Vichy France

French State État français (French) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1940–1944[1] | ||

| Motto: " Travail, Famille, Patrie" ("Work, Family, Fatherland") | ||

| Anthem: "La Marseillaise" (official) "Maréchal, nous voilà !" (unofficial)[2] ("Marshal, here we are!") | ||

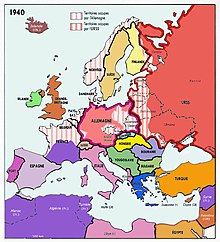

The French State in 1942:

| ||

The gradual loss of all Vichy territory to Free France and the Allied powers | ||

| Status |

| |

| Capital | ||

| Capital-in-exile | authoritarian dictatorship | |

| Chief of State | ||

• 1940–1944 | Philippe Pétain | |

| Prime Minister | ||

• 1940–1942 | Philippe Pétain | |

• 1940 (acting) | Pierre Laval | |

• 1940–1941 (acting) | P.É. Flandin | |

• 1941–1942 (acting) | François Darlan | |

• 1942–1944 | Pierre Laval | |

| Legislature | German retreat | Summer 1944 |

| 9 August 1944[1] | ||

• Capture of the Sigmaringen enclave | 22 April 1945 | |

| Currency | French franc | |

| ||

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

Vichy France (French: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State (État français), was the French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. It was named after its seat of government, the city of Vichy. Officially independent, but with half of its territory occupied under the harsh terms of the 1940 armistice with Nazi Germany, it adopted a policy of collaboration. Though Paris was nominally its capital, the government established itself in the resort town of Vichy in the unoccupied "free zone" (zone libre), where it remained responsible for the civil administration of France as well as its colonies.[3] The occupation of France by Nazi Germany at first affected only the northern and western portions of the country, but in November 1942 the Germans and Italians occupied the remainder of Metropolitan France, ending any pretence of independence by the Vichy government.

The

At Vichy, Pétain established an authoritarian government that reversed many liberal policies and began tight supervision of the economy. Conservative Catholics became prominent, and Paris lost its avant-garde status in European art and culture. The media were tightly controlled and promoted antisemitism and, after Operation Barbarossa started in June 1941, anti-Sovietism. The terms of the armistice allowed some degree of independence and neutrality to the Vichy government, such as keeping the French Navy and French colonial empire under French control and avoiding full occupation of the country by Germany. Despite heavy pressure, the Vichy government never joined the Axis powers and even remained formally at war with Germany. In practice, Vichy France became a collaborationist regime.

Germany kept

Most of the French public initially supported the regime, but opinion turned against the Vichy government and the occupying German forces as the war dragged on and living conditions in France worsened. Open opposition intensified as it became clear that Germany was losing the war. The French Resistance, working largely in concert with the London-based Free France movement, increased in strength over the course of the occupation. After the liberation of France began in 1944, the Free French Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF) was installed as the new national government, led by Charles de Gaulle.

The last of the Vichy exiles were captured in the Sigmaringen enclave in April 1945. Pétain was put on trial for treason by the new Provisional Government, and sentenced to death, but this was commuted to life imprisonment by de Gaulle. Only four senior Vichy officials were tried for crimes against humanity, although many had participated in the deportation of Jews, abuses of prisoners, and severe acts against members of the Resistance.

Overview

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2013) |

In 1940, Marshal

Terminology

After the

The territory under the control of the French State was based in the city of Vichy, in the unoccupied southern portion of Metropolitan France. This was south of the

Jurisdiction

In theory, the civil jurisdiction of the Vichy government extended over most of

The Nazis had some intention of annexing a large swath of northeastern France, replacing that region's inhabitants with German settlers, and initially forbade French refugees from returning to the region, but the restrictions were never thoroughly enforced and were basically abandoned following the invasion of the Soviet Union, which had the effect of turning German territorial ambitions almost exclusively to the East. German troops guarding the boundary line of the northeastern Zone interdite were withdrawn on the night of 17–18 December 1941, but the line remained in place on paper for the remainder of the occupation.[8]

Nevertheless, effectively Alsace-Lorraine was annexed: German law applied to the region, its inhabitants were conscripted into the Wehrmacht[9] and pointedly the customs posts separating France from Germany were placed back where they had been between 1871 and 1918. Similarly, a sliver of French territory in the Alps was under direct Italian administration from June 1940 to September 1943. Throughout the rest of the country, civil servants were under the formal authority of French ministers in Vichy.[citation needed] René Bousquet, the head of French police nominated by Vichy, exercised his power in Paris through his second-in-command, Jean Leguay, who coordinated raids with the Nazis. German laws took precedence over French laws in the occupied territories, and the Germans often rode roughshod over the sensibilities of Vichy administrators.

On 11 November 1942, following the landing of the Allies in North Africa (Operation Torch), the Axis launched Operation Anton, occupying southern France and disbanding the strictly limited "Armistice Army" that Vichy had been allowed by the armistice.

Legitimacy

Vichy's claim to be the legitimate French government was denied by Free France and by all subsequent French governments

Ideology

The Vichy regime sought an anti-modern

The Vichy government tried to assert its legitimacy by symbolically connecting itself with the

To advance his message, Pétain frequently spoke on French radio. In his radio speeches, Pétain always used the personal pronoun je (French for the English word "I"), portrayed himself as a Christ-like figure sacrificing himself for France and assuming a God-like tone of a semi-omniscient narrator who knew truths about the world that the rest of the French did not.[23] To justify the Vichy ideology of the Révolution nationale ("national revolution"), Pétain needed a radical break with the French Third Republic. During his radio speeches, the entire French Third Republic era was always painted in the blackest of colours as a time of décadence ("decadence") when the French people were alleged to have suffered moral degeneration and decline.[24]

Summarising Pétain's speeches, the British historian Christopher Flood wrote that Pétain blamed la décadence on "political and economic liberalism, with its divisive,

The key component of Vichy's ideology was

No other nation was attacked as frequently and violently as Britain was in Vichy propaganda.

Fall of France and establishment of the Vichy government

France declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939 after the

While the debate continued, the government was forced to relocate several times to avoid capture by advancing German forces and finally reached Bordeaux. Communications were poor and thousands of civilian refugees clogged the roads. In those chaotic conditions, advocates of an armistice gained the upper hand. The Cabinet agreed on a proposal to seek armistice terms from Germany with the understanding that if Germany set forth dishonourable or excessively-harsh terms, France would retain the option to continue to fight. General Charles Huntziger, who headed the French armistice delegation, was told to break off negotiations if the Germans demanded the occupation of all of Metropolitan France, the French fleet, or any of the French overseas territories. The Germans did not, however, make any of those demands.[45]

Prime Minister Reynaud favoured continuing the war but was soon outvoted by those who advocated an armistice. Facing an untenable situation, Reynaud resigned and, on his recommendation, President

Adolf Hitler had a number of reasons for agreeing to an armistice. He wanted to ensure that France did not continue to fight from North Africa and that the French Navy was taken out of the war. In addition, leaving a French government in place would relieve Germany of the considerable burden of administering French territory, particularly as Hitler turned his attention toward Britain, which did not surrender and fought on against Germany. Finally, as Germany lacked a navy sufficient to occupy France's overseas territories, Hitler's only practical recourse to deny the British the use of those territories was to maintain France's status as a de jure independent and neutral nation and to send a message to Britain that it was alone, with France appearing to switch sides and the United States remaining neutral. However, German espionage against France after its defeat intensified greatly, particularly in southern France.[46]

Conditions of armistice

As per the terms of the Franco-German armistice of June 22, 1940, Nazi Germany effectively annexed the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine while the German army occupied northern metropolitan France and all the Atlantic coastline down to the border with Spain.[47] That left the rest of France, including the remaining two-fifths of southern and eastern metropolitan France and Overseas France North Africa, unoccupied, and under the control of a collaborationist French government based at the city of Vichy, and headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Ostensibly, the Vichy French government administered the whole of France (excluding Alsace-Lorraine), including Overseas Vichy France-North Africa.

