Vagina

| Vagina | |

|---|---|

superficial inguinal lymph nodes | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vagina |

| MeSH | D014621 |

| TA98 | A09.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 3523 |

| FMA | 19949 |

| Anatomical terminology] | |

In

Although research on the vagina is especially lacking for different animals, its location, structure and size are documented as varying among species. Female mammals usually have two external openings in the

To accommodate smoother penetration of the vagina during sexual intercourse or other

The vagina and vulva have evoked strong reactions in societies throughout history, including negative perceptions and language, cultural

Etymology and definition

The term vagina is from Latin meaning "sheath" or "scabbard".[1] The vagina may also be referred to as the birth canal in the context of pregnancy and childbirth.[2][3] Although by its dictionary and anatomical definitions, the term vagina refers exclusively to the specific internal structure, it is colloquially used to refer to the vulva or to both the vagina and vulva.[4][5]

Using the term vagina to mean "vulva" can pose medical or legal confusion; for example, a person's interpretation of its location might not match another's interpretation of the location.[4][6] Medically, one description of the vagina is that it is the canal between the hymen (or remnants of the hymen) and the cervix, while a legal description is that it begins at the vulva (between the labia).[4] It may be that the incorrect use of the term vagina is due to not as much thought going into the anatomy of the female genitals as has gone into the study of male genitals, and that this has contributed to an absence of correct vocabulary for the external female genitalia among both the general public and health professionals. Because a better understanding of female genitalia can help combat sexual and psychological harm with regard to female development, researchers endorse correct terminology for the vulva.[6][7][8]

Structure

Gross anatomy

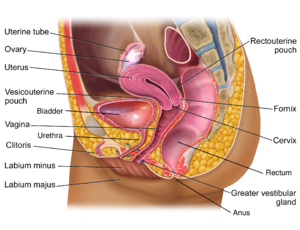

The human vagina is an elastic, muscular canal that extends from the vulva to the cervix.[9][10] The opening of the vagina lies in the urogenital triangle. The urogenital triangle is the front triangle of the perineum and also consists of the urethral opening and associated parts of the external genitalia.[11] The vaginal canal travels upwards and backwards, between the urethra at the front, and the rectum at the back. Near the upper vagina, the cervix protrudes into the vagina on its front surface at approximately a 90 degree angle.[12] The vaginal and urethral openings are protected by the labia.[13]

When not

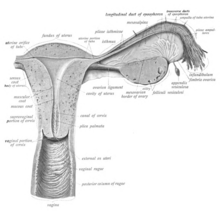

Supporting the vagina are its upper, middle, and lower third muscles and ligaments. The upper third are the

Vaginal opening and hymen

The vaginal opening (also known as the vaginal introitus)[20] is at the posterior end of the vulval vestibule, behind the urethral opening. The opening to the vagina is normally obscured by the labia minora (inner lips), but may be exposed after vaginal delivery.[10]

The

Variations and size

The length of the vagina varies among women of child-bearing age. Because of the presence of the cervix in the front wall of the vagina, there is a difference in length between the front wall, approximately 7.5 cm (2.5 to 3 in) long, and the back wall, approximately 9 cm (3.5 in) long.[10][23] During sexual arousal, the vagina expands both in length and width. If a woman stands upright, the vaginal canal points in an upward-backward direction and forms an angle of approximately 45 degrees with the uterus.[10][18] The vaginal opening and hymen also vary in size; in children, although the hymen commonly appears crescent-shaped, many shapes are possible.[10][24]

Development

The vaginal plate is the precursor to the vagina.[25] During development, the vaginal plate begins to grow where the fused ends of the paramesonephric ducts (Müllerian ducts) enter the back wall of the urogenital sinus as the sinus tubercle. As the plate grows, it significantly separates the cervix and the urogenital sinus; eventually, the central cells of the plate break down to form the vaginal lumen.[25] This usually occurs by the twenty to twenty-fourth week of development. If the lumen does not form, or is incomplete, membranes known as vaginal septae can form across or around the tract, causing obstruction of the outflow tract later in life.[25]

During sexual differentiation, without testosterone, the urogenital sinus persists as the vestibule of the vagina. The two urogenital folds of the genital tubercle form the labia minora, and the labioscrotal swellings enlarge to form the labia majora.[26][27]

There are conflicting views on the embryologic origin of the vagina. The majority view is Koff's 1933 description, which posits that the upper two-thirds of the vagina originate from the caudal part of the Müllerian duct, while the lower part of the vagina develops from the urogenital sinus.

