Audio playback is not supported in your browser. You can

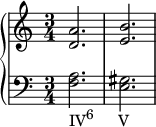

dominant chord

in measure three. Chailley did once write:

Tristan' s chromaticism , grounded in appoggiaturas and passing notes, technically and spiritually represents an apogee of tension . I have never been able to understand how the preposterous idea that Tristan could be made the prototype of an atonality grounded in destruction of all tension could possibly have gained credence. This was an idea that was disseminated under the (hardly disinterested) authority of Schoenberg , to the point where Alban Berg could cite the Tristan Chord in the Lyric Suite

Fred Lerdahl presents alternate interpretations of the Tristan motive, as either i ii♯ ♯ ♯ ♯ altered pre-dominant : F–B–D♯ ♯ ♯

Nonfunctional analyses Nonfunctional analyses are based on structure (rather than function), and are characterized as vertical characterizations or linear analyses.

Vertical characterizations include interpreting the chord's root as on the seventh degree (VII), of F♯ [29] [30]

Linear analyses include that of Noske

William Mitchell, viewing the Tristan chord from a Schenkerian perspective, does not see the G♯

passing note. This

ascent by

minor third is mirrored by the descending line (F–E–D

♯ –D), a

descent by minor third, making the D

♯ , like A

♯ , an appoggiatura. This makes the chord a

diminished seventh chord (G

♯ –B–D–F).

Serge Gut argues that, "if one focuses essentially on melodic motion, one sees how its dynamic force creates a sense of an appoggiatura each time, that is, at the beginning of each measure, creating a mood both feverish and tense ... thus in the soprano motif, the G♯ ♯ ♯ minor chord with an added sixth (D–F–A–B) on the fourth degree (IV), though it is engendered by melodic waves.

Allen first identifies the chord as an atonal set, 4–27 (half-diminished seventh chord ), then "elect[s] to place that consideration in a secondary, even tertiary position compared to the most dynamic aspect of the opening music, which is clearly the large-scale ascending motion that develops in the upper voice, in its entirety a linear projection of the Tristan Chord transposed to level three, g♯ ♯

Schoenberg describes it as a "wandering chord [vagierender Akkord]... it can come from anywhere".

Mayrberger's opinion After summarizing the above analyses Nattiez asserts that the context of the Tristan chord is A minor, and that analyses which say the key is E major or E♭ wrong ". He privileges analyses of the chord as on the second degree (II). He then supplies a Wagner-approved analysis, that of Czech professor Carl Mayrberger[36] ♯ appoggiatura . But above all, Mayrberger considers the attraction between the E and the real bass F to be paramount, and calls the Tristan chord a Zwitterakkord (an ambiguous, hybrid, or possibly bisexual or androgynous, chord), whose F is controlled by the key of A minor, and D♯

Responses and influences The chord and the figure surrounding it is well enough known to have been parodied and quoted by a number of later musicians. Debussy includes the chord in a setting of the phrase je suis triste in his opera Pelléas et Mélisande Children's Corner Benjamin Britten slyly invokes it at the moment in Albert Herring Paul Lansky based the harmonic content of his first electronic piece, mild und leise (1973), on the Tristan chord. This piece is best known from being sampled in the Radiohead song "Idioteque ".

Bernard Herrmann incorporated the chord in his scores for Vertigo Tender is the Night [citation needed

Christian Thielemann , the music director of the Bayreuth Festival from 2015-20, discussed the Tristan chord in his book, My Life with Wagner : the chord "is the password, the cipher for all modern music. It is a chord that does not conform to any key, a chord on the verge of dissonance", and "The Tristan chord does not seek to be resolved in the closest consonance, as the classic theory of harmony requires; [it] is sufficient unto itself, just as Tristan and Isolde are sufficient unto themselves and know only their love."[42]

More recently, American composer and humorist

Flavio Chamis wrote

Tristan Blues , a composition based on the Tristan chord. The work, for harmonica and piano was recorded on the CD

Especiaria , released in Brazil by the Biscoito Fino label. Additionally, New York-based composer

Dalit Warshaw 's narrative concerto for piano and orchestra,

Conjuring Tristan , employs the Tristan chord in exploring the themes of

Thomas Mann 's novella

Tristan through Wagner's music.

[45] The prelude of Wagner's opera is prominently used in the film Melancholia Lars von Trier .

