Illinois Country

| Pays des Illinois | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District of New France | |||||||||||||||

| 1675–1769 1801–1803 | |||||||||||||||

St Louis–after 1764) | |||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Foundation of the first mission at the Grand Village of the Illinois | 1675 | ||||||||||||||

• Transfer from French Canada to French Louisiana | 1717 | ||||||||||||||

| 1763 | |||||||||||||||

• Split east to Great Britain (Province of Quebec) | 1763 | ||||||||||||||

• East ceded to the United States | 1783 | ||||||||||||||

• Spanish retrocession of west | 1801 | ||||||||||||||

| to the United States | 1803 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||||||||

The Illinois Country (

The Illinois Country was governed from the French province of

As a consequence of the French defeat in the French and Indian War in 1764, the Illinois Country east of the Mississippi River was ceded to the British and became part of the British Province of Quebec; the land west of the river was ceded to the Spanish (Luisiana).

During the American Revolutionary War, Virginian George Rogers Clark led the Illinois campaign against the British. Illinois Country east of the Mississippi River along with what was then much of Ohio Country became part of Illinois County, Virginia, claimed by right of conquest. The county was abolished in 1782. In 1784, Virginia ceded its claims. Part of the area was incorporated in the Northwest Territory. The name lived on as Illinois Territory between 1809 and 1818, and as the State of Illinois after its admission to the union in 1818. The residual part of Illinois Country west of the Mississippi was acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

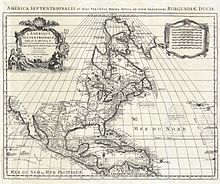

Location and boundaries

The boundaries of the Illinois Country were defined in a variety of ways, but the region now known as the

A generation later, trade conflicts between Canada and Louisiana led to a more defined boundary between the French colonies; in 1745, Louisiana governor general

This boundary between Canada and the Illinois Country remained in effect until the Treaty of Paris in 1763, after which France surrendered its remaining territory east of the Mississippi to Great Britain. (Although British forces had occupied the "Canadian" posts in the Illinois and Wabash countries in 1761, they did not occupy Vincennes or the Mississippi River settlements at Cahokia and Kaskaskia until 1764, after the ratification of the peace treaty.[8]) As part of a general report on conditions in the newly conquered lands, Gen. Thomas Gage, then commandant at Montreal, explained in 1762 that, although the boundary between Louisiana and Canada was not exact, it was understood that the upper Mississippi above the mouth of the Illinois was in Canadian trading territory.[9]

Distinctions became somewhat clearer after the

Exploration and settlement

The first French explorations of the Illinois Country were in the first half of the 17th century, led by explorers and missionaries based in Canada. Étienne Brûlé explored the upper Illinois country in 1615 but did not document his experiences. Joseph de La Roche Daillon reached an oil spring at the northeasternmost fringe of the Mississippi River basin during his 1627 missionary journey.

In 1669–70, Father

From the 1710s to the 1730s, the Fox Wars between the French, French allied tribes and the Meskwaki (Fox) Native American tribe occurred in what is now northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, and Michigan, in particular, over the fur trade. During the conflict, in what is now McLean County, Illinois, French and allied forces won a consequential battle against the Meskwaki in 1730.[13][14]

Fort St. Louis du Rocher

French explorers led by

During the earliest of the French and Indian Wars, the French used the fort as a refuge against attacks by Iroquois, who were allied with the British. The Iroquois forced the settlers, then commanded by Henri de Tonti, to abandon the fort in 1691. De Tonti reorganized the settlers at Fort Pimitoui in modern-day Peoria.

French troops commanded by

On April 20, 1769, an Illinois Confederation warrior assassinated

Fort de Chartres

On January 1, 1718, a trade monopoly was granted to

The original fort was located on the east bank of the Mississippi River, downriver (south) from Cahokia and upriver of Kaskaskia. The nearby settlement of Prairie du Rocher, Illinois, was founded by French-Canadian colonists in 1722, a few miles inland from the fort.

