Vasily Vereshchagin

Vasily Vereshchagin | |

|---|---|

| Василий Верещагин | |

Lüshunkou, China) | |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Alma mater | St. Petersburg Academy of Arts |

| Occupations |

|

| Style | Realist |

| Awards | Order of St. George (4th Class) |

Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin (

Years of apprenticeship

Vereshchagin was born at

Vereshchagin graduated first in his list at the naval school, but left the service immediately to begin the study of drawing in earnest. Two years later, in 1863, he won a medal from the St Petersburg Academy for his Ulysses Slaying the Suitors. In 1864, he proceeded to Paris, where he studied under Jean-Léon Gérôme, though he dissented widely from his master's methods.[2]

Travels in Central Asia

In the

In 1871, Vereshchagin established an atelier in Munich. He gave a solo exhibition of his works (later referred to as his "Turkestan Series") at the Crystal Palace in London in 1873. He gave another exhibition of his works in St Petersburg in 1874, where two of his paintings, namely, The Apotheosis of War, dedicated "to all conquerors, past, present and to come," and Left Behind, the picture of a dying soldier deserted by his fellows,[2] were denied a showing on the grounds that they portrayed the Russian military in a poor light.

In late 1874, Vereshchagin departed for an extensive tour of the Himalayas, India and Tibet, spending over two years in travel. He returned to Paris in late 1876.

- The early works

-

Portrait of bacha (1867–1868)

-

Lully (Gypsy) (1867–1868)

-

Portrait of a man in a white turban (1867)

-

Uzbekboy (1867–1868)

-

Dervishes in festive outfits (1869–1870)

-

Kalmyk chapel (1869–1870)

-

The Apotheosis of War (1871)

-

Sale of a child-slave (1872)

-

Mullah Rahim and Mullah Kerim on his way to the bazaar are quarreling (1873)

-

Main Street in Samarkand, from the height of the citadel in the early morning (1869–1870)

-

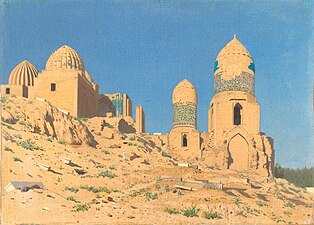

Shah-i-Zinda Mausoleum in Samarkand (1869–1870)

-

Gur-e-Amir mausoleum. Samarkand (1869–1870)

-

They are triumphant (1872).Emir of Bukharaand the city's notables watch how the heads of Russian soldiers are impaled on poles.

-

Presentation of the trophies (1872)

-

Fakir (1874–1876). A painting of an Indian fakir

-

Buddhist Temple inDarjiling. Sikkim(1874)

-

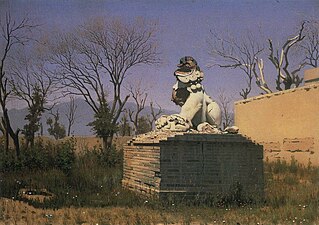

Ruins of Chinese sanctuary. Ak-Kent (1869–1870)

-

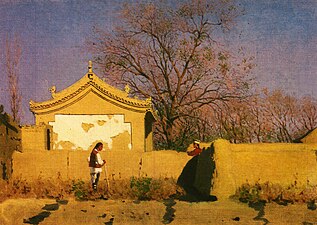

Chinese house (1869–1870)

-

Ruins of a Theater in Chuguchak (1869–1870)

-

A Garden gate in Chuguchak (1869–1870)

-

Ruins in Chuguchak (1869–1870)

-

Ruins in Chuguchak (1869–1870)

-

Chinese tent (1869–1870)

-

Afghan (1868)

-

Afghan (1869–1870)

-

After a success (1868)

-

After an unsuccess (1868)

-

A rich Kyrgyz hunter with a falcon (1871)

-

Kyrgyz yurts on theChu River(1869–1870)

-

Inside the Tent of a Rich Kirghiz (1869–1870)

-

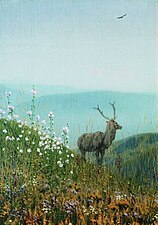

In the Alatau Mountains (1869–1870)

-

In the Alatau Mountains (1869–1870)

-

Nomadic road in the Alatau Mountains (1869–1870)

-

Kyrgyz migration (1869–1870)

-

Barskaun Passage (1869–1870)

-

The children of the Solon tribe (1869–1870)

-

Timur's (Tamerlane's) doors (1872)

