Trichothecene

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2008) |

The trichothecenes are a large family of chemically related

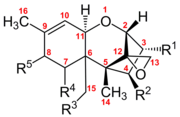

The determining structural features causing the biological activity of trichothecenes are the 12,13-epoxy ring, the presence of hydroxyl or acetyl groups at appropriate positions on the trichothecene nucleus, and the structure and position of the side-chain. They are produced on many different grains such wheat, oats or maize by various Fusarium species including F. graminearum, F. sporotrichioides, F. poae and F. equiseti.

Some molds that produce trichothecene mycotoxins, for example

Classification

General classification

Trichothecenes are a group of over 150 chemically related mycotoxins.[3] Each trichothecene displays a core structure consisting of a single six-membered ring containing a single oxygen atom, flanked by two carbon rings.[4] This core ring structure contains an epoxide, or tricyclic ether, at the 12,13 carbon positions, as well as a double bond at the 9, 10 carbon positions.[5] These two functional groups are primarily responsible for trichothecene ability to inhibit protein synthesis and incur general cytotoxic effects.[6] Notably, this core structure is amphipathic, containing both polar and non polar parts.[7] All trichothecenes are related through this common structure, but each trichothecene also has a unique substitution pattern of oxygen containing functional groups at possible sites on carbons 3,4,7,8, and 15.[5] These functional groups govern the properties of an individual tricothecene and also serve as the basis for the most commonly used classification system for this family of toxins. This classification system breaks up the trichothecene family into four groups: Type A, B, C, and D.

Type A tricothecenes have hydroxyl, ester, or no functional group substitutions around the core ring structure.[4] Common examples of these are Neosolaniol with a hydroxyl substitution at carbon 8, and T-2 toxin with an ester substitution at carbon 8.

Type B tricothecenes are classified by the presence of carbonyl functional groups substituted around the core ring structure.[4] Common examples of these include nivalenol and trichotecin, which both have a ketone functional group at carbon 8.

Type C trichothecenes have an extra carbon 7, carbon 8 epoxide group.[4] The common example of these is crotocin. which also has an ester functional group at carbon 4.

Type D trichothecenes have an additional ring between carbon 4 and carbon 15.[4] These rings can have diverse additional functional groups. Common examples of these are roridin A and satratoxin H.

Although the distinct functional groups of these classification types give each trichothecene unique chemical properties, their classification type does not explicitly indicate their relative toxicity.[4] While Type D trichothecenes are thought to be the most toxic, Types A and B have relatively mixed toxicity.[4]

Alternative classifications

The classification system described above is the most commonly used to group molecules of the trichothecene family. However, a variety of alternative classification systems also exist for these complex molecules. Trichothecenes can also be generally described as simple or macrocyclic.[6] Simple trichothecenes include Types A, B, and C, whereas macrocyclic tricothecenes include Type D and are characterized by the presence of a carbon 4 – carbon 15 bridge. Additionally, J. F. Grove proposed a classification of tricothecenes into three groups that was also based upon the functional substitution patterns of the ring skeleton.[8] Group 1 tricothecenes only have functional groups substituted on the third, fully saturated carbon ring.[8] Group 2 tricothecenes contain additional functional groups on the core ring containing the 9, 10 carbon double bond.[8] Finally, Group 3 trichothecenes contain a ketone functional group at carbon 8; this is the same criteria for Type B trichothecenes.[8]

Advances in the field of evolutionary genetics have also led to the proposal of trichothecene classification systems based on the pathway of their biosynthesis. Genes responsible for the biosynthesis of a mycotoxin are typically located in clusters; in Fusariumi these are known as TRI genes.[9] TRI genes are each responsible for producing an enzyme that carries out a specific step in the biosynthesis of trichothecenes. Mutations in these genes can lead to the production of variant trichothecenes and therefore these molecules could be grouped on the basis of shared biosynthesis steps. For example, a shared step in the biosynthesis of trichothecenes is controlled by the gene TRI4.[10] This enzyme product controls the addition of either three or four oxygens to trichodiene to form either isotrichodiol or isotrichotriol respectively.[10] A variety of trichothecenes can then be synthesized from either of these intermediates and they could therefore be classified as either t-type if synthesized from isotrichotriol or d-type if synthesized from isotrichodiol.[4]