Prisoners

Germany took two million French soldiers as prisoners-of-war and sent them to camps in Germany. About a third had been released on various terms by 1944. Of the remainder, the officers and NCOs (corporals and sergeants) were kept in camps but were exempt from forced labour. The privates were first sent to "Stalag" camps for processing and were then put to work. About half of them worked in German agriculture, where food rations were adequate and controls were lenient. The others worked in factories or mines, where conditions were much harsher.[48]

Armistice Army

The Germans occupied northern France directly. The French had to pay costs for the 300,000-strong German occupation army, amounting to 20 million Reichsmarks per day, at the artificial rate of twenty Francs to the Reichsmark[citation needed]. That was 50 times the actual costs of the occupation garrison[citation needed]. The French government also had responsibility for preventing French citizens from escaping into exile.

Article IV of the Armistice allowed for a small French army – the Armistice Army (Armée de l'Armistice) – stationed in the unoccupied zone, and for the military provision of the French colonial empire overseas. The function of those forces was to keep internal order and to defend French territories from Allied assault. The French forces were to remain under the overall direction of the German armed forces.

The exact strength of the Vichy French Metropolitan Army was set at 3,768 officers, 15,072 non-commissioned officers, and 75,360 men. All members had to be volunteers. In addition to the army, the size of the Gendarmerie was fixed at 60,000 men plus an anti-aircraft force of 10,000 men. Despite the influx of trained soldiers from the colonial forces (reduced in size in accordance with the armistice), there was a shortage of volunteers. As a result, 30,000 men of the class of 1939 were retained to fill the quota. In early 1942 those conscripts were released, but there were still not enough men. That shortage remained until the regime's dissolution, despite Vichy appeals to the Germans for a regular form of conscription.

The Vichy French Metropolitan Army was deprived of tanks and other armoured vehicles and was desperately short of motorised transport, a particular problem for cavalry units. Surviving recruiting posters stress the opportunities for athletic activities, including horsemanship, reflecting both the general emphasis placed by the Vichy government on rural virtues and outdoor activities and the realities of service in a small and technologically backward military force. Traditional features characteristic of the pre-1940 French Army, such as kepis and heavy capotes (buttoned-back greatcoats) were replaced by berets and simplified uniforms.

The Vichy authorities did not deploy the Army of the Armistice against resistance groups active in the south of France, reserving that role to the Vichy Milice (militia), a paramilitary force created on 30 January 1943 by the Vichy government to combat the Resistance.[50] Members of the regular army could thus defect to the Maquis after the German occupation of southern France and the disbandment of the Army of the Armistice in November 1942. By contrast, the Milice continued to collaborate, and its members were subject to reprisals after the Liberation.

Vichy French colonial forces were reduced in accordance with the terms of the armistice, but in the Mediterranean area alone, Vichy still had nearly 150,000 men under arms. There were about 55,000 in

German custody

The Armistice required France to turn over any German citizens within the country upon German demand. The French regarded this as a "dishonorable" term since it would require France to hand over persons who had entered France seeking refuge from Germany. Attempts to negotiate the point with Germany proved unsuccessful, and the French decided not to press the issue to the point of refusing the Armistice.

10 July 1940 vote of full powers

On 10 July 1940, the

Most legislators believed that democracy would continue, albeit with a new constitution. Although Laval said on 6 July that "parliamentary democracy has lost the war; it must disappear, ceding its place to an authoritarian, hierarchical, national and social regime", the majority trusted Pétain. Léon Blum, who voted no, wrote three months later that Laval's "obvious objective was to cut all the roots that bound France to its republican and revolutionary past. His 'national revolution' was to be a counter-revolution eliminating all the progress and human rights won in the last one hundred and fifty years".

The majority of

- Abrogation of legal procedure

- The impossibility for Parliament to delegate its constitutional powers without controlling their use a posteriori.

- The 1884 constitutional amendment making it unconstitutional to put into question the "republican form" of the government.

Out of a total of 544 Deputies, only 414 voted; and out of a total of 302 senators, only 235 voted. Of these, 357 deputies voted in favour of Pétain and 57 against, while 212 senators voted for Pétain, and 23 against. Thus, Pétain was approved by 65% of all deputies and 70% of all senators. Although Pétain could claim legality for himself, particularly in comparison with the essentially self-appointed leadership of Charles de Gaulle, the dubious circumstances of the vote explain why most French historians do not consider Vichy a complete continuity of the French state.[56]

The text voted by the Congress stated:

The National Assembly gives full powers to the government of the Republic, under the authority and the signature of Marshal Pétain, to the effect of promulgating by one or several acts a new constitution of the French state. This constitution must guarantee the rights of labour, of family and of the homeland. It will be ratified by the nation and applied by the assemblies which it has created.[57]

The Constitutional Acts of 11 and 12 July 1940

Pétain was a reactionary by nature and education, despite his status as a hero of the Third Republic during World War I. Almost as soon as he was granted full powers, Pétain began blaming the Third Republic's democracy and endemic corruption for France's humiliating defeat by Germany. Accordingly, his government soon began taking on authoritarian characteristics. Democratic liberties and guarantees were immediately suspended.

Governments

There were five governments during the tenure of the Vichy regime, starting with the continuation of Pétain's position from the Third Republic, which dissolved itself and handed him full powers, leaving Pétain in absolute control of the new, "French State" as Pétain named it. Pierre Laval formed the first government in 1940. The second government was formed by Pierre-Étienne Flandin, and lasted just two months until February 1941. François Darlan was then head of government until April 1942, followed by Pierre Laval again until August 1944. The Vichy government fled into exile in Sigmaringen in September 1944.

Foreign relations

Vichy France in 1940–1942 was recognised by most

The US position towards Vichy France and de Gaulle was especially hesitant and inconsistent. Roosevelt disliked de Gaulle and regarded him as an "apprentice dictator".[64] The Americans first tried to support General Maxime Weygand, general delegate of Vichy for Africa until December 1941. After the first choice had failed, they turned to Henri Giraud shortly before the landing in North Africa on 8 November 1942. Finally, after Admiral François Darlan's turn towards the Free Forces (he had been prime minister from February 1941 to April 1942) they played him against de Gaulle.[64]

US General

Moscow maintained full diplomatic relations with the Vichy government until 30 June 1941, when they were broken by Vichy expressing support for Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. In response to British requests and sensitivities of the French-Canadian population, Canada, despite being at war with the Axis since 1939, maintained full diplomatic relations with the Vichy regime until early November 1942, when Case Anton led to the complete occupation of Vichy France by the Germans.[65]

The British feared that the French naval fleet could end up in German hands and be used against its own naval forces, which were so vital to maintaining North Atlantic shipping and communications. Under the armistice, France had been allowed to retain the

Switzerland and other neutral states maintained diplomatic relations with the Vichy regime until the liberation of France in 1944, when Pétain resigned and was deported to Germany for the creation of a forced government-in-exile.[67]

French Indochina, Japan and Franco-Thai War

In June 1940, the

Colonial struggle with Free France

To counter the Vichy government, General Charles de Gaulle created the

India and Oceania

Until 1962, France possessed

Following the

In the

In Wallis and Futuna, the local administrator and bishop sided with Vichy but faced opposition from some of the population and clergy; their attempts at naming a local king in 1941 to buffer the territory from their opponents backfired as the newly elected king refused to declare allegiance to Pétain. The situation stagnated for a long while due to the remoteness of the islands and because no overseas ship visited the islands for 17 months after January 1941. An aviso sent from Nouméa took over Wallis on behalf of the Free French on 27 May 1942 and Futuna on 29 May 1942. That allowed American forces to build an airbase and seaplane base on Wallis (Navy 207) that served the Allied Pacific operations.[78]

Americas

A Vichy France plan to have Western Union build powerful transmitters on Saint Pierre and Miquelon in 1941 to enable private trans-Atlantic communications was blocked after pressure by Roosevelt. On 24 December 1941 Free French forces on three corvettes, supported by a submarine landed and seized control of Saint Pierre and Miquelon on orders from Charles de Gaulle without reference to any of the Allied commanders.[79]

French Guiana, on the northern coast of South America, removed its Vichy-supporting government on 22 March 1943,[80] shortly after eight allied ships had been sunk by a German submarine off the coast of Guiana,[81] and the arrival of American troops by air on 20 March.[80]

Martinique became home to the bulk of the Gold reserve of the Bank of France, with 286 tons of gold transported there on the French cruiser Émile Bertin in June 1940. The island was blockaded by the British navy until an agreement was reached to immobilise French ships in port. The British used the gold as collateral for Lend-Lease facilities from the Americans on the basis that it could be "acquired" at any time if needed.[79] In July 1943, Free French sympathisers on the island took control of the gold and the fleet once Admiral Georges Robert departed following a threat by America to launch a full-scale invasion.[80]

Guadeloupe, in the French West Indies, also changed allegiance in 1943 after Admiral Georges Robert ordered police to fire on protestors,[82] before he fled back to Europe.

