Village East by Angelika

| |

| |

| Former names | List

|

|---|---|

| Address | 181–189 Astor Place |

| Owner | Senyar Holding Company |

| Operator | City Cinemas (Reading International); Angelika Film Center |

| Type | Yiddish, Off-Broadway |

| Screens | 7 |

| Current use | Movie theater |

| Construction | |

| Architect | Harrison Wiseman |

| Website | |

| www | |

Yiddish Art Theatre | |

| No. 1764, 1765 | |

New York, New York | |

| Coordinates | 40°43′51″N 73°59′11″W / 40.73083°N 73.98639°W |

| Area | 12,077 sq ft (1,122.0 m2) |

| Built | 1926 |

| Architect | Harrison G. Wiseman |

| Architectural style | Moorish |

| NRHP reference No. | 85002427[1] |

| NYCL No. | 1764, 1765 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 19, 1985 |

| Designated NYCL | February 9, 1993 |

Village East by Angelika (also Village East, originally the Louis N. Jaffe Art Theatre, and formerly known by several other names

Village East's main entrance is through a three-story office wing on Second Avenue, which has a facade of cast stone. The auditorium is housed in the rear along 12th Street. The first story contains storefronts and a lobby, while the second and third stories contained offices, which were converted into apartments in the 1960s. The main lobby connects to another lobby along 12th Street with a promenade behind the auditorium. The auditorium consists of a ground-level orchestra and one overhanging balcony with boxes. The balcony remains in its original condition, but the orchestra and former stage area have been divided into six screens.

The Louis N. Jaffe Art Theatre was originally used by the Yiddish Art Theatre and largely served as a Yiddish playhouse from 1926 to 1945. It opened on November 17, 1926, with The Tenth Commandment. The Yiddish Art Theatre moved out of the theater after two seasons, and it became the Yiddish Folks Theatre. The venue was leased by Molly Picon in 1930–1931 and by Misha and Lucy German in 1931–1932. The Yiddish Arts Theatre then performed at the theater until 1934, after which the Yiddish Folks continued for two more years. From 1936 to 1944, the building was a movie theater called the Century Theatre, hosting Yiddish performances during two seasons.

After a decline in Yiddish theater, the Jaffe Art Theatre was renamed the Stuyvesant Theatre in 1946 and continued as a movie theater for seven years. The then-new Phoenix Theatre used the playhouse from 1953 to 1961. The Jaffe Art Theatre then became the Casino East Theatre, which hosted the burlesque production This Was Burlesque for three years before becoming a burlesque house called the Gayety Theatre in 1965. The theater was renamed yet again in 1969, this time operating as the off-Broadway Eden Theatre until 1976, showing the revue Oh! Calcutta!. The venue was then converted into a movie theater, the 12th Street Cinema, before returning to live shows in 1977 under the name Entermedia Theatre (renamed the Second Avenue Theatre in 1985). After closing in 1988, the Jaffe Art Theatre was renovated into Village East Cinema, reopening in 1991. Angelika rebranded the theater in 2021.

Description

Village East, originally the Yiddish Art Theatre, is at the southwestern corner of East 12th Street and Second Avenue in the East Village of Manhattan in New York City, within the former Yiddish Theatre District.[3][4] The theater occupies a rectangular land lot of 12,077 square feet (1,122.0 m2),[5] with a frontage of 103 feet (31 m) on Second Avenue and 117.25 feet (36 m) on 12th Street.[6][7] It is composed of two sections: a three-story office wing with a cast-stone facade, facing east on Second Avenue, as well as an auditorium wing with a brown-brick facade, extending westward along 12th Street.[8] The site is a block north of St. Mark's Church.[5][9]

The theater was built by Louis Jaffe, a developer and prominent Jewish community leader, for

Facade

On the building's Second Avenue elevation, the first two stories consist of a double-height

The other six arches are identical round-arched openings and are separated by paneled

The easternmost portion of the 12th Street elevation contains two bays of double-height arches and paired windows, similar to those in the Second Avenue elevation. The steel-framed auditorium structure is clad in brick.[8] The outer portions of the auditorium facade are treated as pavilions. They are slightly taller than the rest of the auditorium and protrude slightly from the central section of the facade. Each outer pavilion contains a metal gate at ground level, above which is an arched opening with a fire stair behind it.[17] The center of the facade contains a cast-stone doorway surrounding five sets of exit doors.[8] There is a carved corbel on either side of the doorway.[15] Above the doors is a blind brick arch, surrounding a panel with pink terracotta quatrefoils.[8] The top of the auditorium facade is made of a band of cast stone.[17] An alley runs to the west of the theater.[18]

Interior

The interior is decorated in a gold, blue, rose, cream, and silver color scheme. Many of the interior decorations are inspired by the Alhambra in Spain.[19] The decorations also contain elements of Moorish, Islamic, and Judaic architecture.[19][20] Most decorations resemble their original condition, even though the layout of the theater has been substantially changed.[12][19] The interior of Village East was used as a filming location for the films The Night They Raided Minsky's in 1968 and The Fan in 1981,[15] as well as a promotional video for Reese's Peanut Butter Cups in 1984.[21]

Lobbies

The theater has two lobbies. The main one on Second Avenue was a square space[4] (subsequently expanded to a rectangular space), while a secondary lobby on 12th Street provides access to the balcony level.[19] When the theater was converted into a movie theater in the early 1990s, all of the floor surfaces were covered or replaced with a carpet containing red, gold, blue, and gray patterns.[22]