See also References

^ Vogel 1962 , p. 12, cited in Nattiez 1990 , p. 219^ Gołąb 1987 , [page needed .^ Benward and Saker 2008 , p. 233.^ D'Indy 1903 , [page needed .^ Lorenz 1924–33 , [page needed .^ Deliège 1979 , [page needed .^ Gut 1981 , [page needed .^ Goldman 1965 , [page needed .^ Schoenberg 1954 , [page needed .^ Arend 1901 , [page needed .^ Ergo 1912 , [page needed .^ Kurth 1920 , [page needed .^ Distler 1940 , [page needed .^ D'Indy 1903 , p. 117, cited in Nattiez 1990 , p. 224^ Gut 1981 , p. 149, cited in Nattiez (1990 , p. 220)^ Kistler 1879 , [page needed .^ Jadassohn 1899 , [page needed .^ cf. Schenker 1925–30 , 2: p. 29

^ Mayrberger 1878 , [page needed .. ^ Ross, Alex (2013-05-19). "A Wagner Birthday Roast" . The New Yorker . Retrieved 2022-07-16 .^ Kaczmarczyk, Jeffrey (2015-01-31). "Many lovely moments in Grand Rapids Symphony's evening of music by Wagner" . mlive . Retrieved 2023-03-06 .

Sources

Anon. 2006. "Especiaria CD: Flávio Chamis ". Biscoito Fino website (archive from 24 August 2011, accessed 16 May 2014). Arend, M. (1901). "Harmonische Analyse des Tristan-Vorspiels", Bayreuther Blätter . No. 24: 160–169. Cited in Nattiez 1990 , p. 223. Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2008). Music in Theory and Practice , vol. 2. Boston: McGraw-Hill. Chailley, Jacques (1963). Tristan et Isolde de Richard Wagner . 2 vols. Les Cours de Sorbonne. Paris: Centre de Documentation Universitaire. Deliège, Célestin (1979)[full citation needed D'Indy, Vincent (1903). Cours de composition musicale , vol. 1. Paris: Durand. Distler, Hugo (1940). Funktionelle Harmonielehre . Basel: Bärenreiter-Verlag.Dommel-Diény, Amy . 1965. Douze dialogues d'initiation à l'harmonie classique; suivis de quelques notions de solfège , preface by Louis Martin. Paris: Les Editions Ouvrières.Ergo, E. (1912). "Über Wagners Harmonik und Melodik". Bayreuther Blätter , no. 35:34–41. Erickson, Robert (1975). Sound Structure in Music . Oakland, California: University of California Press. . Forte, Allen (1988). New Approaches to the Linear Analysis of Music. Journal of the American Musicological Society Gołąb, Maciej. 1987. "O 'akordzie tristanowskim' u Chopina". Rocznik Chopinowski 19:189–98. German version, as "Über den Tristan-Akkord bei Chopin". Chopin Studies 3 (1990): 246–256. English version, as "On the Tristan Chord", in: M. Gołąb, Twelve Studies in Chopin , Frankfurt am Main 2014: 81-92 Goldman, Richard Franko (1965). Harmony in Western Music Grimshaw, Jeremy. "mild und leise, computer synthesized tape" . AllMusic . Retrieved 2019-02-19 . . Gut, Serge (1981). "Encore et toujours: 'L'accord de Tristan'", L'avant-scène Opéra , nos. 34–35 ("Tristan et Isole"): 148–151.Howard, Patricia (1969), The Operas of Benjamin Britten: An Introduction , New York and Washington: Frederick A. Praeger, Publishers Huebner, Steven (1999). French Opera at the Fin de Siècle: Wagnerism, Nationalism, and Style . Oxford: Oxford University Press. . Jadassohn, Josef . 1899. L'organisation actuelle de la surveillance médicale de la prostitution est-elle susceptible d'amélioration? Brussels: [s.n.].Kistler, Cyrill (1879), Harmonielehre für Lehrer und Lernende, Opus 44 , Munich: W. Schmid Kurth, Ernst . 1920. Romantische Harmonik und ihre Krise in Wagners "Tristan" . Lorenz, Alfred Ottokar. 1924–33. Das Geheimnis der Form bei Richard Wagner , in 4 volumes. Berlin: M. Hesse. Reprinted, Tutzing: H. Schneider, 1966. Mayrberger, Carl. 1878. Lehrbuch der musikalischen Harmonik in gemeinfasslicher Darstellung, für höhere Musikschulen und Lehrerseminarien, sowie zum Selbstunterrichte. Part 1: "Die diatonische Harmonik in Dur". Pressburg: Gustav Heckenast. . Noske, Frits R. (1981). "Melodic Determinants in Tonal Structures". Muzikoloski zbornik Ljubljana / Ljubljana Musicological Annual 17, no. 1:111–121. Page, Tim (23 December 2011). "Filmmaker's Audacious Teaming of His 'Melancholia' with Wagner's Music ". The Washington Post . Sadai, Yizhak (1980). Harmony in Its Systemic and Phenomenological Aspects , translated by J. Davis and M. Shlesinger. Jerusalem: Yanetz. Schenker, Heinrich (1925–30). Das Meisterwerk in der Musik , 3 vols. Munich: Drei Masken Verlag. English translation, as The Masterwork in Music: A Yearbook , edited by William Drabkin, translated by Ian Bent, Alfred Clayton, William Drabkin, Richard Kramer, Derrick Puffett, John Rothgeb, and Hedi Siegel. Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis 4. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994–1997.Schoenberg, Arnold (1911). Harmonielehre . Leipzig and Vienna: Verlagseigentum der Universal-Edition.Schoenberg, Arnold (1954). Die formbildenden Tendenzen der Harmonie , translated by Erwin Stein. Mainz: B. Schott's Sohne. Schoenberg, Arnold (1969). "Structural Functions of Harmony", revised edition. New York: W. W. Norton. Library of Congress – 74-81181. Vogel, Martin (1962). Der Tristan-Akkord und die Krise der modernen Harmonielehre . Orpheus-Schriftenreihe zu Grundfragen der Musik 2. Düsseldorf:[full citation needed Titled in response to Kurth (1920). . Ward, William R. (1970). Examples for the Study of Musical Style