Equatorial and West Africa

In Central Africa, three of the four colonies in

On 23 September 1940, the

One colony in French Equatorial Africa, Gabon, had to be occupied by military force between 27 October and 12 November 1940.[83] On 8 November 1940, Free French forces under the command of de Gaulle and Marie-Pierre Kœnig, along with the assistance of the Royal Navy, invaded Vichy-held Gabon. The capital, Libreville, was bombed and captured. The final Vichy troops in Gabon surrendered without any military confrontation with the Allies at Port-Gentil.

French Somaliland

The governor of French Somaliland (now

In March 1941, the British enforcement of a strict contraband regime to prevent supplies being passed on to the Italians, lost its point after the conquest of

Wavell considered that if British pressure was applied, a rally would appear to have been coerced. Wavell preferred to let the propaganda continue and provided a small amount of supplies under strict control. When the policy had no effect, Wavell suggested negotiations with Vichy governor Louis Nouailhetas to use the port and railway. The suggestion was accepted by the British government but because of the concessions granted to the Vichy regime in Syria, proposals were made to invade the colony instead. In June, Nouailhetas was given an ultimatum, the blockade was tightened and the Italian garrison at Assab was defeated by an operation from Aden. For six months, Nouailhetas remained willing to grant concessions over the port and railway but would not tolerate Free French interference. In October, the blockade was reviewed, but the beginning of the war against Japan in December led to all but two blockade ships being withdrawn. On 2 January 1942, the Vichy government offered the use of the port and railway, subject to the lifting of the blockade but the British refused and ended the blockade unilaterally in March.[88]

Syria and Madagascar

The next flashpoint between Britain and Vichy France came when a

The additional participation of Free French forces in the Syrian operation was controversial within Allied circles. It raised the prospect of Frenchmen shooting at Frenchmen, raising fears of a civil war. Additionally it was believed that the Free French were widely reviled within Vichy military circles and that Vichy forces in Syria were less likely to resist the British if they were not accompanied by elements of the Free French. Nevertheless, de Gaulle convinced Churchill to allow his forces to participate, although de Gaulle was forced to agree to a joint British and Free French proclamation promising that Syria and Lebanon would become fully independent at the end of the war.

From 5 May to 6 November 1942, British and Commonwealth forces conducted Operation Ironclad, known as the Battle of Madagascar, the seizure of the large, Vichy French-controlled island of Madagascar, which the British feared Japanese forces might use as a base to disrupt trade and communications in the Indian Ocean. The initial landing at Diégo-Suarez was relatively quick, though it took British forces a further six months to gain control of the entire island.[citation needed]

French North Africa

Operation Torch was the American and British invasion of French North Africa (

In North Africa, after the 8 November 1942

Henri Giraud arrived in Algiers on 10 November 1942 and agreed to subordinate himself to Admiral Darlan as the French Africa army commander. Even though Darlan was now in the Allied camp, he maintained the repressive Vichy system in North Africa, including

After Darlan's assassination, Henri Giraud became his de facto successor in French Africa with Allied support. That occurred through a series of consultations between Giraud and de Gaulle. The latter wanted to pursue a political position in France and agreed to have Giraud as commander-in-chief, who was more qualified militarily. Later, the Americans sent

Giraud took part in the

In late April 1945

Collaboration with Nazi Germany

Vichy is often described as a German puppet state, although it has also been argued it had an agenda of its own.[92][93]

Historians distinguish between state collaboration followed by the Vichy regime, and "collaborationists", who were private French citizens eager to collaborate with Germany and who pushed towards a radicalisation of the regime. Pétainistes, on the other hand, were direct supporters of Marshal Pétain rather than of Germany (although they accepted Pétain's state collaboration). State collaboration was sealed by the

The composition and policies of the Vichy cabinet were mixed. Many Vichy officials, such as Pétain, were

On the other hand,

The reorganisation and unification of the French police by

Racial policies and collaboration

Germany interfered little in internal French affairs for the first two years after the armistice, as long as public order was maintained.

In July 1940, Vichy set up a special commission charged with reviewing

The

The Third Republic had first opened concentration camps during World War I for the internment of

Suspicions had been raised amongst prefects and police officials by the Vichy Minister of Interior as to the intentions of the men working within the camps. Many were suspected of retaining ties to anti-fascist groups as well as the burgeoning maquis and resistance groups, in particular in the southern departments. The Vichy Minister of Interior wrote in 1942; "I am advised that the Travailleurs Étrangers...continue to be mobilization centres on behalf of the revolution. The responsible leaders of the communist activities have been recruiting among the Spanish Republicans...who, during the civil war in their own country, showed that they are capable of furnishing the core of an insurrectionary army".[104]

Besides the political prisoners already detained there, Gurs was then used to intern foreign Jews,

Besides the concentration camps opened by Vichy, the Germans also opened some

The Vichy government took a number of racially motivated measures. In August 1940, laws against antisemitism in the media (the

Vichy also enacted racial laws in its territories in North Africa. "The history of the Holocaust in France's three North African colonies (Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia) is intrinsically tied to France's fate during this period."[109][110][111][112][113]

With regard to economic contribution to the German economy, it is estimated that France provided 42% of the total foreign aid.[114]

Eugenics policies

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

In 1941, Nobel Prize winner Alexis Carrel, an early proponent of eugenics and euthanasia, and a member of Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party (PPF),[citation needed] advocated for the creation of the French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems (Fondation Française pour l'Étude des Problèmes Humains), using connections to the Pétain cabinet. Charged with the "study, in all of its aspects, of measures aimed at safeguarding, improving and developing the French population in all of its activities", the Foundation was created by decree of the collaborationist Vichy regime in 1941, and Carrel was appointed as "regent".[115] The Foundation also had for some time as general secretary François Perroux.[citation needed]

The Foundation was behind the 16 December 1942 Act mandating the "

The Foundation initiated studies on demographics (Robert Gessain, Paul Vincent, Jean Bourgeois), nutrition (Jean Sutter), and housing (Jean Merlet), as well as the first polls (

Alexis Carrel had previously published in 1935 the best-selling book L'Homme, cet inconnu ("Man, This Unknown"). Since the early 1930s, Carrel had advocated the use of

The German government has taken energetic measures against the propagation of the defective, the mentally diseased, and the criminal. The ideal solution would be the suppression of each of these individuals as soon as he has proven himself to be dangerous.[118]

Carrel also wrote this in his book:

The conditioning of petty criminals with the whip, or some more scientific procedure, followed by a short stay in hospital, would probably suffice to ensure order. Those who have murdered, robbed while armed with automatic pistol or machine gun, kidnapped children, despoiled the poor of their savings, misled the public in important matters, should be humanely and economically disposed of in small euthanasic institutions supplied with proper gasses. A similar treatment could be advantageously applied to the insane, guilty of criminal acts.[119]

Alexis Carrel had also taken an active part to a symposium in Pontigny organised by Jean Coutrot, the "Entretiens de Pontigny".[citation needed] Scholars such as Lucien Bonnafé, Patrick Tort, and Max Lafont have accused Carrel of responsibility for the execution of thousands of mentally ill or impaired patients under Vichy.[116]

Antisemitic laws

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

A Nazi ordinance dated 21 September 1940 forced Jews of the occupied zone to declare themselves as such at a police station or

On 3 October 1940, the Vichy government promulgated the

The police oversaw the confiscation of telephones and radios from Jewish homes and enforced a curfew on Jews starting in February 1942. They also enforced requirements that Jews not appear in public places and ride only on the last car of the Parisian metro.

