Treaty of Georgievsk

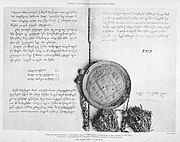

A photograph of the Georgian version of the Treaty of Georgievsk with Heraclius II's signature and seal, c. 1913 | |

| Signed | July 24, 1783 |

|---|---|

| Location | Georgiyevsk, Russian Empire |

| Sealed | 1784 |

| Effective | 1784 |

| Signatories | |

| Full text | |

The Treaty of Georgievsk (

Terms

Under articles I, II, IV, VI and VII of the treaty's terms, Russia's empress became the official and sole suzerain of Kartli-Kakheti's rulers, guaranteeing the Georgians’ internal sovereignty and territorial integrity, and promising to "regard their enemies as Her enemies" [3] Each of the Georgian kingdom's

Given Georgia's history of invasions from the south, an alliance with Russia may have been seen as the only way to discourage or resist

Other treaty provisions included mutual guarantees of an open border between the two realms for travelers, emigrants and merchants (articles 10, 11), while Russia undertook "to leave the power for internal administration, law and order, and the collection of taxes [under the] complete will and use of His Serene Highness the Tsar, forbidding [Her Majesty’s] Military and Civil Authorities to intervene in any [domestic laws or commands]".

(article VI).

The treaty was negotiated on behalf of Russia by

]Aftermath

The results of the Treaty of Georgievsk proved disappointing for the Georgians.

On January 14, 1798, King Erekle II was succeeded on the throne by his eldest son, George XII (1746–1800) who, on February 22, 1799, recognized his own eldest son,

Paul tentatively accepted this offer, but before negotiations could be finalized changed his mind and issued a decree on December 18, 1800

The Russians then ended the

Paul's annexation of east Georgia and exile of the Bagratids remain controversial: Soviet historians would later maintain that the treaty was an act of "brotherhood of the Russian and Georgian peoples" that justified annexation to protect Georgia both from its historical foreign persecutors and its "decadent" native dynasty. Nonetheless, no bilateral amendment had been ratified altering article VI sections 2 and 3 of the 1784 treaty, which obligated the Russian emperor "to preserve His Serene Highness Tsar Irakli Teimurazovich and the Heirs and descendants to his House, uninterrupted on the Throne of the Kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti...forbidding [Her Majesty’s] Military and Civil Authorities to intervene in any [domestic laws or commands]."[3]

Legacy

Ironically, that clause of the treaty would also be recalled during obscure late 20th century debates about restoration of the Russian monarchy.

Critics deny that Princess Leonida could be reckoned of royal rank by Romanov standards (the title of

While these facts are admitted, it is counter-argued that the demotion of the Bagratids, including the Mukhrani branch, violated the Treaty of Georgievsk and therefore failed to legally deprive any

The language of article VI guaranteed the Georgian throne not only to King Erekle II and his direct issue, but also embraced "the Heirs and descendants to his House".[3][10] On the other hand, article IX offered to extend no more than "the same privileges and advantages granted to the Russian nobility" to Georgia's princes and nobles.[3] Yet first on the list of families submitted to Russia to enjoy noble (not royal) status was that of the Mukhranbatoni. That list included twenty-one other princely families and a larger number of untitled nobles, most of whom were enrolled in Russia's nobility during the 19th century. The claims made on Maria's behalf have long embittered Romanov descendants who belong to the Romanov Family Association. Many of them descend matrilineally from noble Russian princesses, some of whose families were also of "dynastic" origin, but cannot claim that a Treaty of Georgievsk has "preserved" their "dynasticity".[citation needed]

In 1983, the

References

- ^ "Art".

- ^ a b c d Anchabadze, George, Ph.D. History of Georgia. Georgia in the Beginning of Feudal Decomposition. (XVIII cen.). Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Treaty of Georgievsk, 1783. PSRZ, vol. 22 (1830), pp. 1013–1017. Translated from the Russian by Russell E. Martin, Ph.D., Westminster College.

- ^ Perry 2006, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1991, pp. 328–330.

- ISBN 0-85011-029-7

- ^ Tsagareli, A (1902). Charters and other historical documents of the XVIII century regarding Georgia. pp. 287–288.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica, "Treaty of Georgievsk", 2008, retrieved 2008-6-16

- ^ Mikaberidze 2015, pp. 348–349.

- ^ ISBN 91-630-5964-9.

- ^ Cyril Toumanoff, "The Fifteenth-Century Bagratides and the Institution of Collegial Sovereignty in Georgia". Traditio. Volume VII, Fordham University Press, New York 1949–1951, pp. 169–221

- ^ Frederiks, Baron V., Letter to Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, 1911-06-04, State Archives of the Russian Federation, Series 604, Inventory 1, File 2143, pages 58–59, retrieved 2008-11-04

- ^ (in Russian) Алексеева, Людмила (1983), Грузинское национальное движение. In: История Инакомыслия в СССР. Accessed on April 3, 2007.

Sources

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1991). "Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521200950.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Perry, John R. (2006). Karim Khan Zand. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1851684359.

- (in English) Anchabadze, Dr. George. History of Georgia

- Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh. 1980 "Burke’s Royal Families of the World: Volume II Africa & the Middle East", ISBN 0-85011-029-7

Further reading

- David Marshall Lang: The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy: 1658–1832. Columbia University Press, New York 1957.

- Nikolas K. Gvosdev, Imperial policies and perspectives towards Georgia: 1760–1819. Macmillan [u.a.], Basingstoke [u.a.] 2000, ISBN 0-312-22990-9.

- "Traité conclu en 1783 entre Cathérine II. impératrice de Russie et Iracly II. roi de Géorgie". Recueil des lois russes; vol. XXI, No. 15835, Avec une préface de M. Paul Moriaud, Professeur de da Faculté de Droit de l’université de Genève, et commentaires de A. Okouméli, Genève 1909.

- Zurab Avalov, Prisoedinenie Gruzii k Rossii. Montvid, S.-Peterburg 1906.

External links

- Treaty of Georgievsk (Translated from the Russian by Russell E. Martin, Westminster College)

- The Portfolio; A Collection of State Papers, and other Document and Correspondence, Historical, Diplomatic, and Commercial, Vol. V, pp. 206–209. London: 1837