-

Opium-eaters (1868)

-

Polititians in opium shop. Tashkent (1870)

-

By the Fortress Wall. "Let Them Enter" (1871)

-

Surprise Attack (1871)

Russo-Turkish War

With the start of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), Vereshchagin left Paris and returned to active service with the Imperial Russian Army. He was present at the crossing of the Shipka Pass and at the Siege of Plevna, where his brother was killed. He was dangerously wounded during the preparations for the crossing of the Danube near Rustchuk. At the conclusion of the war, he acted as secretary to General Skobelev at San Stefano.[2]

World fame

After the war, Vereshchagin settled in Munich, where he produced his war pictures so rapidly that he was freely accused of employing assistants. The sensational subjects of his pictures, and their didactic aim, namely, the promotion of peace by a representation of the horrors of war, attracted a large section of the public not usually interested in art to the series of exhibitions of his pictures in Paris in 1881 and subsequently in London, Berlin, Dresden, Vienna and other cities.[2]

Vereshchagin painted several scenes of imperial rule in

He aroused much controversy by his series of three pictures: firstly, of a Roman execution (the Crucifixion by the Romans (1887)); secondly,

By the late 19th century, Vereshchagin had gained popularity, not only in Russia, but also abroad and his name never left the pages of the European and American press. From his earliest works, unlike most contemporary battle pieces depicting war as a kind of parade, Vereshchagin graphically depicted the horrors of war. "I loved the sun all my life, and wanted to paint sunshine. When I happened to see warfare and say what I thought about it, I rejoiced that I would be able to devote myself to the sun once again. But the fury of war continued to pursue me". Vereshchagin wrote. One day, in 1882, Vereshchagin's exhibition in Berlin was visited by German field marshal Helmuth von Moltke the Elder. Vereshchagin brought Moltke to his painting The Apotheosis of War. The picture evoked a sort of confusion in the field marshal. After his visit to the exhibition, Moltke issued an order forbidding German soldiers to visit it. The Austrian war minister did the same. He also declined the artist's offer to let Austrian officers see his pictures free of charge at the 1881 exhibition in Vienna.[citation needed]

In Russia, a ban on exhibitions of Vereshchagin's work was also enforced, as well as a ban on reproductions of them in books and periodicals amidst accusations of slandering the Russian army. The artist took these unjust accusations badly and burned three of his paintings, The Forgotten Soldier, They Have Encircled, and Pursue and They Entered.[citation needed]

A journey in Syria and Palestine in 1884 furnished him with an equally discussed set of subjects from the New Testament.[2] Vereshchagin's paintings caused controversy over his portrayal of the figure of Christ with what was thought at the time to be an unseemly realism. His depiction of Jesus's features was thought to be excessively vulgar and over-emphatically Semitic in ethnicity.[citation needed]

The "1812" series on

Last years

Vereshchagin was in the Far East during the

During the

Legacy

- The town of Lyudmila Zhuravlyova in 1978.[10]

- Vereshchagin Street in Cherepovets is named after Vasily Vereshchagin, also there are a historic house museum and a monument to Vereshchagin in Cherepovets.

- He is a distant relative of the Czech rock singer Aleš Brichta. The Apotheosis of War was used by Czech heavy metal band Arakain as the cover art for the album Farao.

Gallery

- Napoleon. 1812

-

The end of Borodino battle

-

Before Moscow waiting for the Boyars' Deputation

-

Through the fire

-

In Petrovsky Palace (Waiting for peace)

-

Vereshchagin with his wife Lydia and son Vasily at the In Petrovsky Palace painting. 1895–1896

-

Napoleon and general Lauriston (Peace at all costs!)

-

On the high road. Retreat, flight

-

Fix Bayonets! Hooray! Hooray! (the Battle of Krasnoi[11])

-

Night Bivouac of Great Army

- Balkan series

-

Victors

-

Before the attack. At Plevna

-

After the Attack

-

The battlefield at Shipka (Skobelev at Shipka)

-

Defeated. Requiem

-

The Spy

-

Picket on the Danube

-

Two hawks (Bashi-bazouk)

-

In a Turkish mortuary

- Other works

-

The Moscow Cathedrals andriver Moskva(in the spring)