Along with many French police officials, André Tulard was present on the day of the inauguration of Drancy internment camp in 1941[

July 1942 Vel' d'Hiv Roundup

In July 1942, under German orders, the French police organised the

August 1942 and January 1943 raids

The French police, headed by Bousquet, arrested 7,000 Jews in the southern zone in August 1942. 2,500 of them transited through the

Jewish death toll

In 1940, approximately 350,000 Jews lived in

Proportionally, either number makes for a lower death toll than in some other countries (in the Netherlands, 75% of the Jewish population was murdered).[128] This fact has been used as arguments by supporters of Vichy; according to Paxton, the figure would have been greatly lower if the "French state" had not willfully collaborated with Germany, which lacked staff for police activities. During the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup of July 1942, Laval ordered the deportation of children, against explicit German orders. Paxton pointed out that if the total number of victims had not been higher, it was due to the shortage in wagons, the resistance of the civilian population, and deportation in other countries (notably in Italy).[128]

Government responsibility

For decades, the French government argued that the

The first official admission that the French State had been complicit in the deportation of 76,000 Jews during WW II was made in 1995 by then President Jacques Chirac, at the site of the Vélodrome d'Hiver, where 13,000 Jews had been rounded up for deportation to death camps in July 1942. "France, on that day [16 July 1942], committed the irreparable. Breaking its word, it handed those who were under its protection over to their executioners," he said. Those responsible for the roundup were "450 policemen and gendarmes, French, under the authority of their leaders [who] obeyed the demands of the Nazis..... the criminal folly of the occupiers was seconded by the French, by the French state".[133][134][135]

On 16 July 2017, also at a ceremony at the Vel' d'Hiv site, President Emmanuel Macron denounced the country's role in the Holocaust in France and the historical revisionism that denied France's responsibility for the 1942 roundup and subsequent deportation of 13,000 Jews. "It was indeed France that organised this," Macron insisted, French police collaborating with the Nazis. "Not a single German" was directly involved," he added. Macron was even more specific than Chirac had been in stating that the Government during the War was certainly that of France. "It is convenient to see the Vichy regime as born of nothingness, returned to nothingness. Yes, it's convenient, but it is false. We cannot build pride upon a lie."[136][137]

Macron made a subtle reference to Chirac's remark when he added, "I say it again here. It was indeed France that organized the roundup, the deportation, and thus, for almost all, death."[138][139]

Collaborationnistes

Collaborationnisme (English: collaborationism) should be distinguished from collaboration. Collaborationism refers to those, primarily from the fascist right, who embraced the goal of a German victory as their own,[141][142] whereas collaboration refers to those of the French who for whatever reason collaborated with the Germans. Organizations such as La Cagoule opposed the Third Republic, particularly while the left-wing Popular Front was in power.[citation needed]

Collaborationists may have influenced the Vichy government's policies, but ultra-collaborationists never comprised the majority of the government before 1944.[143]

To enforce the régime's will, some paramilitary organisations were created. One example was the

Social and economic history

Vichy authorities strongly opposed "modern" social trends and tried "national regeneration" to restore behaviour more in line with traditional Catholicism. Philip Manow argued that, "Vichy represents the authoritarian, antidemocratic solution that the French political right, in coalition with the national Church hierarchy, had sought repeatedly during the interwar period and almost put in place in 1934".[144] Calling for "National Regeneration", Vichy reversed many liberal policies and began tight supervision of the economy, with central planning as a key feature.[18]

Labour unions came under tight government control. There were no elections. The independence of women was reversed, with an emphasis put on motherhood. Government agencies had to fire married women employees.[citation needed] Conservative Catholics became prominent. Paris lost its avant-garde status in European art and culture.[145] The media were tightly controlled and stressed virulent anti-Semitism and, after June 1941, anti-Bolshevism.[18] Hans Petter Graver wrote that Vichy "is notorious for its enactment of anti-Semitic laws and decrees, and these were all loyally enforced by the judiciary".[146]

Economy

Vichy rhetoric exalted the skilled labourer and small businessman. In practice, the needs of artisans for raw materials were neglected in favour of big businesses.[147] The General Committee for the Organization of Commerce (CGOC) was a national program to modernise and professionalise small business.[148] In 1941 it also instituted the mobilization of non-ferrous metals under the cover of supporting French agriculture but in fact to support flagging German armament production.

In 1940, the government took direct control of all production, which was synchronised with German demands. It replaced free trade unions with compulsory state unions that dictated labour policy without regard to the voice or needs of the workers. The centralised bureaucratic control of the French economy was not a success, as German demands grew heavier and more unrealistic, passive resistance and inefficiencies multiplied and Allied bombers hit the rail yards. Vichy made the first comprehensive long-range plans for the French economy, but the government had never attempted a comprehensive overview. De Gaulle's provisional government in 1944–45 quietly used the Vichy plans as a base for its own reconstruction program. The Monnet Plan of 1946 reaped the heritage of previous efforts at planning in the 1930s, Vichy, the Resistance, and the Provisional Government.[149] Monnet's plan to modernize the economy was designed to improve the country's competitive position so as to prepare it for participation in an open multilateral system and, thereby, to reduce the need for trade protection.[150]

Forced labour

Nazi Germany kept French prisoners-of-war as forced labourers throughout the war. They added compulsory and volunteer workers from occupied nations, especially in metal factories. The shortage of volunteers led the Vichy government to pass a law in September 1942 that effectively deported workers to Germany, where they were 15% of the labour force by August 1944. The largest number worked in the giant Krupp steel works in Essen. Low pay, long hours, frequent bombings and crowded air raid shelters added to the unpleasant conditions of poor housing, inadequate heating, limited food, and poor medical care, all compounded by harsh Nazi discipline. The workers finally returned home in the summer of 1945.[151] The forced labour draft encouraged the French Resistance and undermined the Vichy government.[152]

Food shortages

Civilians suffered shortages of all varieties of consumer goods.[153] The rationing system was stringent and badly mismanaged, leading to malnourishment, black markets and hostility to state management of the food supply. The Germans seized about 20% of the French food production, causing severe disruption to the French household economy.[154] French farm production fell by half because of lack of fuel, fertiliser and workers. Even so, the Germans seized half the meat, 20% of the produce and 2% of the champagne.[155] Supply problems quickly affected French stores, which lacked most items. The government answered by rationing, but German officials set the policies, and hunger prevailed, especially affecting youth in urban areas. The queues lengthened in front of shops.

Some people, including German soldiers, benefited from the black market, where food was sold without tickets at very high prices. Farmers especially diverted meat to the black market and so there was much less for the open market. Counterfeit food tickets were also in circulation. Direct buying from farmers in the countryside and barter against cigarettes became common although those activities were strictly forbidden and thus carried the risk of confiscation and fines.

