Iraq–United States relations

| |

Iraq |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

Iraqi Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Baghdad |

In January 2020, Iraq voted to ask the U.S. and its coalition members to withdraw all of their troops from the country after the assassinations of Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani (the second most powerful figure in Iran[3]) and PMF commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis (one of Iraq's most powerful men[4]).[5] Following the vote, U.S. President Donald Trump initially refused to withdraw from Iraq, but began withdrawing forces in March 2020.[6] On 26 July 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden announced that the American combat mission in Iraq would conclude by the end of 2021 and the remaining U.S. troops in the country would shift to an advisory role.[7]

Ottoman Empire

American commercial interaction with the Ottoman Empire (which included the area that later became modern Iraq) began in the late 18th century. In 1831, Chargé d'Affaires David Porter became the first American diplomat in the Ottoman Empire, at the capital city of Constantinople. With the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, the United States supported Great Britain's administration of Iraq as a mandate, but insisted that it be groomed for independence, rather than remain a colony.[8] U.S. first became involved in Iraq in the 1920s as part of an effort to secure a role for American companies in Iraq's emerging oil industry. As part of the 1928 Red Line Agreement, UK, US, France and the Netherlands effectively agreed to share out Iraq's oil, with American oil companies gaining a 23.75 percent ownership share of the Iraq Petroleum Company.[9][10][11]

U.S. recognizes Iraq

The U.S. recognized Iraq on January 9, 1930, when

Arab Union

On May 28, 1958, the U.S. recognized the

Relations with Qasim's government, 1958–1963

Relations between the U.S. and Iraq became strained following

On June 25, 1961, Qasim mobilized troops along the

Following Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani's 1958 return to Iraq from exile in the Soviet Union, Qasim had promised to permit autonomous rule in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq, but by 1961 Qasim had made no progress towards achieving this goal. In July 1961, following months of violence between feuding Kurdish tribes, Barzani returned to northern Iraq and began retaking territory from his Kurdish rivals. Although Qasim's government did not respond to the escalating violence, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) sent Qasim a list of demands in August, which included the withdrawal of Iraqi government troops from Kurdish territory and greater political freedom.[19] For the next month, U.S. officials in Iran and Iraq predicted that a war was imminent. Faced with the loss of northern Iraq after non-Barzani Kurds seized control of a key road leading to the Iran–Iraq border in early September and ambushed and massacred Iraqi troops on September 10 and September 12, Qasim finally ordered the systematic bombing of Kurdish villages on September 14, which caused Barzani to join the rebellion on September 19.[20] As part of a strategy devised by Alexander Shelepin in July 1961 to distract the U.S. and its allies from the Soviet Union's aggressive posture in Berlin, the Soviet KGB revived its connections with Barzani and encouraged him to revolt, although Barzani had no intention to act as their proxy. By March 1962, Barzani's forces were in firm control of Iraqi Kurdistan, although Barzani refrained from taking major cities out of fear that the Iraqi government would launch reprisals against civilians. The U.S. refused Kurdish requests for assistance, but Qasim nevertheless castigated the Kurds as "American stooges" while absolving the Soviets of any responsibility for the unrest.[21][22][23]

In December 1961, Qasim's government passed Public Law 80, which restricted the British- and American-owned Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC)'s concessionary holding to those areas in which oil was actually being produced, effectively expropriating 99.5% of the IPC concession. U.S. officials were alarmed by the expropriation as well as the recent Soviet veto of an Egyptian-sponsored UN resolution requesting the admittance of Kuwait as a UN member state, which they believed to be connected. Senior National Security Council (NSC) adviser Robert Komer worried that if the IPC ceased production in response, Qasim might "grab Kuwait" (thus achieving a "stranglehold" on Middle Eastern oil production) or "throw himself into Russian arms." At the same time, Komer made note of widespread rumors that a nationalist coup against Qasim could be imminent, and had the potential to "get Iraq back on [a] more neutral keel."[24] Following Komer's advice, on December 30 Kennedy's National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy sent the President a cable from the U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, John Jernegan, which argued that the U.S. was "in grave danger [of] being drawn into [a] costly and politically disastrous situation over Kuwait." Bundy also requested Kennedy's permission to "press State" to consider measures to resolve the situation with Iraq, adding that cooperation with the British was desirable "if possible, but our own interests, oil and other, are very directly involved."[25][26]

