Gazetteer

A gazetteer is a geographical

Etymology

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a "gazetteer" as a "geographical index or dictionary".[6] It includes as an example a work by the British historian Laurence Echard (d. 1730) in 1693 that bore the title "The Gazetteer's: or Newsman's Interpreter: Being a Geographical Index".[6] Echard wrote that the title "Gazetteer's" was suggested to him by a "very eminent person" whose name he chose not to disclose.[6] For Part II of this work published in 1704, Echard referred to the book simply as "the Gazeteer". This marked the introduction of the word "gazetteer" into the English language.[6] Historian Robert C. White suggests that the "very eminent person" written of by Echard was his colleague Edmund Bohun, and chose not to mention Bohun because he became associated with the Jacobite movement.[6]

Since the 18th century, the word "gazetteer" has been used interchangeably to define either its traditional meaning (i.e., a geographical dictionary or directory) or a daily newspaper, such as the London Gazetteer.[7][8]

Types and organization

Gazetteers are often categorized by the type, and scope, of the information presented. World gazetteers usually consist of an alphabetical listing of countries, with pertinent

Gazetteer editors gather facts and other information from official government reports, the

History

Western world

Hellenistic and Greco-Roman eras

In his journal article "Alexander and the Ganges" (1923), the 20th-century historian W.W. Tarn calls a list and description of satrapies of Alexander's Empire written between 324 and 323 BC as an ancient gazetteer.[9] Tarn notes that the document is dated no later than June 323 BC, since it features Babylon as not yet partitioned by Alexander's generals.[10] It was revised by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus in the 1st century BC.[10] In the 1st century BC, Dionysius of Halicarnassus mentioned the chronicle-type format of the writing of the logographers in the age before the founder of the Greek historiographic tradition, Herodotus (i.e., before the 480s BC), saying "they did not write connected accounts but instead broke them up according to peoples and cities, treating each separately".[11] Historian Truesdell S. Brown asserts that what Dionysius describes in this quote about the logographers should be categorized not as a true "history" but rather as a gazetteer.[11] While discussing the Greek conception of the river delta in ancient Greek literature, Francis Celoria notes that both Ptolemy and Pausanias of the 2nd century AD provided gazetteer information on geographical terms.[12]

Perhaps predating Greek gazetteers were those made in

...the name of a nome capital, its sacred barque, its sacred tree, its cemetery, the date of its festival, the names of forbidden objects, the local god, land, and lake of the city. This interesting codification of data, probably made by a priest, is paralleled by very similar editions of data on the temple walls at Edfu, for example.[13]

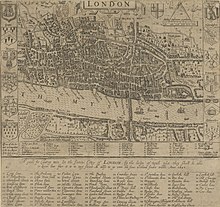

Medieval and early modern eras

The

The Italian monk Phillippus Ferrarius (d. 1626) published his geographical dictionary "Epitome Geographicus in Quattuor Libros Divisum" in the Swiss city of Zürich in 1605.[20] He divided this work into overhead topics of cities, rivers, mountains, and lakes and swamps.[20] All placenames, given in Latin, were arranged in alphabetical order for each overhead division by geographic type;.[20] A year after his death, his "Lexicon Geographicum" was published, which contained more than 9,000 different entries for geographic places.[20] This was an improvement over Ortelius' work, since it included modern placenames and places discovered since the time of Ortelius.[20]

Following the American Revolutionary War, United States clergyman and historian Jeremy Belknap and Postmaster General Ebenezer Hazard intended to create the first post-revolutionary geographical works and gazetteers, but they were anticipated by the clergyman and geographer Jedidiah Morse with his Geography Made Easy in 1784.[22] However, Morse was unable to finish the gazetteer in time for his 1784 geography and postponed it.[23] Yet his delay to publish it lasted too long, as it was Joseph Scott in 1795 who published the first post-revolutionary American gazetteer, his Gazetteer of the United States.[23] With the aid of Noah Webster and Rev. Samuel Austin, Morse finally published his gazetteer The American Universal Geography in 1797.[24] However, Morse's gazetteer did not receive distinction by literary critics, as gazetteers were deemed as belonging to a lower literary class.[25] The reviewer of Joseph Scott's 1795 gazetteer commented that it was "little more than medleys of politics, history and miscellaneous remarks on the manners, languages and arts of different nations, arranged in the order in which the territories stand on the map".[25] Nevertheless, in 1802 Morse followed up his original work by co-publishing A New Gazetteer of the Eastern Continent with Rev. Elijah Parish, the latter of whom Ralph H. Brown asserts did the "lion's share of the work in compiling it".[26]

Modern era

Gazetteers became widely popular in

East Asia

China

In

In 610 after the

Historian James M. Hargett states that by the time of the Song dynasty, gazetteers became far more geared towards serving the current political, administrative, and military concerns than in gazetteers of previous eras, while there were many more gazetteers compiled on the local and national levels than in previous eras.

