ^ PMID 19458110.

- PMID 20860790.

- PMID 25213334.

External links

- "An immune system so versatile it might kill you". New Scientist (2556). 21 June 2006. – A possible connection between aberrant reinsertions and lymphoma.

- Repbase – a database of transposable element sequences

- Dfam - a database of transposable element families, multiple sequence alignments, and sequence models

- RepeatMasker – a computer program used by computational biologists to annotate transposons in DNA sequences

- Use of the Sleeping Beauty Transposon System for Stable Gene Expression in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Introduction to Transposons, 2018 YouTube video