Microanatomy

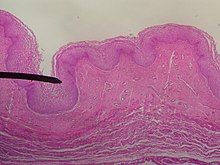

The vaginal wall from the lumen outwards consists firstly of a

The smooth muscular layer within the vagina has a weak contractive force that can create some pressure in the lumen of the vagina; much stronger contractive force, such as during childbirth, comes from muscles in the pelvic floor that are attached to the adventitia around the vagina.[35]

The lamina propria is rich in blood vessels and lymphatic channels. The muscular layer is composed of smooth muscle fibers, with an outer layer of longitudinal muscle, an inner layer of circular muscle, and oblique muscle fibers between. The outer layer, the adventitia, is a thin dense layer of connective tissue and it blends with loose connective tissue containing blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and nerve fibers that are between pelvic organs.[12][34][23] The vaginal mucosa is absent of glands. It forms folds (transverse ridges or rugae), which are more prominent in the outer third of the vagina; their function is to provide the vagina with increased surface area for extension and stretching.[9][10]

The epithelium of the ectocervix (the portion the uterine cervix extending into the vagina) is an extension of, and shares a border with, the vaginal epithelium.

Under the influence of maternal estrogen, the vagina of a newborn is lined by thick stratified squamous epithelium (or mucosa) for two to four weeks after birth. Between then to puberty, the epithelium remains thin with only a few layers of cuboidal cells without glycogen.[40][43] The epithelium also has few rugae and is red in color before puberty.[4] When puberty begins, the mucosa thickens and again becomes stratified squamous epithelium with glycogen containing cells, under the influence of the girl's rising estrogen levels.[40] Finally, the epithelium thins out from menopause onward and eventually ceases to contain glycogen, because of the lack of estrogen.[10][39][44]

Flattened squamous cells are more resistant to both abrasion and infection.

Keratinization happens when the epithelium is exposed to the dry external atmosphere.

Blood and nerve supply

Blood is supplied to the vagina mainly via the

Two main veins drain blood from the vagina, one on the left and one on the right. These form a network of smaller veins, the vaginal venous plexus, on the sides of the vagina, connecting with similar venous plexuses of the uterus, bladder, and rectum. These ultimately drain into the internal iliac veins.[15]

The nerve supply of the upper vagina is provided by the sympathetic and parasympathetic areas of the pelvic plexus. The lower vagina is supplied by the pudendal nerve.[10][15]

Function

Secretions

Vaginal secretions are primarily from the

The Bartholin's glands, located near the vaginal opening, were originally considered the primary source for vaginal lubrication, but further examination showed that they provide only a few drops of mucus.[55] Vaginal lubrication is mostly provided by plasma seepage known as transudate from the vaginal walls. This initially forms as sweat-like droplets, and is caused by increased fluid pressure in the tissue of the vagina (vasocongestion), resulting in the release of plasma as transudate from the capillaries through the vaginal epithelium.[55][56][57]

Before and during

Sexual stimulation

Nerve endings in the vagina can provide pleasurable sensations when the vagina is stimulated during sexual activity. Women may derive pleasure from one part of the vagina, or from a feeling of closeness and fullness during vaginal penetration.[60] Because the vagina is not rich in nerve endings, women often do not receive sufficient sexual stimulation, or orgasm, solely from vaginal penetration.[60][61][62] Although the literature commonly cites a greater concentration of nerve endings and therefore greater sensitivity near the vaginal entrance (the outer one-third or lower third),[61][62][63] some scientific examinations of vaginal wall innervation indicate no single area with a greater density of nerve endings.[64][65] Other research indicates that only some women have a greater density of nerve endings in the anterior vaginal wall.[64][66] Because of the fewer nerve endings in the vagina, childbirth pain is significantly more tolerable.[62][67][68]

