Virgin soil epidemic

In

When a population has been isolated from a particular pathogen without any contact, individuals in that population have not built up any

Diseases introduced to the Americas by Europeans and Africans include smallpox, yellow fever, measles and malaria as well as new strains of typhus and influenza.[5][6]

Virgin soil epidemics also occurred in other regions. For example, the Roman Empire spread smallpox to new populations in Europe and the Middle East in the 2nd century AD, and the Mongol Empire brought the bubonic plague to Europe and the Middle East in the 14th century.[6]

History of the term

The term was coined by

The concept would later be adopted wholesale by

Historical instances

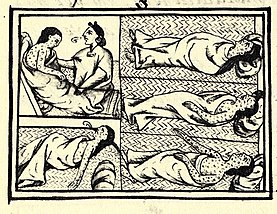

Native American epidemics

Due to limited interaction between communities and more limited instances of

Cocoliztli epidemics

A series of epidemics of unknown origin caused major population collapses in Central America in the 16th century, possibly due to little immunological protection from previous exposures. While the pathogenic agents of these so-called Cocoliztli epidemics are unidentified, suspected pathogenic agents include endemic viral agents, Salmonella, or smallpox.[10][11]

Australian Aboriginal epidemics

The European colonization of Australia led to major epidemics among Australian Aboriginies, primarily due to smallpox, influenzas, tuberculosis, measles, and potentially chickenpox.[12][13][14]

Other instances

With malaria spreading in the Caribbean islands after European-African contact, the immunological resistance of African slaves to malaria in contrast to the immunologically defenseless locals might have contributed to African slave trade.[15]

Novel and rapid-spreading pandemics such as the Spanish flu are occasionally referred to as virgin soil pandemics.[16]

Debate

Research over the last few decades has questioned some aspects of the notion of virgin soil epidemics. David S. Jones has argued that the term "virgin soil" is often used to describe a genetic predisposition to disease infection and that it obscures the more complex social, environmental, and biological factors that can enhance or reduce a population's susceptibility.[8]

Paul Kelton has argued that the slave trade in indigenous people by Europeans exacerbated the spread and virulence of smallpox and that a virgin soil model alone cannot account for the widespread disaster of the epidemic.[17]

The debate, as regards smallpox (Variola major or Variola minor), is sometimes complicated by problems in distinguishing its effects from those of other diseases that could prove fatal to virgin soil populations, most notably chickenpox.[18] Thus, the famous virologist Frank Fenner, who played a major role in the worldwide elimination of smallpox, remarked in 1985,[19] "Retrospective diagnosis of cases or outbreaks of disease in the distant past is always difficult and to some extent speculative."

Cristobal Silva has re-examined accounts by colonists of 17th-century New England epidemics and has interpreted and argued that they were products of particular historical circumstances, rather than universal or genetically inevitable processes.[20][21]

Historian Gregory T. Cushman claims that virgin soil epidemics were not the major cause of deaths due to disease among Pacific Island populations. Rather, diseases like tuberculosis and dysentery were able to take hold in Pacific Island populations that had weakened immune systems because of overworking and exploitation by European colonizers.[22]

Historian Christopher R. Browning writes that "Disease, colonization, and irreversible demographic decline were intertwined and mutually reinforcing" in reference to virgin soil epidemics during the European colonisation of the Americas. He contrasts the rebound of the European population following the Black Death with the lack of such a rebound across most Native American populations, attributing this differing demographic trend to the fact that Europeans were not exploited, enslaved, and massacred in the aftermath of the Black Death like the indigenous inhabitants of the New World were. "Disease as the chief killing agent," he writes, "does not remove settler colonialism from the rubric of genocide".[23]

Following this work, historian Jeffrey Ostler has argued that, in relation to European colonization of the Americas, "virgin soil epidemics did not occur everywhere and ... Native populations did not inevitably crash as a result of contact. Most Indigenous communities were eventually afflicted by a variety of diseases, but in many cases this happened long after Europeans first arrived. When severe epidemics did hit, it was often less because Native bodies lacked immunity than because European colonialism disrupted Native communities and damaged their resources, making them more vulnerable to pathogens."[24]

See also

- Columbian Exchange

- Ecological imperialism

- Influx of disease in the Caribbean

- Seasoning (colonialism)

- Native American disease and epidemics

- Millenarianism in colonial societies

- Cocoliztli epidemics

References

- Footnotes

- ^ PMID 11633588.

- ^ a b Cliff et al, p. 120

- ^ a b Hays, p. 87

- ISBN 9780889772960.

- PMID 11633588

- ^ a b Alchon, p. 80

- ISBN 978-0385121224

- ^ JSTOR 3491697.

- ^ Francis, John M. (2005). Iberia and the Americas culture, politics, and history: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- S2CID 256726167.

- PMID 11971767.

- ^ Dowling, Peter (2021). Fatal contact: How epidemics nearly wiped out Australia's first peoples. Clayton, Victoria: Monash University Publishing. ISBN 9781922464460.

- .

- ^ Dowling, Peter. “‘A Great Deal of Sickness’: Introduced Diseases among the Aboriginal People of Colonial Southeast Australia,” 1997.

- )

- S2CID 20066083.

- ^ Kelton, Paul (2007). Epidemics and Enslavement: Biological Catastrophe in the Native Southeast, 1492-1715. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ There is detailed discussion of the difficulty of making this distinction on one continent at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smallpox_in_Australia#Unresolved_Issues_in_the_Chickenpox_Debate and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smallpox_in_Australia#Smallpox_and_chickenpox:_confused_yet_distinct

- PMID 3883104.

- ^ Silva, Cristobal (2011). Miraculous Plagues: An Epidemiology of Early New England Narrative. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- – via Wiley-Blackwell Journals (Frontier Collection).

- ISBN 9781139047470.

- S2CID 246652960. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Ostler, Jeffrey (2019). Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. Yale University Press. pp. 12–13.

- Bibliography

- Alchon, Suzanne Austin (2003), A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective, ISBN 0-8263-2871-7

- Cliff, Andrew David; Haggett, Peter; Smallman-Raynor, Matthew (2000), Island Epidemics, ISBN 0-19-828895-6

- Hays, J. N. (2005), Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History, ISBN 1-85109-658-2