Vaginal epithelium

| Vaginal epithelium | |

|---|---|

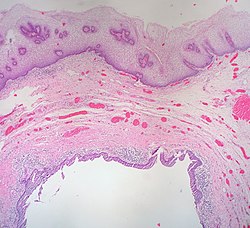

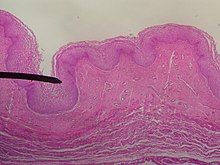

The epithelium of the vagina, visible at top, consists of multiple layers of flat cells. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Vagina |

| Anatomical terminology | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Epithelia |

|---|

|

Squamous epithelial cell |

|

Columnar epithelial cell |

|

Cuboidal epithelial cell |

| Specialised epithelia |

|

| Other |

The vaginal epithelium is the inner lining of the vagina consisting of multiple layers of (squamous) cells.[1][2][3] The basal membrane provides the support for the first layer of the epithelium-the basal layer. The intermediate layers lie upon the basal layer, and the superficial layer is the outermost layer of the epithelium.[4][5] Anatomists have described the epithelium as consisting of as many as 40 distinct layers of cells.[6][7] The mucus found on the epithelium is secreted by the cervix and uterus.[8] The rugae of the epithelium create an involuted surface and result in a large surface area that covers 360 cm2.[9] This large surface area allows the trans-epithelial absorption of some medications via the vaginal route.

In the course of the

Structure

Vaginal epithelium forms transverse ridges or rugae that are most prominent in the lower third of the vagina. This structure of the epithelium results in an increased surface area that allows for stretching.[23][24][9] This layer of epithelium is protective, and its uppermost surface of cornified (dead) cells are unique in that they are permeable to microorganisms that are part of the vaginal flora. The lamina propria of connective tissue is under the epithelium.[4][5]

Cells

| cell type | Features | Diameter | Nuclei | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| basal cell | round to cylindrical, narrow basophilic cytoplasmic space | 12-14 μm | distinct, 8–10 μm in size | only in case of severe epithelial atrophy and in repair processes after inflammation |

| stratum granulosum | part of the parabasal layer, round to longitudinal oval, cytoplasm basophilic | 20 μm | clear cell nucleus | Frequent glycogen storage, thickened cell margins and decentralized cell nucleus; Predominant cell type in menopausal women[12][24][16][20] |

| stratum spinosum | part of the parabasal layer | [20][16][24] | ||

| intermediate cell | oval to polygonal, cytoplasm basophilic | 30–50 μm | approx. 8 μm, decreasing core-plasma relation with increase in size | in pregnancy: barge-like with thickened cell margin ("navicular cells") |

| superficial squamous flat cells

|

polygonal, baso- or eosinophilic, transparent, partially keratohyaline granule | 50–60 microns | vesicular and slightly stainable or shrunken | [24][16] |

| stratum corneum | exfoliate, slough off | become detached from the epithelium | [18][19][17] |

Basal cells

The basal layer of the epithelium is the most mitotically active and reproduces new cells.[18] This layer is composed of one layer of cuboidal cells lying on top of the basal membrane.[7]

Parabasal cells

The parabasal cells include the stratum granulosum and the stratum spinosum.

Intermediate cells

Intermediate cells make abundant glycogen and store it.[26][27] Estrogen induces the intermediate and superficial cells to fill with glycogen.[19][28] The intermediate cells contain nuclei and are larger than the parabasal cells and more flattened. Some have identified a transitional layer of cells above the intermediate layer.[7]

Superficial cells

Estrogen induces the intermediate and superficial cells to fill with glycogen.[19][28] Several layers of superficial cells exist that consist of large, flattened cells with indistinct nuclei. The superficial cells are exfoliated continuously.[7]

Cell junctions

The junctions between epithelial cells regulate the passage of molecules, bacteria and viruses by functioning as a physical barrier.

Mucus

The vagina itself does not contain

Development

The epithelium of the vagina originates from three different precursors during embryonic and fetal development. These are the vaginal squamous epithelium of the lower vagina, the columnar epithelium of the endocervix, and the squamous epithelium of the upper vagina. The distinct origins of vaginal epithelium may impact the understanding of vaginal anomalies.[32] Vaginal adenosis is a vaginal anomaly traced to displacement of normal vaginal tissue by other reproductive tissue within the muscular layer and epithelium of the vaginal wall. This displaced tissue often contains glandular tissue and appears as a raised, red surface.[27]

Cyclic variations

During the luteal and follicular phases of the estrous cycle the structure of the vaginal epithelium varies. The number of cell layers vary during the days of the estrous cycle:

Day 10, 22 layers

Days 12-14, 46 layers

Day 19, 32 layers

Day 24, 24 layers

The glycogen levels in the cells is at its highest immediately before ovulation.[7]

