Upwelling

Upwelling is an

The increased availability of nutrients in upwelling regions results in high levels of

Mechanisms

The three main drivers that work together to cause upwelling are

Types

The major upwellings in the ocean are associated with the divergence of currents that bring deeper, colder, nutrient rich waters to the surface. There are at least five types of upwelling: coastal upwelling, large-scale wind-driven upwelling in the ocean interior, upwelling associated with eddies, topographically-associated upwelling, and broad-diffusive upwelling in the ocean interior.

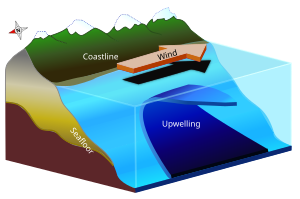

Coastal

Coastal upwelling is the best known type of upwelling, and the most closely related to human activities as it supports some of the most productive

Deep waters are rich in nutrients, including nitrate, phosphate and silicic acid, themselves the result of decomposition of sinking organic matter (dead/detrital plankton) from surface waters. When brought to the surface, these nutrients are utilized by phytoplankton, along with dissolved CO2 (carbon dioxide) and light energy from the sun, to produce organic compounds, through the process of photosynthesis. Upwelling regions therefore result in very high levels of primary production (the amount of carbon fixed by phytoplankton) in comparison to other areas of the ocean. They account for about 50% of global marine productivity.[9] High primary production propagates up the food chain because phytoplankton are at the base of the oceanic food chain.[10]

The food chain follows the course of:

- Phytoplankton →

Coastal upwelling exists year-round in some regions, known as major coastal upwelling systems, and only in certain months of the year in other regions, known as seasonal coastal upwelling systems. Many of these upwelling systems are associated with relatively high carbon productivity and hence are classified as

Worldwide, there are five major coastal currents associated with upwelling areas: the

Equatorial

Upwelling at the

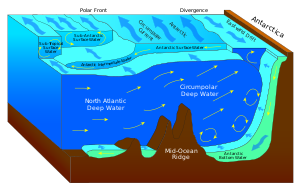

Southern Ocean

Large-scale upwelling is also found in the Southern Ocean. Here, strong westerly (eastward) winds blow around Antarctica, driving a significant flow of water northwards. This is actually a type of coastal upwelling. Since there are no continents in a band of open latitudes between South America and the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, some of this water is drawn up from great depths. In many numerical models and observational syntheses, the Southern Ocean upwelling represents the primary means by which deep dense water is brought to the surface. In some regions of Antarctica, wind-driven upwelling near the coast pulls relatively warm Circumpolar deep water onto the continental shelf, where it can enhance ice shelf melt and influence ice sheet stability.[14] Shallower, wind-driven upwelling is also found in off the west coasts of North and South America, northwest and southwest Africa, and southwest and south Australia, all associated with oceanic subtropical high pressure circulations (see coastal upwelling above).

Some models of the ocean circulation suggest that broad-scale upwelling occurs in the tropics, as pressure driven flows converge water toward the low latitudes where it is diffusively warmed from above. The required diffusion coefficients, however, appear to be larger than are observed in the real ocean. Nonetheless, some diffusive upwelling does probably occur.

Other sources

- Local and intermittent upwellings may occur when offshore islands, pelagic fisheries.[4]

- Upwelling could occur anywhere as long as there is an adequate shear in the horizontal wind field. For example when a tropical cyclone transits an area, usually when moving at speeds of less than 5 mph (8 km/h). The cyclonic winds cause a divergence in the surface water in the Ekman layer, that turn requires upwelling of deeper water to maintain continuity.[15]

- Artificial upwelling is produced by devices that use ocean wave energy or ocean thermal energy conversion to pump water to the surface. Ocean wind turbines are also known to produce upwellings.[16] Ocean wave devices have been shown to produce plankton blooms.[17]

Variations

Upwelling intensity depends on wind strength and seasonal variability, as well as the vertical structure of the water, variations in the bottom bathymetry, and instabilities in the currents.

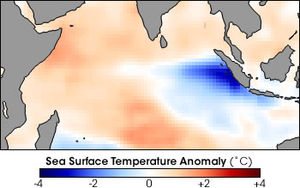

In some areas, upwelling is a

In anomalous years when the

Changes in bathymetry can affect the strength of an upwelling. For example, a submarine ridge that extends out from the coast will produce more favorable upwelling conditions than neighboring regions. Upwelling typically begins at such ridges and remains strongest at the ridge even after developing in other locations.[5]

High productivity

The most productive and fertile ocean areas, upwelling regions are important sources of marine productivity. They attract hundreds of species throughout the trophic levels; these systems' diversity has been a focal point for

Threats to upwelling ecosystems

A major threat to both this crucial intermediate trophic level and the entire upwelling trophic ecosystem is the problem of commercial fishing. Since upwelling regions are the most productive and species rich areas in the world, they attract a high number of commercial fishers and fisheries. On one hand, this is another benefit of the upwelling process as it serves as a viable source of food and income for so many people and nations besides marine animals. However, just as in any ecosystem, the consequences of over-fishing from a population could be detrimental to that population and the ecosystem as a whole. In upwelling ecosystems, every species present plays a vital role in the functioning of that ecosystem. If one species is significantly depleted, that will have an effect throughout the rest of the trophic levels. For example, if a popular prey species is targeted by fisheries, fishermen may collect hundreds of thousands of individuals of this species just by casting their nets into the upwelling waters. As these fish are depleted, the food source for those who preyed on these fish is depleted. Therefore, the predators of the targeted fish will begin to die off, and there will not be as many of them to feed the predators above them. This system continues throughout the entire food chain, resulting in a possible collapse of the ecosystem. It is possible that the ecosystem may be restored over time, but not all species can recover from events such as these. Even if the species can adapt, there may be a delay in the reconstruction of this upwelling community.[13]

The possibility of such an

Besides directly causing the collapse of the ecosystem due to their absence, this can create problems in the ecosystem through a variety of other methods as well. The animals higher in the

Another threat to the productivity and ecosystems of upwelling regions is

Effect on climate

Coastal upwelling has a major influence over the affected region's local climate. This effect is magnified if the ocean current is already cool. As the cold, nutrient-rich water moves upwards and the sea surface temperature gets cooler, the air immediately above it also cools down and is likely to condensate, forming

References

- ^ Upwelling National Ocean Service, NOAA.

- ^ .

- .

- ^ ISBN 0-632-05098-5

- ^ ISBN 1-4051-1118-6

- ^ S2CID 32516158.

- S2CID 31502815.

- .

- ^ .

- ISBN 0-7506-3384-0

- .

- ISBN 978-3-319-42524-5

- ^ .

- PMID 29109976.

- ISBN 978-1-57766-429-1.

- ^ https://wiki.met.no/_media/windfarms/brostrom_jms_2008.pdf On the influence of large wind farms on the upper ocean circulation. Göran Broström, Norwegian Meteorological Institute, Oslo, Norway

- ^ US Research project, NSF and Oregon State University Archived August 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- .

- ^ "Air-Sea interaction: Teacher's guide". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Aikayo, Ndui. "Assessment of Sea Surface Temperatures (SST) and Seasonal upwelling in SW Portugal" (PDF). University of Algarve. p. 54. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- NOAA. Retrieved 19 February 2021.