In April 1962, the State Department issued new guidelines on Iraq that were intended to increase American influence in the country. Around the same time, Kennedy instructed the

After reaching a secret agreement with Barzani to work together against Qasim in January, the anti-imperialist and anti-communist Iraqi Ba'ath Party overthrew and executed Qasim in a violent coup on February 8, 1963. It has long been suspected that the Ba'ath Party collaborated with the CIA in planning and carrying out the coup.[34][35] Pertinent contemporary documents relating to the CIA's operations in Iraq have remained classified,[36][37] and modern academia have "remain[ed] divided in their interpretations of American foreign policy toward the February 1963 coup in Iraq."[38][39] Bryan R. Gibson and Peter Hahn (in separate works) argue that although the U.S. had been notified of two aborted Ba'athist coup plots in July and December 1962, publicly declassified documents do not support claims of direct American involvement in the 1963 coup.[40][41][42] On the other hand, Brandon Wolfe-Hunnicutt cites "compelling evidence of an American role,"[38] and that publicly declassified documents "largely substantiate the plausibility" of CIA involvement in the coup.[43] Eric Jacobsen, citing the testimony of contemporary prominent Ba'athists and U.S. government officials, states that ample evidence exists of the CIA having assisted the Ba'athists in planning the coup.[44]

Qasim's former deputy

The Ba'athist government collapsed in November 1963 over the question of unification with Syria (where a different branch of the Ba'ath Party had seized power in March) and the extremist and uncontrollable behavior of al-Sa'di's National Guard. President Arif, with the overwhelming support of the Iraqi military, purged Ba'athists from the government and ordered the National Guard to stand down; although al-Bakr had conspired with Arif to remove al-Sa'di, on January 5, 1964, Arif removed al-Bakr from his new position as Vice President, fearful of allowing the Ba'ath Party to retain a foothold inside his government.[56] On November 21, 1963, the Kennedy administration determined that because Arif remained the Iraqi head of state, diplomatic relations with Iraq would continue unimpeded.[57]

Lyndon Johnson administration

Under the Presidencies of Arif, and, especially, his brother

Before leaving Baghdad on June 10, 1967, U.S. ambassador Enoch S. Duncan handed over the keys to the U.S. embassy to Belgian ambassador Marcel Dupret. Belgium became the

On August 2, Iraqi Foreign Minister Abdul Karim Sheikhli announced that Iraq would seek close ties "with the socialist camp, particularly the Soviet Union and the Chinese People's Republic." By late November, the U.S. embassy in Beirut reported that Iraq had released many leftist and communist dissidents, although "there [was] no indication ... [they had] been given any major role in the regime." As the Arif government had recently signed a major oil deal with the Soviets, the Ba'ath Party's rapid attempts to improve relations with Moscow were not a complete shock to U.S. policymakers, but they "provided a glimpse at a strategic alliance that would soon emerge."[75] In December, Iraqi troops based in Jordan "made international headlines" when they began shelling Israeli settlers in the Jordan Valley, which led to a strong response by the Israeli Air Force.[76] al-Bakr claimed that a "fifth column of agents of Israel and the U.S. was striking from behind," and, on December 14, the Iraqi government alleged it had discovered "an Israeli spy network" plotting to "bring about a change in the Iraqi regime," arresting dozens of individuals and eventually executing 9 Iraqi Jews in January 1969. U.S. officials found the charges improbable, as Iraqi Jews were "under constant surveillance [and therefore] would make poor recruits for any Israeli espionage or sabotage net."[77][78] Contributing to the growing atmosphere of crisis, the Ba'ath Party also escalated the conflict with Barzani by providing aid to Jalal Talabani's rival Kurdish faction.[79] From the beginning, Johnson administration officials were concerned about "how radical" the Ba'athist government would be—with John W. Foster of the NSC predicting immediately after the coup that "the new group ... will be more difficult than their predecessors"—and, although initial U.S. fears that the coup had been supported by the "extremist" sect of the Ba'ath Party that seized control of Syria in 1966 quickly proved unfounded, by the time President Johnson left office there was a growing belief "that the Ba'ath Party was becoming a vehicle for Soviet encroachment on Iraq's sovereignty."[80][81][82]