Pleasure can be derived from the vagina in a variety of ways. In addition to

Most women require direct stimulation of the clitoris to orgasm.[61][62] The clitoris plays a part in vaginal stimulation. It is a sex organ of multiplanar structure containing an abundance of nerve endings, with a broad attachment to the pubic arch and extensive supporting tissue to the labia. Research indicates that it forms a tissue cluster with the vagina. This tissue is perhaps more extensive in some women than in others, which may contribute to orgasms experienced vaginally.[61][77][78]

During sexual arousal, and particularly the stimulation of the clitoris, the walls of the vagina lubricate. This begins after ten to thirty seconds of sexual arousal, and increases in amount the longer the woman is aroused.

An area in the vagina that may be an erogenous zone is the G-spot. It is typically defined as being located at the anterior wall of the vagina, a couple or few inches in from the entrance, and some women experience intense pleasure, and sometimes an orgasm, if this area is stimulated during sexual activity.[64][66] A G-spot orgasm may be responsible for female ejaculation, leading some doctors and researchers to believe that G-spot pleasure comes from the Skene's glands, a female homologue of the prostate, rather than any particular spot on the vaginal wall; other researchers consider the connection between the Skene's glands and the G-spot area to be weak.[64][65][66] The G-spot's existence (and existence as a distinct structure) is still under dispute because reports of its location can vary from woman to woman, it appears to be nonexistent in some women, and it is hypothesized to be an extension of the clitoris and therefore the reason for orgasms experienced vaginally.[64][67][78]

Childbirth

The vagina is the birth canal for the

As the body prepares for childbirth, the cervix softens, thins, moves forward to face the front, and begins to open. This allows the fetus to settle into the pelvis, a process known as lightening.[87] As the fetus settles into the pelvis, pain from the sciatic nerves, increased vaginal discharge, and increased urinary frequency can occur.[87] While lightening is likelier to happen after labor has begun for women who have given birth before, it may happen ten to fourteen days before labor in women experiencing labor for the first time.[88]

The fetus begins to lose the support of the cervix when contractions begin. With cervical dilation reaching 10 cm to accommodate the head of the fetus, the head moves from the uterus to the vagina.[83][89] The elasticity of the vagina allows it to stretch to many times its normal diameter in order to deliver the child.[90]

Vaginal births are more common, but if there is a risk of complications a

After giving birth, there is a phase of vaginal discharge called lochia that can vary significantly in the amount of loss and its duration but can go on for up to six weeks.[93]

Vaginal microbiota

The vaginal flora is a complex ecosystem that changes throughout life, from birth to menopause. The vaginal microbiota resides in and on the outermost layer of the vaginal epithelium.[45] This microbiome consists of species and genera, which typically do not cause symptoms or infections in women with normal immunity. The vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus species.[94] These species metabolize glycogen, breaking it down into sugar. Lactobacilli metabolize the sugar into glucose and lactic acid.[95] Under the influence of hormones, such as estrogen, progesterone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), the vaginal ecosystem undergoes cyclic or periodic changes.[95]

Clinical significance

Pelvic examinations

Vaginal health can be assessed during a pelvic examination, along with the health of most of the organs of the female reproductive system.[96][97][98] Such exams may include the Pap test (or cervical smear). In the United States, Pap test screening is recommended starting around 21 years of age until the age of 65.[99] However, other countries do not recommend pap testing in non-sexually active women.[100] Guidelines on frequency vary from every three to five years.[100][101][102] Routine pelvic examination on adult women who are not pregnant and lack symptoms may be more harmful than beneficial.[103] A normal finding during the pelvic exam of a pregnant women is a bluish tinge to the vaginal wall.[96]

Pelvic exams are most often performed when there are unexplained symptoms of discharge, pain, unexpected bleeding or urinary problems.

