Trichomonas vaginalis

| Trichomonas vaginalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Trichomonas vaginalis observed by scanning electron microscopy showing the axostyle (ax), the anterior flagella (af) and the undulating membrane (rf).[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Metamonada |

| Order: | Trichomonadida |

| Family: | Trichomonadidae |

| Genus: | Trichomonas |

| Species: | T. vaginalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Trichomonas vaginalis (Donné 1836)

| |

Trichomonas vaginalis is an

Clinical

History

Mechanism of infection

Trichomonas vaginalis, a parasitic protozoan, is the etiologic agent of trichomoniasis, and is a sexually transmitted infection.[3][8] More than 160 million people worldwide are annually infected by this protozoan.[3]

Symptoms

Trichomoniasis, a sexually transmitted infection of the urogenital tract, is a common cause of vaginitis in women, while men with this infection can display symptoms of urethritis as well as symptoms of prostate infection.[9] 'Frothy', greenish vaginal discharge with a 'musty' malodorous smell is characteristic.[10]

Signs

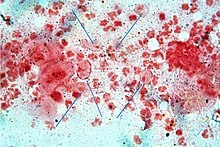

Only 2% of women with the infection will have a "strawberry" cervix (colpitis macularis, an erythematous cervix with pinpoint areas of exudation) or vagina on examination.[11][12][13] This is due to capillary hemorrhage.[14]

Complications

Some of the complications of T. vaginalis in women include:

Trichomonas vaginalis infection in males has been found to cause asymptomatic urethritis and prostatitis.[17] It has been proposed that it may increase the risk of prostate cancer; however, evidence is insufficient to support this association as of 2014.[17]

Diagnosis

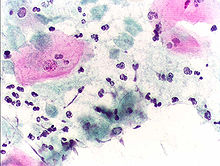

Classically, with a

Treatment

Infection is treated and cured with metronidazole[23] or tinidazole. The CDC recommends a one time dose of 2 grams of either metronidazole or tinidazole as the first-line treatment; the alternative treatment recommended is 500 milligrams of metronidazole, twice daily, for seven days if there is failure of the single-dose regimen.[24] Medication should be prescribed to any sexual partner(s) as well because they may be asymptomatic carriers.[10][25]

Morphology

Unlike other parasitic protozoa (

While T. vaginalis does not have a cyst form, organisms can survive for up to 24 hours in urine, semen, or even water samples. A nonmotile, round, pseudocystic form with internalized flagella has been observed under unfavorable conditions.[12] This form is generally regarded as a degenerate stage as opposed to a resistant form,[12] although viability of pseudocystic cells has been occasionally reported.[27] The ability to revert to trophozoite form, to reproduce and sustain infection has been described,[28] along with a microscopic cell staining technique to visually discern this elusive form.[29]

Protein function

T. vaginalis lacks

Virulence factors

One of the hallmark features of T. vaginalis is the adherence factors that allow

Genome sequencing and statistics

The T. vaginalis genome is approximately 160

In late 2007 TrichDB.org was launched as a free, public genomic data repository and retrieval service devoted to genome-scale trichomonad data. The site currently contains all of the T. vaginalis sequence project data, several EST libraries, and tools for data mining and display. TrichDB is part of the NIH/NIAID-funded EupathDB functional genomics database project.[36]

Genetic diversity

Recent studies into the genetic diversity of T. vaginalis has shown that there are two distinct lineages of the parasite found worldwide; both lineages are represented evenly in field isolates. The two lineages differ in whether or not T. vaginalis virus (TVV) infection is present. TVV infection in T. vaginalis is clinically relevant in that, when present, TVV has an effect on parasite resistance to metronidazole, a first line drug treatment for human trichomoniasis.[37]

Increased susceptibility to HIV

The damage caused by T. vaginalis to the vaginal epithelium increases a woman's susceptibility to an HIV infection. In addition to inflammation, the parasite also causes lysis of epithelial cells and RBCs in the area leading to more inflammation and disruption of the protective barrier usually provided by the epithelium. Having T. vaginalis also may increase the chances of the infected woman transmitting HIV to her sexual partner(s).[38][39]

Evolution

The biology of T. vaginalis has implications for understanding the origin of sexual reproduction in eukaryotes. T. vaginalis is not known to undergo

See also

- List of parasites (human)

References

- PMID 28953994.

- PMID 14749674.

- ^ PMID 21440359.

- PMID 10458631.

- ^ W Evan Secor. "Trichomonas Vaginalis". MedScape.

- ^ Donné, A. (19 September 1836). "Animalcules observés dans les matières purulentes et le produit des sécrétions des organes génitaux de l'homme et de la femme". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 3: 385–386.

- S2CID 9287263.

- S2CID 39490032.

- ^ ISBN 9780891891673.

- ^ S2CID 43515177.

- PMID 15054166.

- ^ PMID 9564565.

- PMID 18159526.

- PMID 23508486.

- PMID 15489349.

- ^ "Trichomoniasis". CDC Fact Sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007-12-17. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ PMID 24986642.

- PMID 9564567.

- PMID 9502007.

- PMID 17598943.

- ^ PMID 17578778.

- PMID 7812190.

- ^ "Metronidazole". Drugs.com. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- PMID 21160459. Erratum in: MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011 Jan 14;60(1):18.

- PMID 15489348.

- ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.[page needed]

- S2CID 33823038.

- PMID 19209760.

- PMID 490766.

- PMID 11148007.

- S2CID 44364966.

- PMID 10948104.

- PMID 17218520.

- PMID 10577741.

- S2CID 34154189.

- PMID 18824479.

- PMID 22479659.

- PMID 19332911.

- S2CID 19708165.

- ^ PMID 18663385.

Further reading

- Hernández, Hilda M.; Marcet, Ricardo; Sarracent, Jorge (28 October 2014). "Biological roles of cysteine proteinases in the pathogenesis of Trichomonas vaginalis". Parasite. 21 (54): 54. PMID 25348828.

External links

- TIGR's Trichomonas vaginalis genome sequencing project.

- TrichDB: the Trichomonas vaginalis genome resource

- NIH site on trichomoniasis.

- Taxonomy

- eMedicine article on trichomoniasis.

- Patient UK