Alleged U.S. support for 1970 anti-Ba'athist coup attempt

The

The Shah's aggressive actions convinced Iraq to seek an end to the Kurdish War. In late December 1969, al-Bakr sent his deputy, Saddam Hussein, to negotiate directly with Barzani and his close aide Dr. Mahmoud Othman. The Shah was outraged when he learned of these negotiations, and sponsored a coup against the Iraqi government, which was scheduled for the night of January 20–21, 1970. However, Iraq's security forces had "complete recordings of most of the meetings and interviews that took place," foiling the plot, expelling the Iranian ambassador to Iraq, and executing "at least 33 conspirators" by January 23.[90] On January 24, Iraq announced its support for Kurdish autonomy, and on March 11, Saddam and Barzani reached an agreement (dubbed the "March Accord") "to recognize the binational character of Iraq ... [and] allow for the establishment of a self-governing region of Kurdistan," which was to be implemented by March 1974, although U.S. officials were skeptical that the agreement would prove binding.[91]

There were allegations of American involvement in the failed 1970 coup attempt, which involved a coalition of Iraqi factions, including Kurdish opponents of the Ba'ath Party. Edmund Ghareeb claimed that the CIA reached an agreement to help the Kurds overthrow the Iraqi government in August 1969, although there is little evidence to support this claim, and the CIA officer in charge of operations in Iraq and Syria in 1969 "denied any U.S. involvement with the Kurds prior to 1972." The State Department was informed of the plot by Iraqi businessman Loufti Obeidi on August 15, but strongly refused to provide any assistance.[92] Iraqi exile Sa'ad Jabr discussed the coup planning with officials at the U.S. embassy in Beirut on December 8; embassy officials reiterated that the U.S. could not involve itself in the conspiracy, although on December 10 the State Department authorized the embassy to tell Jabr "we would be prepared to consider prompt resumption of diplomatic relations and would certainly be disposed to cooperate within the limits of existing legislation and our overall policy" if the "new government prove[d] to be moderate and friendly."[93][94][95]

Kurdish intervention, 1972–1975

In the aftermath of the March Accord, Iranian and Israeli officials tried to persuade the Nixon administration that the agreement was part of a Soviet plot to free up Iraq's military for aggression against Iran and Israel, but U.S. officials refuted these claims by noting that Iraq had resumed purging ICP members on March 23, 1970, and that Saddam was met with a "chilly" reception during his visit to Moscow on August 4–12, during which he requested deferment on Iraq's considerable foreign debt.[96] Iraqi–Soviet relations improved rapidly in late 1971 in response to the Soviet Union's deteriorating alliance with Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat, who succeeded Gamal Abdel Nasser following Nasser's death on September 28, 1970.[97] However, even after Iraq signed a secret arms deal with the Soviets in September 1971, which was finalized during Soviet Defense Minister Andrei Grechko's December trip to Baghdad and "brought the total of Soviet military aid to Iraq to above the $750 million level," the State Department remained skeptical that Iraq posed any threat to Iran.[98][99] On April 9, 1972, Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin signed "a 15-year treaty of friendship and cooperation" with al-Bakr, but U.S. officials were not "outwardly perturbed" by this development, because, according to the NSC staff, it was not "surprising or sudden but rather a culmination of existing relationships."[100][101]

It has been suggested that Nixon was initially preoccupied with pursuing his policy of

From October 1972 until the abrupt end of the Kurdish intervention after March 1975, the CIA "provided the Kurds with nearly $20 million in assistance," including 1,250 tons of non-attributable weaponry.

On March 11, 1974, the Iraqi government gave Barzani 15 days to accept a new autonomy law, which "fell far short of what the regime had promised the Kurds in 1970, including long-standing demands like a proportional share of oil revenue and the inclusion of the oil-rich and culturally significant city of Kirkuk into the autonomous region" and "gave the regime a veto over any Kurdish legislation."