Lacerations or other injuries to the vagina can occur during sexual assault or other sexual abuse.[4][96] These can be tears, bruises, inflammation and abrasions. Sexual assault with objects can damage the vagina and X-ray examination may reveal the presence of foreign objects.[4] If consent is given, a pelvic examination is part of the assessment of sexual assault.[107] Pelvic exams are also performed during pregnancy, and women with high risk pregnancies have exams more often.[96][108]

Medications

Before the baby emerges from the womb, an injection for pain control during childbirth may be administered through the vaginal wall and near the pudendal nerve. Because the pudendal nerve carries motor and sensory fibers that innervate the pelvic muscles, a pudendal nerve block relieves birth pain. The medicine does not harm the child, and is without significant complications.[113]

Infections, diseases, and safe sex

Vaginal infections or diseases include

Because the vagina is self-cleansing, it usually does not need special hygiene.

The vaginal lymph nodes often trap cancerous cells that originate in the vagina. These nodes can be assessed for the presence of disease. Selective surgical removal (rather than total and more invasive removal) of vaginal lymph nodes reduces the risk of complications that can accompany more radical surgeries. These selective nodes act as sentinel lymph nodes.[49] Instead of surgery, the lymph nodes of concern are sometimes treated with radiation therapy administered to the patient's pelvic, inguinal lymph nodes, or both.[131]

Vaginal cancer and vulvar cancer are very rare, and primarily affect older women.[132][133] Cervical cancer (which is relatively common) increases the risk of vaginal cancer,[134] which is why there is a significant chance for vaginal cancer to occur at the same time as, or after, cervical cancer. It may be that their causes are the same.[134][132][135] Cervical cancer may be prevented by pap smear screening and HPV vaccines, but HPV vaccines only cover HPV types 16 and 18, the cause of 70% of cervical cancers.[136][137] Some symptoms of cervical and vaginal cancer are dyspareunia, and abnormal vaginal bleeding or vaginal discharge, especially after sexual intercourse or menopause.[138][139] However, most cervical cancers are asymptomatic (present no symptoms).[138] Vaginal intracavity brachytherapy (VBT) is used to treat endometrial, vaginal and cervical cancer. An applicator is inserted into the vagina to allow the administration of radiation as close to the site of the cancer as possible.[140][141] Survival rates increase with VBT when compared to external beam radiation therapy.[140] By using the vagina to place the emitter as close to the cancerous growth as possible, the systemic effects of radiation therapy are reduced and cure rates for vaginal cancer are higher.[142] Research is unclear on whether treating cervical cancer with radiation therapy increases the risk of vaginal cancer.[134]

Effects of aging and childbirth

Age and hormone levels significantly correlate with the pH of the vagina.

After menopause, the body produces less estrogen. This causes

Menopausal symptoms can be eased by estrogen-containing vaginal creams,

Vaginal changes that happen with aging and childbirth include mucosal redundancy, rounding of the posterior aspect of the vagina with shortening of the distance from the distal end of the anal canal to the vaginal opening,

During the third stage of labor, while the infant is being born, the vagina undergoes significant changes. A gush of blood from the vagina may be seen right before the baby is born. Lacerations to the vagina that can occur during birth vary in depth, severity and the amount of adjacent tissue involvement.

Surgery

The vagina, including the vaginal opening, may be altered as a result of surgeries such as an episiotomy,

During an episiotomy, a surgical incision is made during the second stage of labor to enlarge the vaginal opening for the baby to pass through.[45][140] Although its routine use is no longer recommended,[171] and not having an episiotomy is found to have better results than an episiotomy,[45] it is one of the most common medical procedures performed on women. The incision is made through the skin, vaginal epithelium, subcutaneous fat, perineal body and superficial transverse perineal muscle and extends from the vagina to the anus.[172][173] Episiotomies can be painful after delivery. Women often report pain during sexual intercourse up to three months after laceration repair or an episiotomy.[168][169] Some surgical techniques result in less pain than others.[168] The two types of episiotomies performed are the medial incision and the medio-lateral incision. The median incision is a perpendicular cut between the vagina and the anus and is the most common.[45][174] The medio-lateral incision is made between the vagina at an angle and is not as likely to tear through to the anus. The medio-lateral cut takes more time to heal than the median cut.[45]

Vaginectomy is surgery to remove all or part of the vagina, and is usually used to treat malignancy.[170] Removal of some or all of the sexual organs can result in damage to the nerves and leave behind scarring or adhesions.[175] Sexual function may also be impaired as a result, as in the case of some cervical cancer surgeries. These surgeries can impact pain, elasticity, vaginal lubrication and sexual arousal. This often resolves after one year but may take longer.[175]

