Virginia

Virginia | |

|---|---|

| Commonwealth of Virginia | |

|

Senate | |

| • Lower house | House of Delegates |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Virginia |

| U.S. senators |

|

Mount Rogers[2]) | 5,729 ft (1,746 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2023) | |

| • Total | 8,715,698[3] |

| • Rank | 12th |

| • Density | 219.3/sq mi (84.7/km2) |

| • Rank | 14th |

| • Median household income | $80,615 |

| • Income rank | 10th |

| Demonym | Virginian |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language |

|

EDT) | |

| USPS abbreviation | VA |

| ISO 3166 code | US-VA |

| Traditional abbreviation | Va. |

| Latitude | 36° 32′ N to 39° 28′ N |

| Longitude | 75° 15′ W to 83° 41′ W |

| Website | virginia |

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia,[a] is a state in the Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The state's capital is Richmond and its most populous city is Virginia Beach, though its most populous subdivision is Fairfax County, part of Northern Virginia, where slightly over a third of Virginia's population of 8.72 million live as of 2023[update].

The Blue Ridge Mountains cross the western and southwestern parts of the state. The state's central region lies predominantly in the Piedmont. Eastern Virginia is part of the Atlantic Plain, and the Middle Peninsula forms the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. The fertile Shenandoah Valley fosters the state's most productive agricultural counties, while the economy in Northern Virginia is driven by technology companies and U.S. federal government agencies, including the U.S. Department of Defense and Central Intelligence Agency. Hampton Roads is also the site of the region's main seaport and Naval Station Norfolk, the world's largest naval base.

Virginia's history begins with

Although the state was under

History

Earliest inhabitants

Nomadic hunters are

In response to threats from these other groups to their trade network, thirty or so

Colony

Several European expeditions, including a

Though more settlers soon joined, many were ill-prepared for the dangers of the new settlement. As the colony's president,

From the colony's start, residents agitated for greater local control, and in 1619, certain male colonists began electing representatives to an assembly, later called the House of Burgesses, that negotiated issues with the governing council appointed by the London Company.[26] Unhappy with this arrangement, the monarchy revoked the company's charter and began directly naming governors and Council members in 1624. In 1635, colonists arrested a governor who ignored the assembly and sent him back to England against his will.[27] William Berkeley was named governor in 1642, just as the turmoil of the English Civil War and Interregnum permitted the colony greater autonomy.[28] As supporter of the king, Berkeley welcomed other so-called Cavaliers who fled to Virginia. He surrendered to Parliamentarians in 1652, but after the 1660 Restoration made him governor again, he blocked assembly elections and exacerbated the class divide by disenfranchising and restricting the movement of indentured servants, who made up around eighty percent of the colony's workforce.[29] On the colony's frontier, Piedmont tribes like the Tutelo and Doeg were being squeezed by Seneca raiders from the north, leading to more confrontations with colonists. In 1676, several hundred working-class followers of Nathaniel Bacon, upset by Berkeley's refusal to retaliate against the tribes, marched to Jamestown and burned it.[30]

Bacon's Rebellion forced the signing of Bacon's Laws, which restored some of the colony's rights and sanctioned both attacks on native tribes and the enslavement of their men and women.[31] The Treaty of 1677 further reduced the independence of the tribes that signed it, and aided the colony's assimilation of their land in the years that followed.[32][33] Colonists in the 1700s were pushing westward into this area held by the Seneca and their larger Iroquois Nation, and in 1748, a group of wealthy speculators, backed by the British monarchy, formed the Ohio Company to start English settlement and trade in the Ohio Country west of the Appalachian Mountains.[34] The Kingdom of France, which claimed this area as part of their colony of New France, viewed this as a threat, and in 1754 the French and Indian War engulfed England, France, the Iroquois, and other allied tribes on both sides. A militia from several British colonies, called the Virginia Regiment, was led by 21-year-old Major George Washington, himself one of the investors in the Ohio Company.[35]