Further reading

Bailey, Robert (1986). Prelude and Transfiguration from Tristan and Isolde (Norton Critical Scores). New York: W. W. Norton.

Ellis, Mark (2010). A Chord in Time: The Evolution of the Augmented Sixth from Monteverdi to Mahler . Farnham: Ashgate.

Jadassohn, Salomon . 1899a. Erläuterungen der in Joh. Seb. Bach's Kunst der Fuge enthaltenen Fugen und Kanons . Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. English as, An Analysis of the Fugues and Canons Contained in Joh. Seb. Bach's "Art of fugue" . Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1899.Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899b. A Manual of Harmony . New York: G. Schirmer.

Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899c. Ratschläge und Hinweise für die Instrumentationsstudien der Anfänger . Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899d. Das Wesen der Melodie in der Tonkunst . Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. Das Tonbewusstsein: die Lehre vom musikalischen Hören . English as, A Practical Course in Ear Training; or, a Guide for Acquiring Relative and Absolute Pitch , translated from the German by Le Roy B. Campbell. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1899.

Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899e. Zur Einführung in J.S. Bach's Passions-Musik nach dem Evangelisten Matthaeus . Berlin: Harmonie.

Magee, Bryan (2002). The Tristan Chord: Wagner and Philosophy Mayrberger, Carl. 1994 [1881]. "Die Harmonik Richard Wagner’s an den Leitmotiven aus Tristan und Isolde (1881)", translated and annotated by .

. Riemann, Hugo . 1872. "Über Tonalität". Neue Zeitschrift für Musik Riemann, Hugo. 1875. Die Hülfsmittel der Modulation: Studie von Dr. Hugo Riemann . Kassel: F. Luckhardt.

Riemann, Hugo. 1877. Musikalische Syntaxis: Grundriss einer harmonischen Satzbildungslehre , revised edition. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

Riemann, Hugo. 1882. "Die Natur der Harmonik". In Sammlung musikalischer Vorträge 40, revised edition, edited by P. Graf Waldersee, 4:157–190. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. English translation, as "The Nature of Harmony", by John Comfort Fillmore, in his New Lessons in Harmony , 3–32. Philadelphia: Theodore Presser, 1887.

Riemann, Hugo. 1883a. Elementar-Musiklehre . Hamburg: K. Grädener & J. F. Richter.

Riemann, Hugo. 1883b. Neue Schule der Melodik: Entwurf einer Lehre des Kontrapunkts nach einer neuen Methode . Hamburg: K. Grädener & J. F. Richter.

Riemann, Hugo. 1887. Systematische Modulationslehre als Grundlage der musikalischen Formenlehre . Hamburg: J. F. Richter.

Riemann, Hugo. 1893. Opern-Handbuch , second edition, with a supplement by F. Stieger. Leipzig: Koch.

Riemann, Hugo. 1895. Präludien und Studien: gesammelte Aufsätze zur Ästhetik, Theorie und Geschichte der Musik , revised edition, vol. 1. Frankfurt: Bechhold.

