Tyrannosauroidea

| Tyrannosauroids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Replica skeletons of Yutyrannus huali

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Coelurosauria |

| Clade: | Tyrannoraptora

|

| Superfamily: | †Tyrannosauroidea Osborn, 1906 (vide Walker, 1964) |

| Type species | |

| † Tyrannosaurus rex Osborn, 1905

| |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Tyrannosauroidea (meaning 'tyrant lizard forms') is a

Tyrannosauroids were

Description

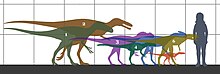

Tyrannosauroids varied widely in size, although there was a general trend towards increasing size over time. Early tyrannosauroids were small animals.

Skulls of early tyrannosauroids were long, low and lightly constructed, similar to other coelurosaurs, while later forms had taller and more massive skulls. Despite the differences in form, certain skull features are found in all known tyrannosauroids. The

Tyrannosauroids had S-shaped necks and long tails, as did most other theropods. Early genera had long forelimbs, about 60% the length of the hindlimb in Guanlong, with the typical three digits of coelurosaurs.

Characteristic features of the tyrannosauroid pelvis include a

Classification

Tyrannosaurus was named by

Scientists have commonly understood Tyrannosauroidea to include the tyrannosaurids and their immediate ancestors.

Some studies have suggested that the clade Megaraptora, usually considered to be allosauroids, are basal tyrannosauroids.[21][22] However, other authors disputed the placement of megaraptorans within Tyrannosauroidea,[23][24] and a study of megaraptoran hand anatomy published in 2016 caused even the original scientists suggesting their tyrannosauroid relationships to at least partly reject their prior conclusion.[25]

Phylogeny

While paleontologists have long recognized the family Tyrannosauridae, its ancestry has been the subject of much debate. For most of the twentieth century, tyrannosaurids were commonly accepted as members of the

In 1994, Holtz grouped tyrannosauroids with

The most basal tyrannosauroid known from complete skeletal remains is Guanlong, a representative of the family

Below on the left is a cladogram of Tyrannosauroidea from a 2022 study by Darren Naish and Andrea Cau on the genus Eotyrannus, and on the right is a cladogram of Eutyrannosauria from a 2020 study by Jared T. Voris and colleagues on the genus Thanatotheristes:[42][43]

|

|

Phylogeography

In 2018 authors Rafael Delcourt and Orlando Nelson Grillo published a phylogenetic analysis of Tyrannosauroidea which incorporated taxa from the ancient continent of Gondwana (which today consists of the southern hemisphere), such as Santanaraptor and Timimus, whose placement in the group has been controversial.[44] They have found that not only Santanaraptor and Timimus were placed as tyrannosaurs more derived than Dilong, but they have found in their analysis that tyrannosauroids were widespread in Laurasia and Gondwana since the Middle Jurassic.[44] They have proposed new subclade names for Tyrannosaurioidea. The first is Pantyrannosauria referring to all non-proceratosaurid members of the group, while Eutyrannosauria for larger tyrannosaur taxa found in the northern hemisphere such as Dryptosaurus, Appalachiosaurus, Bistahieversor, and Tyrannosauridae.[44] Below is their phylogeographic tree they have recovered, in which displays the phylogenetic relationships of the taxa as well as the continents those taxa have been found.[44]

| Tyrannosauroidea |

| ||||||

In 2021, Chase Brownstein published a research article based on more thorough descriptions of tyrannosauroid

Distribution

The tyrannosauroids lived on the supercontinent Laurasia, which split from Gondwana in the Middle Jurassic. The earliest recognized tyrannosauroids lived in the Middle Jurassic, represented by the proceratosaurids Kileskus from the Western Siberia and Proceratosaurus from Great Britain. Upper Jurassic tyrannosauroids include Guanlong from China, Stokesosaurus from the western United States and Aviatyrannis and Juratyrant from Europe.

Early Cretaceous tyrannosauroids are known from Laurasia, being represented by Eotyrannus from England[5] and Dilong, Sinotyrannus, and Yutyrannus from northeastern China. Early Cretaceous tyrannosauroid premaxillary teeth are known from the Cedar Mountain Formation in Utah[46] and the Tetori Group of Japan.[47]

The Middle Cretaceous record of Tyrannosauroidea is rather patchy. Teeth and indeterminate postcrania of this interval are known from the Cenomanian-age

Paleobiology

Facial tissue

A conference paper by Tracy Ford states that there was rough bone texture on the skulls of theropods and higher foramina frequency than lepidosaurs and mammals which would be evidential for a sensitive snout for theropods.[56][57] A study in 2017 study about a new tyrannosaurid named Daspletosaurus horneri was published in the journal Scientific Reports. Paleontologist Thomas Carr analyzed the craniofacial texture of Daspletosaurus horneri and observed a hummocky rugosity which compared to crocodilian skulls and suggesting Daspletosaurus horneri including all tyrannosaurids have flat sensory scales. The subordinate regions were analyzed to have cornified epidermis.[58] However, a 2018 presentation has an alternative interpretation. Crocodilians don't have flat sensory scales but rather cracked cornified epidermis due to growth. The hummocky rugosity in the skulls of lepidosaurs have correlation with scales which this bone texture is also present in tyrannosaurid skulls. The foramina frequency in theropod skulls does not exceed 50 foramina which shows that theropods had lips. It's been proposed that lips are a primitive trait in tetrapods and the soft tissue present in crocodilians are a derived trait because of aquatic or semiaquatic adaptations.[59][60][61][62][63]

Body integument

Long

The presence of feathers in basal tyrannosauroids is not surprising since they are now known to be characteristic of coelurosaurs, found in other basal genera like