The fort was to be the seat of government for the Illinois Country and help to control the aggressive

The new stone fort was headquarters for the French Illinois Country for less than 20 years, as it was turned over to the British in 1763 with the

The British took control of Fort de Chartres on October 10, 1765 and renamed it

After severe flooding in 1772, the British saw little value in maintaining the fort and abandoned it. They moved the military garrison to the fort at Kaskaskia and renamed it Fort Gage. Chartres' ruined but intact magazine is considered the oldest surviving European structure in Illinois and was reconstructed in the 20th century, with much of the rest of the Fort.

Agricultural settlement and slavery

According to historian, Carl J. Ekberg, the French settlement pattern in Illinois Country was generally unique in 17th- and 18th-century French North America. These were unlike other such French settlements, which primarily had been organized in separated homesteads along a river with long rectangular plots stretching back from the river (ribbon plots). The Illinois Country French, although they marked long-ribbon plots, did not reside on them. Instead, settlers resided together in farming villages, more like the farming villages of northern France, and practiced communal agriculture.[17]

After the port of New Orleans, along the Mississippi River to the south, was founded in 1718, more African slaves were imported to the Illinois Country for use as agricultural and mining laborers. By the mid-eighteenth century, slaves accounted for as much as a third of the population.[18]

Other settlements

- In 1675,

- Fort Pimiteoui, and later Old Fort Peoria, was established in 1691.[19]French interests dominated at Peoria for well over a hundred years, from the time the first French explorers came up the Illinois River in 1673 until the first United States settlers began to move into the area around 1815. A small French presence persisted for a time on the east bank of the river, but was gone by about 1846. Today, only faint echoes of French Peoria survive in the street plan of downtown Peoria, and in the name of an occasional street, school, or hotel meeting room: Joliet, Marquette, LaSalle.

- The Chicago portagebetween 1696 and 1700.

- Peoria.

- Catholic Church of the Immaculate Conception, built in 1843 and moved brick by brick to the new location on Kaskaskia Island about 1893.

- In 1720, Africanslaves in the region. Some of the French farmers also used slaves for labor, but most families held only a few, if any. The village quickly produced an agricultural surplus, with its goods sold to lower Louisiana, as well as to settlements less successful than those in the Illinois Country, such as Arkansas Post.

- As early as 1733, a trading post was established by Jean Baptiste de Girardot at Cape Girardeau and the town later formed in 1793.

- The original French Colonialarchitecture in the US.

- The French established Fort Orleans in 1723 along the Missouri River near Brunswick, Missouri.

- Fort Sackville after their capture of it in the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War.) George Rogers Clark renamed it Fort Patrick Henry, for the Governor of Virginia, when he took it in the American Revolution. Although part of the original expansive Illinois Country, as part of the Northwest Territory, it became the seat of a separate county.

- The French built Fort de L'Ascension (later, de Massiac) on the Ohio River in 1757 near present-day Metropolis, Illinois.

- St. Louis was founded in 1764 by French fur traders. In 1765, it was made the capital of Upper Louisiana; and after 1767, control of the region west of the Mississippi was given to the Spanish ("District of Illinois"[6]). In 1780, St. Louis was attacked by British forces, mostly Native Americans, during the American Revolutionary War.[20]

British province of Quebec

Following the British occupation of the east bank of the Mississippi in 1765, some

Illinois Country under American control

During the Revolutionary War, General

For their assistance to General Clark in the war, settled Canadien and Indian residents of Illinois Country were given full citizenship. Under the Northwest Ordinance and many subsequent treaties and acts of Congress, the Canadien and Indian residents of Vincennes and Kaskaskia were granted specific exemptions, as they had declared themselves citizens of Virginia. The term Illinois Country was sometimes used in legislation to refer to these settlements.

Much of the Illinois Country region became an

See also

- French Colonial Historic District

- List of commandants of the Illinois Country

- Missouri French, a dialect of French spoken in the Midwestern Mississippi River Valley

- Ohio Country

- Slavery in New France

Notes

- ^ The Governor General of Canada (November 12, 2020). "Royal Banner of France - Heritage Emblem". Confirmation of the blazon of a Flag. February 15, 2008 Vol. V, p. 202. The Office of the Secretary to the Governor General.

- ^ New York State Historical Association (1915). Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association with the Quarterly Journal: 2nd−21st Annual Meeting with a List of New Members. The Association.

