Ottoman miniature

| Culture of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Visual arts |

| Performing arts |

| Languages and literature |

| Sports |

| Other |

Ottoman miniature (

While Ottoman miniatures have been very much inspired by Persian miniatures, Ottoman artisans developed a unique style that separated themselves from their Persian influences[3]. Ottoman miniatures are known specifically for their factual accounts of things such as military events, whereas Persian miniatures were more focused on being visually interesting[4][1]. The inclusion of miniatures in Ottoman manuscripts was more for the purpose of documentation, and less about aesthetics[3]. Miniatures were used to demonstrate many important chronicles and themes, especially historical and religious events[3]. Ottoman miniatures are particularly known for their specific and accurate details[5]. This can be found in many miniatures of armies or court scenes[3].

Some Ottoman artists were more influenced by Persian miniatures than others[3]. Ottoman miniatures with strong influences from the Persian style tended towards a more romanticized account of events, which strayed away from the more typical factual accounts of other Ottoman miniature paintings[3].

Original procedure

The head painter of the miniature typically designed the composition of the scene, and his apprentices drew the contours (which were called tahrir) with black or colored ink and then painted the miniature without making an illusion of third dimension. The head painter and the scribe of the text were named and depicted in some of the manuscripts, however the apprentices were not. In the thirteenth century, author portraits were very common in Islamic manuscripts[2]. The portraits would depict the author of the manuscript as the largest figure, and would sometimes include other smaller figures that had contributed to the manuscript as well[2]. At the end of the manuscript would be a colophon, which provided details about when the manuscript was completed and the author’s name.[6]

The colors for the miniature were obtained by ground powder pigments mixed with egg-white [7] and, later, with diluted gum arabic. The produced colors were vivid. Contrasting colors used side by side with warm colors further emphasized this quality. The most used colors in Ottoman miniatures were bright red, scarlet, green, and different shades of blue.

The understanding of perspective was different from that of the nearby European

The Ottoman miniature painting tradition was unique in that artists did not strive to depict their subjects realistically[5]. Some scholars believe that this style of painting developed from shadow puppetry, on account of the sharp geometric edges, as well as the intricate architectural designs.[9] Additionally, the lack of third-dimensional shading and constant use of empty space suggest that shadow theater played a role in the development of Ottoman miniature painting.[9]

History and development

Early history

There is a relative lack of information about the book-making centers in the 15th century Ottoman Empire, but there is a local record in 1525 that indicates a studio in Istanbul[10]. It references a complex hierarchical structure, which indicates that the studio had existed for likely 50 years before this record was written[10]. This is not, however, to say that there is no evidence of production, for example: the existence of an album of calligraphy and drawings in 1481 also indicates a distinctly Ottoman studio in Istanbul[11]. But there is no distinct evidence of illustration in the Ottoman Empire prior to the conquer of Istanbul in 1453[11].

The first indication of a flourishing school of painters laid out the fundamentals of Ottoman Miniature under Mehmed II in 1451-81 but there is much more evidence of productivity in the following reign of Bayezid II (1481-1512), and there are references to specific artists under his employment[11]. The reign of Mehmed II (1451-81) is the first time that Ottoman miniature paintings are definitively created. It is worth noting that there is no archival documentation of the works, and the selection is rather limited[10]. The miniatures executed during Mehmed II's reign are also described as "crude and provincial", resulting from a relative lack of examples, perhaps indicating a lack of illustrated books in imperial libraries[11].

After the Safavid dynasty took control in 1501, the capital was moved to Tabriz, and so the center of miniature painting moved with it[1]. After the Ottoman emperor Selim I briefly conquered Tabriz in 1514, he took many manuscripts back to Istanbul, allowing for the artists there to expand on their iconographical sources[1]. This is because artists would often reference previous depictions of their subject[12].

These early studios relied on the commissions of the wealthy and powerful, including governors, and even emperors[13]. In the case of Mehmed II, Massumeh Farhad argues that Mehmed II commissioned works in attempts to achieve immortality as influenced by extensive contact with the Italians[11].

Settlement of Style

During the 1520's, the Ottoman miniature style settled, as exemplified by the Selimnâme, which was completed in 1524 and chronicled Sultan Selim 1's life, and contains contemporary costumes and events[12]. In 1527 there were 29 miniaturists in the Ottoman Court Archives[12].

Two miniaturists aided in this development,

Ottoman miniatures reached their peak in the last half of the 1500's, and compositions were largely based off of the established representations in miniature, utilizing a 'vocabulary'[12]. This style was partly characterized by a focus on everyday life[12], a relatively limited palette[1], bright colors[1], high levels of detail[1], and minimal use of the 3/4 perspective[1]. By 1557 the number of miniaturists recorded in the Ottoman court increased to 35[12].

Near the end of the 16th century (1590), Baghdad's school of painting was flourishing[14]. It had fallen into ruin after the Mongols sacked the city, but they had returned to form by this point, and there was a greater focus on everyday activities than in other locations[14]. Not only was there a move away from fantastical depictions, but also from royal contexts, and many miniatures focused instead on daily life of lower classes[14].

Later Shifts

In the 17th century, miniature painting was also popular among the citizens of Istanbul. Artists known as bazaar painters" (Turkish: çarşı ressamları) worked with other artisans in the bazaars of Istanbul at the demand of citizens.[15]

Begüm Özden Firat suggests a shift away from imperial commission after the 18th century in his book "Encounters with the Ottoman Miniature"[13]. He says this was at least partly because of miniaturists in Istanbul who did not have to answer to the same constraints as imperially commissioned miniaturists, the expansion of materials available, the establishment of murakkas (a type of album which contained a wide variety of examples of a genre) of miniatures, and the rise of new miniature painting schools[13].