-

Sher-Dor Madrasa on Registan Square in Samarkand

-

Japanese woman

-

Portrait of Nadezhda Pavlovna Bogolyubova, Alexey Bogolyubov's wife

See also

Further reading

- Verestchagin, Vassili (1887). Vassili Verestchagin, Painter, soldier, Traveler; Autobiographical Sketches. Vol. 1. Translated by Peters, F. H. London: Richard Bentley & Son. Retrieved 14 August 2018 – via Internet Archive.; Verestchagin, Vassili (1887). Vassili Verestchagin, Painter, soldier, Traveler; Autobiographical Sketches. Vol. 2. Translated by Peters, F. H. London: Richard Bentley & Son. Retrieved 14 August 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Verestchagin, Vassili (1889–1890). Realism. Translated by Mrs. MacGahan. Special Exhibition; Inter-state Industrial Exposition of Chicago. Retrieved 14 August 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Verestchagin, Vassili (1899). "1812" Napoleon I in Russia; with an Introduction by R. Whiteing. London: William Heinemann. Retrieved 14 August 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Pleshakov, Constantine. "The Tsar's Last Armada-The Epic Voyage to the Battle of Tsushima." (2002).

Notes

- ^ Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, p. 408.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1021.

- ^ Heather S. Sonntag, Tracing the Turkestan Series – Vasily Vereshchagin's Representations of Late-19th-century Central Asia, University of Wisconsin-Madison (2003), p. 18

- ^ Vladimir Visson, Portraits of Russian Painters, V. Visson (1987), p. 72

- ^ Chitralekha (2020-06-02). "The 'Jaipur Procession' that inspired the world's second largest oil painting". The Heritage Lab. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ Basu, Anasuya (2022-09-04). "War Painter: Russia attacks Ukraine: time to remember a 19th century Russian artist Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin". The Telegraph Online. Retrieved 2023-12-04.

- ^ "Art in December: M. Verestchagin on his Critics – Art and Politics". The Magazine of Art. November 1887 – October 1888. 11. Cassell: ix (following p. 430). 1878–1904.

- ^ Verestchagin, Vassili (1899). "1812" Napoleon I in Russia; with an Introduction by R. Whiteing. London: William Heinemann. Retrieved 14 August 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "State Historical Museum Opens 'The Year 1812 in the Paintings by Vasily Vereshchagin'," Art Daily, March 11, 2010; "War Lasted 18 Months ... Russian Miscalculation," New York Times, August 30, 1905.

- ^ Directory of Minor Plant Names.

- ^ "Василий Васильевич Верещагин, цикл полотен «1812 год»". www.museum.ru. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Vereshchagin, Vassili Vassilievich". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1021.

- ISBN 0-8108-4927-5

- Leonard D. Abbott, "Verestchagin, Painter of War." The Comrade (New York), vol. 1, no. 7 (April 1902), pp. 155–156.

- Art Institute of Chicago, Works of Vassili Verestchagin: an Illustrated, descriptive catalogue and two appendixes to the catalogue Realism and Progress in Art by Verestchagin.

- W. T. Stead, "Vassili Verestchagin: Character Sketch," Review of Reviews (London), vol. 19 (January 1899), frontispiece, 22–33.

- Maria Chernysheva, "The Russian Gérôme? Vereshchagin as a Painter of Turkestan," RIHA Journal, September 2014.

External links

Media related to Vasily Vereshchagin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vasily Vereshchagin at Wikimedia Commons- Vereshchagin page at Olga's Gallery

- Vasily Vereshchagin: horrors of war through artist’s eyes

- Vereshchagin's lost paintings Archived 2008-12-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Works by Vasily Vereshchagin at Project Gutenberg

- Artworks by or after Vasily Vereshchagin at the Art UK site

![Oirat (Kalmyk) lama [ru] wearing a ritual headdress (1869–1870)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/%D0%9E%D0%B9%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%82%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%28%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%BC%D1%8B%D1%86%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9%29_%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B0.jpg/181px-%D0%9E%D0%B9%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%82%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%28%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%BC%D1%8B%D1%86%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9%29_%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B0.jpg)

![Barskaun Passage [ky] (1869–1870)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7a/%D0%9F%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%85%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%91%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%83%D0%BD.jpg/315px-%D0%9F%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%85%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%91%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%83%D0%BD.jpg)

![Fix Bayonets! Hooray! Hooray! (the Battle of Krasnoi[11])](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3d/The_Attack_by_Vereshchagin_%281887-1895%2C_GIM%29.jpg/136px-The_Attack_by_Vereshchagin_%281887-1895%2C_GIM%29.jpg)