Originally, the main lobby had a floor made of terracotta, with a pattern of white rhombus motifs. The box office was on the north wall, while the south wall contained mirrored panels.[4] Only the original ceiling of the main lobby remains intact. The center of the ceiling contains a medallion; the edges of the ceiling contain a frieze with corbels, as well as decorative rectangular and square panels. During the early-1990s renovation, the lobby was expanded southward, and a concession stand and a wall of poster boards were installed.[19] The lobby also contains an exhibit about the history of Yiddish theatre.[23][22]

On the northern side of the theater building, to the right of the main lobby, is the 12th Street lobby.[24] The walls there are buff-colored and are designed to resemble travertine. The exit doors on the north wall contain trefoil arches, corbels, and Moorish exit signs. The ceiling has three circular chandeliers and is ornately designed with floral symbols and circles. The 12th Street lobby connects to a pair of segmentally arched alcoves, inside which are stairs descending to the basement.[19]

On the north wall of the 12th Street lobby, two curved staircases with wrought-iron railings lead up to a narrow promenade behind the balcony-level seating.[19][25] The underside of the balcony promenade (immediately above the 12th Street lobby) contains three medallions, each of which contains six-pointed arabesques, as well as recessed lighting fixtures and a decorative border. Above the promenade are four rectangular panels and one square panel, each with cartouches at its center, in addition to recessed lighting. Small staircases at the western and eastern ends of the promenade lead up to the top of the balcony-level seating.[19]

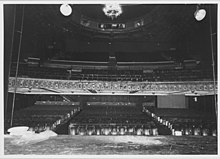

Auditorium

The auditorium has an orchestra level, a balcony, boxes, and a proscenium arch that originally had a stage behind it.[26][27] The auditorium is oriented toward the south, with the rear wall and 12th Street lobby being to the north.[24] The original auditorium contained 1,143,[4] 1,236,[28][29] 1,252,[27] or 1,265 seats.[30] The orchestra level was initially raked, sloping down toward an orchestra pit in front of the stage.[25] The stage originally measured 30 by 36 feet (9.1 by 11.0 m) across.[25]

In 1990, the theater was

The side walls of the auditorium are made of textured plaster and were initially painted in a buff color, though it was subsequently repainted blue-gray. The front of the balcony is decorated with rosettes and round-arched panels, atop which are a parapet and railing. After the original auditorium was multiplexed, a lower balcony was created in front of the original balcony, connected to it by double staircases. The lower balcony has an exit to the promenade, directly below the original balcony, as well as a ramp leading to an exit on the north wall.

The middle of the ceiling contains a shallow circular dome measuring 40 feet (12 m) across.[32][35] At the center of the dome is a medallion with the Star of David, which is enclosed within a larger six-pointed star with trefoils at its "points". A metal chandelier with two tiers hangs from the center of the dome.[10][36] The outer border of the dome is decorated with wrought-iron grilles and motifs of the Star of David.[25] There are also fascia panels around the dome, some of which have been modified to accommodate projection equipment and ventilation openings.[10][19] Outside of the dome, the ceiling contains ornate gilded plaster moldings.[10][36] The decoration is intended to resemble a honeycomb and contains rosettes, eight-pointed stars, and strapwork. There are ducts near where the ceiling intersects with the walls.[19] The ceiling is actually made of 3-by-3-foot (0.91 by 0.91 m) panels suspended from the roof via iron bars.[10]

Other spaces

Above the stage were twelve dressing rooms, as well as access to the space above the dome. Under the stage were offices, storage rooms, and access to the orchestra pit. In addition, the theater's restrooms, lounge, and administrative offices were in the basement behind the auditorium (near 12th Street).[25] The lounge contained busts of prominent playwrights and performers in Yiddish theatre, such as Abraham Goldfaden, David Kessler, Jacob Pavlovich Adler, Jacob Gordin, and Sholem Aleichem.[37] The basement also included a restaurant and cabaret/nightclub.[28][38][39]

The second and third stories along Second Avenue contained rehearsal rooms. These were accessed from the third bay from north, just left of the main entrance.

History

During the 1880s, New York City's

Development and opening

In May 1925, Jaffe acquired a site on 12th Street and Second Avenue, formerly part of the

Wiseman filed plans with the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) at the end of May 1925, shortly after Jaffe acquired the site.[49][55] The building was to cost $235,000. The DOB initially objected to the project because of its location within a residential neighborhood, the lack of exits to the west, and the absence of a setback along Second Avenue.[56] Site-clearing began the next month,[49] and five old houses were torn down to make way for the theater.[9] Olga Loev, widow of Sholem Aleichem,[52][57] laid the theater's cornerstone at a ceremony on May 23, 1926.[53][57] Playwright Herman Bernstein said that the event was "of magnitude for Jews in America", given the Yiddish Art Theatre's success in spite of early difficulties.[52][57] Portraits of Abraham Goldfaden (the "father of the Yiddish theatre movement") and Peter Stuyvesant (the owner of the Stuyvesant Farm) were placed inside the cornerstone.[57] Jaffe said he wanted the theater to be "a permanent monument to prove that the Jewish immigrant to [the United States] is a useful citizen and makes a definite contribution to the country", responding to anti-Semitic comments that Stuyvesant had made three centuries prior.[58]

