Transthyretin

| TTR | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Gene ontology | |||

| Molecular function | |||

| Cellular component | |||

| Biological process | |||

| Sources:Amigo / QuickGO | |||

Ensembl | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | |||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 18: 31.56 – 31.6 Mb | Chr 18: 20.8 – 20.81 Mb | |||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Transthyretin (TTR or TBPA) is a

TTR was originally called prealbumin[5] (or thyroxine-binding prealbumin) because it migrated faster than albumin on electrophoresis gels. Prealbumin was felt to be a misleading name, it is not a synthetic precursor of albumin. The alternative name TTR was proposed by DeWitt Goodman in 1981.

Transthyretin protein is encoded by the TTR gene located on the 18th chromosome.

Binding affinities

It functions in concert with two other thyroid hormone-binding proteins in the serum:

| Protein | Binding strength | Plasma concentration |

|---|---|---|

| thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) | highest | lowest |

| transthyretin (TTR or TBPA) | lower | higher |

| albumin | poorest | much higher |

In cerebrospinal fluid TTR is the primary carrier of T4. TTR also acts as a carrier of retinol (vitamin A) through its association with retinol-binding protein (RBP) in the blood and the CSF. Less than 1% of TTR's T4 binding sites are occupied in blood, which is taken advantage of below to prevent TTRs dissociation, misfolding and aggregation which leads to the degeneration of post-mitotic tissue.

Numerous other small molecules are known to bind in the thyroxine binding sites, including many natural products (such as resveratrol), drugs (tafamidis,[6] diflunisal,[7][8][9] and flufenamic acid),[10] and toxicants (PCB[11]).

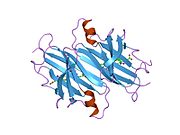

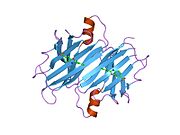

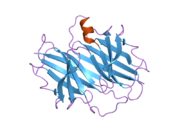

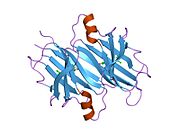

Structure

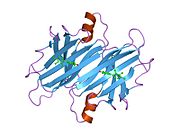

TTR is a 55kDa homotetramer with a dimer of dimers quaternary structure that is synthesized in the

Role in disease

TTR misfolding and aggregation is known to be associated with amyloid diseases[13] including wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis,[14] hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis,[15] familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP),[16][17] and familial amyloid cardiomyopathy (FAC).[18]

TTR tetramer dissociation is known to be rate-limiting for amyloid fibril formation.[19][20][21] However, the monomer also must partially denature in order for TTR to be mis-assembly competent, leading to a variety of aggregate structures, including amyloid fibrils.[22]

At least 114 disease-causing mutations in this gene have been discovered.[23] While wild type TTR can dissociate, misfold, and aggregate, leading to SSA (senile systemic amyloidosis), point mutations within TTR are known to destabilize the tetramer composed of mutant and wild-type TTR subunits, facilitating more facile dissociation and/or misfolding and amyloidogenesis.[24] A replacement of valine by methionine at position 30 (TTR V30M) is the mutation most commonly associated with FAP.[25] A position 122 replacement of valine by isoleucine (TTR V122I) is carried by 3.9% of the African-American population, and is the most common cause of FAC.[18] SSA is estimated to affect over 25% of the population over age 80.[14] Severity of disease varies greatly by mutation, with some mutations causing disease in the first or second decade of life, and others being more benign. Deposition of TTR amyloid is generally observed extracellularly, although TTR deposits are also clearly observed within the cardiomyocytes of the heart.

Treatment of familial (hereditary) TTR amyloid disease has historically relied on liver transplantation as a crude form of gene therapy.[26] Because TTR is primarily produced in the liver, replacement of a liver containing a mutant TTR gene with a normal gene is able to reduce the mutant TTR levels in the body to < 5% of pretransplant levels. Certain mutations, however, cause CNS amyloidosis, and due to their production by the choroid plexus, the CNS TTR amyloid diseases do not respond to gene therapy mediated by liver transplantation.

In 2011, the European Medicines Agency approved tafamidis (Vyndaqel) for the amelioration of FAP.[6] Tafamidis kinetically stabilizes the TTR tetramer, preventing tetramer dissociation required for TTR amyloidogenesis and degradation of the autonomic nervous system[27] and/or the peripheral nervous system and/or the heart.[21]

TTR is also thought to have beneficial side effects, by binding to the infamous

There is now strong genetic

Transthyretin level in cerebrospinal fluid has also been found to be lower in patients with some

Transthyretin is known to contain a Gla domain, and thus be dependent for production on post-translational modification requiring vitamin K, but the potential link between vitamin k status and thyroid function has not been explored.

Because transthyretin is made in part by the choroid plexus, it can be used as an immunohistochemical marker for choroid plexus papillomas as well as carcinomas.[citation needed]

As of March 2015, there are two ongoing clinical trials undergoing recruitment in the United States and worldwide to evaluate potential treatments for TTR amyloidosis.[34][needs update]

Interactions

Transthyretin has been shown to

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000118271 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000061808 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Prealbumin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ PMID 12820260.

- S2CID 32736564.

- PMID 14711308.

- ISBN 978-1-4200-4281-8.

- PMID 10465408.

- PMID 15610856.

- PMID 16300401.

- ISBN 978-0-471-79928-3.

- ^ PMID 2320592.

- ^ "Familial amyloid polyneuropathy", Wikipedia, 2021-11-02, retrieved 2021-12-05

- PMID 12978172.

- S2CID 43007619.

- ^ PMID 9017939.

- PMID 1390650.

- PMID 8639594.

- ^ S2CID 30829998.

- PMID 11560492.

- PMID 31819097.

- S2CID 12503292.

- S2CID 10124222.

- S2CID 26093858.

- PMID 10036588.

- PMID 22112803.

- ^ Coelho, T., Carvalho, M., Saraiva, M.J., Alves, I., Almeida, M.R., and Costa, P.P. (1993). A strikingly benign evolution of FAP in an individual found to be a compound heterozygote for two TTR mutations: TTR MET 30 and TTR MET 119. J Rheumatol 20, 179.

- S2CID 39689656.

- PMID 11733349.

- PMID 14981241.

- PMID 17090210.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT01960348 for "APOLLO: The Study of an Investigational Drug, Patisiran (ALN-TTR02), for the Treatment of Transthyretin (TTR)-Mediated Amyloidosis" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- PMID 9307034.

Further reading

- Sakaki Y, Yoshioka K, Tanahashi H, Furuya H, Sasaki H (1989). "Human transthyretin (prealbumin) gene and molecular genetics of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy". Mol. Biol. Med. 6 (2): 161–8. PMID 2693890.

- Saraiva MJ (1995). "Transthyretin mutations in health and disease". Hum. Mutat. 5 (3): 191–6. S2CID 10124222.

- Ingenbleek Y, Young V (1994). "Transthyretin (prealbumin) in health and disease: nutritional implications". Annu. Rev. Nutr. 14: 495–533. PMID 7946531.

- Hesse A, Altland K, Linke RP, Almeida MR, Saraiva MJ, Steinmetz A, Maisch B (1993). "Cardiac amyloidosis: a review and report of a new transthyretin (prealbumin) variant". Br Heart J. 70 (2): 111–5. PMID 8038017.

- Blanco-Jerez CR, Jiménez-Escrig A, Gobernado JM, Lopez-Calvo S, de Blas G, Redondo C, García Villanueva M, Orensanz L (1998). "Transthyretin Tyr77 familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a clinicopathological study of a large kindred". Muscle Nerve. 21 (11): 1478–85. S2CID 19532662.