Urukagina

| Urukagina | |

|---|---|

| Reign | 24th century BC |

| Predecessor | Lugalanda |

| Successor | Lugal-zage-si |

| Dynasty | 1st Dynasty of Lagash |

| Religion | Sumerian religion |

Uru-ka-gina, Uru-inim-gina, or Iri-ka-gina (

He is best known for his reforms to combat corruption, which are sometimes cited as the first example of a

He also participated in several conflicts, notably a losing border conflict with

Reforms

Urukagina's code has been widely hailed as the first recorded example of government reform, seeking to achieve a higher level of

Despite these apparent attempts to curb the excesses of the elite class, it seems elite or royal women enjoyed even greater influence and prestige in his reign than previously. Urukagina greatly expanded the royal "Household of Women" from about 50 persons to about 1500 persons, renamed it the "Household of goddess Bau", gave it ownership of vast amounts of land confiscated from the former priesthood, and placed it under the supervision of his wife, Shasha (or Shagshag).[8] In his second year of reign, Shasha presided over the lavish funeral of his predecessor's queen, Baranamtarra, who had been an important personage in her own right.

In addition to such changes, two of his other surviving decrees, first published and translated by

Excerpt of some regulations from the Reform document

- From the border territory of Ningirsu to the sea, no person shall serve as officers.

- For a corpse being brought to the grave, his beer shall be 3 jugs and his bread 80 loaves. One bed and one lead goat shall the undertaker take away, and 3 ban [about 18 liters] of barley shall the person(s) take away.

- When to the reeds of Enki a person has been brought, his beer will be 4 jugs, and his bread 420 loaves. One barig [about 36 liters] of barley shall the undertaker take away, and 3 ban [about 18 L] of barley shall the persons of ... take away. One woman's headband, and one sila [about 1 L] of princely fragrance shall the eresh-dingir[clarification needed] priestess take away. 420 loaves of bread that have sat are the bread duty, 40 loaves of hot bread are for eating, and 10 loaves of hot bread are the bread of the table. 5 loaves of bread are for the persons of the levy, 2 mud vessels and 1 sadug[clarification needed] vessel of beer are for the lamentation singers of Girsu. 490 loaves of bread, 2 mud vessels and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the lamentation singers of Lagash. 406 loaves of bread, 2 mud vessels, and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the other lamentation singers. 250 loaves of bread and one mud vessel of beer are for the old wailing women. 180 loaves of bread and 1 mud vessel of beer are for the men of Nigin.

- The blind one who stands in ..., his bread for eating is one loaf, 5 loaves of bread are his at midnight, one loaf is his bread at midday, and 6 loaves are his bread in the evening.

- 60 loaves of bread, 1 mud vessel of beer, and 3 ban of barley are for the person who is to perform as the sagbur[clarification needed] priest, king, or god.

-

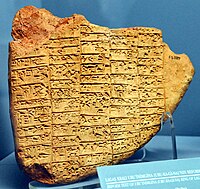

Cone fragment inscribed with part of the text of the reforms of Uruinimgina (Urukagina) - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago

-

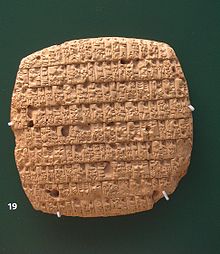

Reform cone of UrukaginaLouvre Museum

AO 3149[12] -

The Reforms of Urukagina. 20th century reconstitution.

-

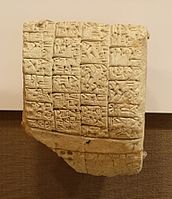

Reform text of Urukagina, king of Lagash. From Girsu, Iraq. 24th century BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul

Praise poem of Urukagina

Some insight into Sumerian values can be gained from praise poems written for kings. While the kings may not always live up to this praise they show the type of achievements that they wished to be remembered by. Extracts below praise Urukagina who appears as a social reformer, getting rid of gross abuses of power that had taken hold in Lagash.

- Since time immemorial, since life began, in those days, the head boatman appropriated boats, the livestock official appropriated asses, the livestock official appropriated sheep, and the fisheries inspector appropriated.... The shepherds of wool sheep paid a duty in silver on account of white sheep, and the surveyor, chief lamentation-singer, supervisor, brewer and foremen paid a duty in silver on account of young lambs. . . These were the conventions of former times!

- When Ningirsu, warrior of Enlil, granted the kingship of Lagash to Urukagina, selecting him from among the myriad people, he replaced the customs of former times, carrying out the command that Ningirsu, his master, had given him.

- He removed the head boatman from control over the boats, he removed the livestock official from control over asses and sheep, he removed the fisheries inspector from control....

- He removed the silo supervisor from control over the grain taxes of the guda-priests, he removed the bureaucrat responsible for the paying of duties in silver on account of white sheep and young lambs, and he removed the bureaucrat responsible for the delivery of duties by the temple administrators to the palace.

- The... administrators no longer plunder the orchards of the poor. When a high quality ass is born to a shublugal, and his foreman says to him, "I want to buy it from you"; whether he lets him buy it from him and says to him "Pay me the price I want!," or whether he does not let him buy it from him, the foreman must not strike at him in anger.

- When the house of an aristocrat adjoins the house of a shublugal, and the aristocrat says to him, "I want to buy it from you"; whether he lets him buy it from him, having said to him, "Pay me the price I want! My house is a large container—fill it with barley for me!," or whether he does not let him buy it from him, that aristocrat must not strike at him in anger.

- He cleared and cancelled obligations for those indentured families, citizens of Lagash living as debtors because of grain taxes, barley payments, theft or murder.

- Urukagina solemnly promised Ningirsu that he would never subjugate the waif and the widow to the powerful.[14]

Lament about the fall of Lagash to Umma

Urukagina participated in several conflicts, notably a losing border conflict with

"the man of

Lugal-Zage-Si himself was soon defeated and his kingdom was annexed by Sargon of Akkad.

See also

Notes

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- JSTOR 23275695.

- ISBN 978-0-429-72638-5.

- ^ "The Reforms of Urukagina". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ "Social Reform in Mesopotamia", Benjamin R. Foster, in Social Justice in the Ancient World, K. Irani and M. Silver eds., 1995, p. 169.

- ISBN 978-0-429-72638-5.

- ^ Katherine I. Wright, Archaeology and Women, 2007, p. 206.

- ^ The Powers p. 40 by Walter Wink, 1992

- ^ Marilyn French, From Eve to Dawn: A History of Women, 2008, p. 100.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Transliteration: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ Praise of Urukagina

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- JSTOR 23275695.

- ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

External links

- Reforms of Urukagina – 2015 composite Sumerian text with translation, together with editions of individual cones

- Urukagina's "reform document" (in Sumerian) A, B, C

- A partial translation in English at the Wayback Machine (archived November 17, 2018)

- "Inscriptions from the Ancient Near East" – includes a complete translation of the reform document and the lament in Italian

- "The Law Reforms of King Uru-inimgina of Lagash", pp. 8–10 in Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society by Elizabeth Meier Tetlow, 2004 – a comprehensive examination of all the ways Uruinimga's reforms both positively and adversely affected the status of women in Lagash.

- Urukagina, the reformist king. A complete description of the reign of Urukagina and his social reforms.

![Reform cone of Urukagina Louvre Museum AO 3149[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Sumerian_Cuneiform_Stone_Cone_of_Urukagina.jpg/133px-Sumerian_Cuneiform_Stone_Cone_of_Urukagina.jpg)