Food shortages were most acute in the large cities. In the more remote country villages, clandestine slaughtering, vegetable gardens and the availability of milk products permitted better survival. The official ration provided starvation level diets of 1013 or fewer calories a day, supplemented by home gardens and especially black market purchases.[156]

Women

The two million French soldiers held as prisoners-of-war and forced labourers in Germany throughout the war were not at risk of death in combat, but the anxieties of separation for their 800,000 wives were high. The government provided a modest allowance, but one in ten became prostitutes to support their families.[157]

Meanwhile, the Vichy regime promoted a highly-traditional model of female roles.[158] The National Revolution's official ideology fostered the patriarchal family, headed by a man with a subservient wife, who was devoted to her many children. It gave women a key symbolic role to carry out the national regeneration and used propaganda, women's organisations and legislation to promote maternity; patriotic duty and female submission to marriage, home and children's education.[153] The falling birth rate appeared to be a grave problem to Vichy, which introduced family allowances and opposed birth control and abortion. Conditions were very difficult for housewives, as food was short as well as most necessities.[159] Mother's Day became a major date in the Vichy calendar, with festivities in the towns and schools featuring the award of medals to mothers of numerous children. Divorce laws were made much more stringent, and restrictions were placed on the employment of married women. Family allowances, which had begun in the 1930s, were continued and became a vital lifeline for many families as a monthly cash bonus for having more children. In 1942, the birth rate started to rise, and by 1945, it was higher than it had been for a century.[160]

On the other side, women of the Resistance, many of whom were associated with combat groups linked to the French Communist Party, broke the gender barrier by fighting side by side with men. After the war, this was considered to have been a mistake, but France did give women the vote in 1944.[161]

German invasion, November 1942

Hitler ordered Case Anton to occupy Corsica and then the rest of the unoccupied southern zone in immediate reaction to the landing of the Allies in North Africa (Operation Torch) on 8 November 1942. Following the conclusion of the operation on 12 November, Vichy's remaining military forces were disbanded. Vichy continued to exercise its remaining jurisdiction over almost all of metropolitan France, with the residual power devolved into the hands of Laval, until the gradual collapse of the regime following the Allied invasion in June 1944. On 7 September 1944, following the Allied invasion of France, the remainders of the Vichy government cabinet fled to Germany and established a puppet government in exile in the so-called Sigmaringen enclave. That rump government finally fell when the city was taken by the Allied French army in April 1945.

Part of the residual legitimacy of the Vichy regime resulted from the continued ambivalence of U.S. and other leaders. President Roosevelt continued to cultivate Vichy, and promoted General

Following the invasion of France via Normandy and Provence (

Decline of the regime

Independence of the SOL

In 1943 the

Sigmaringen commission

Following the liberation of Paris on 25 August 1944, Pétain and his ministers were taken to Sigmaringen by the German forces. After both Pétain and Laval refused to cooperate, Fernand de Brinon was selected by the Germans to establish a pseudo-government in exile at Sigmaringen. Pétain refused to participate further and the Sigmaringen operation had little to no authority. The offices used the official title "French Government Commission for the Defense of National Interests" (French: Commission gouvernementale française pour la défense des intérêts nationaux) and informally was known as the "French Delegation" (French: Délégation française). The enclave had its own radio station (Radio-patrie, Ici la France) and official press (La France, Le Petit Parisien), and hosted the embassies of Axis powers Germany and Japan, as well as an Italian consulate. The population of the enclave was about 6,000, including known collaborationist journalists, the writers Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Lucien Rebatet, the actor Robert Le Vigan, and their families, as well as 500 soldiers, 700 French SS, prisoners of war and French civilian forced labourers.[162]

The Commission lasted for seven months, surviving Allied bombing runs, poor nutrition and housing, and a bitterly cold winter where temperatures plunged to −30 °C (−22 °F), while residents nervously watched the advancing Allied troops drawing closer and discussed rumors.[163]

On 21 April 1945

Aftermath

Provisional government

The Free French, concerned that the Allies might decide to put France under administration of the

The provisional government considered the Vichy government to have been unconstitutional and all of its actions therefore without legitimate authority. All "constitutional acts, legislative or regulatory" taken by the Vichy government, as well as decrees taken to implement them, were declared null and void by the

Collaborationist paramilitary and political organisations, such as the Milice and the Service d'ordre légionnaire, were also dissolved.[167]

The Provisional Government also took steps to replace local governments, including governments that had been suppressed by the Vichy regime through new elections or by extending the terms of those who had been elected not later than 1939.[168]

Purges

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2016) |

After the liberation, France was swept for a short period with a wave of executions of collaborationists. Some were brought to the

Four different periods are distinguished by historians:

- the first phase of popular convictions (épuration sauvage – wild purge): extrajudicial executions and shaving of women's heads. Estimations by police prefectsmade in 1948 and 1952 counted as many as 6,000 executions before the Liberation and 4,000 afterward.

- the second phase (épuration légale or legal purge), which began with Charles de Gaulle's 26 and 27 June 1944 purge ordonnances (de Gaulle's first ordonnance instituting purge Commissions was enacted on 18 August 1943): judgments of collaborationists by the Commissions d'épuration, who condemned approximately 120,000 persons (e.g. Charles Maurras, the leader of the royalist Action Française, was thus condemned to a life sentence on 25 January 1945), including 1,500 death sentences (Joseph Darnand, head of the Milice, and Pierre Laval, head of the French government, were executed after trial on 4 October 1945, Robert Brasillach, executed on 6 February 1945, etc.), but many of those who survived that phase were later given amnesty.

- the third phase, more lenient towards collaborationists (the trial of Philippe Pétain or of writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline).

- finally came the period for amnesty and graces (such as Jean-Pierre Esteva, Xavier Vallat, creator of the General Commission for Jewish Affairs, René Bousquet, head of French police)

Other historians have distinguished the purges against intellectuals (Brasillach, Céline, etc.), industrialists, fighters (LVF etc.) and civil servants (Papon etc.).

Philippe Pétain was charged with treason in July 1945. He was convicted and sentenced to death by firing squad, but Charles de Gaulle commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. In the police, some collaborators soon resumed official responsibilities. This continuity of the administration was pointed out,[citation needed] in particular concerning the events of the Paris massacre of 1961, executed under the orders of Paris Police Chief Maurice Papon while Charles de Gaulle was head of state. Papon was tried and convicted for crimes against humanity in 1998.

The French members of the Waffen-SS

Among artists, singer

Executions without trials and other forms of "popular justice" were harshly criticised immediately after the war, with circles close to Pétainists advancing the figures of 100,000 and denouncing the "Red Terror", "anarchy", or "blind vengeance". The writer and Jewish internee Robert Aron estimated the popular executions to a number of 40,000 in 1960. This surprised de Gaulle, who estimated the number to be around 10,000, which is also the figure accepted today by mainstream historians. Approximately 9,000 of these 10,000 refer to summary executions in the whole of the country, which occurred during battle.[citation needed]

Some imply that France did too little to deal with collaborators at this stage by selectively pointing out that in absolute value (numbers), there were fewer legal executions in France than in its smaller neighbour Belgium, and fewer internments than in Norway or the Netherlands[citation needed], but the situation in Belgium was not comparable as it mixed collaboration with elements of a war of secession. The 1940 invasion prompted the Flemish population to generally side with the Germans in the hope of gaining national recognition, and relative to national population, a much higher proportion of Belgians than French thus ended up collaborating with the Germans or volunteering to fight alongside them.[169][170] The Walloon population, in turn, led massive anti-Flemish retribution after the war, some of which, such as the execution of Irma Swertvaeger Laplasse, were controversial.[171]

The proportion of collaborators was also higher in Norway, and collaboration occurred on a larger scale in the Netherlands (as in Flanders), based partly on linguistic and cultural commonality with Germany. The internments in Norway and the Netherlands, meanwhile, were highly temporary and rather indiscriminate: there was a brief internment peak in these countries since internment was used partly for the purpose of separating collaborationists from others.[172] Norway ended up executing only 37 collaborationists.

1980s trials

Some accused war criminals were judged, some for a second time, from the 1980s onwards:

In 1993, former Vichy official René Bousquet was assassinated while he awaited prosecution in Paris following a 1991 inculpation for crimes against humanity. He had been prosecuted but partially acquitted and immediately amnestied in 1949.[174] In 1994, former Vichy official Paul Touvier (1915–1996) was convicted of crimes against humanity. Maurice Papon was likewise convicted in 1998 but was released three years later due to ill health and died in 2007.[175]

Historiographical debates and "Vichy syndrome"

As the historian Henry Rousso put it in The Vichy Syndrome (1987), Vichy and the state collaboration of France remains a "past that doesn't pass away".[176]

Historiographical debates are still passionate and oppose different views on the nature and legitimacy of Vichy's collaborationism with Germany in the implementation of the Holocaust. Three main periods have been distinguished in the historiography of Vichy. Firstly, the Gaullist period aimed at national reconciliation and unity under the figure of Charles de Gaulle, who conceived himself above political parties and divisions. Then, the 1960s had

Though it is certain that the Vichy government and many of its top administration collaborated in the implementation of the Holocaust, the exact level of such co-operation is still debated. Compared with the Jewish communities established in other countries invaded by Germany, French Jews suffered proportionately lighter losses (see Jewish death toll section above), but in 1942, repression and deportations started to strike French Jews, not just foreign Jews.[108]

Notable figures

- René Bousquet, head of the French police.