By mid-1926, the Jaffe Art Theater was expected to open that September,[59] but it remained closed past that date. Schwartz then planned to open the theater on November 11 with The Tenth Commandment, his adaptation of Goldfaden's play Thou Shalt Not Covet.[30][37][60] Before the theater opened, the New York Herald Tribune called it "a lasting monument to Yiddish art",[60] while The New York Times said the theater building "will be the most attractive amusement structure in that locality".[59] The Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater opened on November 17, 1926, with The Tenth Commandment. In the opening-night program, Schwartz described the theater's opening as the "culmination of a lifelong dream".[61][62] The opening-night visitors included theatrical personalities such as Daniel Frohman, Owen Davis, and Robert Milton, as well as non-theatrical notables such as Otto Kahn and Fannie Hurst.[62][63] The theater, which cost $1 million to construct, was not officially completed until January 8, 1927.[52]

Yiddish shows

The Jaffe Art Theatre was one of the last Yiddish theaters to open on Second Avenue, having been completed just as Yiddish theater was starting to decline.

1920s

For the rest of the 1926–1927 season, the Jaffe Art Theatre was occupied by limited runs of six productions: Mendele Spivak in 1926[66][67] and Her Crime, Reverend Doctor Silver, Yoske Musicanti, Wolves, and Menschen Shtoib in early 1927.[66] After a summer hiatus,[68] the theater then reopened the 1927–1928 season with the play Greenberg's Daughters in September 1927.[69] The season also featured the play The Gardener's Dog, the first American production by Boris Glagolin's Moscow Revolution Theater.[66][70] Other plays of that season included The Gold Diggers and On Foreign Soil in late 1927, as well as Alexander Pushkin and American Chasidim in early 1928.[66] Schwartz appeared in many of these plays.[66] Despite high expectations, the theater performed worse than expected in its first two seasons.[71][72] Among the reasons for this were the rise of talking pictures, negotiations with performers' unions, and a decline in Jewish immigration.[71]

In April 1928, Jaffe leased the theater to the Amboard Theatre Corporation, headed by Morris Lifschitz.[72] The next month, the Louis N. Jaffe Art Theatre Corporation sold the theater to a client of Jacob I. Berman.[73][74] The Yiddish Art Theatre moved out after two seasons[75][76] because Schwartz had severed his agreement with Jaffe.[75] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) stated that the Jaffe Art Theatre remained vacant for the 1928–1929 season,[77] but contemporary news reports indicate that the Yiddish Folk Theatre occupied the building during that season, starting with a dance recital in September 1928.[75][78] The Yiddish Folks Theatre gave at least two other performances at the theater, both directed by Ludwig Satz.[66] His Wife's Lover opened in October 1929,[79][80] followed by If the Rabbi Wants that December.[81][82]

1930s

The comedienne Molly Picon leased the Jaffe Art Theatre in June 1930,[83][84] and it was renamed Molly Picon's Folks Theatre.[77] Isaac Lipshitz acquired the theater in a foreclosure proceeding that August,[71][85] and the play The Girl of Yesterday opened the next month, starring Picon.[86][87] This was followed in January 1931 by the play The Love Thief, also starring Picon.[88][89] Prosper Realty Corporation was recorded as taking ownership of the theater that February.[77] Misha and Lucy German (also spelled Gehrman[90]) leased the theater in May 1931, and the theater was rebranded yet again as the Germans' Folks Theatre.[77][91] Under the German family's ownership, the theater hosted at least four performances: One Woman in 1931[92][93] and In a Tenement House, Pioneers, and Wedding Chains in 1932.[92]

The Yiddish Art Theatre returned to the theater after Schwartz leased it for the 1932–1933 season.[94][95] The company opened the season with Yoshe Kalb, which ran for 235 performances at the theater[96] and was then performed on Broadway in English,[77][97] for a total of 300 performances.[98] Other Yiddish plays performed in 1932–1933 included Chayim Lederer, Legend of Yiddish King Lear, Bread, and Revolt. Schwartz also leased the theater for the 1933–1934 season, when he hosted Wise Men of Chelm, Josephus, and Modern Children.[94] The theatrical company departed in April 1934, and the venue again became the Yiddish Folks Theatre, since Schwartz owned the rights to the "Yiddish Art Theatre" name.[77][90] Under the direction of Joseph Buloff, the New York Art Troupe leased the theater for the 1934–1935 season,[99][100] hosting eight plays there.[94]

Menasha Skulnik and Joseph M. Rumshinsky signed a lease for the theater in April 1935,[101] then announced plans to lease the theater as a movie house "until the fall".[102] One newspaper proclaimed that the Yiddish Folks Theatre would become the world's first movie theater that hosted films exclusively in Yiddish, though it is unknown whether this ever happened.[77] The first live show that Skulnik and Rumshinsky hosted at the theater was Fishel der Gerutener (English: "The Perfect Fishel"), which opened in September 1935.[103][104] The men hosted three other shows: Schlemiehl in September 1936,[105][106] Straw Hero in November 1936,[107][108] and The Galician Rabbi in 1937.[109][110]