While working in the

Historian

Although better known for his work on the

The

Continuing an old tradition of fangzhi, the

Korea

In

Japan

In

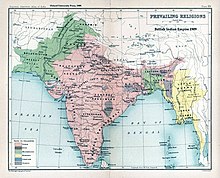

South Asia

In pre-modern

Muslim world

The pre-modern

List of gazetteers

Worldwide

Antarctica

Australia

United Kingdom

- National Land and Property Gazetteer

- National Street Gazetteer

- The Gazetteer for Scotland

- Imperial Gazetteer of Scotland

- Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales

India

See also

- List of geography topics

- Toponymy

Notes

- ^ "Gazetteer". Macmillan Dictionary. Macmillan. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Webster's dictionary and Roget's thesaurus. Paradise Press Inc. 2006. p. 68. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ISBN 1577233603. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Aurousseau, 61.

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. Gazetteer, n3. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e White, 658.

- ^ Thomas, 623–636.

- ^ Asquith, 703–724.

- ^ Tarn, 93–94.

- ^ a b Tarn, 94.

- ^ a b Brown (1954), 837.

- ^ Celoria, 387.

- ^ a b Wilson (2003), 98.

- ^ Harfield, 372.

- ^ Harfield, 373–374.

- ^ a b Ravenhill, 425.

- ^ a b Ravenhill, 424.

- ^ Ravenhill, 426.

- ^ a b c White, 657.

- ^ a b c d e White, 656.

- ^ White, 659.

- ^ Brown (1941), 153–154.

- ^ a b Brown (1941), 189.

- ^ Brown (1941), 189–190.

- ^ a b Brown (1941), 190.

- ^ Brown (1941), 194.

- ^ Aurousseau, 66.

- ^ Murphy, 113.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 406.

- ^ a b Hargett (1996), 405.

- ^ Thogersen & Clausen, 162.

- ^ Bol, 37–38.

- ^ a b Hargett (1996), 407.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 408.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 411.

- ^ Bol, 41.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 414.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 409–410.

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 3, 518.

- ^ Hsu, 90.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 409.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 410.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 412.

- ^ a b c Bol, 44.

- ^ a b Bol, 46.

- ^ Bol, 47.

- ^ a b Bol, 38.

- ^ Britnell, 237.

- ^ Schafer, 26–27.

- ^ a b Hostetler, 633.

- ^ a b Hostetler, 634.

- ^ Hostetler, 637–638.

- ^ a b c Brook, 6–7, 73, 90–93, 129–130, 151.

- ^ Brook, 28, 94–96, 267.

- ^ a b Fairbank & Teng, 211.

- ^ Wong, 44.

- ^ a b c Masuda, 18.

- ^ Masuda, 18–19.

- ^ Fairbank & Teng, 215.

- ^ Masuda, 32.

- ^ a b Masuda, 23–24.

- ^ Vermeer 440.

- ^ Thogersen & Clausen, 161–162.

- ^ a b c d Thogersen & Clausen, 163.

- ^ Vermeer, 440–443.

- ^ a b McCune, 326.

- ^ a b Provine, 8.

- ^ Lewis, 225–226.

- ^ a b Pratt & Rutt, 423.

- ^ a b Lewis, 225.

- ^ Miller, 279.

- ^ Taryō, 178.

- ^ Levine, 78.

- ^ Hall, 211.

- ^ Yasuko Makino,"Heibonsha" (entry), The Oxford Companion to the Book, oxfordreference.com. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Nihon rekishi chimei taikei (日本歴史地名大系) = Japanese Historical Place Names, ku.edu. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Gole, 102.

- ^ Baliga, 255.

- ^ Floor & Clawson, 347–348.

- ^ King, 79.

References

- Asquith, Ivon (2009). "Advertising and the Press in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 1790–1821". The Historical Journal. 18 (4): 703–724. S2CID 140975585.

- Aurousseau, M. (1945). "On Lists of Words and Lists of Names". The Geographical Journal. 105 (1/2): 61–67. JSTOR 1789547.

- Baliga, B.S. (2002). Madras District Gazetteers. Chennai: Superintendent, Government Press.

- Bol, Peter K. (2001). "The Rise of Local History: History, Geography, and Culture in Southern Song and Yuan Wuzhou". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 61 (1): 37–76. JSTOR 3558587.

- Britnell, R.H. (1997). Pragmatic Literacy, East and West, 1200–1330. Woodbridge, Rochester: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-695-9.

- ISBN 0-520-22154-0(Paperback).

- Brown, Ralph H. (1941). "The American Geographies of Jedidiah Morse". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 31 (3): 145–217. ISSN 0004-5608.