Mechanism of action

The toxicity of tricothecenes is primarily the result of their widely cited action as protein synthesis inhibitors; this inhibition occurs at ribosomes during all three stages of protein synthesis: initiation, elongation, and termination.[11] During initiation, trichothecenes can either inhibit the association of the two ribosomal subunits, or inhibit the function of the mature ribosome by preventing the association of the first tRNA with the start codon.[11] Inhibition at elongation most likely occurs due to trichothecenes preventing the function peptidyl transferase, the enzyme which catalyzes the formation of new peptide bonds on the 60s ribosomal subunit.[12] Inhibition during termination can also be the result of peptidyl transferase inhibition or the ability of trichothecenes to prevent the hydrolysis required at this final step.[11]

It is interesting to note that the substitution pattern of the ring core of trichothecenes influences the toxin's action as either an inhibitor of initiation or as an inhibitor of elongation/termination.[11] Trichothecenes also have the ability to affect general cellular enzyme function due to the tendency of active site thiol groups to attack the 12,13 carbon epoxide ring.[13] These inhibitory effects are seen most dramatically in actively proliferating cells such as in the gastrointestinal tract or the bone marrow.

Protein synthesis occurs in both the cytoplasm of the cell as well as in the luminal space of mitochondria, the cytoplasmic organelle responsible for producing the cell's energy. This is done through an enzymatic pathway that generates highly oxidized molecules called reactive oxygen species, for example hydrogen peroxide.[14] Reactive oxygen species can react with and cause damage to many critical parts of the cell including membranes, proteins, and DNA.[15] Trichothecene inhibition of protein synthesis in the mitochondria allows reactive oxygen species to build up in the cell which inevitably leads to oxidative stress and induction of the programmed cell death pathway, apoptosis.[15]

The induction of apoptosis in cells with high levels of reactive oxygen species is due to a variety of cell signaling pathways. The first is the

Additionally, trichothecenes such as T-2, have also been shown to increase the c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase signaling pathway in cells.[17] Here, c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase is able to increase to phosphorylation of its target, c-Jun, into its active form. Activated c-jun acts as a transcription factor in the cell nucleus for proteins important for facilitating the downstream apoptotic pathway.[17]

Symptomology

The trichothecene mycotoxins are toxic to humans, other mammals, birds, fish, a variety of invertebrates, plants, and eukaryotic cells.[18] The specific toxicity varies depending on the particular toxin and animal species, however the route of administration plays a significantly higher role in determining lethality. The effects of poisoning will depend on the concentration of exposure, length of time and way the person is exposed. A highly concentrated solution or large amount of the gaseous form of the toxin is more likely to cause severe effects, including death. Upon consumption, the toxin inhibits ribosomal protein, DNA and RNA synthesis,[19][18][20] mitochondrial functions[21][22][23] cell division[24][25] while simultaneously activating a cellular stress response named ribotoxic stress response.[26]

The trichothecene mycotoxins can be absorbed though topical, oral and inhalational routes and are highly toxic at the sub-cellular, cellular, and organic system level.[18]

Trichothecenes differ from most other potential weapon toxins since they can act through the skin, which is attributed to their

The response in the body to the mycotoxin, alimentary toxic aleukia, occurs several days after consumption, in four stages:

- The first stage includes inflammation of the gastric and intestinal mucosa.

- The second stage is characterized by granulopenia, and progressive lymphocytosis.

- The third stage is characterized by the appearance of a red rash on the skin of the body, as well as hemorrhage of the skin and mucosa. If severe, aphoniaand death by strangulation can occur.

- By the fourth stage, cells in the lymphoid organs and erythropoiesis in the bone marrow and spleen are depleted and immune response is down.

Infection can be triggered by an injury as minor as a cut, scratch or abrasion.[32]

The following symptoms are exhibited:

- Severe itching and redness of the skin, sores, shedding of the skin

- Distortion of any of the senses, loss of the ability to coordinate muscle movement

- Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea

- Nose and throat pain, discharge from the nose, itching and sneezing

- Cough, difficulty breathing, wheezing, chest pain and spitting up blood

- Temporary bleeding disorders

- Elevated body temperature[33][34]

Regulatory issues

When it comes to animal and human food, type A trichothecenes (e.g.