Decline and film conversion

By the late 1930s, the popularity of Yiddish theatre was starting to wane. Various reasons were cited for the decline, including a slowdown in the number of Jewish immigrants after World War I and the fact that younger Jews were blending in with American culture.[111][112] In addition, the city's Jewish population dispersed from the Lower East Side and East Village.[112] By March 1937, just ten years after the Yiddish Folks Theatre had opened, independent film operators Weinstock and Hertzig planned to lease the theater for movies.[113] Saulray Theatres Corporation leased the theater the next month,[77] and it became a movie theater called the Century.[31][77] The conversion occurred as similar Yiddish venues in the East Village and Lower East Side had become movie houses.[112] Shortly after the Century reopened, its sound equipment was replaced.[114] The theater went into foreclosure by September 1937 and was taken over by the Greater New York Savings Bank.[77]

In June 1940, the Yiddish Folks Theatre leased the Century for one season.[115][116] The Yiddish Folks Players then presented Sunrise that October,[104][117] followed by Sixty Years of Yiddish Theatre, a musical in honor of Rumshinsky, in January 1941.[118][119] The troupe's manager Jacob Wexler died in the middle of the 1940–1941 season, and Ola Lilith took over the troupe's management.[115] The third and final Yiddish show of the season was A Favorn Vinkel ("The Forsaken Nook") in February 1941,[104] with a special performance in honor of Ludwig Satz.[120][121] The Century's operators announced that March that they would return the theater to a film policy, showing three American feature films every day.[122][123] After a renovation, the Century screened the feature film Gone with the Wind that April.[115][124] In addition, O'Gara & Co. Inc. was hired to lease out the office space on Second Avenue.[125]

In 1942, the Greater New York Savings Bank leased the theater to the Century Theatre Company for ten years.[126][127] The bank then leased the Jaffe Art Theatre in January 1944 to Benjamin Benito, who planned to stage Italian opera and vaudeville there.[128] The Raynes Realty Company acquired the theater from the bank that September and discontinued Benito's lease.[38][39] Jacob Ben-Ami's New Jewish Folk Theater leased the theater during the 1944–1945 season, operating it as the Century Theatre.[129][130] Ben-Ami presented two shows, The Miracle of the Warsaw Ghetto by H. Leivick and We Will Live by David Bergelson, in what was the theater's last season as a Yiddish theatrical venue.[115] By then, many Yiddish speakers had been murdered in the Holocaust, further contributing to the decline in Yiddish theatre.[111][131] The Jaffe Art Theatre then reopened as a 1,082-seat movie theater, the Stuyvesant Theatre, around March 1946. The theater continued to screen films until 1953.[31][115]

Off-Broadway use

Phoenix Theatre era

In October 1953, Norris Houghton and T. Edward Hambleton formed the Phoenix Theatre company and leased the Jaffe Art Theatre, initially for a series of five plays.[132][133] The Phoenix Theatre was a pioneering project in the development of off-Broadway, with a different approach to legitimate theatre than found on Broadway. Houghton and Hambleton had wanted a theater away from Broadway's Theater District. The Jaffe Art Theatre had appealed to them because it was newer than most Broadway venues and also because it was close to Stuyvesant Town–Peter Cooper Village, which had 30,000 residents. The group planned to charge a relatively cheap $1.20 to $3.00 per ticket; in return, performers would not be paid more than $100 per week, and each show would have a four-week limited run.[115][134] A writer for Variety described Phoenix's formation as "one of the most important off-Broadway developments of recent years".[135]

Phoenix's first production was Sidney Howard's play Madam, Will You Walk?, which opened in December 1953 with Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy.[136] Other notable shows of the 1953–1954 season included Coriolanus, The Golden Apple, and The Seagull.[104] The troupe's first season was successful; The Golden Apple transferred to Broadway, while The Seagull was sold out through its limited run.[137] This prompted Houghton to renew his lease on the theater.[138] The 1954–1955 season included the plays Sing Me No Lullaby, The Doctor's Dilemma, and The Master Builder,[139] as well as the revue Phoenix '55.[140][141] The theater also started hosting Sideshows, a set of "programs of diverse entertainment", on Monday nights during that season.[142] Additionally, air-conditioning was installed in the theater around 1955 so shows could be presented there during the summer.[140] The presence of the Phoenix Theatre and other off-Broadway companies on Second Avenue contributed to a revival of the former theatrical hub there.[143]

During the 1955–1956 season, Phoenix presented plays from aspiring directors at the Jaffe Art Theatre as part of an experimental program.

For the 1958–1959 season, Phoenix decided to book plays by Nobel Prize-winning writers such as T. S. Eliot.[148][149] The plays during that season included The Family Reunion, Britannicus, The Power and the Glory, The Beaux' Stratagem, and Once Upon a Mattress.[150] After launching a drive to enroll new subscribers in April 1959,[151] the theatrical company enrolled 9,000 subscribers and obtained $150,000 in subsidies by that June.[152] This enabled Phoenix to pre-select all of the plays in a season, rather than booking plays as the season progressed, for the first time in the troupe's history.[153] The theater then hosted plays such as Lysistrata, Peer Gynt, and part 1 and part 2 of Shakespeare's Henry IV during 1959–1960.[150][154] Phoenix's last full season at the theater, in 1960–1961, consisted of H.M.S. Pinafore, She Stoops to Conquer, The Plough and the Stars, The Octoroon, and Hamlet.[150] The company relocated to the much smaller 74th Street Theater in late 1961 after The Pirates of Penzance, the first play of the 1961–1962 season, was staged at the Second Avenue theater.[155][156] This move was prompted by the fact that, after its first season, Phoenix had consistently operated at a loss and could not fill the Jaffe Art Theatre.[157]

