Tryptophan

Skeletal formula of L-tryptophan

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Tryptophan

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2S)-2-amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid | |||

| Other names

2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.000.723 | ||

IUPHAR/BPS |

|||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C11H12N2O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 204.229 g·mol−1 | ||

| Soluble: 0.23 g/L at 0 °C, 11.4 g/L at 25 °C, | |||

| Solubility | Soluble in hot alcohol, alkali hydroxides; insoluble in chloroform. | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.38 (carboxyl), 9.39 (amino)[2] | ||

| -132.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Pharmacology | |||

| N06AX02 (WHO) | |||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Tryptophan (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)[3] is an α-

Like other amino acids, tryptophan is a

Humans and many animals cannot synthesize tryptophan: they need to obtain it through their diet, making it an

Tryptophan is named after the digestive enzymes

Function

Amino acids, including tryptophan, are used as building blocks in

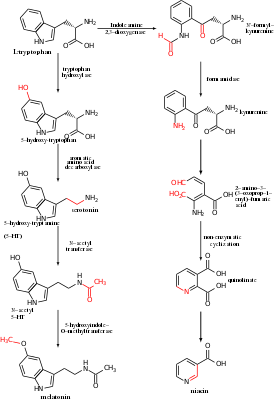

- Serotonin (a neurotransmitter), synthesized by tryptophan hydroxylase.[9][10]

- 5-hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase enzymes.[11]

- Kynurenine, to which tryptophan is mainly (more than 95%) metabolized. Two enzymes, namely indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in the immune system and the brain, and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) in the liver, are responsible for the synthesis of kynurenine from tryptophan. The kynurenine pathway of tryptophan catabolism is altered in several diseases, including psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia,[12] major depressive disorder,[12] and bipolar disorder.[12][13]

- Niacin, also known as vitamin B3, is synthesized from tryptophan via kynurenine and quinolinic acids.[14]

- phytohormones) are synthesized from tryptophan.[15]

The disorder fructose malabsorption causes improper absorption of tryptophan in the intestine, reduced levels of tryptophan in the blood,[16] and depression.[17]

In bacteria that synthesize tryptophan, high cellular levels of this amino acid activate a

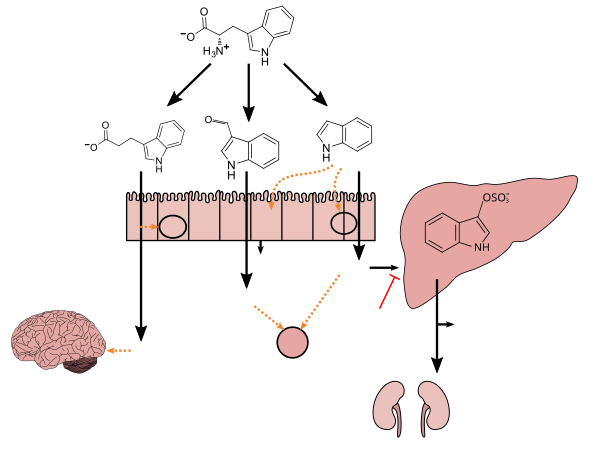

Tryptophan metabolism by

human gastrointestinal microbiota ( )activated charcoal), an intestinal sorbent that is taken by mouth, adsorbs indole, in turn decreasing the concentration of indoxyl sulfate in blood plasma.[19] |

Recommended dietary allowance

In 2002, the

Dietary sources

Tryptophan is present in most protein-based foods or dietary proteins. It is particularly plentiful in

| Food | Tryptophan [g/100 g of food] |

Protein [g/100 g of food] |

Tryptophan/protein [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg white, dried | 1.00 | 81.10 | 1.23 |