Because of interactions with Europe in the 18th century, methods and subjects of miniature painting changed[13]. For example, watercolor shading rather than the traditional pigment mixed with gum arabic[13] and by the end of the 18th century, landscapes and oil portraits on canvas usurped the miniature as the dominant art form[13]. Because of contact with Italy, the basic elements of Renaissance portraiture, such as portraying the whole body, volume in the torso, and shading of the face begin to be reflected in paintings from Istanbul[11]. In the 18th century, the greater Western influence shifted the focus to one that was more subjective, to art rather than documentation[1].

Losing its function

After Levni, Westernization of Ottoman culture continued, and with the introduction of printing press and later photography, no more illuminated picture manuscripts were produced. From then on, wall paintings or oil paintings on cloth were popular. The miniature painting thus lost its function.

Contemporary Turkish miniature

After a period of crisis in the beginning of the 20th century, miniature painting was accepted as a decorative art by the intellectuals of the newly founded Turkish Republic, and in 1936, a division called Turkish Decorative Arts was established in the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul, which included miniature painting together with the other Ottoman book arts. The historian and author Süheyl Ünver educated many artists following the tradition of Ottoman book arts.

Contemporary miniature artists include Ömer Faruk Atabek, Sahin Inaloz, Cahide Keskiner, Gülbün Mesara, Nur Nevin Akyazıcı, Ahmet Yakupoğlu, Nusret Çolpan, Orhan Dağlı, and many others from the new generation. Contemporary artists usually do not consider miniature painting as merely a decorative art but as a fine art form. Different from the traditional masters of the past, they work individually and sign their works. Also, their works are not illustrating books, as was the case with the original Ottoman miniatures, but are exhibited in fine art galleries.

Gallery

-

Ottoman astronomers at work aroundIstanbul Observatory

-

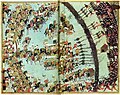

OttomanJanissaries and the defending Knights of St. John during the Siege of Rhodes(1522)

-

A Musical Gathering, Ottoman, 18th century

-

The Masjid al-Haram in Mecca depicted in the Kitāb-i Menāsik-i Hajj (1646)

-

The Dala'il al-Khayrat of Muhammad al-Jazuli (Ottoman manuscript from 1801)

-

An unhappy wife is complaining to the Kadi about her husband's impotence

-

The Sultan strews gold coins, Surname-i Hümayun (16th century)

-

Ramazan Pasha,Ottoman Algeria(16th century)

-

Ottoman official, Turkey, Istanbul, c. 1650

-

Siege of Szigetvár (1566)

-

Female musical players, from theSurname-i Vehbi(c. 1720)

-

Capture of Buda (1526)

-

Battle of Keresztes (1596)

-

War council after the unsuccessful First Siege of Vienna (1529)

-

Selim II ascends to the throne

-

Selim II ascends to the throne

-

Funeral of Murad II

-

The Ottoman army marching on the city of Tunis in 1569

-

Sultan Murad III in The Book of Felicity (1582)

-

Siege of Esztergom (1543)

See also

- Culture of the Ottoman Empire

- Persian miniature

- Mughal painting

- My Name Is Red, a historical-fiction novel involving Ottoman miniature artists

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mesinch, Maryam (December 2017). "A Comparative Analysis of Factors Influencing the Evolution of Miniature in Safavid and Ottoman Periods". International Journal of Cultural and Social Studies (3).

- ^ ISSN 0732-2992.

- ^ ISSN 0305-5167.

- ISSN 0026-3141.

- ^ ISSN 0951-0788.

- ISBN 978-0-253-00678-3.

- ^ "Turkish Miniatures". TurkishCulture.org. Turkish Cultural Foundation. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ ISSN 0277-1322.

- ^ ISSN 0732-2992.

- ^ ISSN 0571-1371.

- ^ ISSN 0571-1371.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4438-3294-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link - ^ ISBN 978-1-78076-391-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-939214-60-0.

- ^ A definition made by Metin And, in 17. Yüzyıl Türk çarşı ressamları. Tarih ve Toplum, no. 16 (April 1985): pp. 40–44

Sources

- Yapi Kredi Publications. pp. 37–42. Archived from the original(PDF) on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- Mesara, Gülbün. "TÜRK TEZHİP VE MİNYATÜR SANATI" (in Turkish). pp. 9–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

Further reading

- Fetvaci, Emine (2018). "Persian aesthetics in Ottoman albums". In Schmidtke, Sabine (ed.). Studying the Near and Middle East at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, 1935–2018. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press. pp. 402–412.

- Osmanlı Resim Sanatı (Ottoman Painted Art), Serpil Bagci, Filiz Cagman, Gunsel Renda, Zeren Tanindi

- Aşk Estetiği (The Aesthetics of Divine Love), Beşir Ayvazoğlu

- Turkish Miniature Painting, Nurhan Atasoy, Filiz Çağman

- Turkish Miniatures: From the 13th to the 18th Century, R. Ettinghausen

- Ottoman miniatures and their downfall form the theme of the 1998 novel My Name is Red by Nobel-laureate Turkish author Orhan Pamuk.

External links

- Miniature Gallery from Levni and other famous artists

- About Surname-i Vehbi

- Miniatures from the Topkapi Museum