A

Iran-Iraq War and resumption of diplomatic ties

Even though Iraqi interest in American technical expertise was strong, prior to 1980 the government did not seem to be seriously interested in re-establishing diplomatic relations with the United States. The Ba'ath Party viewed the efforts by the United States to achieve "step-by-step" interim agreements between

A review of thousands of declassified government documents and interviews with former U.S. policymakers shows that the U.S. provided intelligence and logistical support, which played a role in arming Iraq during the Iran–Iraq War. Under the Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations, the U.S. authorized the sale to Iraq of numerous dual-use technology (items with both military and civilian applications), including chemicals which can be used in manufacturing of pesticides or chemical weapons and live viruses and bacteria, such as anthrax and bubonic plague used in medicine and the manufacture of vaccines or weaponized for use in biological weapons.

A report of the U.S. Senate's Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs concluded that the U.S. under the successive presidential administrations sold materials including anthrax, and botulism to Iraq right up until March 1992. The chairman of the Senate committee, Don Riegle, said: "The executive branch of our government approved 771 different export licenses for sale of dual-use technology to Iraq. I think it's a devastating record."[135] According to several former officials, the State and Commerce departments promoted trade in such items as a way to boost U.S. exports and acquire political leverage over Saddam.[136]

Relations between the U.S. and Iraq were strained by the Iran–Contra affair.

The U.S. provided critical battle planning assistance at a time when U.S. intelligence agencies knew that Iraqi commanders would employ chemical weapons in waging the war, according to senior military officers with direct knowledge of the program. The U.S. carried out this covert program at a time when Secretary of State

Concern about the 1979

In early 1988, Iraq's relations with the United States were generally cordial. The relationship had been strained at the end of 1986 when it was revealed that the United States had secretly sold arms to Iran during 1985 and 1986, and a crisis occurred in May 1987 when an Iraqi pilot bombed an American naval ship in the Persian Gulf, a ship he mistakenly thought to be involved in Iran-related commerce. Nevertheless, the two countries had weathered these problems by mid-1987. Although lingering suspicions about the United States remained, Iraq welcomed greater, even if indirect, American diplomatic and military pressure in trying to end the war with Iran. For the most part, the Iraqi government believed the United States supported its position that the war was being prolonged only because of Iranian intransigence.

Gulf War

On July 25, 1990, following tensions with Kuwait, Saddam met with United States Ambassador to Baghdad, April Glaspie, in one of the last high-level contacts between the two Governments before the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990. Iraqi Government officials published a transcript of the meeting, which also included the Iraqi Foreign Minister, Tariq Aziz. A copy was provided to The New York Times by ABC News, which was translated from Arabic. The U.S. State Department has declined to comment on its accuracy.

Glaspie is quoted saying to Saddam:

I have a direct instruction from the President to seek better relations with Iraq ... I know you need funds. We understand that and our opinion is that you should have the opportunity to rebuild your country. But we have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait. I was in the American Embassy in Kuwait during the late 60s [during another Iraq-Kuwait border conflict]. The instruction we had during this period was that we should express no opinion on this issue and that the issue is not associated with America. James Baker has directed our official spokesmen to emphasize this instruction. We hope you can solve this problem using any suitable methods via Klibi or via

President Mubarak. All that we hope is that these issues are solved quickly ... Frankly, we can see only that you have deployed massive troops in the south. Normally that would not be any of our business. But when this happens in the context of what you said on your national day, then when we read the details in the two letters of the Foreign Minister, then when we see the Iraqi point of view that the measures taken by the U.A.E. and Kuwait is, in the final analysis, parallel to military aggression against Iraq, then it would be reasonable for me to be concerned. And for this reason, I received an instruction to ask you, in the spirit of friendship—not in the spirit of confrontation—regarding your intentions.[141]

However, Tariq Aziz told

There were no mixed signals. We should not forget that the whole period before August 2 witnessed a negative American policy towards Iraq. So it would be quite foolish to think that, if we go to Kuwait, then America would like that. Because the American tendency ... was to untie Iraq. So how could we imagine that such a step was going to be appreciated by the Americans? It looks foolish, you see, this is fiction. About the meeting with April Glaspie—it was a routine meeting. There was nothing extraordinary in it. She didn't say anything extraordinary beyond what any professional diplomat would say without previous instructions from his government. She did not ask for an audience with the president. She was summoned by the president. He telephoned me and said, "Bring the American ambassador. I want to see her." She was not prepared, because it was not morning in Washington. People in Washington were asleep, so she needed a half-hour to contact anybody in Washington and seek instructions. So, what she said were routine, classical comments on what the president was asking her to convey to President Bush. He wanted her to carry a message to George Bush—not to receive a message through her from Washington.[143]