Burlesque and nude era

In November 1961, Michael Iannucci and Milton Warner leased the Jaffe Art Theatre for one year, with an option to renew for another year.[158] The next month, the theater was renamed the Casino East Theater[140] and reopened with a Yiddish-language show, Gezunt un Meshuga ("Hale and Crazy").[159][160][161] By then, it had 1,150 seats.[159] In March 1962, Casino East hosted the satirical burlesque production This Was Burlesque starring Ann Corio.[162][163] During this time, Iannucci managed the front of house, or the publicly accessible parts of the theater. Corio oversaw the stage and backstage operations, with a speaker in her dressing room that allowed her to hear everything on stage.[164] The revue was successful, ultimately lasting 1,509 performances at the Casino.[150][165] This Was Burlesque ultimately relocated to the Hudson Theatre on Broadway in March 1965.[166][167] Corio said that tourists could not find Casino East and that ticket sellers could more easily sell tickets to the show if it were on Broadway.[168]

Afterward, Casino East became the Gayety Theater,[140][169] the only burlesque theater in Manhattan.[140][170] The venue was operated by Leroy Griffith, who had opened the burlesque venue there following the success of Corio's show.[169] The operator charged $4 admission, higher than at the Hudson Theatre.[171] The off-Broadway production Oh! Calcutta!, a revue in which all the cast members were nude, was announced for the theater in April 1969, upon which point the venue was renamed the Eden Theater.[172][173] The revue's producer George Platt explained the renaming by saying, "We're not doing a burlesque show, we're doing a legitimate show."[173] Oh! Calcutta! opened at the theater in June 1969.[174][175] While the Eden was as large as a standard Broadway theater, Oh! Calcutta! used an off-Broadway contract that limited the audience to 499 seats;[176] nonetheless, the show made a profit at the Eden.[177] The revue moved to Broadway's Belasco Theatre in February 1971[178] after running for 704 performances.[179]

Yiddish revival and legitimate shows

In March 1971 the Broadway musical Man of La Mancha moved from the Martin Beck Theatre to the Eden.[176][180] La Mancha operated under a Broadway contract, which allowed all of the Eden's seats to be used;[176] the musical moved to Broadway's Mark Hellinger Theatre after three months.[181] That June, Jacob Jacobs leased the Eden with plans to host Yiddish shows there.[182] Next, the rock musical Grease opened in February 1972[183][184] under a Broadway contract that allowed all seats to be used.[185] The musical moved to the Broadhurst Theatre that June[186] and later became Broadway's longest-running musical.[185] By then, Jewish Nostalgic Productions was raising funds for a series of Yiddish plays at the Eden.[187]

The revue Crazy Now opened at the Eden in September 1972,[188][189] followed the next month by a revival of Yoshe Kalb.[190][191] In early 1973, the theater also hosted a dance special by Larry Richardson[192] and the Broadway musical Smith,[193][194] the latter of which relocated to the Alvin Theatre.[195] Jewish Nostalgic Productions staged several more shows, of which three had more than 100 performances.[179] For the 1973–1974 season, the Eden was occupied by Aleichem's play Hard To Be a Jew.[196][197] This was followed in the 1974–1975 season by another Aleichem play, Dos Groyse Gevins ("The Big Winner"),[198][199] as well as a short run of A Wedding in Shtetel.[200] Senyar Holding Company, a firm owned by Martin Raynes, took ownership of the theater in March 1975.[140] During the 1975–1976 season, the Eden hosted Sylvia Regan's musical The Fifth Season.[201][202] The theater had become the 12th Street Cinema by mid-1976,[203] but this use only lasted a short time.[140]

By September 1977, the Jaffe Art Theatre was known as the Entermedia Theater.

Entermedia left the theater in 1985, and the venue was leased to M Square Productions, which renamed it the Second Avenue Theater.[140][65] It was one of M Square's three off-Broadway houses. M Square's managing director Alan J. Schuster said the company wanted "to have a legitimate theater and a film theater at the Second Avenue" without incurring the exorbitant costs of Broadway theatre contracts.[218] The movie theater would have been above the legitimate theater, but these plans never materialized.[65] The Second Avenue hosted Zalmen Mlotek and Moishe Rosenfeld's bilingual revue The Golden Land, which opened in November 1985[219][220] and ran for 277 regular performances.[221][b] For the 1986–1987 season, the theater staged the musical Have I Got a Girl for You!, which opened in November 1986,[222][223] and the musical Staggerlee, which opened in March 1987.[224][225] The theater also hosted a tribute to the late off-Broadway actor Charles Ludlam in mid-1987.[226] The Chaim Potok play The Chosen opened in January 1988[227][228] but flopped with just six regular performances.[65][229][b]

Village East use

EverGreene Architectural Arts restored the theater at the beginning of 2015.[10][234] The work involved replacing some of the historical design features that had deteriorated over the years.[234] The theater closed temporarily in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. When the theater reopened on March 5, 2021,[235][236] it was rebranded as Village East by Angelika.[237] After Village East reopened, several movies were screened in 70 mm.[238] A new bar and kitchen were announced for the theater in late 2021.[239] By 2022[update], the theater generally screened newly released films, though it sometimes showed revivals as well.[240] Among these is the premiere of Tommy Wiseau's second film Big Shark, which is set to take place at the theater in August 2023.[241]

Notable productions

Productions are listed by the year of their first performance. This list only includes theatrical shows; it does not include films, burlesque shows, or other types of live performance.