Head crests

Bony crests are found on the skulls of many theropods, including numerous tyrannosauroids. The most elaborate is found in Guanlong, where the nasal bones support a single, large crest which runs along the midline of the skull from front to back. This crest was penetrated by several large foramina (openings) which reduced its weight.[3] A less prominent crest is found in Dilong, where low, parallel ridges run along each side of the skull, supported by the nasal and lacrimal bones. These ridges curve inwards and meet just behind the nostrils, making the crest Y-shaped.[2] The fused nasals of tyrannosaurids are often very rough-textured. Alioramus, a possible tyrannosaurid from Mongolia, bears a single row of five prominent bony bumps on the nasal bones; a similar row of much lower bumps is present on the skull of Appalachiosaurus, as well as some specimens of Daspletosaurus, Albertosaurus, and Tarbosaurus.[8] In Albertosaurus, Gorgosaurus and Daspletosaurus, there is a prominent horn in front of each eye on the lacrimal bone. The lacrimal horn is absent in Tarbosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, which instead have a crescent-shaped crest behind each eye on the postorbital bone.[1]

These head crests may have been used for

Reproduction

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2020) |

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ S2CID 4381777.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ S2CID 4424849.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Tyrannosaurus ancestor's teeth found in Hyogo". The Japan Times. 2009-06-21. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ^ S2CID 16881410.

- ^ S2CID 45978858.

- ^ Handwerk, B. (16 September 2010). "Tyrannosaurs were human-size for 80 million years". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ S2CID 86243316.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Quinlan, Elizibeth D.; Derstler, Kraig; & Miller, Mercedes M. (2007). "Anatomy and function of digit III of the Tyrannosaurus rex manus". Geological Society of America Annual Meeting — Abstracts with Programs: 77. Archived from the original on 2008-02-24. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) [abstract only] - ^ .

- JSTOR 3889334. Archived from the originalon 2007-12-12.

- S2CID 4389633.

- doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011003. Archived from the originalon 2010-07-15.

- ^ S2CID 129684676.

- hdl:2246/1464.

- ^ S2CID 86378219.

- ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5.

- ^ OCLC 21966322.[page needed]

- .

- ^ Sereno, Paul C. (2005). "Stem Archosauria — TaxonSearch, Version 1.0". Archived from the original on 2007-12-26. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ^ F. E. Novas; F. L. Agnolín; M. D. Ezcurra; J. I. Canale; J. D. Porfiri (2012). "Megaraptorans as members of an unexpected evolutionary radiation of tyrant-reptiles in Gondwana". Ameghiniana. 49 (Suppl): R33.

- hdl:11336/12129.

- .

- ^ .

- hdl:11336/48895.

- ISBN 978-0-89464-985-1.[page needed]

- ISBN 978-0-940228-14-6.

- ISBN 978-0-520-06727-1.

- ISBN 978-84-86788-14-8.

- hdl:2246/1300.

- .

- ^ S2CID 83726237.

- PMID 10381873.

- ^ )

- Currie, Philip J.; Hurum, Jørn H; & Sabath, Karol. (2003). "Skull structure and evolution in tyrannosaurid phylogeny" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 48 (2): 227–234.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ hdl:2246/5823.

- PMID 10381873.

- .

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. (2005-09-20). "RE: Burpee Conference (LONG)". Archives of the Dinosaur Mailing List. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- S2CID 7350556.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- PMID 35821895.

- S2CID 213838772.

- ^ S2CID 133830150.

- ^ PMID 34457333.

- ^ Kirkland, James I.; Carpenter, Kenneth(1997). "Lower to Middle Cretaceous Dinosaur faunas of the central Colorado Plateau: a key to understanding 35 million years of tectonics, sedimentology, evolution, and biogeography". Brigham Young University Geology Studies. 42 (II): 69–103.

- S2CID 130306877.

- S2CID 90633156.

- ^ Nesov, Lev A. (1995). Dinosaurs of Northern Eurasia: new data about assemblages, ecology and paleobiogeography (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Scientific Research Institute of the Earth's Crust, St. Petersburg State University. p. 156pp.

- S2CID 86614424.

- S2CID 146115938.

- S2CID 130766946.

- S2CID 206525597. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- S2CID 6772287.

- PMID 34457333.

- ^ Ford, Tracy (January 2015). "Tactile Faced Theropods". ResearchGate.

- ^ Ford, Tracy (1997-11-15). "Ford, T. L., 1997, Did Theropods have Lizard Lips?: Southwest Paleontological Symposium – Proceedings, 1997, p. 65-78". Mesa Southwest Museum and Southwest Paleontological Society. 1: 65–78.

- PMID 28358353.

- ^ Witton, Mark; Hone, David (2018). "Tyrannosaurid theropods: did they ever smile like crocodiles? p. 67" (PDF). The Annual Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Reisz, Robert; Larson, Derek (2016). "Dental anatomy and skull length to tooth size ratios support the hypothesis that theropod dinosaurs had lips" (PDF). 4th Annual Meeting, 2016, Canadian Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology.

- ^ Morhardt, Ashely (2009). "Dinosaur smiles: Do the texture and morphology of the premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary bones of sauropsids provide osteological correlates for inferring extra-oral structures reliably in dinosaurs?" (PDF). Retrieved July 15, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- S2CID 6859452.

- S2CID 13465548.

- ^ S2CID 4412725.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ S2CID 4430927.

- S2CID 4426803.

- PMID 17521978.

- S2CID 29689629. Archived from the original(PDF) on 17 April 2012.

- S2CID 85701665.

- PMID 28592520.

- PMID 19422430.

- S2CID 206544531.

- S2CID 105753275.

- hdl:10088/8045.

External links

![]() Media related to Tyrannosauroidea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tyrannosauroidea at Wikimedia Commons

- List of tyrannosauroid specimens and species at The Theropod Database.