Due to ongoing concerns over the security situation in Iraq, the U.S. State Department invalidated U.S. passports for travel to or through Iraq on February 8, 1991. The Gulf War cease-fire was negotiated at Safwan, Iraq on March 1, 1991, taking effect on April 11, 1991.[144]

According to former U.S. intelligence officials interviewed by

As a result of the war, Iraq and the United States broke off diplomatic relations for a second time. From 1990 to 2003, Algeria served as Iraq's protecting power in Washington, while Poland served as the protecting power for the United States in Baghdad.[148] Diplomatic relations would not be restored until the United States overthrew Saddam Hussein in 2003 and established an American-aligned government.

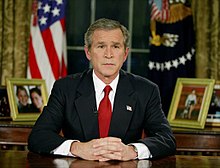

2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq

After the

In late 2001,

In the lead-up to the invasion, the U.S. and U.K. emphasized the argument that

Accusations of faulty evidence and alleged shifting rationales became the focal point for critics of the war, who charge that the Bush Administration purposely fabricated evidence to justify an invasion that it had long planned to launch.[153]

Shortly after the invasion, the

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan described the war as illegal, saying in a September 2004 interview that it was "not in conformity with the Security Council."[156]

The U.S. began withdrawing its troops in the winter of 2007–08. The winding down of U.S. involvement in Iraq accelerated under President Barack Obama. The U.S. formally withdrew all combat troops from Iraq by December 2011.[157]

Current status

The United States helped establish the Central Bank of Iraq in 2004, and since then the U.S. dollar has become the country's chief currency because of Iraq's large informal economy which runs on cash.[158]

The

In January 2017, US President Donald Trump issued an executive order banning the entry of all Iraqi citizens, as well as citizens of six other countries. After sharp criticism and public protests as well as lawsuits against the executive order, Trump relaxed the travel restrictions and dropped Iraq from the list of non-entry countries in March 2017.[160][161][162]

As of October 2019, United States continued to use Iraqi bases for conducting operations such as the

On 31 December 2019, the U.S. embassy in Baghdad was attacked by supporters of Popular Mobilization Forces militia in response to U.S. airstrikes on 29 December 2019.[163]

After a

As per two Iraqi government sources, the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Iraq's President Barham Salih held a telephonic conversation in the mid of September 2020. In the call Pompeo discussed about bringing back US diplomats from Iraq followed by a threat to shut down the US Embassy in Iraq. Iraqi authorities feared the withdrawal of diplomat(s) would lead to military confrontation with Iran, whom the United States blamed for missile and bomb attacks.[168]

See also

- 1991 Iraqi uprisings

- 1998 bombing of Iraq

- 2017 Mosul airstrike

- Casualties of the Iraq War

- CIA activities in Iraq

- Criticism of the Iraq War

- Cruise missile strikes on Iraq (June 1993)

- Embassy of the United States in Baghdad

- Gulf War

- Human rights in Saddam Hussein's Iraq

- Iraqi Americans

- Iran–Iraq relations

- Iraq–Israel relations

- Iraq–Russia relations

- Iran–United States relations

- Legality of the Iraq War

- Opposition to the Iraq War

- Rationale for the Iraq War

- Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda link allegations

- Sanctions against Iraq

- Timeline of the Iraq War

- United States Ambassador to Iraq

- United States support for Iraq during the Iran–Iraq War

- US-led intervention in Iraq (2014–2021)

- Occupation of Iraq (2003–2011)

References

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (Winter 2016). "Sold Out? US Foreign Policy, Iraq, the Kurds, and the Cold War by Bryan R. Gibson (review)". The Middle East Journal. 70 (1). Middle East Institute.