- 1954: Coriolanus[242][243]

- 1954: The Golden Apple[244]

- 1954: The Seagull[245][246]

- 1954: Sing Me No Lullaby[247]

- 1955: The Doctor's Dilemma[248]

- 1955: The Master Builder[249]

- 1955: Marcel Marceau[250][251]

- 1955: Six Characters in Search of an Author[252][253]

- 1956: The Adding Machine[254][255]

- 1956: Miss Julie/The Stronger[256][257][c]

- 1956: A Month in the Country[258][259]

- 1956: Saint Joan[260][261]

- 1956:

- 1956:

- 1957: Measure for Measure[266][267]

- 1957: The Taming of the Shrew[268][269]

- 1957: The Duchess of Malfi[270][271]

- 1957: Mary Stuart[272][273]

- 1957: The Makropulos Secret[274][275]

- 1958: The Chairs/The Lesson[276][277][d]

- 1958: The Infernal Machine[278][279]

- 1958: The Two Gentlemen of Verona[280][281]

- 1958: The Broken Jug[280][282]

- 1958: La Malade Imaginaire[150][283]

- 1958: Evening of Three Farces[284][285][e]

- 1958: The Family Reunion[286][287]

- 1958: Britannicus[288][289]

- 1958: The Power and the Glory[290][291]

- 1959: The Beaux' Stratagem[292][293]

- 1959: Once Upon a Mattress[294][295]

- 1959: Lysistrata[296][297]

- 1960: Peer Gynt[298][299]

- 1960: Henry IV, Part 1[300][301]

- 1960: Henry IV, Part 2[302][303]

- 1960: H.M.S. Pinafore[304][305]

- 1960: She Stoops to Conquer[306][307]

- 1960: The Plough and the Stars[308][309]

- 1961: The Octoroon[310][311]

- 1961: Hamlet[312][313]

- 1961: The Pirates of Penzance[150][314]

- 1969: Oh! Calcutta![315][174]

- 1971: Man of La Mancha[176][180]

- 1972: Grease[316][183]

- 1978: The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas[179][206]

- 1979:

- 1981: Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat[179][213]

See also

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan below 14th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

References

Notes

- ^ The theater has also been known as the Louis N. Jaffe Theater, Yiddish Art Theatre, Yiddish Folks Theatre, Molly Picon's Folks Theatre, Germans' Folks Theatre, Century Theatre, New Jewish Folk Theatre, Stuyvesant Theatre, Phoenix Theatre, Casino East Theatre, Gayety Theatre, Eden Theatre, 12th Street Cinema, Entermedia Theater, Second Avenue Theater, and Village East Cinema.[2]

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 21, counts both previews and regular performances. For example, The Golden Land is counted as having 295 performances (including 18 previews), and The Chosen is recorded as having 58 performances (including 52 previews).

- ^ Miss Julie and The Stronger were performed in repertory.[256][257]

- ^ The Chairs and The Lesson were performed in repertory.[276][277]

- ^ Composed of three plays: The Forced Marriage, The Imaginary Cuckold, and The Jealousy of the Barbouille.[285][284]

Citations

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, pp. 6–10.

- ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 1985, p. 2.

- ^ a b "189 2 Avenue, 10003". New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1112808349.

- ^ ProQuest 1031764080.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 10; National Park Service 1985, p. 2.

- ^ ProQuest 103663798.

- ^ a b c d e f Murray, James; Murray, Karla (January 27, 2017). "The Urban Lens: Inside the Village East Cinema, one of NY's last surviving 'Yiddish Rialto' theaters". 6sqft. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Amanda Seigel (March 18, 2014). "The Yiddish Broadway and Beyond". New York Public Library. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4384-3769-9.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1985, p. 4.

- ^ Nahshon 2016, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 13.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1993, p. 11.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ProQuest 1438553105.

- ^ ProQuest 1040614810.

- ^ a b Bloom, Steve (March 30, 1990). "Manhattan Moviemania". Newsday. pp. 180, 181. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1993, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 1985, p. 3.

- ^ National Park Service 1985, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1993, p. 10.

- ^ a b Nahshon 2016, p. 34.

- ^ ProQuest 367724880.

- ^ ProQuest 1676859863.

- ^ a b c d e Melnick, Ross (December 1, 2015). "City Cinemas Village East". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "City Cinemas Village East Cinema". The Village Voice. NYC & Company. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1993, p. 11; National Park Service 1985, p. 2.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1993, p. 11; National Park Service 1985, p. 3.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1318080433.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 2.

- ^ National Park Service 1985, p. 5.

- ISBN 9781878741622. Retrieved March 10, 2013; Cofone, Annie (September 13, 2010). "Theater District; Strolling Back Into the Golden Age of Yiddish Theater". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "East Village/Lower East Side Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 9, 2012. p. 31. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ National Park Service 1985, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1985, p. 9.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 5.

- ^ a b Zylbercweig, Zalmen, ed. (1959). לעקסיקאן פון יידישן טעאטער [Lexicon of Yiddish Theatre] (in Yiddish). Vol. 3. New York: Hebrew Actors' Union; Elisheva. cols. 2334-2340.