- François Darlan, Prime Minister (1941–1942).

- Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, Commissioner for Jewish Affairs.

- Rassemblement national populaire(RNP) in 1941. Joined the government in the last months of the Occupation.

- Pierre-Étienne Flandin, Prime Minister (1940–1941).

- Philippe Henriot, State Secretary of Information and Propaganda.

- Gaston Henry-Haye, Vichy ambassador to the United States of America.

- Charles Huntziger, general and Minister of Defense.

- Pierre Laval, Prime Minister (1940, 1942–1944).

- Jean Leguay, delegate of Bousquet in the "free zone", charged with crimes against humanity for his role in the July 1942 Vel' d'Hiv Roundup.

- François Mitterrand, later President of the French Republic (1981–1995)

- Maurice Papon, head of the Jewish Questions Service in the prefecture of Bordeaux. Condemned for crimes against humanity in 1998.[178]

- Philippe Pétain, Head of State.

- Pierre Pucheu, Minister of the Interior.

- Parti Populaire Françaisin Marseille.

- Paul Touvier, condemned in 1995 for crimes against humanity for his role as head of the Milice in Lyon.

- Xavier Vallat, Commissioner General for Jewish Questions.

- Maxime Weygand, Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces and Minister of Defense.

Non-Vichy collaborationists

- Pierre Bonny, also known as Pierre Bony.

- Robert Brasillach, writer, executed for collaboration after the war.

- Legion des volontaires francais contre le bolchevisme(LVF).

- Louis-Ferdinand Céline, writer.

- Mouvement social révolutionnairein 1940.

- Parti Populaire Français(PPF) and member of the LVF.

- Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, writer.

- Henri Lafont

- Gaullist Service d'Action Civique(SAC) in the 1960s.

- Robert Le Vigan, actor.

- Charles Maurras, writer and founder of royalist movement Action Française.

- Lucien Rebatet, writer.

- Pierre Taittinger, chairman of the municipal council of Paris 1943–1944.

See also

- Camp of Septfonds

- Cadix, Allied intelligence center in Uzès

- Collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II

- German occupation of France during World War II

- Government of Vichy France

- Italian occupation of France during World War II

- List of French possessions and colonies

- Military history of France during World War II

- Oradour-sur-Glane

- Ordre Nouveau

- Organisation Todt

- Amy Elizabeth Thorpe

- Western Front (Frankreich) Area (Luftflotte 3, France)

- World War II in the Basque Country

Notes

- ^ Given full constituent powers in the law of 10 July 1940, Pétain never promulgated a new constitution. A draft was written in 1941 and signed by Pétain in 1944 but was never submitted or ratified.[53]

- ^ French: Pétain: "J'entre aujourd'hui dans la voie de la collaboration."

References

- ^ a b c d "Ordonnance du 9 août 1944 relative au rétablissement de la légalité républicaine sur le territoire continental – Version consolidée au 10 août 1944" [Law of 9 August 1944 Concerning the reestablishment of the legally constituted Republic on the mainland – consolidated version of 10 August 1944]. gouv.fr. Legifrance. 9 August 1944. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

Article 1: The form of the government of France is and remains the Republic. By law, it has not ceased to exist.

Article 2: The following are therefore null and void: all legislative or regulatory acts as well as all actions of any description whatsoever taken to execute them, promulgated in Metropolitan France after 16 June 1940 and until the restoration of the Provisional Government of the French Republic. This nullification is hereby expressly declared and must be noted.

Article 3. The following acts are hereby expressly nullified and held invalid: The so-called "Constitutional Law of 10 July 1940; as well as any laws called 'Constitutional Law';... - ISBN 978-2-87027-864-2.

- Julian T. Jackson, France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944 (2001).

- ^ "Le Bilan de la Shoah en France [Le régime de Vichy]". bseditions.fr.

- ISBN 978-0-226-47502-8.

- ^ Simon Kitson. "Vichy Web – The Occupiers and Their Policies". French Studies, University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Kroener 2000, p. iii.

- ^ Kroener 2000, pp. 160–162.

- ISBN 978-1317132691.

The Malgré nous (literally 'in spite of us' or 'against our wishes') was the name given to those inhabitants of the Alsace-Lorraine region forcibly conscripted into the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS.

- ^ Peter Jackson & Simon Kitson ‘The paradoxes of foreign policy in Vichy France’ in Jonathan Adelman(ed), Hitler and his Allies, London, Routledge, 2007

- ^ Langer, William (1947). Our Vichy gamble. Knopf. pp. 364–376.

- ^ "Historique des relations franco-australiennes". 27 September 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006.

- ^ Canada's diplomatic relationships with Vichy: Foreign Affairs Canada Archived 2011-08-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ISBN 978-0-19-992462-2

- ^ Jackson 2001, p. 134.

- ISBN 978-0-691-14297-5. Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ S2CID 57561272.

- ^ a b c Debbie Lackerstein, National Regeneration in Vichy France: Ideas and Policies, 1930–1944 (2013)

- ISBN 978-0-299-08064-8. Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-520-03642-0. Archivedfrom the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- )

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8047-7018-7.

- ^ Flood, Christopher "Pétain and de Gaulle" pp. 88–110 from France At War In the Twentieth Century edited by Valerie Holman and Debra Kelly, Oxford: Berghahan Books, 2000 pp. 92–93

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, pp. 96–98.

- ^ a b c Holman & Kelly 2000, p. 99.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, p. 101.

- ^ Jennings 1994, pp. 712–714.

- ^ Jennings 1994, p. 716.

- ^ a b Jennings 1994, p. 717.

- ^ Jennings 1994, p. 725.

- ^ Jennings 1994, p. 724.

- ^ Cornick, Martyn "Fighting Myth with Reality: The Fall of France, Anglophobia, and the BBC" pp. 65–87 from France At War In the Twentieth Century edited by Valerie Holman and Debra Kelly, Oxford: Berghahan Books, 2000 pp. 69–74.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, p. 69.

- ^ a b Holman & Kelly 2000, p. 70.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, pp. 71–76.

- ^ a b Holman & Kelly 2000, p. 97.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, p. 72.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, p. 75.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Holman & Kelly 2000, p. 76.

- ^ Robert A. Doughty, The Breaking Point: Sedan and the Fall of France, 1940 (1990)

- ^ Jackson 2001, pp. 121–126.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-3571-5. Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Spying for Germany in Vichy France".

- ^ "France". Holocaust Encyclopedia. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Vinen, Richard (2006). The Unfree French: Life under the Occupation. pp. 183–214.

- ^ French Colonial Soldiers in German Prisoner-of-War Camps (1940–1945), Raffael Scheck, 2010, French History, p. 421

- ISBN 978-0-415-92365-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2 November 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Jackson 2001, p. 142.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Maury. "Loi constitutionnelle du 10 Juillet 1940". Mjp.univ-perp.fr. Archived from the original on 23 July 2001. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- OCLC 1058436580. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Constitutional act no. 2, defining the authority of the chief of the French state". Journal Officiel de la République française. 11 July 1940. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8232-2562-0.

- ISBN 2-02-005215-6

- ^ French: L'Assemblée Nationale donne les plein pouvoirs au gouvernement de la République, sous l'autorité et la signature du maréchal Pétain, à l'effet de promulguer par un ou plusieurs actes une nouvelle Constitution de l'État français. Cette Constitution doit garantir les droits du travail, de la famille et de la patrie. Elle sera ratifiée par la nation et appliquée par les Assemblées qu'elle aura créées.