While the United States has been deeply involved in Iraq since the 1980s, the historiography of US-Iraqi relations remains woefully underdeveloped. Until very recently, historians interested in the origins of the US-Iraqi relationship have had very few scholarly resources to consult. In recent years, articles on various aspects of US policy toward Iraq during the 1950s and early 1960s have begun to appear in scholarly journals, but Bryan Gibson's Sold Out? represents the first monograph based on recently declassified American archival sources.

- ^ a b "Trump' Syria Troop Withdrawal Complicated Plans for al-Baghdadi Raid - The New York Times". The New York Times. 27 October 2019. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ Nakhoul, Samia (3 January 2020). "U.S. killing of Iran's second most powerful man risks regional conflagration". Reuters.

- ^ Bulos, Nabih (6 January 2020). "The U.S. airstrike that killed a top Iranian general also eliminated another key player". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "WSVN: Iraq Parliament votes to expel US Military". 5 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-01-05. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ "US cites 'great sacrifice' as it pulls 2,200 troops out of Iraq". Al Jazeera. 9 September 2020.

- ^ Szuba, Jared (July 26, 2021). "Biden announces end to US combat mission in Iraq". Al-Monitor.

- ^ a b c "A Guide to the United States' History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Iraq". Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs: United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 2018-12-05. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- ^ "FACTBOX-A history of foreign oil firms in Iraq". Reuters. December 7, 2009.

- )

- ^ "What is the history of oil in Iraq?". Britannica ProCon. 6 April 2008.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 19–20.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-1960, Near East Region; Iraq; Iran; Arabian Peninsula, Volume XII. 1958-07-14. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 27–28, 35.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 36.

- ^ "Gauging the Iraqi Threat to Kuwait in the 1960s — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-03-24. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 37.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 38–40, 200.

- ISBN 9780195333381.

By 1962, the U.S. relationship with Qassim was stabilized. ... Resolution of a potential conflict over the IPC signified determination in both Washington and Baghdad to stabilize relations. ... Barzani envoys called on U.S. officials in Baghdad and Washington, requesting arms supply and political support and offering to help defeat communism in Iraq, return Iraq to the Baghdad Pact, and provide intelligence about neighboring states. State Department officials refused these requests on the grounds that the Kurdish problem was an internal matter for Iraq, Iran, and Turkey to handle. 'It has been firm U.S. policy to avoid involvement in any way with opposition to Qas[s]im,' State Department officials noted in 1962, 'even with Iraqis who profess basic friendliness to the U.S.' ... King Hussein of Jordan later alleged that U.S. intelligence supplied the Baath with the names and addresses of those Communists, and an Iraqi Baathist leader confirmed to the scholar Hanna Batatu that the Baath had maintained contacts with American officials during the Qassim era. (Declassified U.S. government documents offer no evidence to support these suggestions.)

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XVIII, Near East, 1962–1963. 1962-09-20. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-11-21. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 37, 40–42.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 35, 41–43.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XVII, Near East, 1961–1962. 1961-12-29. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 47–48.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XVII, Near East, 1961–1962. 1962-06-02. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 48, 51–54, 219.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XVIII, Near East, 1962–1963. 1963-02-05. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 45, 217.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 200.

- ISSN 0145-2096.

While scholars and journalists have long suspected that the CIA was involved in the 1963 coup, as yet, there is very little archival analysis of the question. The most comprehensive study put forward thus far finds "mounting evidence of U.S. involvement" but ultimately runs up against the problem of available documentation.

- ISBN 9780857713087.

Washington wanted to see Qasim and his Communist supporters removed, but that is a far cry from Batatu's inference that the U.S. had somehow engineered the coup. The U.S. lacked the operational capability to organize and carry out the coup, but certainly after it had occurred the U.S. government preferred the Nasserists and Ba'athists in power, and provided encouragement and probably some peripheral assistance.

- ISSN 0145-2096.

The CIA records required to set forward definitive claims regarding U.S. covert operations in Iraq remain classified.

- ISSN 1471-6380.

Archival sources on the U.S. relationship with this regime are highly restricted. Many records of the Central Intelligence Agency's operations and the Department of Defense from this period remain classified, and some declassified records have not been transferred to the National Archives or cataloged.