- ^ National Park Service 1985, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 3.

- ProQuest 103612193.

- ProQuest 1112936188.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 4.

- ^ ProQuest 1031790129.

- ProQuest 1031761165.

- ProQuest 1031756994.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, pp. 3–4.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 12.

- ^ ProQuest 103751911.

- ^ ProQuest 1112652012.

- ProQuest 1112646060.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 14.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Firestone, David (August 2, 1988). "Yiddish Theater: Closing of an Era". Newsday. pp. 115. 116, 135. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 15.

- ProQuest 1677121263.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ProQuest 1131514008.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1113715437.

- ^ ProQuest 1475750456.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 6.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1475752171.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 7.

- ProQuest 1113496447.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ProQuest 1111672192.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ProQuest 1112019187.

- ProQuest 1727884955.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ProQuest 1113707952.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ProQuest 1114163789.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "Gehrmans Back in Brooklyn with Revised Comedy". New York Daily News. April 10, 1934. p. 346. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, pp. 15–16.

- ProQuest 1125422011.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 16.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ Nahshon 2016, p. 45.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 7; National Park Service 1985, p. 10.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Hartman, Walter (September 25, 1934). "Molly Picon and Art Troupe Open Yiddish Season". New York Daily News. p. 386. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Theatre Notes". New York Daily News. April 30, 1935. p. 38. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Yiddish Road Shows Featured". New York Daily News. May 13, 1935. p. 77. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 17.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ProQuest 1222099844.

- ^ "New Offerings, Extra Shows in Yiddish Houses". New York Daily News. November 24, 1936. p. 42. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ProQuest 1246944967.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1985, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, pp. 7–8.

- ProQuest 1475928660.

- ProQuest 2594621682.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 8.

- ^ "Theatre's Dilemma; 2 Hits Cut Matinees; Miss Goddard's Role". New York Daily News. June 6, 1940. p. 611. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Hartman, Walter (October 21, 1940). "'Sunrise' Strikes Yiddish Theatre As Hit Musical". New York Daily News. p. 108. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Yiddish Cavalcade". New York Daily News. January 2, 1941. p. 236. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1248214943.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "Sarah Churchill Back on the London Stage; Betty Field's Film Role". New York Daily News. February 15, 1941. p. 277. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1261403585.

- ^ "Films for Century". New York Daily News. March 14, 1941. p. 257. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 105571580.

- ProQuest 1263682179.

- ProQuest 1264310095.

- ProQuest 106247408.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ProQuest 1249235099.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ProQuest 1322516155.

- ^ "Getting Married". New York Daily News. October 5, 1953. p. 63. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ProQuest 1017002496.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ProQuest 1843931394.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 9.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ProQuest 1014806771.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, pp. 18–19.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ProQuest 1565192486.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 19.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ Kubasik, Ben (October 6, 1959). "An Off-Broadway Playhouse Casts Itself in Long-Run Role". Newsday. p. 53. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ProQuest 1325840685.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1014844350.

- ProQuest 1326268708.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ Davis, James (March 12, 1962). "The Backstage Beat". New York Daily News. p. 13. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ProQuest 133058401.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ ProQuest 1014850479.

- ^ "A Bust in Burlesque Strike? Anne Howe!". New York Daily News. April 3, 1967. p. 141. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ McHarry, Charles (November 29, 1965). "On the Town". New York Daily News. p. 147. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Seligsohn, Leo (April 18, 1969). "Tynan Planning 'Elegant Erotica'". Newsday (Nassau Edition). p. 143. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ProQuest 133388687.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ProQuest 1014865052.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1993, p. 20.

- ^ a b Davis, James (February 2, 1971). "'La Mancha' Loses Beck to a New Albee Drama". New York Daily News. p. 203. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Silver, Lee (May 13, 1971). "'Man of La Mancha' Moving to Hellinger". New York Daily News. p. 254. Retrieved April 17, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 962906091.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ProQuest 1523638018.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ProQuest 1017176523.

- ^ Wallach, Allan (September 11, 1972). "'Crazy Now' isn't wild, it's only mild as a revue". The Herald Statesman. p. 11. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Lisker, Jerry (October 24, 1972). "Musical 'Yoshe Kalb' A Splendid Production". New York Daily News. p. 39. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Watt, Douglas (May 21, 1973). "'Smith' is a Musical About a Poor Musical". New York Daily News. p. 186. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Popkin, Henry (October 21, 1974). "'Big Winner' is just that". The Herald Statesman. p. 21. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Norkin, Sam (October 22, 1974). "Sholom Aleichem's Return to 2d Ave". New York Daily News. p. 193. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ O'Haire, Patricia (October 17, 1975). "Joe leaps a barrier". New York Daily News. p. 69. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1476136477.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "'Whorehouse' moving uptown". New York Daily News. June 8, 1978. p. 315. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "God Bless You Mr. Rosewater". Lortel Archives. October 14, 1979. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ProQuest 1401338408.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "Federal Register: 51 Fed. Reg. 6497 (Feb. 25, 1986)" (PDF). Library of Congress. February 25, 1986. p. 6654 (PDF p. 158). Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Wallach, Allan (November 12, 1985). "Yiddish evocations of 'Golden Land'". Newsday. p. 146. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Wallach, Allan (October 30, 1986). "Frankenstein With a Song in His Heart". Newsday. p. 200. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Robins, Wayne (March 20, 1987). "The Musical Legend of 'Staggerlee'". Newsday. p. 201. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Watt, Douglas (January 8, 1988). "'The Chosen': A Not-So-Great Choice". New York Daily News. p. 328. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ProQuest 1286176308.