Women, especially those who are older and have had multiple births, may choose to surgically correct vaginal laxity. This surgery has been described as vaginal tightening or rejuvenation.[176] While a woman may experience an improvement in self-image and sexual pleasure by undergoing vaginal tightening or rejuvenation,[176] there are risks associated with the procedures, including infection, narrowing of the vaginal opening, insufficient tightening, decreased sexual function (such as pain during sexual intercourse), and rectovaginal fistula. Women who undergo this procedure may unknowingly have a medical issue, such as a prolapse, and an attempt to correct this is also made during the surgery.[177]

Surgery on the vagina can be elective or cosmetic. Women who seek cosmetic surgery can have

Anomalies and other health issues

Abnormal openings known as

Society and culture

Perceptions, symbolism and vulgarity

Various perceptions of the vagina have existed throughout history, including the belief it is the center of

The word vagina is commonly avoided in conversation,

Negative views of the vagina are simultaneously contrasted by views that it is a powerful symbol of female sexuality, spirituality, or life. Author Denise Linn stated that the vagina "is a powerful symbol of womanliness, openness, acceptance, and receptivity. It is the inner valley spirit".[212] Sigmund Freud placed significant value on the vagina,[213] postulating the concept that vaginal orgasm is separate from clitoral orgasm, and that, upon reaching puberty, the proper response of mature women is a changeover to vaginal orgasms (meaning orgasms without any clitoral stimulation). This theory made many women feel inadequate, as the majority of women cannot achieve orgasm via vaginal intercourse alone.[214][215][216] Regarding religion, the womb represents a powerful symbol as the yoni in Hinduism, which represents "the feminine potency", and this may indicate the value that Hindu society has given female sexuality and the vagina's ability to deliver life;[217] however, yoni as a representation of "womb" is not the primary denotation.[218]

While, in ancient times, the vagina was often considered equivalent (

The vagina and vulva have been given many vulgar names, three of which are

In contemporary literature and art

The

In 1966, the French artist

The Vagina Monologues, a 1996 episodic play by Eve Ensler, has contributed to making female sexuality a topic of public discourse. It is made up of a varying number of monologues read by a number of women. Initially, Ensler performed every monologue herself, with subsequent performances featuring three actresses; latter versions feature a different actress for every role. Each of the monologues deals with an aspect of the feminine experience, touching on matters such as sexual activity, love, rape, menstruation, female genital mutilation, masturbation, birth, orgasm, the various common names for the vagina, or simply as a physical aspect of the body. A recurring theme throughout the pieces is the vagina as a tool of female empowerment, and the ultimate embodiment of individuality.[234][235]

Influence on modification

Societal views, influenced by tradition, a lack of knowledge on anatomy, or sexism, can significantly impact a person's decision to alter their own or another person's genitalia.[177][236] Women may want to alter their genitalia (vagina or vulva) because they believe that its appearance, such as the length of the labia minora covering the vaginal opening, is not normal, or because they desire a smaller vaginal opening or tighter vagina. Women may want to remain youthful in appearance and sexual function. These views are often influenced by the media,[177][237] including pornography,[237] and women can have low self-esteem as a result.[177] They may be embarrassed to be naked in front of a sexual partner and may insist on having sex with the lights off.[177] When modification surgery is performed purely for cosmetic reasons, it is often viewed poorly,[177] and some doctors have compared such surgeries to female genital mutilation (FGM).[237]

Female genital mutilation, also known as female circumcision or female genital cutting, is genital modification with no health benefits.[238][239] The most severe form is Type III FGM, which is infibulation and involves removing all or part of the labia and the vagina being closed up. A small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, and the vagina is opened up for sexual intercourse and childbirth.[239]