History

Trichothecenes are believed to have been discovered in 1932 in Orenburg, Russia, during World War II, by the Soviet Union. Around 100,000 people (60% mortality rate) began to suffer and die from alimentary toxic aleukia, a lethal disease with symptoms resembling radiation. It is believed that the Soviet civilians had become ill from ingesting contaminated bread, and inhaling mold through contaminated hay, dusts and ventilation systems. The culprit is believed to be the toxins Fusarium sporotrichioides and Fusarium poae which are high producers of T-2 toxin.[36] Fusarium species are probably the most commonly cited and among the most abundant of the trichothecene-producing fungi.[37]

Trichothecenes make an ideal biologic warfare agent, being lethal and inexpensive to produce in large quantities, stable as an aerosol for dispersion, and without effective vaccination/treatment.[12] Evidence suggests that mycotoxins have already been utilized as biological warfare.

- 1964 there are unconfirmed reports that Egyptian or Russian forces used T-2 with mustard gas

- 1974–1981 "yellow rain" incidents in southeast Asia (Laos, Cambodia) and Afghanistan[38][39][40][41]

- 1975 and 1981 during the Vietnam War, the Soviet Union was alleged to have provided mycotoxins to the armies of Vietnam and Laos for use against resistance forces in Laos and Cambodia[42][43]

- 1979–1989 during the Soviet-Afghan War[44]

- 1985–1989 Iran–Iraq War, reports of mycotoxin shipments to Iraq (in form of powder and smoke)[45]

Since then trichothecenes have been reported throughout the world.[46] They have had a significant economic impact on the world due to loss of human and animal life, increased health care and veterinary care costs, reduced livestock production, disposal of contaminated foods and feeds, and investment in research and applications to reduce severity of the mycotoxin problem. These mycotoxins account for millions of dollars annually in losses, due to factors that are often beyond human control (environmental, ecological, or storage method).[47]

Food contamination

Hazardous concentrations of trichothecenes have been detected in corn, wheat, barley, oats, rice, rye, vegetables, and other crops. Diseases resulting from infection include seed rot, seedling blight, root rot, stalk rot, and ear rot.[48] Trichothecenes are also common contaminants of poultry feeds and their adverse effects on poultry health and productivity have been studied extensively.[49]

Several studies have shown that optimal conditions for fungal growth are not necessarily optimum for toxin production.[50] Toxin production is greatest with high humidity and temperatures of 6–24 °C. The fungal propagation and production is enhanced in tropical conditions with high temperatures and moisture levels; monsoons, flash floods and unseasoned rains during harvest.[51] Trichothecenes have been detected in air samples suggesting that they can be aerosolized on spores or small particles[52][53]

Natural occurrence of TCT has been reported in Asia, Africa, South America, Europe, and North America[54]

- Akakabibyo, a disease of similar etiology, has also been associated with trichothecene contaminated grains in Japan.[55]

- In China, cereals or their products contaminated with trichothecenes including DON, T-2 toxin, and NIV, have also been associated with outbreaks of gastrointestinal disorders.[56]

- In Yugoslavia, studies on mycotoxigenic fungi in raw milk have indicated that 91% of the samples tested were contaminated[57]

- In the US, a study was conducted in seven Midwestern states in 1988–1989 and found mycotoxins in 19.5–24.7% of corn samples.[58] Since the early 1900s, incidences[spelling?] of emesis in animals and humans after consumption of cereals infected with Fusarium species have been described.[59][60]

- In a study in the Bihar region from 1985 to 1987, 51% of the samples tested were contaminated with molds.[61]

- In another study In the Bihar region,[62] high levels were reported in groundnut meal used for dairy cattle.

- In Ludhiana and Punjab researchers found 75% of samples from dairy farms contaminated.[63]

- In India, estimated 10 million dollars were lost due to groundnut contamination with mycotoxins.[64]

Safety

There are no known direct antidotes to trichothecene exposure. Therefore, risk management in contaminated areas is primarily defined by the treatment of exposure symptoms as well as prevention of future exposure.

Treatment

Typical routes of exposure to trichothecene toxins include topical absorption, ingestion, and inhalation. Severity of symptoms depends on the dose and type of exposure, but treatment is primarily focused on supporting bodily systems damaged by the mycotoxin. The first step in most exposure cases is to remove potentially contaminated clothing and to flush the sites of exposure thoroughly with water.[65] This prevents the victim from repeated exposure. Fluids and electrolytes can be given to victims with high levels of gastrointestinal damage to mitigate the effects of reduced tract absorption. Fresh air and assisted respiration can also be administered upon the development of mild respiratory distress.[65] Increasingly severe symptoms can require the application of advanced medical assistance. The onset of leukopenia, or reduction of white blood cell count, can be treated with a plasma or platelet transfusion.[65] Hypotension can be treated with the administration of norepinephrine or dopamine.[65] Development of severe cardiopulmonary distress may require intubation and additional drug treatments to stabilize heart and lung activity.