It is most probable that the Bourbon Flag was used during the greater part of the occupancy of the French in the region extending southwest from the St. Lawrence to the Mississippi, known as New France... The French flag was probably blue at that time with three golden fleur − de − lis ....

- ^ "Background: The First National Flags". The Canadian Encyclopedia. November 28, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

At the time of New France (1534 to the 1760s), two flags could be viewed as having national status. The first was the banner of France — a blue square flag bearing three gold fleurs-de-lys. It was flown above fortifications in the early years of the colony. For instance, it was flown above the lodgings of Pierre Du Gua de Monts at Île Sainte-Croix in 1604. There is some evidence that the banner also flew above Samuel de Champlain's habitation in 1608. ... the completely white flag of the French Royal Navy was flown from ships, forts and sometimes at land-claiming ceremonies.

- ^ "INQUINTE.CA | CANADA 150 Years of History ~ The story behind the flag". inquinte.ca.

When Canada was settled as part of France and dubbed "New France," two flags gained national status. One was the Royal Banner of France. This featured a blue background with three gold fleurs-de-lis. A white flag of the French Royal Navy was also flown from ships and forts and sometimes flown at land-claiming ceremonies.

- ^ Wallace, W. Stewart (1948). "Flag of New France". The Encyclopedia of Canada. Vol. II. Toronto: University Associates of Canada. pp. 350–351.

During the French régime in Canada, there does not appear to have been any French national flag in the modern sense of the term. The "Banner of France", which was composed of fleur-de-lys on a blue field, came nearest to being a national flag, since it was carried before the king when he marched to battle, and thus in some sense symbolized the kingdom of France. During the later period of French rule, it would seem that the emblem...was a flag showing the fleur-de-lys on a white ground... as seen in Florida. There were, however, 68 flags authorized for various services by Louis XIV in 1661; and a number of these were doubtless used in New France

- ^ ISBN 9780252069246. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ JSTOR 451217.

- ^ Hamelle, W.H. (1915). A Standard History of White County, Indiana. Chicago and New York: Lewis Publishing Co. p. 12. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ Shortt, Adam; Doughty, Arthur G., eds. (1907). Documents Relating to the Constitutional History of Canada, 1759-1791. Ottawa: Public Archives Canada. p. 72. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Native Americans-Historic:The Illinois-Society, The French Illinois State Museum

- ^ a b Jacques Marquette 1673 | Virtual Museum of New France Canadian Museum of History

- ^ Guy Frégault, Le Grand Marquis: Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil et la Louisiane (Montreal, 1952), pp. 129–130

- ^ Edmunds, R. David (2005). "Mesquakie (Fox)". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- )

- ^ a b "The Illinois Archaeology − Starved Rock Site". Museum Link − Illinois State Museum. 2000. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-8837-3.

- ^ Ekberg (2000), pp. 28−32

- ^ Ekberg (2000), pp. 2−3

- ^ The First European Settlement in Illinois

- ^ Usgennet.org Archived February 23, 2001, at the Wayback Machine Attack On St. Louis: May 26, 1780.

- ^ "The Illinois Society: The British". www.museum.state.il.us. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

Bibliography

- Alvord, Clarence Walworth. The Illinois Country, 1673–1818 (1920) online

- Belting, Natalia Maree, Kaskaskia under the French Regime (1948) online

- Brackenridge, Henri Marie, Recollections of Persons and Places in the West (Google Books)

- Ekberg, Carl J., Stealing Indian Women: Native Slavery in the Illinois Country, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

- Ekberg, Carl J., Francois Vallé and His World: Upper Louisiana Before Lewis and Clark, Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2002.

- Ekberg, Carl J., French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2000, ISBN 0-252-06924-2

- Ekberg, Carl J., Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier, Tucson, AZ: Patrice Press, 1996, ISBN 1-880397-14-5

- Lippincott, Isaac. "Industry among the French in the Illinois country." Journal of Political Economy 18.2 (1910): 114−128. online

External links

- French Peoria in the Illinois Country, 1673−1846 Library of Congress exhibit

- Louisiana Digital Libraries Plan for Fort Orleans