Significant controversy surrounds female genital mutilation,[238][239] with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other health organizations campaigning against the procedures on behalf of human rights, stating that it is "a violation of the human rights of girls and women" and "reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes".[239] Female genital mutilation has existed at one point or another in almost all human civilizations,[240] most commonly to exert control over the sexual behavior, including masturbation, of girls and women.[239][240] It is carried out in several countries, especially in Africa, and to a lesser extent in other parts of the Middle East and Southeast Asia, on girls from a few days old to mid-adolescent, often to reduce sexual desire in an effort to preserve vaginal virginity.[238][239][240] Comfort Momoh stated it may be that female genital mutilation was "practiced in ancient Egypt as a sign of distinction among the aristocracy"; there are reports that traces of infibulation are on Egyptian mummies.[240]

Custom and tradition are the most frequently cited reasons for the practice of female genital mutilation. Some cultures believe that female genital mutilation is part of a girl's initiation into adulthood and that not performing it can disrupt social and political cohesion.[239][240] In these societies, a girl is often not considered an adult unless she has undergone the procedure.[239]

Other animals

The vagina is a structure of animals in which the female is

Birds, monotremes, and some reptiles have a part of the

A lack of research on the vagina and other female genitalia, especially for different animals, has stifled knowledge on female sexual anatomy.[249][250] One explanation for why male genitalia is studied more includes penises being significantly simpler to analyze than female genital cavities, because male genitals usually protrude and are therefore easier to assess and measure. By contrast, female genitals are more often concealed, and require more dissection, which in turn requires more time.[249] Another explanation is that a main function of the penis is to impregnate, while female genitals may alter shape upon interaction with male organs, especially as to benefit or hinder reproductive success.[249]

Non-human

See also

- Artificial vagina

- Gynoecium

- Smegma

- Supravaginal portion of cervix

- Uterine inversion

- Vaginal dilator

- Vaginal photoplethysmograph

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3. Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-57259-171-4. Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-375-72180-9. Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-107-06429-4. Archivedfrom the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8135-7367-0. Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4684-3656-3. Archivedfrom the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-5063-2012-0. Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

Little thought apparently has been devoted to the nature of female genitals in general, likely accounting for the reason that most people use incorrect terms when referring to female external genitals. The term typically used to talk about female genitals is vagina, which is actually an internal sexual structure, the muscular passageway leading outside from the uterus. The correct term for the female external genitals is vulva, as discussed in chapter 6, which includes the clitoris, labia majora, and labia minora.

- ISBN 978-3-319-05870-2. Archivedfrom the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

In addition, there is a current lack of appropriate vocabulary to refer to the external female genitals, using, for example, 'vagina' and 'vulva' as if they were synonyms, as if using these terms incorrectly were harmless to the sexual and psychological development of women.'

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-4316-7. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-93-5152-068-9. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-323-50850-6. Archivedfrom the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-60761-915-4. Archivedfrom the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-7360-6850-5. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-8807-6. Archivedfrom the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

Because the vagina is collapsed, it appears H-shaped in cross section.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4557-1068-3. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-162087-4. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-312-2556-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4377-3648-9. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-78178-055-1. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7131-4452-9.

- ISBN 978-1-84214-199-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-443-10041-3. Archivedfrom the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974782-5. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-65457-6. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-58890-147-7.

- ISBN 978-1-60406-287-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-3-319-51257-0. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-139-48484-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ PMID 28918284.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4471-5146-3. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4757-3889-6. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-85729-757-0. Archivedfrom the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-162087-4. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4939-3099-9.

- PMID 21471299.

- ISBN 978-1-4511-5383-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-95203-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-8807-6. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-443-07477-6. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- PMID 27698617.

- ISBN 978-0-12-382032-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ISBN 978-0-470-25980-1. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ PMID 24661416.

- ISBN 978-93-5152-068-9. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84628-346-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ O'Rahilly R (2008). "Blood vessels, nerves and lymphatic drainage of the pelvis". In O'Rahilly R, Müller F, Carpenter S, Swenson R (eds.). Basic Human Anatomy: A Regional Study of Human Structure. Dartmouth Medical School. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ PMID 28848362.

- ^ "Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet". Office of Women's Health. December 23, 2014. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- OCLC 717387050.

- ISBN 978-0-321-75007-5.