- ^ S2CID 157328042.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. xvii.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 45, 57–58.

- ISBN 9780195333381.

Declassified U.S. government documents offer no evidence to support these suggestions.

- ISBN 0-88349-116-8.

- ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

- ISSN 0145-2096.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 59–60, 77.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 60–61.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XVIII, Near East, 1962–1963. 1963-02-08. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 66.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 69–71, 76, 80.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 80.

- ISBN 9781108107556.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 71–75.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (March 2011). "The End of the Concessionary Regime: Oil and American Power in Iraq, 1958-1972" (PDF). pp. 117–119. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 77, 85.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 79.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 83–84, 95, 102.

- ISBN 9780195333381.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 94–98.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 98–99.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXI, Near East Region; Arabian Peninsula. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-05. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 99, 102.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 99.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXI, Near East Region; Arabian Peninsula. 1967-01-21. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-05. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 36, 100.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 101–105, 111.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 94, 105, 110–111.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (March 2011). "The End of the Concessionary Regime: Oil and American Power in Iraq, 1958-1972". pp. 146–150, 154, 193–194. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ a b Gibson 2015, p. 105.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 111.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 104, 112.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (March 2011). "The End of the Concessionary Regime: Oil and American Power in Iraq, 1958-1972". pp. 225–226, 229–231. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 111, 113.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 113.

- ^ a b Gibson 2015, pp. 114, 119.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1969-02-14. Archivedfrom the original on April 5, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 114.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 99, 113, 116.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXI, Near East Region; Arabian Peninsula. 1968-07-17. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXI, Near East Region; Arabian Peninsula. 1968-07-22. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ISBN 9780520921245.—increasing the area of sensual contact between mutilated body and mass—vary from 150,000 to 500,000. Peasants streamed in from the surrounding countryside to hear the speeches. The proceedings, along with the bodies, continued for twenty-four hours, during which the President, Ahmad Hasan al-Bakr, and a host of other luminaries gave speeches and orchestrated the carnival-like atmosphere.

Estimates on the size of the crowds that came to view the dangling corpses spread seventy meters apart in Liberation Square

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 119.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 107–111, 119.

- ISBN 9780415685245.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 185.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 110, 122–123.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 123–124, 151.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1969-08-15. Archivedfrom the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 121–122.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1969-12-08. Archivedfrom the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1969-12-10. Archivedfrom the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 124–127.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 130–131.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1972-01-22. Archivedfrom the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 134–135.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1972-05-18. Archivedfrom the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1972-05-31. Archivedfrom the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 117, 128, 135–142, 163.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 140, 144–145, 148, 181.

- ^ a b Gibson 2015, p. 205.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 146–148.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1972-07-28. Archivedfrom the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 163.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 144.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. 1972-10-21. Archivedfrom the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 144–146, 148–150, 152–153, 157–158.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XXVII, Iran; Iraq, 1973–1976. 1973-09-05. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-29. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 161.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 167.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 166–171.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 169–171, 175, 177, 180, 204.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 181, 186, 190–191, 194–195, 204.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 59, 178, 183–185, 188, 190–191, 204.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XXVII, Iran; Iraq, 1973–1976. 1975-03-08. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 195, 205.

- ^ Safire, William (1976-02-04). "Mr. Ford's Secret Sellout". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 163, 171, 192, 204, 240.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 166–171, 204.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XXVII, Iran; Iraq, 1973–1976. 1974-04-17. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 167, 171, 204.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 187–192.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 169, 194, 204–205.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XXVII, Iran; Iraq, 1973–1976. 1974-03-26. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ Gibson 2015, p. 196.

- ^ Gibson has in turn been criticized for overstating his disagreement with the Pike Report and for neglecting Barzani's own claim that the latter's rejection of the Ba'ath Party's autonomy law was largely predicated on the promise of U.S. support. See Vis, Andrea (October 2015). "U.S. Foreign Policy on the Kurds of Iraq: 1958–1975". pp. 49–51. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Hiltermann, Joost (2016-11-17). "They were expendable". London Review of Books. 38 (22). Archived from the original on 2017-02-16. Retrieved 2017-02-15.

- ^ Sunday Herald (Scotland) September 8, 2002.