- ^ Passalacqua, Connie (February 8, 1991). "Making Moviegoing Mellow". Newsday. pp. 70, 71. Retrieved April 18, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "Village East Cinema". EverGreene. July 8, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Ramsay, James (March 4, 2021). "With Everything Streaming, Will Moviegoers Return To NYC Theaters For The Love Of The Big Screen?". Gothamist. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Dade (March 5, 2021). "NYC Art House Movie Theaters Awaken After Year Of Hibernation, But One Holds The Popcorn". Deadline. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Sampson, Mike (March 5, 2021). "Less Popcorn, More Distance: How Indie Movie Theaters Are Gingerly Reopening". Curbed. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Jake (November 10, 2021). "Village East Cinema Plans To Expand With New Bar And Kitchen". What Now NY: The Best Source For New York News. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Murphy, J. Kim (March 23, 2023). "Tommy Wiseau Unveils His Follow-Up Film to 'The Room' With 'Big Shark' Trailer (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ "Coriolanus". Lortel Archives. January 19, 1954. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "The Seagull". Lortel Archives. May 11, 1954. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (September 20, 1955). "Marcel Marceau – Broadway Special – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Marcel Marceau (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1955)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (December 11, 1955). "Six Characters in Search of an Author – Broadway Play – 1955 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Six Characters in Search of an Author (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1955)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "The Adding Machine". Lortel Archives. February 9, 1956. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Miss Julie / The Stronger". Lortel Archives. February 21, 1956. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

"Miss Julie and The Stronger (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1956)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (April 3, 1956). "A Month in the Country – Broadway Play – 1956 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"A Month in the Country (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1956)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (September 11, 1956). "Saint Joan – Broadway Play – 1956 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Saint Joan (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1956)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (November 4, 1956). "Diary of a Scoundrel – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Diary of a Scoundrel (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1956)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (December 18, 1956). "The Good Woman of Setzuan – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Good Woman of Setzuan (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1956)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (January 22, 1957). "Measure for Measure – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Measure for Measure (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1957)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (February 20, 1957). "The Taming of the Shrew – Broadway Play – 1957 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Taming of the Shrew (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1957)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (March 19, 1957). "The Duchess of Malfi – Broadway Play – 1957 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Duchess of Malfi (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1957)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (October 8, 1957). "Mary Stuart – Broadway Play – 1957 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Mary Stuart (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1957)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (December 3, 1957). "Makropoulos Secret – Broadway Play – 1957 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Makropoulos Secret (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1957)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (January 9, 1958). "The Chairs and The Lesson – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Chairs and The Lesson (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ^ The Broadway League (February 3, 1958). "The Infernal Machine – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Infernal Machine (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (March 18, 1958). "Two Gentlemen of Verona – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Two Gentlemen of Verona (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ^ The Broadway League (April 1, 1958). "The Broken Jug – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Broken Jug (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ^ The Broadway League (April 29, 1958). "Le Malade Imaginaire – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Le Malade Imaginaire (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (May 6, 1958). "An Evening of 3 Farces – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"An Evening of 3 Farces (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (October 20, 1958). "The Family Reunion – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Family Reunion (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (November 28, 1958). "Britannicus – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Britannicus (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (December 10, 1958). "The Power and the Glory – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Power and the Glory (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (February 24, 1959). "The Beaux Stratagem – Broadway Play – 1959 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Beaux Stratagem (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1959)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (May 11, 1959). "Once Upon a Mattress – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (November 24, 1959). "Lysistrata – Broadway Play – 1959 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Lysistrata (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1959)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (January 12, 1960). "Peer Gynt – Broadway Play – 1960 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Peer Gynt (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1960)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (March 1, 1960). "Henry IV, Part I – Broadway Play – 1960 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"King Henry IV, Part I (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1960)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (April 18, 1960). "Henry IV, Part II – Broadway Play – 1960 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"King Henry IV, Part II (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1960)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (September 7, 1960). "H.M.S. Pinafore – Broadway Musical – 1960 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"H.M.S. Pinafore (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1960)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (November 1, 1960). "She Stoops to Conquer – Broadway Play – 1960 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"She Stoops to Conquer (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1960)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (December 6, 1960). "The Plough and the Stars – Broadway Play – 1960 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Plough and the Stars (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1960)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (January 27, 1961). "The Octoroon – Broadway Play – 1961 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"The Octoroon (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1961)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (March 16, 1961). "Hamlet – Broadway Play – 1961 Revival". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Hamlet (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1961)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (June 17, 1969). "Oh! Calcutta! – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Oh! Calcutta! (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1969)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022. - ^ The Broadway League (February 14, 1972). "Grease – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

"Grease (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1972)". Playbill. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

Sources

- Historic Structures Report: Yiddish Art Theatre (PDF) (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 19, 1985.

- Nahshon, Edna (2016). New York's Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54107-7.

- Yiddish Art Theatre (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 9, 1993.

- Yiddish Art Theatre Interior (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 9, 1993.

External links

- Village East by Angelika website

- Eden Theatre at the Internet Broadway Database

- Eden Theatre at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Village East by Angelika at Cinema Treasures