- ISBN 978-1-111-57743-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7391-1385-1. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7668-1142-3. Archivedfrom the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-9194-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-135-66340-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-495-11308-9. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-6947-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-981-4516-78-5. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7614-7907-9. Archivedfrom the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-111-18663-0. Archivedfrom the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-981-4516-78-5. Archivedfrom the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4496-4851-0. Archivedfrom the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ S2CID 32381437.[permanent dead link]

- ^ ISBN 978-1-135-82509-6. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58562-905-3. Archivedfrom the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-618-75571-4. Archivedfrom the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-111-84189-8. Archivedfrom the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-337-67206-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-111-82700-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-534-62425-5. Archivedfrom the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

Most people agree that we maintain virginity as long as we refrain from sexual (vaginal) intercourse. But occasionally we hear people speak of 'technical virginity' [...] Data indicate that 'a very significant proportion of teens ha[ve] had experience with oral sex, even if they haven't had sexual intercourse, and may think of themselves as virgins' [...] Other research, especially research looking into virginity loss, reports that 35% of virgins, defined as people who have never engaged in vaginal intercourse, have nonetheless engaged in one or more other forms of heterosexual sexual activity (e.g., oral sex, anal sex, or mutual masturbation).

- ISBN 978-0-618-75571-4. Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3. Archivedfrom the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-495-81294-4. Archivedfrom the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-59233-355-4. Archivedfrom the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ S2CID 26109805.

- Sharon Mascall (June 11, 2006). "Time for rethink on the clitoris". BBC News.

- ^ PMID 22240236.

- "G-Spot Does Not Exist, 'Without A Doubt,' Say Researchers". The Huffington Post. January 19, 2012.

- "G-Spot Does Not Exist, 'Without A Doubt,' Say Researchers".

- ^ ISBN 978-1-118-60701-5. Archivedfrom the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4496-4851-0. Archivedfrom the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-305-44603-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7566-8712-0. Archivedfrom the original on May 15, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8036-2494-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4511-1702-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4698-3322-4. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ PMID 29262073.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-729-58793-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-4254-2.

- PMID 31335010.

- S2CID 247811789.

- ^ "Pregnancy Labor and Birth". Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. February 1, 2017. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-8055-1.

- PMID 23101487.

- PMID 25859220.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4496-1073-9. Archivedfrom the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-13-387640-6.

- ^ "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. February 2, 2011. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7867-5218-8. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ "CDC - Cervical Cancer Screening Recommendations and Considerations - Gynecologic Cancer Curriculum - Inside Knowledge Campaign". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ S2CID 36965456.

- PMID 22418039.

- ^ "Can Cervical Cancer Be Prevented?". American Cancer Society. November 1, 2017. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- S2CID 12370761.[Free text]

- ^ "Pelvic exam - About - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ISBN 978-981-256-906-6. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-4789-3. Archivedfrom the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ OCLC 779244257.

- ^ "Prenatal care and tests | womenshealth.gov". womenshealth.gov. December 13, 2016. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ISBN 978-1-4398-0618-0. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-323-29354-9. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- S2CID 25185650.

- ^ "The Benefits of Vaginal Drug Administration—Communicating Effectively With Patients: The Vagina: New Options for the Administration of Medications". www.medscape.org. Medscape. January 8, 2018. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7020-3120-5.

- PMID 24048183.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4496-8428-0. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-29358-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-60913-713-7. Archivedfrom the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- PMID 21251190.

- ^ "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. February 2, 2011. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4408-0135-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- PMID 12762087.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-259-58715-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61705-153-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-08373-7. Archivedfrom the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8036-4487-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-495-39192-0. Archivedfrom the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4496-8375-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-495-09185-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-312-2978-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-4354-0033-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ "Stage I Vaginal Cancer". National Cancer Institute. National Institutes of Health. February 9, 2017. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ ISBN 978-93-5025-369-4. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4408-2814-0. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c "What Are the Risk Factors for Vaginal Cancer?". American Cancer Society. October 19, 2017. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4963-5510-2. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-9512-8.

- ISBN 978-0-323-26576-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-133-41875-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-323-28781-4. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Cervical, Endometrial, Vaginal and Vulvar Cancers - Gynecologic Brachytherapy". radonc.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- PMID 28848362.

- PMID 27260082.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-84158-0. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-46132-0. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-309-29065-4. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-323-34096-0. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-182924-3.