Riemann, Hugo. 1900. Präludien und Studien: gesammelte Aufsätze zur Ästhetik, Theorie und Geschichte der Musik , revised edition, vol. 2. Leipzig: Seemann.

Riemann, Hugo. 1901a. Präludien und Studien: gesammelte Aufsätze zur Ästhetik, Theorie und Geschichte der Musik , vol. 3,. Leipzig: Seemann. Reprint (3 vols. in 1), Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1967. Reprint (3 vols. in 2), Nendeln/Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1976.

Riemann, Hugo. 1901b. Geschichte der Musik seit Beethoven (1800–1900) . Berlin and Stuttgart: W. Spemann

Riemann, Hugo. 1903. Vereinfachte Harmonielehre oder die Lehre von den tonalen Funktionen der Akkorde , second edition. London: Augener; New York: G. Schirmer.

Riemann, Hugo. 1905. "Das Problem des harmonischen Dualismus". Neue Zeitschrift für Musik

Riemann, Hugo. 1902–13. Grosse Kompositionslehre , revised edition, 3 vols. Berlin and Stuttgart: W. Spemann.

Riemann, Hugo. 1914–15. "Ideen zu einer 'Lehre von den Tonvorstellungen'", Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters 1914–15 , 1–26. Reprinted in Musikhören , edited by B. Dopheide, 14–47. Darmstadt: [s.n.?], 1975. English translation by ? in Journal of Music Theory

Riemann, Hugo. 1916. "Neue Beiträge zu einer Lehre von den Tonvorstellungen". Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters 1916 : 1–21.

Riemann, Hugo. 1919. Elementar-Schulbuch der Harmonielehre , third edition. Berlin: Max Hesse.

Riemann, Hugo. 1921. Geschichte der Musiktheorie im 9.–19. Jahrhundert , revised edition, 3 vols. Brlin: Max Hesse. Reprinted, Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1990.

Riemann, Hugo. 1922. Allgemeine Musiklehre: Handbuch der Musik , 9th edition. Max Hesses Handbücher 5. Berlin: Max Hesse.

Riemann, Hugo. 1929. Handbuch der Harmonielehre , 10th edition, formerly titled Katechismus der Harmonie- und Modulationslehre and Skizze einer neuen Methode der Harmonielehre . Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

Schering, Arnold (1935). "Musikalische Symbolkunde". Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek :15–36.Stegemann, Benedikt (2013). Theory of Tonality . Theoretical Studies. Wilhelmshaven: Noetzel.

Wolzogen, Hans von (1883). Erinnerungen an Richard Wagner: ein Vortrag, gehalten am 13. April 1883 im Wissenschaftlichen Club zu Wien . Vienna: C. Konegen.Wolzogen, Hans von (1888). Wagneriana. Gesammelte Aufsätze über R. Wagner's Werke, vom Ring bis zum Gral. Eine Gedenkgabe für alte und neue Festspielgäste zum Jahre 1888 . Leipzig: F. Freund. Wolzogen, Hans von (1891). Erinnerungen an Richard Wagner Wolzogen, Hans von, ed. (1904). Wagner-Brevier . Die Musik, Sammlung illustrierter Einzeldarstellungen 3. Berlin: Bard und Marquardt. Wolzogen, Hans von (1906a). Musikalisch-dramatische Parallelen: Beiträge zur Erkenntnis von der Musik als Ausdruck Wolzogen, Hans von (1906b). "Einführung". In Heinrich Porges, Tristan und Isolde , with an introduction by Hans von Wolzogen. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

Wolzogen, Hans von (1907). "Einführung". In Richard Wagner, Entwürfe zu: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Tristan und Isolde, Parsifal , edited by Hans von Wolzogen. Leipzig: C. F. W. Siegel.

Wolzogen, Hans von (1908). Aus Richard Wagners Geisteswelt: neue Wagneriana und Verwandtes . Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler. Wolzogen, Hans von (1924). Wagner und seine Werke, ausgewählte Aufsätze . Deutsche Musikbücherei. Vol. 32. Regensburg: Gustav Bosse Verlag. Wolzogen, Hans von (1929). Musik und Theater . Von deutscher Musik. Vol. 37. Regensburg: Gustav Bosse.

Characters Medieval sources Later literature Music Film

Art

Complete operas

Non-operatic music Writings Other opera

Bayreuth Festival Wagner family

Cultural depictions

Named for Wagner Related