Lytic cells

Without estrogen, the vaginal epithelium is only a few layers thick. Only small round cells are seen that originate directly from the basal layer (

Epithelial microbiota

Low pH is necessary to control vaginal microbiota. Vaginal epithelial cells have a relatively high concentration of glycogen compared to other epithelial cells of the human body. The metabolism of this complex sugar by the lactobacillus dominated microbiome is responsible for vaginal acidity.[34][35][36]

Function

The

Clinical significance

Disease transmission

Sexually transmitted infections, including HIV are rarely transmitted across intact and healthy epithelium. These protective mechanisms are due to frequent exfoliation of the superficial cells, low pH, and innate and acquired immunity in the tissue. Research into the protective nature of the vaginal epithelium has been recommended as it would help in the design of topical medication and microbicides.[9]

Cancer

There are very rare malignant growths that can originate in the vaginal epithelium.[37] Some are only known through case studies. They are more common in older women.[38]

- squamous cells of the epithelium.[37]

- Vaginal adenocarcinoma arises from secretory cells in the epithelium[37]

- Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina arises in response to prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol[39][40]

- Vaginal melanoma arises from melanocytes in the epithelium[41]

Inflammation

- Candida vaginitis is a fungal infection; the discharge is irritating to the vagina and the surrounding skin.[42]

- Bacterial vaginosis Gardnerella usually causes a discharge, itching, and irritation.[43][44]

- Aerobic vaginitis thinned reddish vaginal epithelium, sometimes with erosions or ulcerations and abundant yellowish discharge[45]

Atrophy

The vaginal epithelium changes significantly when estrogen levels decrease at menopause.[46] Atrophic vaginitis[47] usually causes scant odorless discharge[48]

History

The vaginal epithelium has been studied since 1910 by a number of histologists.[32]

Research

The use of nanoparticles that can penetrate the cervical mucus (present in the vagina) and vaginal epithelium has been investigated to determine if medication can be administered in this manner to provide protection from infection of the Herpes simplex virus.[49] Nanoparticle drug administration into and through the vaginal epithelium to treat HIV infection is also being investigated.[50]

See also

References

- ISBN 9781451153835.

- )

- ISBN 9789401181402.

- ^ ISBN 978-0857297570. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-0191620874. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- PMID 24661416.

- ^ ISBN 9789401181402.

- ^ ISBN 9781506209463.

- ^ PMID 24661416.

- ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-642-95584-6)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ ISBN 9781451153835.

- ^ "Vaginal Cytology: Introduction and Index". www.vivo.colostate.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ^ PMID 21471299.

- ISBN 9789351520689.

- ^ ISBN 978-1451153835. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0781788076.

- ^ ISBN 9780387952031.

- ^ ISBN 978-0443074776. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ ISBN 9780080919324.

- ISBN 9780387952031.

- PMID 25547201.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-4316-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-9351520689.

- ISBN 978-0-12-382032-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8.

- ^ ISBN 9781608312597.

- ^ PMID 27698617.

- ^ a b "NFP Quick Instructions for the Marquette Model (Mucus Only)". Marquette University. 2018.

- PMID 26443453.

- ISBN 9780387280363.

- ^ S2CID 3060493.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7.

- PMID 11518895.

- ^ Linhares, I. M., P. R. Summers, B. Larsen, P. C. Giraldo, and S. S. Witkin. 2011. Contemporary perspectives on vaginal pH and lactobacilli" Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 204:120.e1-120.e5.

- PMID 2237129.

- ^ a b c "Vaginal Cancer Treatment". National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ "Vaginal cancer | Vaginal cancer | Cancer Research UK". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ "About DES". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ "Known Health Effects for DES Daughters". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- PMID 28064232.

- ^ "Vaginal yeast infections fact sheet". womenshealth.gov. December 23, 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- PMID 24390920.

- ^ "Bacterial Vaginosis Symptoms, Treatment, Causes & Remedies". eMedicineHealth. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- S2CID 7789770.

- ^ Vulvovaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis have been the preferred terms for this condition and cluster of symptoms until recently. These terms are now regarded as inaccurate in describing changes to the whole genitourinary system occurring after menopause. The term atrophic vaginitis suggests that the vaginal is inflamed or infected. Though this may be true, inflammation and infection are not the major components of postmenopausal changes to the vagina after menopause. The former terms do not describe the negative effects on the lower urinary tract which can be the most troubling symptoms of menopause for women.

- PMID 26357643.

- PMID 29202940.

- ^ Greenemeier, Larry. "Small Comfort: Nanomedicine Able to Penetrate Bodily Defenses". Scientific American. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- PMID 29424324.

External links

Media related to Vaginal epithelium at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vaginal epithelium at Wikimedia Commons