- ^ "Centre for History and Economics". www.histecon.magd.cam.ac.uk.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Maury. "Actes constitutionnels du Gouvernement de Vichy, 1940–1944, France, MJP, université de Perpignan". Mjp.univ-perp.fr. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- OCLC 706628672.

- ^ John F. Sweets, Choices in Vichy France: The French Under Nazi Occupation (New York, 1986), p. 33

- ^ Ousby, Ian Occupation The Ordeal of France, 1940–1944, New York: CooperSquare Press, 2000 p. 83.

- ^ William L. Langer, Our Vichy Gamble (1947)

- ^ a b c d When the US wanted to take over France Archived 27 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Annie Lacroix-Riz, in Le Monde diplomatique, May 2003 (English, French, etc.)

- ^ "Canada and the World: A History". International.gc.ca. 31 January 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ISBN 2-02-031477-0

- ^ Lawrence Journal-World – Aug 22, 1944 Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- Toland, The Rising Sun

- ^ Jouin, Yves (1965). "La Nouvelle-Calédonie et la Polynésie Française dans la Guerre du Pacifique". Revue Historique des Armées. 21 (3): 155–164.

- ^ "Les ÉFO dans la Seconde Guerre Mondiale : la question du ralliement et ses conséquences". Itereva Histoire-Géographie. 5 November 2006. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-1591144786.

- ^ "Citation of the bataillon d'infanterie de marine et du Pacifique for valor during the fourth battle of Monte Cassino". 22 July 1944. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ "Le Bataillon d'infanterie de marine et du Pacifique (BIMP)". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ a b Henri Sautot Order of Liberation

- ^ "Document 3: le choix des Nouvelles-Hébrides". 17 July 2010. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- JSTOR 20530880.

- ^ World War II Pacific Island Guide, p. 71 Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Gordon L. Rottman, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002

- .

- ^ ISBN 0-333-19377-6.

- ^ a b c Guarding the United States and Its Outposts. Center of Military History United States Army. 1964.

- ^ "Eight Allied Ships Sunk Off French Guiana". The Advertiser. 12 March 1943.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Britannica – Guadeloupe". Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Raugh 1993, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Playfair et al. 1954, p. 89.

- ^ Mockler 1984, p. 241.

- ^ Playfair 2004, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Playfair 2004, pp. 323–324.

- S2CID 159589846.

- ^ Arthur L. Funk, The Politics of Torch (1974)

- ^ LDHwebsite (in French)

- ISBN 978-0-19-280700-7.

- Julian T. Jackson, "The Republic and Vichy." in The French Republic: History, Values, Debates (2011): 65–73 quoting p. 65.

- ^ Simon Kitson, The Hunt for Nazi Spies, Fighting Espionage in Vichy France. University of Chicago Press, 2008; the French edition appeared in 2005.

- ISBN 1-85409-290-1

- ^ Jackson 2001, p. 139.

- OCLC 420826274. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016 – via Cairn.info.

- S2CID 226968304.

- ^ François Masure, "État et identité nationale. Un rapport ambigu à propos des naturalisés", in Journal des anthropologues, hors-série 2007, pp. 39–49 (see p. 48) (in French)

- .

Dès juillet 1940, paraissent donc de nouveaux textes qui vont constituer un arsenal législatif antijuif visant en particulier les médecins juifs : la loi du 17 juillet 1940 stipule que, désormais, pour être employé par une administration publique, il faut posséder la nationalité française à titre originaire ; la loi du 22 juillet 1940 établit un processus de révision des naturalisations acquises depuis 1927 ; enfin, la loi du 16 août 1940 réorganise la profession médicale et stipule que « nul ne peut exercer la profession de médecin en France s'il ne possède la nationalité française à titre originaire comme étant né de père français ».

- ISBN 2-87894-026-1

- ISBN 0-8047-2499-7

- ^ Maurice Rajsfus, Drancy, un camp de concentration très ordinaire, Cherche Midi éditeur (2005).

- ISBN 0-674-06888-2.

- ^ "Aincourt, camp d'internement et centre de tri". Archived from the original on 14 July 2006.

- ^ "Saline royale d'Arc et Senans (25) – L'internement des Tsiganes". Cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Listes des internés du camp des Milles 1941". Jewishtraces.org. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Film documentary Archived 28 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine on the website of the Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration (in French)

- ^ "Vichy discrimination against Jews in North Africa". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (ushmm.org). Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Jewish population of French North Africa". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (ushmm.org). 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Jews in North Africa: Oppression and Resistance". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (ushmm.org). Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Jews in North Africa after the Allied Landings". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (ushmm.org). Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "The Holocaust: Re-examining The Wannsee Conference, Himmler's Appointments Book, and Tunisian Jews". Nizkor.org. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ Christoph Buchheim, 'Die besetzten Lander im Dienste der Deutschen Kriegswirtschaft', VfZ, 32, (1984), p. 119

- ^ a b See Reggiani, Alexis Carrel, the Unknown: Eugenics and Population Research under Vichy Archived 4 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, French Historical Studies, 2002; 25: 331–356

- ^ a b c Broughton, Philip Delves (16 October 2003). "Vichy mentally ill patients 'were not murdered'". Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ Gwen Terrenoire, "Eugenics in France (1913–1941) : a review of research findings Archived 18 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine", Joint Programmatic Commission UNESCO-ONG Science and Ethics, 2003

- ^ Quoted in Andrés Horacio Reggiani. Alexis Carrel, the Unknown: Eugenics and Population Research under Vichy Archived 4 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine (French Historical Studies, 25:2 Spring 2002), p. 339. Also quoted in French by Didier Daeninckx in "Quand le négationnisme s'invite à l'université". amnistia.net. Archived from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ Quoted in Szasz, Thomas. The Theology of Medicine New York: Syracuse University Press, 1977.

- ^ French: « ce fichier se subdivise en fichier simplement alphabétique, les Juifs de nationalité française et étrangère ayant respectivement des fiches de couleur différentes, et des fichiers professionnels par nationalité et par rue. »

- ^ The Guardian: Disclosed: the zealous way Marshal Pétain enforced Nazi anti-Semitic laws Archived 1 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, 3 October 2010, last accessed 3 October 2010

- OCLC 1038535440.

- ^ "Drancy". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ISBN 978-2-84405-173-8.

- ^ Maurice Rajsfus, La Police de Vichy. Les Forces de l'ordre françaises au service de la Gestapo, 1940/1944, Le Cherche midi, 1995. Chapter XIV, La Bataille de Marseille, pp. 209–217. (in French)

- ^ ""France" in U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum online Holocaust Encyclopedia". Ushmm.org. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ Azéma, Jean-Pierre and Bédarida, François (dir.), La France des années noires, 2 vol., Paris, Seuil, 1993 [rééd. Seuil, 2000 (Points Histoire)]

- ^ a b c Le rôle du gouvernement de Vichy dans la déportation des juifs, notes taken by Evelyne Marsura during a conference of Robert Paxton at Lyon on 4 November 2000 (in French)

- ^ Summary from data compiled by the Association des Fils et Filles des déportés juifs de France, 1985.

- S2CID 181982155. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "France opens WW2 Vichy regime files". BBC News. 28 December 2015. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ Allocution de M. Jacques CHIRAC Président de la République prononcée lors des cérémonies commémorant la grande rafle des 16 et 17 juillet 1942 (Paris) Archived 13 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Président de la république

- ^ "Allocution de M. Jacques CHIRAC Président de la République prononcée lors des cérémonies commémorant la grande rafle des 16 et 17 juillet 1942 (Paris)" (PDF). www.jacqueschirac-asso (in French). 16 July 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Israel PM mourns France's deported Jews". BBC News. 16 July 2017. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b Hoffmann, Stanley (1974). "La droite à Vichy". Essais sur la France: déclin ou renouveau?. Paris: Le Seuil.

- OCLC 1065422517.