Additionally, there are a variety of chemicals that can indirectly reduce the damaging effects of trichothecenes on cells and tissues. Activated charcoal solutions are frequently administered to ingestion cases as an adsorbent.[66] Here, the charcoal acts as a porous substance for the toxin to bind, preventing its absorption through the gastrointestinal tract and increasing its removal from the body through bowel excretion. Similar detoxifying adsorbents can also be added to animal feed upon contamination to reduce the bioavailability of the toxin upon consumption. Antioxidants are also useful in mitigating the damaging effects of trichothecenes in response to the increase of reactive oxygen species they produce in cells. Generally, a good diet rich in probiotics, vitamins and nutrients, proteins, and lipidis is thought to be effective in reducing the symptoms of trichothecene poisoning.[16] For example, vitamin E was found to counteract the formation of lipid peroxides induced by T-2 toxin in chickens.[67] Similarly, cosupplementation of modified glucomannans and selenium in the diets of chickens also consuming T-2 toxin, reduced the deleterious effects of toxin associated depletion of antioxidants in the liver. Despite not being a direct antidote, these antioxidants may be critical in reducing the severity of trichothecene exposures.

Prevention

Trichothecenes are mycotoxins produced by molds that frequently contaminate stores of grain products. This makes trichothecene contamination a significant public health problem, and many areas have strict limits on permitted trichothecene content. For example, in the European Union, only .025 ppm of T-2 toxin is permissible in bakery products intended for human consumption.[68] The molds that can produce trichothecenes grow well in dark, temperate places with high moisture content. Therefore, one of the best ways to prevent trichothecene contamination in food products is to store the resources in the proper conditions to prevent the growth of molds.[16] For example, it is generally advised to only store grains in areas with a moisture content of less than 15%.[69] However, if an area has already been contaminated with trichothecene toxins, there are a variety of possible decontamination strategies to prevent further exposure. Treatment with 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) in 0.1M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) for 4–5 hours has been shown to inhibit the biological activity of T-2 toxin.[16] Incubation with aqueous ozone at approximately 25 ppm has also been shown to degrade a variety of trichothecenes through a mechanism involving oxidation of the 9, 10 carbon double bond.[70] UV exposure has also been shown to be effective under the right conditions.[16]

Outside of the strategies for physical and chemical decontamination, advancing research in molecular genetics has also given rise to the potential of a biological decontamination approach. Many microbes, including bacteria, yeast, and fungi, have evolved enzymatic gene products which facilitate the specific and efficient degradation of trichothecene mycotoxins.[69] Many of these enzymes specifically degrade the 12,13 carbon epoxide ring which is important for the toxicity of trichothecenes. For example, the Eubacteria strain BBSH 797 produces de-epoxidase enzymes which reduce the 12,13 carbon epoxide ring to a double bond group.[69] These, along with other microbes expressing trichothecene detoxifying properties, can be used in feed stores to prevent to toxic effect of contaminated feed upon consumption.[16] Furthermore, molecular cloning of the genes responsible for producing these detoxifying enzymes could be useful in producing strains of agricultural products that are resistant to trichothecene poisoning.[16]

Epoxitrichothecenes

Epoxitrichothecenes are a variation of the above, and were once explored for military use in East Germany, and possibly the whole Soviet bloc.[71] There is no feasible treatment once symptoms of epoxithichothecene poisoning set in, though the effects can subside without leaving any permanent damage.

The plans for use as a large-scale bioweapon were dropped, as the relevant epoxitrichothecenes degrade very quickly under UV light and heat, as well as chlorine exposure, making them useless for open attacks and the poisoning of water supplies.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Detection of Airborne Stachybotrys chartarum Macrocyclic Trichothecene Mycotoxins in the Indoor Environment

- PMID 11798344.

- ^ "American Phytopathological Society". American Phytopathological Society. Archived from the original on 2018-05-07. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ PMID 22069741.

- ^ ISBN 9780309034302.

- ^ PMID 12857779.

- ^ PMID 2783163.

- ^ PMID 3062504.

- S2CID 19787988.

- ^ PMID 16917519.

- ^ S2CID 94777285.

- ^ PMID 15207307.