| Spirulina, dried | 0.92 | 57.47 | 1.62 |

| Cod, Atlantic, dried | 0.70 | 62.82 | 1.11 |

Soybeans , raw |

0.59 | 36.49 | 1.62 |

| Cheese, Parmesan |

0.56 | 37.90 | 1.47 |

| Chia seeds, dried | 0.44 | 16.50 | 2.64 |

Sesame seed |

0.37 | 17.00 | 2.17 |

| Hemp seed, hulled | 0.37 | 31.56 | 1.17 |

| Cheese, Cheddar | 0.32 | 24.90 | 1.29 |

| Sunflower seed | 0.30 | 17.20 | 1.74 |

| Pork, chop | 0.25 | 19.27 | 1.27 |

| Turkey | 0.24 | 21.89 | 1.11 |

Chicken |

0.24 | 20.85 | 1.14 |

| Beef | 0.23 | 20.13 | 1.12 |

| Oats | 0.23 | 16.89 | 1.39 |

| Salmon | 0.22 | 19.84 | 1.12 |

| Lamb, chop | 0.21 | 18.33 | 1.17 |

| Perch, Atlantic | 0.21 | 18.62 | 1.12 |

| Chickpeas, raw | 0.19 | 19.30 | 0.96 |

Egg |

0.17 | 12.58 | 1.33 |

| Wheat flour, white | 0.13 | 10.33 | 1.23 |

| Baking chocolate, unsweetened | 0.13 | 12.90 | 1.23 |

| Milk | 0.08 | 3.22 | 2.34 |

| Rice, white, medium-grain, cooked | 0.03 | 2.38 | 1.18 |

| Quinoa, uncooked | 0.17 | 14.12 | 1.20 |

| Quinoa, cooked | 0.05 | 4.40 | 1.10 |

| Potatoes, russet | 0.02 | 2.14 | 0.84 |

| Tamarind | 0.02 | 2.80 | 0.64 |

| Banana | 0.01 | 1.03 | 0.87 |

Medical use

Depression

Because tryptophan is converted into

In 2001 a

Insomnia

The

Side effects

Potential

Interactions

Tryptophan taken as a dietary supplement (such as in tablet form) has the potential to cause serotonin syndrome when combined with antidepressants of the MAOI or SSRI class or other strongly serotonergic drugs.[35] Because tryptophan supplementation has not been thoroughly studied in a clinical setting, its interactions with other drugs are not well known.[31]

Isolation

The isolation of tryptophan was first reported by

Biosynthesis and industrial production

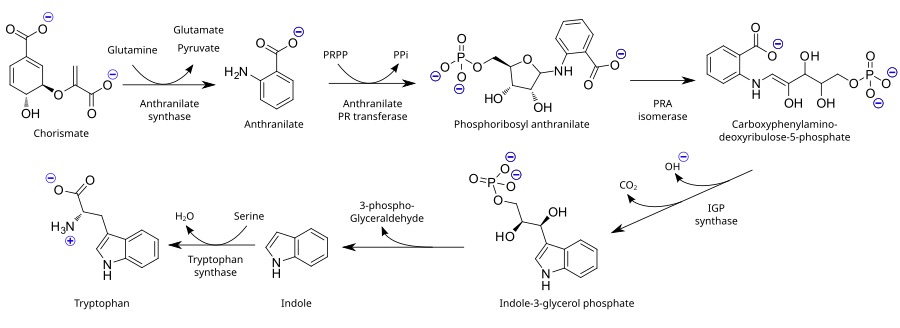

As an essential amino acid, tryptophan is not synthesized from simpler substances in humans and other animals, so it needs to be present in the diet in the form of tryptophan-containing proteins. Plants and

The industrial production of tryptophan is also

Society and culture

Showa Denko contamination scandal

There was a large

Subsequent studies suggested that EMS was linked to specific batches of L-tryptophan supplied by a single large Japanese manufacturer,

The FDA loosened its restrictions on sales and marketing of tryptophan in February 2001,[43] but continued to limit the importation of tryptophan not intended for an exempted use until 2005.[55]

The fact that the Showa Denko facility used

Turkey meat and drowsiness hypothesis

A common assertion in the US and the UK

Research

In 1912

Tryptophan affects brain serotonin synthesis when given orally in a purified form and is used to modify serotonin levels for research.[30] Low brain serotonin level is induced by administration of tryptophan-poor protein in a technique called acute tryptophan depletion.[69] Studies using this method have evaluated the effect of serotonin on mood and social behavior, finding that serotonin reduces aggression and increases agreeableness.[70]

Fluorescence

Tryptophan is an important intrinsic fluorescent probe (amino acid), which can be used to estimate the nature of the microenvironment around the tryptophan residue. Most of the intrinsic fluorescence emissions of a folded protein are due to excitation of tryptophan residues.

See also

- 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP)

- Acree–Rosenheim reaction

- Adamkiewicz reaction

- Attenuator (genetics)

- N,N-Dimethyltryptamine

- Hopkins–Cole reaction

- Serotonin

- Tryptamine

References

- ^ PMID 22992800.

- ISBN 0-19-855338-2.

- ^ "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. 1983. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- S2CID 7820568.

- ^ "L-tryptophan | C11H12N2O2 - PubChem". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- .

- ISBN 978-3-11-085465-7, retrieved 19 February 2024

- .

- PMID 6132421.

- S2CID 8451316. Archived from the original(PDF) on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ PMID 4391290. Archived from the original(PDF) on 31 May 2014.

- ^ S2CID 227132820.

- S2CID 224314102.

- PMID 14284754.

- S2CID 9949830.

