Vasilisa the Beautiful

Vasilisa the Beautiful (

Synopsis

By his first wife, a merchant had a single daughter, who was known as Vasilisa the Beautiful. When the girl was eight years old, her mother died; when it became clear that she was dying, she called Vasilisa to her bedside, where she gave Vasilisa a tiny, wooden, one-of-a-kind

After the

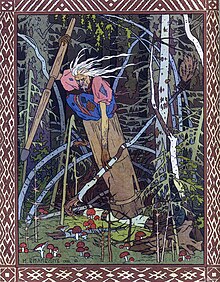

One day, the merchant had to embark on an extended journey out of town for business. His wife, seeing an opportunity to dispose of Vasilisa, sold the house on the same day he left and moved them all away to a gloomy hut by a forest where rumour said that Baba Yaga resided. When not over-working Vasilisa with housework, the step-mother would also send her out deep into the woods on superfluous errands, with the intentions of either marring her step-daughter's enduring beauty or increasing the chances of Baba Yaga discovering her and eating her, keeping the step-mother's hands clean of any perceived culpability. Only thanks to the doll was Vasilisa able to keep completing the housework and remain safe whenever out of the house, always returning unharmed. The step-mother, only becoming frustrated with how her step-daughter's continued luck, not only in remaining alive, but also in how Vasilisa's beauty continued to grow, decided to change tactics. One night, before bed, she gave each of the girls a task and put out all the fires except a single candle. Her older daughter then put out the candle (as instructed by her mother), whereupon the step-sisters bodily forced Vasilisa out of the house and demanded that she go to fetch light from Baba Yaga's hut.

The doll advised her to go, and she went. While she was walking, a mysterious man rode by her in the hours before dawn, dressed in white, riding a white horse whose equipment was all white; then a similar rider in red. She came to a house that stood on chicken legs and was walled by a fence made of human bones. A black rider, like the white and red riders, rode past her, and night fell, whereupon the eye sockets of the skulls in the fence began to glow like lanterns. Vasilisa was too frightened to run away, and so Baba Yaga found her when she arrived in her giant, flying mortar. Once she learned why the girl was there, Baba Yaga said that Vasilisa must perform tasks to earn the fire, or be killed; she was to clean the house and yard, wash Baba Yaga's laundry, and cook her a meal enough for a dozen (which Baba Yaga ate all by herself). She was also required to separate grains of rotten corn from sound corn, and separate poppy seeds from grains of soil. Baba Yaga left the hut for the day and Vasilisa despaired, as she worked herself into exhaustion. When all hope of completing the tasks seemed lost, the doll whispered that she would complete the tasks for Vasilisa, and that the girl should sleep.

At dawn, the white rider passed; at or before noon, the red. As the black rider rode past, Baba Yaga returned and could complain of nothing. She bade three pairs of disembodied hands seize the corn to squeeze the oil from it, then asked Vasilisa if she had any questions.

Vasilisa asked about the riders' identities and was told that the white one was Day, the red one the Sun, and the black one Night. But when Vasilisa thought of asking about the disembodied hands, the doll quivered in her pocket. Vasilisa realized she should not ask, and told Baba Yaga she had no further questions. In return, Baba Yaga enquired as to the cause of Vasilisa's success. On hearing the answer "by my mother's blessing", Baba Yaga, who wanted nobody with any kind of blessing in her presence, threw Vasilisa out of her house, and sent her home with a skull-lantern full of burning coals, to provide light for her step-family.

Upon her return, Vasilisa found that, since sending her out on her task, her step-family had been unable to light any candles or fire in their home. Even lamps and candles that might be brought in from outside were useless for the purpose, as all were snuffed out the second they were carried over the threshold. The coals brought in the skull-lantern burned Vasilisa's stepmother and stepsisters to ashes, and Vasilisa buried the skull according to its instructions, so no person would ever be harmed by it.[2]

Later, Vasilisa became an assistant to a maker of cloth in Russia's capital city, where she became so skilled at her work that the Tsar himself noticed her skill; he later married Vasilisa.