- ^ Washington Post, December 30, 2002.

- ^ New York Times, August 18, 2002.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55587-250-2.

- ^ Douglas A. Borer (2003). "Inverse Engagement: Lessons from U.S.-Iraq Relations, 1982–1990". U.S. Army Professional Writing Collection. U.S. Army. Archived from the original on 11 October 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ^ Gamarekian, Barbara (6 February 1985). "Diplomatics Inch, Diplomatic Mile". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Excerpts From Iraqi Document on Meeting With U.S. Envoy Archived 2017-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times. September 23, 1990.

- ^ "The Gulf War", PBS Frontline. January 9, 1996.

- ^ "The survival of Saddam" Archived 2017-08-08 at the Wayback Machine, PBS Frontline. January 25, 2000.

- ^ Torreon, B.S. (2011). U.S. Periods of War and Dates of Current Conflicts. CRS Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS21405.pdf Archived 2015-03-28 at the Wayback Machine

- New York Times.

- ^ Association of Former Intelligence Officers (19 May 2003), US Coup Plotting in Iraq, Weekly Intelligence Notes 19-03, archived from the original on 9 April 2016, retrieved 3 August 2016

- ^ Ignatius, David (May 16, 2003), The CIA And the Coup That Wasn't, archived from the original on March 12, 2016, retrieved August 3, 2016

- ISBN 9788176484787.

- ^ "Winning the War on Terror" (PDF). U.S. State Department Bureau of Public Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ^ Bellinger, John. "Transatlantic Approaches to the International Legal Regime in an Age of Globalization and Terrorism". U.S. State Department. Archived from the original on 2019-12-25. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ^ UN Security Council Resolution 1441 Archived 2019-06-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 30 January 2008

- ^ United Nations Security Council PV 4701. page 2. Colin Powell United States 5 February 2003. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ^ Shakir, Faiz. "Bush Insists 'I Didn't Want War,' Overwhelming Evidence Suggests Otherwise". ThinkProgress.

- ^ Smith, R. Jeffrey (April 6, 2007). "Hussein's Prewar Ties To Al-Qaeda Discounted". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 11, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ Sandalow, Marc (September 29, 2004). "Record shows Bush shifting on Iraq war / President's rationale for the invasion continues to evolve". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ "Iraq war illegal, says Annan". BBC News. September 16, 2004. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- ^ Feller, Ben (27 February 2009). "Obama sets firm withdrawal timetable for Iraq". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009.

- ^ Cloud, David S. (19 January 2023). "WSJ News Exclusive | Iraq Economy Reels as U.S. Moves Against Money Flows to Iran". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ "Who Else, Besides Americans, Are Flying Fighter Jets in Iraq?". Slate. 8 August 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ Rampton, Roberta. "Fired: Trump dumps top lawyer who defied immigration order". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2018-10-20. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ Vora, Shivani (20 February 2017). "After Travel Ban, Interest in Trips to U.S. Declines". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-10-22. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ Jr, Donald G. Mcneil (6 February 2017). "Trump's Travel Ban, Aimed at Terrorists, Has Blocked Doctors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-10-22. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ "Iraqi Shiite militia supporters attack US embassy compound in Baghdad". France 24. 2020-12-31.

- ^ "Iraqi PM condemns US killing of Iran's Soleimani". The Straits Times. 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ article, Amos Harel 24 minutes ago This is a primium. "Middle East News". haaretz.com. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Neale, Spencer (3 January 2020). "Iraqi parliament vows to 'put an end to US presence' in country". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on 4 January 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ "Baath Party Archives Return to Iraq, With the Secrets They Contain". The Wall Street Journal. 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Threat to evacuate U.S. diplomats from Iraq raises fear of war". Reuters. 28 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

Bibliography

- Gibson, Bryan R. (2015). Sold Out? US Foreign Policy, Iraq, the Kurds, and the Cold War. ISBN 978-1-137-48711-7.

- Siracusa, Joseph M., and Laurens J. Visser, "George W. Bush, Diplomacy, and Going to War with Iraq, 2001-2003." The Journal of Diplomatic Research/Diplomasi Araştırmaları Dergisi (2019) 1#1: 1-29 online