- PMID 11336160. Archived from the original(PDF) on 19 April 2016.

- PMID 9620891.

- PMID 16285852.

- ^ PMID 27102537.

Lactobacillus spp. convert tryptophan to indole-3-aldehyde (I3A) through unidentified enzymes [125]. Clostridium sporogenes convert tryptophan to IPA [6], likely via a tryptophan deaminase. ... IPA also potently scavenges hydroxyl radicals

Table 2: Microbial metabolites: their synthesis, mechanisms of action, and effects on health and disease

Figure 1: Molecular mechanisms of action of indole and its metabolites on host physiology and disease - PMID 19234110.

Production of IPA was shown to be completely dependent on the presence of gut microflora and could be established by colonization with the bacterium Clostridium sporogenes.

IPA metabolism diagram - ^ "3-Indolepropionic acid". Human Metabolome Database. University of Alberta. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- S2CID 6630247.

[Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA)] has previously been identified in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of humans, but its functions are not known. ... In kinetic competition experiments using free radical-trapping agents, the capacity of IPA to scavenge hydroxyl radicals exceeded that of melatonin, an indoleamine considered to be the most potent naturally occurring scavenger of free radicals. In contrast with other antioxidants, IPA was not converted to reactive intermediates with pro-oxidant activity.

- ISBN 978-0-309-08525-0.

- ^ a b Ballantyne C (21 November 2007). "Does Turkey Make You Sleepy?". Scientific American. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ a b McCue K. "Chemistry.org: Thanksgiving, Turkey, and Tryptophan". Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ^ a b c Holden J. "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 22". Nutrient Data Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ Rambali B, Van Andel I, Schenk E, Wolterink G, van de Werken G, Stevenson H, Vleeming W (2002). "[The contribution of cocoa additive to cigarette smoking addiction]" (PDF). RIVM (report 650270002/2002). The National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (Netherlands). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2005.

- S2CID 145779393.

- PMID 23077193.

- ^ PMID 6115400.

- ^ PMID 11869656.

- PMID 23769610.

- PMID 27998379.

- PMID 23077196.

- ^ PMID 22589230.

- PMID 16992614.

- .

- PMID 7640526.

- PMID 12523387.

- PMID 22138494.

- PMID 18725290.

- ISBN 978-0-12-386455-0.

- ^ a b c d "Information Paper on L-tryptophan and 5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan". FU. S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Nutritional Products, Labeling, and Dietary Supplements. 1 February 2001. Archived from the original on 25 February 2005. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ "L-tryptophan: Uses and Risks". WebMD. 12 May 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ Altman LK (27 April 1990). "Studies Tie Disorder to Maker of Food Supplement". The New York Times.

- PMID 1754978.

- ^ "COT Statement on Tryptophan and the Eosinophilia-Myalgia Syndrome" (PDF). UK Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment. June 2004.

- PMID 2355442.

- PMID 8496862.

- PMID 8895184.

- PMID 2270484.

- PMID 1544609.

- S2CID 7785345.

- ^ Michael Predator Carlton. "Molecular Biology and Genetic Engineering explained by someone who's done it". Archived from the original on 24 June 2007.

- PMID 21702023.

- PMID 7765187.

- PMID 2237411.

- ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "Food & mood. (neuroscience professor Richard Wurtman) (Interview)". Nutrition Action Healthletter. September 1992.[dead link]

- ^ PMID 3279747.

- ^ PMID 12499331.

- ^ PMID 17284739.

- ^ PMID 22820012.

- PMID 1148286.

- PMID 6538743.

- ^ S2CID 14345137.

- ^ Atul Khullar MD (10 July 2012). "The Role of Melatonin in the Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Cycle". Psychiatric Times Vol 29 No 7. 29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - .

- PMID 23428157.

- PMID 23440461.

Further reading

- Wood RM, Rilling JK, Sanfey AG, Bhagwagar Z, Rogers RD (May 2006). "Effects of tryptophan depletion on the performance of an iterated Prisoner's Dilemma game in healthy adults". Neuropsychopharmacology. 31 (5): 1075–84. PMID 16407905.

External links

- "KEGG PATHWAY: Tryptophan metabolism - Homo sapiens". KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. 23 August 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- G. P. Moss. "Tryptophan Catabolism (early stages)". Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (NC-IUBMB). Archived from the original on 13 September 2003. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- G. P. Moss. "Tryptophan Catabolism (later stages)". Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (NC-IUBMB). Archived from the original on 13 September 2003. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- B. Mikkelson, D. P. Mikkelson (22 November 2007). "Turkey Causes Sleepiness". Urban Legends Reference Pages. Snopes.com. Retrieved 20 April 2008.