- ISBN 978-0-323-07419-3. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8036-4490-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7637-5637-6. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-382185-0. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- OCLC 728100149.

- OCLC 894111717.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4496-8940-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-85369-576-9. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-323-29265-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4377-0756-4. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-39019-4. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84882-513-0. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-323-42810-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ PMID 28929201.

- ^ a b "Cystocele (Prolapsed Bladder) | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ "Kegel Exercises | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- S2CID 205171605.

- PMID 23836411.

- ^ OCLC 829937238.

- (PDF) from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ PMID 23152204.

- ^ S2CID 219223164.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8036-2977-6.

- S2CID 20952144.

- ^ "Episiotomy: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". Medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- OCLC 856017698.

- PMID 26894605.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-936331-5. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-118-84848-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4987-9661-3. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- PMID 15842291.

- ^ "Gender Confirmation Surgeries". American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Lawrence S Amesse (April 13, 2016). "Mullerian Duct Anomalies: Overview, Incidence and Prevalence, Embryology". Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ "Vaginal Anomalies-Pediatrics-Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-27231-3. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ISBN 978-94-017-7246-4. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-323-09161-9. Archivedfrom the original on May 15, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ISBN 978-94-017-7246-4. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ PMID 28225769.

- PMID 26528482.

- PMID 27298528.

- PMID 25062654.

- S2CID 22813363.

- PMID 26710545.

- S2CID 27012043.

- PMID 21974989.

- ^ PMID 25604504.

- ^ "Vaginal cysts: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on November 2, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- S2CID 31444644.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-2761-7. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- PMID 28379795.

- ISBN 978-0-443-06920-8. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-443-07477-6. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4557-4987-4. Archivedfrom the original on May 15, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8261-5351-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-4051-7. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-585-38424-5. Archivedfrom the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-399-52853-8. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-13-009661-6. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-4299-5522-5. Archivedfrom the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8135-3455-8.

- ISBN 978-0-670-04358-3.

The urine flows from the bladder through the urethra to the outside. Little girls often make the common mistake of thinking that they're urinating out of their vaginas. A woman's urethra is two inches long, while a man's is ten inches long.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-896836-70-6. Archivedfrom the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4299-5522-5. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-307-55955-5. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-674-54355-3. Archivedfrom the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-495-09510-1. Archivedfrom the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-59213-151-8. Archivedfrom the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-674-00613-3. Archivedfrom the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-8039-9603-8. Archivedfrom the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4. Archivedfrom the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-395-69130-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-6646-3. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-317-47678-8. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ "cunt". Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English (3rd (revised) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008.

- ^ "Definition of CUNT". Dictionary – Merriam-Webster online. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ "cunt". Merriam-Webster's Learner's Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on March 23, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-85728-500-0.

- ^ "Twat". Dictionary.com. 2015. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2015. This source aggregates material from paper dictionaries, including Random House Dictionary, Collins English Dictionary, and Harper's Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Definition of twat in English". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. British and World English lexicon. Archived from the original on June 4, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "pussy, n. and adj.2". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2007.

- JSTOR 455584.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55728-237-8. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-415-96921-5. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-312-64436-9. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ "Life & Work". nikidesaintphalle.org. 2017. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-375-50658-1. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-494-46655-1.

- ISBN 978-0-495-09185-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-571-25866-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-495-81294-4. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Female genital mutilation". Media centre. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on July 2, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85775-693-7. Archivedfrom the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2. Archivedfrom the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- doi:10.1163/156853907781476418. Archived from the original(PDF) on November 30, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- JSTOR 1379696.

- ISBN 978-3-7186-0613-9. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61731-004-1. Archivedfrom the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-521-11389-2. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ "What Is a Bird's Cloaca?". The Spruce. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ Brennan, P. L. R., Clark, C. J. & Prum, R. O. Explosive eversion and functional morphology of the duck penis supports sexual conflict in waterfowl genitalia. Proceedings: Biological Sciences 277, 1309–14 (2010).

- ^ a b c Yong E (May 6, 2014). "Where's All The Animal Vagina Research?". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ABC Online. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-100114-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-13-209727-7. Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-465-03015-6. Archivedfrom the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ISBN 978-81-312-2978-1. Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2018.