In France, collaborationists were committed to the victory of the Third Reich and actively worked toward that end.

- OCLC 1004807892.

Collaborationists openly embraced fascism. ...They had to continue to believe in German victory or cease to be collaborationists.

- ISBN 978-2-262-02229-7.

- ^ Philip Manow, "Workers, farmers and Catholicism: A history of political class coalitions and the south-European welfare state regime". Journal of European Social Policy 25.1 (2015): 32–49.

- OCLC 757514437.

- ^ Hans Petter Graver, "The Opposition", in Judges Against Justice (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2015) pp. 91–112.

- S2CID 145622142.

- JSTOR 286424.

- ISBN 978-0-312-04773-3.

- ISBN 978-0-415-14219-9.

- JSTOR 20530987.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-582-29909-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7139-9964-8.

- PMID 20672479.

- PMID 20672479.

- ISBN 978-0-300-04774-5.

- ISBN 978-0-226-67349-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8223-2777-6.

- ^ Jackson 2001, pp. 331–332.

- JSTOR 286436.

- ^ Jackson 2001, pp. 567–568.

- ^ Béglé 2014.

- ^ Aron 1962, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Aron 1962, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Cointet 2014, p. 426.

- ^ a b Jean-Pierre Maury. "Ordonnance du 9 août 1944 relative au rétablissement de la légalité républicaine sur le territoire continental". Mjp.univ-perp.fr. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Maury. "Ordonnance du 21 avril 1944 relative à l'organisation des pouvoirs publics en France après la Libération". Mjp.univ-perp.fr. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Flemish Legion Military and Feldpost History". Axis and Foreign Volunteer Legion Military Awards & Postal History. Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ "Accession Plans". german-foreign-policy.com. 11 December 2007. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ Helm, Sarah (16 February 1996). "War memories widen Belgium's communal rift". The Independent on Sunday. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ISBN 978-82-518-0917-7.

- ^ "Vichy France Facts". World War 2 Facts. Archived from the original on 13 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ René Bousquet devant la Haute Cour de Justice Archived 3 December 2002 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- ^ Kitson, Simon. "Bousquet, Touvier and Papon: Three Vichy personalities" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-78478-134-7.

- from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

Bibliography

English

- Atkin, Nicholas, Pétain, (Longman, 1997)

- Azema, Jean-Pierre. From Munich to Liberation 1938–1944 (The Cambridge History of Modern France) (1985)

- Azema, Jean-Pierre, ed. Collaboration and Resistance: Images of Life in Vichy France 1940–1944 (2000) 220pp; photographs

- Boyd, Douglas. Voices from the Dark Years: The Truth About Occupied France 1940–1945 (The History Press, 2015)

- Burrin, Philippe. France Under the Germans: Collaboration and Compromise (1998)

- ISBN 0-375-41131-3; Biography of Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, the Commissioner for Jewish Affairs

- Campbell, Caroline. "Gender and Politics in Interwar and Vichy France." Contemporary European History 27.3 (2018): 482–499. online

- Christofferson, Thomas R., and Michael S. Christofferson. France during World War II: From Defeat to Liberation (2nd ed. 2006) 206pp; brief introduction online edition Archived 14 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Davies, Peter. France and the Second World War: Resistance, Occupation and Liberation (Introduction to History) (2000) 128pp excerpt and text search

- Diamond, Hanna. Women and the Second World War in France, 1939–1948: Choices and Constraints (1999)

- Diamond, Hanna, and Simon Kitson, eds. Vichy, Resistance, Liberation: New Perspectives on Wartime France (2005) online edition Archived 5 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine; online review

- Fogg, Shannon Lee. The Politics of Everyday Life in Vichy France: Foreigners, Undesirables, and Strangers (2009), 226pp excerpt and text search

- Gildea, Robert. Marianne in Chains: Daily Life in the Heart of France During the German Occupation (2004) excerpt and text search

- Glass, Charles, Americans in Paris: Life and Death Under Nazi Occupation (2009) excerpt and text search

- Gordon, B. Historical Dictionary of World War Two France: The Occupation, Vichy and the Resistance, 1938–1946 (Westport, Conn., 1998)

- Halls, W. D. Politics, Society and Christianity in Vichy France (1995) online edition Archived 13 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Holman, Valerie; Kelly, Debra (2000). France at War in the Twentieth Century: Propaganda, Myth, and Metaphor. Contemporary France (Providence, R.I.). New York: Berghahn Books. OCLC 41497185.

- Jackson, Julian T. (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820706-1. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Jennings, Eric (1994). "'Reinventing Jeanne': The Iconology of Joan of Arc in Vichy Schoolbooks, 1940–44". The Journal of Contemporary History. 29 (4): 711–734. S2CID 159656095.

- Kedward, H. R. Occupied France: Collaboration and Resistance (Oxford, 1985), short survey

- ISBN 978-0-226-43893-1.

- Kocher, Adam, Adria K. Lawrence and Nuno P. Monteiro. 2018. "Nationalism, Collaboration, and Resistance: France under Nazi Occupation." International Security 43(2): 117–150.

- Kooreman, Megan. The Expectation of Justice: France, 1944–1946. (Duke University Press. 1999)

- Kroener, Bernhard R.; Muller, Rolf-Dieter; Umbreit, Hans (2000). Germany and the Second World War: Volume 5: Organization and Mobilization of the German Sphere of Power. Part I: Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources, 1939–1941. Germany & Second World War. OUP Oxford. p. iii. OCLC 1058510505. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- Lackerstein, Debbie. National Regeneration in Vichy France: Ideas and Policies, 1930–1944 (2013) excerpt and text search

- Langer, William, Our Vichy gamble, (1947); U.S. policy 1940–42

- Larkin, Maurice. France since the Popular Front: Government and People 1936–1996 (Oxford U P 1997). ISBN 0-19-873151-5

- Lemmes, Fabian. "Collaboration in wartime France, 1940–1944", European Review of History (2008), 15#2 pp 157–177

- Levieux, Eleanor (1999). Insiders' French : beyond the dictionary. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-47502-8.

- Manow, Philip. "Workers, farmers and Catholicism: A history of political class coalitions and the south-European welfare state regime". Journal of European Social Policy (2015) 25#1 pp: 32–49.

- Marrus, Michael R. and Robert Paxton. Vichy France and the Jews. (Stanford University Press, 1995). online 1981 edition Archived 11 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Martin Mauthner. Otto Abetz and His Paris Acolytes – French Writers Who Flirted with Fascism, 1930–1945. (Sussex Academic Press, 2016). ISBN 978-1-84519-784-1

- Melton, George E. Darlan: Admiral and Statesman of France, 1881–1942. (Praeger, 1998). ISBN 0-275-95973-2.

- Mockler, Anthony (1984). Haile Selassie's War: The Italian−Ethiopian Campaign, 1935–1941. New York: ISBN 978-0-394-54222-5.

- Nord, Philip. France's New Deal: From the Thirties to the Postwar Era (Princeton U.P., 2010)

- Michel, Alain (2014) [1st pub. 2011]. "10 Collaboration and collaborators in Vichy France: An unfinished debate". In Stauber, Roni (ed.). Collaboration with the Nazis: Public Discourse after the Holocaust. Routledge Jewish Studies series. London: Routledge. OCLC 876293139.

- Paxton, Robert O. Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 (2nd ed. 2001) excerpt and text search; influential survey

- OCLC 494123451. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004) [1956]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Germans Come to the Help of their Ally (1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. II (pbk. repr. Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-066-5.

- Pollard, Miranda. Reign of virtue: mobilising gender in Vichy France (University of Chicago Press, 2012)

- Raugh, H. E. (1993). Wavell in the Middle East, 1939–1941: A Study in Generalship. London: Brassey's. ISBN 978-0-08-040983-2.

- Smith, Colin. England's Last War Against France: Fighting Vichy, 1940–1942, London, Weidenfeld, 2009. ISBN 978-0-297-85218-6

- Sutherland, Jonathan, and Diane Canwell. Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II (Pen & Sword Aviation, 2011)