Analysis

Tale type

Russian scholarship classifies the tale as type 480В*, "Мачеха и падчерица" ("Stepmother and Step-daughter"), of the

Variants

In some versions, the tale ends with the death of the stepmother and stepsisters, and Vasilisa lives peacefully with her father after their removal. This lack of a wedding is unusual in a tale with a grown heroine, although some, such as Jack and the Beanstalk, do feature it.[5]

According to Jiří Polívka, in a Slovak tale from West Hungary, the heroine meets a knight or lord clad in all red, riding a red horse, with a red bird on his hand and red dog by his side. She also meets two similarly dressed lords: one in all white, and the other in all black. The heroine's stepmother explains that the red lord was the Morning, the white lord the Day and the black lord the Night.[6]

Interpretations

In common with many folklorists of his day, Alexander Afanasyev regarded many tales as primitive ways of viewing nature. In such an interpretation, he regarded this fairy tale as depicting the conflict between the sunlight (Vasilisa), the storm (her stepmother), and dark clouds (her stepsisters).[7]

Related and eponymous works

Edith Hodgetts included an English translation of this story, as Vaselesa the Beautiful in her 1890 collection Tales and Legends from the Land of the Tzar.[8]

The story is also part of a collection of Russian fairy tales titled Vasilisa The Beautiful: Russian Fairy Tales published by Raduga Publishers first in 1966. The book was edited by Irina Zheleznova, who also translated many of the stories in the book from the Russian including Vasilisa The Beautiful. The book was also translated in Hindi and Marathi.

The 1998 feminist fantasy anthology

Vasilisa appears in the 2007

A graphic version of the Vasilisa story, drawn by Kadi Fedoruk (creator of the webcomic Blindsprings), appears in Valor: Swords, a comic anthology of re-imagined fairy tales that pays homage to the strength, resourcefulness, and cunning of female heroines in fairy tales through recreations of time-honored tales and brand new stories, published by Fairylogue Press in 2014 following a successful Kickstarter campaign.

The novel Vassa in the Night by Sarah Porter is based on this folktale with a modern twist.[10]

The book Vasilisa the Terrible: A Baba Yaga Story flips the script by painting Vasilisa as a villain and Baba Yaga as an elderly woman who is framed by the young girl.[11][12]

In Annie Baker's 2017 play The Antipodes, one of the characters, Sarah, tells a story from her childhood that is reminiscent of the story of Vasilisa.

The book series Vampire Academy by Richelle Mead features a supporting character named Vasilisa, and is mentioned that she was named after Vasilisa from Vasilisa the Beautiful.

The Winternight trilogy by Katherine Arden, beginning with "The Bear and the Nightingale" is a retelling of this story.

Vasilisa (along with her doll) appears as a minor character in Alexander Utkin's graphic novels Gamayun Tales I (2019) and a major character in Gamayun Tales II (2020), although both volumes leave her story as cliffhangers for the next volume.[13]

See also

- Fairer-than-a-Fairy

- Folklore of Russia

- Vasilisa (name)

- The Two Caskets

- Cinderella

- Babushka's Doll by Patricia Polacco

- The Kind and the Unkind Girls(ATU 480)

References

- ^ Alexander Afanasyev, Narodnye russkie skazki, "Vasilissa the Beautiful" Archived 2013-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 9781475236019.

- ^ Barag, Lev. "Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка". Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. p. 142.

- ^ Haney, Jack V., ed. “COMMENTARIES.” In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume I. University Press of Mississippi, 2014. p. 501. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ISBN 0-691-06943-3

- ^ Polívka, Georg. "Personifikationen von Tag und Nacht im Volkmärchen". In: Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 26 (1916): 315.

- ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^ Hodgetts, Edith M. S. Tales and Legends from the Land of the Tzar: Collection of Russian Stories. Griffith Farran & Co. 1891. pp. 1-13.

- ^ James Graham, "Baba Yaga in Film[usurped]"

- ISBN 9780765380548.

- ISBN 9781980441618.

- ^ "Goodreads".

- ^ Utkin, Alexander. Gamayun Tales I. London: Nobrow Press, 2019; Gamayun Tales II. London: Nobrow Press, 2020.

Further reading

- Добровольская, В. Е. "Хам и Калёные зубы: имена персонажей сказки сюжетного типа СУС-480В*". In: Этнолингвистика. Ономастика. Этимология : материалы V Международной научной конференции (Екатеринбург, 7–11 сентября 2022 г.). Екатеринбург: Издательство Уральского университета, 2022. pp. 108-112. URL: http://elar.urfu.ru/handle/10995//116955.

- САМОЙЛОВА, ЕЛЕНА ВАЛЕРЬЕВНА [SAMOYLOVA, ELENA]. "ЖЕНСКИЕ РУКОДЕЛИЯ В КОНТЕКСТАХ ВОСТОЧНОСЛАВЯНСКИХ СКАЗОК" [FEMALE HANDICRAFTS IN THE CONTEXT OF EASTSLAVIC FOLK-TALES]. In: "ТРАДИЦИОННАЯ КУЛЬТУРА" 3 (67), 2017. pp. 84-96. ISSN 2410-6658.