- Brown, Truesdell S. (1954). "Herodotus and His Profession". The American Historical Review. 59 (4): 829–843. JSTOR 1845119.

- Celoria, Francis (1966). "Delta as a Geographical Concept in Greek Literature". Isis. 57 (3): 385–388. S2CID 143811840.

- Fairbank, J. K.; Teng, S. Y. (1941). "On The Ch'ing Tributary System". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 6 (2): 135. JSTOR 2718006.

- Floor, Willem; Clawson, Patrick (2001). "Safavid Iran's Search for Silver and Gold". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 32 (3): 345–368. S2CID 162418783.

- Gole, Susan (2008). "Size as a measure of importance in Indian cartography". Imago Mundi. 42 (1): 99–105. JSTOR 1151051.

- Hall, John Whitney (1957). "Materials for the Study of Local History in Japan: Pre-Meiji Daimyō Records". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 20 (1/2): 187–212. JSTOR 2718525.

- Harfield, C.G. (1991). "A Hand-List of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book". The English Historical Review. 106 (419): 371–392. JSTOR 573107.

- Hargett, James M. (1996). "Song Dynasty Local Gazetteers and Their Place in The History of Difangzhi Writing". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 56 (2): 405–442. JSTOR 2719404.

- Hostetler, Laura (2008). "Qing Connections to the Early Modern World: Ethnography and Cartography in Eighteenth-Century China". Modern Asian Studies. 34 (3): 623–662. S2CID 147656944.

- Hsu, Mei‐Ling (2008). "The Qin maps: A clue to later Chinese cartographic development". Imago Mundi. 45 (1): 90–100. JSTOR 1151164.

- King, David A. (2008). "Two Iranian world maps for finding the direction and distance to Mecca". Imago Mundi. 49 (1): 62–82. JSTOR 1151334.

- Levine, Gregory P. (2001). "Switching Sites and Identities: The Founder's Statue at the Buddhist Temple Korin'in". The Art Bulletin. 83 (1): 72–104. JSTOR 3177191.

- Lewis, James B. (2003). Frontier Contact Between Choson Korea and Tokugawa Japan. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1301-8.

- Masuda, Wataru. (2000). Japan and China: Mutual Representations in the Modern Era. Translated by Joshua A. Fogel. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22840-6.

- McCune, Shannon (1946). "Maps of Korea". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 5 (3): 326–329. S2CID 134509348.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1967). "Old Japanese Phonology and the Korean-Japanese Relationship". Language. 43 (1): 278–302. JSTOR 411398.

- Murphy, Mary (1974). "Atlases of the Eastern Hemisphere: A Summary Survey". Geographical Review. 64 (1): 111–139. JSTOR 213796.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Pratt, Keith L. and Richard Rutt. (1999). Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Richmond: Routledge; Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-0463-9.

- Provine, Robert C. (2000). "Investigating a Musical Biography in Korea: The Theorist/Musicologist Pak Yon (1378–1458)". Yearbook for Traditional Music. 32: 1–15. S2CID 191402230.

- Ravenhill, William (1978). "John Adams, His Map of England, Its Projection, and His Index Villaris of 1680". The Geographical Journal. 144 (3): 424–437. JSTOR 634819.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T’ang Exotics. University of California Press. Berkeley and Los Angeles. 1st paperback edition: 1985. ISBN 0-520-05462-8.

- Tarn, W. W. (2013). "Alexander and the Ganges". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 43 (2): 93–101. S2CID 164111602.

- Taryō, Ōbayashi; Taryo, Obayashi (1984). "Japanese Myths of Descent from Heaven and Their Korean Parallels". Asian Folklore Studies. 43 (2): 171. JSTOR 1178007.

- Thomas, Peter D. G. (1959). "The Beginning of Parliamentary Reporting in Newspapers, 1768–1774". The English Historical Review. LXXIV (293): 623–636. JSTOR 558885.

- Thogersen, Stig; Clausen, Soren (1992). "New Reflections in the Mirror: Local Chinese Gazetteers (Difangzhi) in the 1980s". The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs. 27 (27): 161–184. S2CID 130833332.

- Vermeer, Eduard B. (2016). "New County Histories". Modern China. 18 (4): 438–467. S2CID 144007701.

- White, Robert C. (1968). "Early Geographical Dictionaries". Geographical Review. 58 (4): 652–659. JSTOR 212687.

- Wilson, Penelope. (2003). Sacred Signs: Hieroglyphs in Ancient Egypt. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280299-2.

- Wong, H.C. (1963). "China's Opposition to Western Science during Late Ming and Early Ch'ing". Isis. 54 (1): 29–49. S2CID 144136313.

External links

![]() Media related to Gazetteers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gazetteers at Wikimedia Commons