- PMID 1212759.

- PMID 24987008.

- ^ S2CID 17446994.

- ^ PMID 28430618.

- ^ PMID 18535001.

- ^ ISBN 978-9997320919.

- ^ a b McLaughlin C, Vaughan M, Campbell I, Wei CM, Stafford M, Hansen B (1977). "Inhibition of protein synthesis by trichothecenes.". Mycotoxins in human and animal health. Park Forest South, IL: Pathotox Publishers. pp. 263–75.

- PMID 8246841.

- PMID 7017711.

- PMID 19541794.

- PMID 22295173.

- PMID 7597700.

- PMID 3824405.

- PMID 10318810.

- PMID 4521056.

- PMID 856003.

- PMID 3158480.

- PMID 3347933.

- PMID 8463495.

- ^ Schwarzer K (2009). "Harmful effects of mycotoxins on animal physiology". 17th Annual ASAIM SEA Feed Technology and Nutrition Workshop. Hue, Vietnam.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Trichothecene Mycotoxin | IDPH". www.dph.illinois.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- PMID 6609858.

- ^ Miller JD (2003). "Aspects of the ecology of fusarium toxins in cereals.". In de Vries JW, Trucksess MW, Jakson LS (eds.). Mycotoxins and Food Safety. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 19–27.

- ^ Joffe AZ (1950). Toxicity of fungi on cereals overwintered in the field: on the etiology of alimentary toxic aleukia (Ph.D.). Leningrad: Inst. Bot. Acad. Sci. p. 205.

- S2CID 1534222.

- PMID 6535464.

- PMID 6643363.

- PMID 6636506.

- ^ Wannemacher JR, Wiener SL. "Chapter 34,: Trichothecene Mycotoxins". In Sidell FR, Takafuji ET, Franz DR (eds.). Medical Aspects Of Chemical And Biological Warfare. Textbook of Military Medicine series. Office of The Surgeon General, Department of the Army, United States of America.

- ^ Haig AM (March 22, 1982). Special Report 98: Chemical Warfare in Southeast Asia and Afghanistan: Report to the Congress from Secretary of State Haig (Report). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- S2CID 22473397.

- ^ "World Affairs Vol. 145, No. 3, Afghanistan".

- ^ "CNS - Obtain Microbial Seed Stock for Standard or Novel Agent". webarchive.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 2001-11-27. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- PMID 18220574.

- ISSN 1319-6103.

- PMID 23162697.

- ^ Leeson S, Dias GJ, Summers JD (1995). "Tricothecenes". Poultry Metabolic Disorders. Guelph, Ontario, Canada. pp. 190–226.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hesseltine CW, Shotwell OL, Smith M, Ellis JJ, Vandegraft E, Shannon G (1970). "Production of various aflatoxins by strains of the Aspergillis flavus series.". Proc. first US–Japan Conf. Toxic Microorg. Washington.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dudeja P, Gupta RK, Minhas AS (eds.). Food Safety in the 21st Century: Public Health Perspective.

- PMID 15640178.

- .

- ^ Beasley VR, ed. (1989). Tricothecene Mycotoxicosis: Pathophysiologic Effects. Vol. 1. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 1–26.

- PMID 4538152.

- ^ Lou XY (1988). "Fusarium toxins contamination of cereals in China". Proc. Japanese Assoc. Mycotoxicology. Suppl. 1: 97–98.

- ^ Skrinjar M, Danev M, Dimic G (1995). "Investigation on the presence of toxigenic fungi and aflatoxins in raw milk". Acta Aliment. 24: 395–402.

- PMID 1825995.

- ^ Naumov NA (1916). "Intoxicating bread". Min. Yeml. (Russia), Trudy Ruiri Miwel. I. Fitopatol. Uchen, Kom.: 216.

- ^ Dounin M (1930). "The fusariosis of cereal crops in European-Russia in 1923". Phytopathol. 16: 305–308.

- .

- S2CID 32084324.

- ^ Dhand NK, Joshi DB, Jand SK (1998). "Aflatoxins in dairy feeds/ingredients". Ind. J. Anim. Nutr. 15: 285–286.

- PMID 9863277.

- ^ a b c d "T-2 TOXIN – National Library of Medicine HSDB Database". toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- PMID 9276881.

- PMID 9000276.

- PMID 25734690.

- ^ .

- PMID 16185803.

- ^ Die Chemie der Kampfstoffe, GDR Government publishing, 1988