Treaty of the Pyrenees

| Signed | 7 November 1659 |

|---|---|

| Location | Pheasant Island |

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories |

|

| Parties | |

The Treaty of the Pyrenees

Negotiations were conducted and the treaty was signed on

Background

France entered the Thirty Years' War after the

An Anglo-French alliance was victorious at the Battle of the Dunes on 14 June 1658, but the following year the war ground to a halt when the French campaign to take Milan was defeated. Peace was settled by means of the Treaty of the Pyrenees in November 1659.

Content

France gained

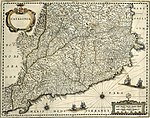

Spain was forced to recognize and confirm all of the French gains at the Peace of Westphalia.[4] In exchange for the Spanish territorial losses, the French king pledged to quit his support for Portugal and renounced his claim to the county of Barcelona, which the French crown had claimed ever since the Catalan Revolt (also known as Reapers' War).[4] The Portuguese revolt in 1640, led by the Duke of Braganza, was supported monetarily by Cardinal Richelieu of France. After the Catalan Revolt, France had controlled the Principality of Catalonia from January 1641, when a combined Catalan and French force defeated the Spanish army at Battle of Montjuïc, until it was defeated by a Spanish army at Barcelona in 1652.[6] Though the Spanish army reconquered most of Catalonia, the French retained Catalan territory north of the Pyrenees.

The treaty also arranged for a marriage between

In addition, the English received Dunkirk,[4] although they elected to sell it to France in 1662.

Consequences

The Treaty of the Pyrenees was the last major diplomatic achievement by Cardinal Mazarin. Combined with the

All in all, by 1660, when the

French annexations

In the context of the territorial changes involved in the Treaty, France gained some territory, on both its northern and southern borders.

- In the north, France gained Artois and smaller areas along its north-east border with the Holy Roman Empire.

- In the south:

- On the east: the northern part of the Principality of Catalonia, including Roussillon, Conflent, Vallespir, Capcir, and French Cerdagne, was transferred to France, i.e. what later came to be known as "Northern Catalonia".

- On the west: the parties agreed to put together a field group to compromise a borderline on disputed lands along the Basque Pyrenees, involving Sareta—Valcarlos.

See also

| History of Catalonia | |

|---|---|

| |

| 27 BC – 476 AD |