Statehood

In the decade following the

After the

Virginians were instrumental in the new country's early years and in writing the

Civil War

Between 1790 and 1860, the number of

On October 16, 1859, abolitionist

In Virginia,

The armies of the Union and Confederacy first met on July 21, 1861, in Battle of Bull Run near Manassas, Virginia, where a bloody Confederate victory established that the war would not be easily decided. Union General George B. McClellan organized the Army of the Potomac, which landed on the Virginia Peninsula in March 1862 and reached the outskirts of Richmond that June. With Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston wounded in fighting outside the city, command of his Army of Northern Virginia fell to Robert E. Lee. Over the next month, Lee drove the Union army back, and starting that September led the first of several invasions into Union territory. During the next three years of war, more battles were fought in Virginia than anywhere else, including the battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Spotsylvania, and the concluding Battle of Appomattox Court House, where Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865.[57] After the capture of Richmond that month, the state capital was briefly moved to Lynchburg,[58] while the Confederate leadership fled to Danville.[59] 32,751 Virginians died in the Civil War.[60]

Reconstruction and Jim Crow

Virginia was formally restored to the United States in 1870, due to the work of the

The Readjusters focused on building up schools, like

New economic forces would meanwhile industrialize the Commonwealth. Virginian

Civil rights to present

Protests against underfunded segregated schools started by

Federal passage of the Civil Rights Act in June 1964 and Voting Rights Act in August 1965, and their later enforcement by the Justice Department, helped end racial segregation in Virginia and overturn Jim Crow era state laws.[78] In June 1967, the Supreme Court also struck down the state's ban on interracial marriage with Loving v. Virginia. In 1968, Governor Mills Godwin called a commission to rewrite the state constitution. The new constitution, which banned discrimination and removed articles that now violated federal law, passed in a referendum with 71.8% support and went into effect in June 1971.[79] In 1977, Black members became the majority of Richmond's city council; in 1989, Douglas Wilder became the first African American elected as governor in the United States; and in 1992, Bobby Scott became the first Black congressman from Virginia since 1888.[80][81]

The expansion of federal government offices into Northern Virginia's suburbs during the

Geography

Virginia is located in the

Virginia's southern border

Geology and terrain

The Chesapeake Bay separates the contiguous portion of the Commonwealth from the two-county peninsula of Virginia's Eastern Shore. The bay was formed from the drowned river valley of the ancient Susquehanna River.[96] Many of Virginia's rivers flow into the Chesapeake Bay, including the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James, which create three peninsulas in the bay, traditionally referred to as "necks" named Northern Neck, Middle Peninsula, and the Virginia Peninsula from north to south.[97] Sea level rise has eroded the land on Virginia's islands, which include Tangier Island in the bay and Chincoteague, one of 23 barrier islands on the Atlantic coast.[98][99]

The

The

The Commonwealth's carbonate rock is filled with more than 4,000

Climate

| Virginia state-wide averages 1895–2023 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Virginia has a humid subtropical climate that transitions to humid continental west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.[113] Seasonal extremes vary from average lows of 25 °F (−4 °C) in January to average highs of 86 °F (30 °C) in July.[114] The Atlantic Ocean and Gulf Stream have a strong effect on eastern and southeastern coastal areas of the Commonwealth, making the climate there warmer but also more constant. Most of Virginia's recorded extremes in temperature and precipitation have occurred in the Blue Ridge Mountains and areas west.[115] Virginia receives an average of 43.47 inches (110 cm) of precipitation annually,[114] with the Shenandoah Valley being the state's driest region due to the mountains on either side.[115]

Virginia has around 35–45 days with thunderstorms annually, and storms are common in the late afternoon and evenings between April and September.

Part of this is due to climate change in Virginia, which is leading to higher temperatures year-round as well as more heavy rain and flooding events.[124] Urban heat islands can be found in many Virginia cities and suburbs, particularly in neighborhoods linked to historic redlining.[125][126] Fairfax County had the most code orange days in 2022 for high ozone pollution in the air, with five, followed by Arlington with four.[127] The closure and conversion of coal power plants in Virginia and the Ohio Valley region has reduced haze in the mountains, which peaked in 1998.[128] Exposure of particulate matter in Virginia's air has been cut in half from 13.5 micrograms per cubic meter in 2003, when coal provided half of Virginia's electricity, to 6.6 in 2023,[129] when coal provided just 3.3%, less than renewables like solar power and biomass.[130][131] Current plans call for 30% of the Commonwealth's electricity to be renewable by 2030 and for all to be carbon-free by 2050.[132]

Ecosystem

Forests cover 62% of Virginia as of 2021[update], of which 80% is considered

Virginia has 226 species of

Protected lands

As of 2019[update], roughly 16.2% of land in the Commonwealth is protected by federal, state, and local governments and non-profits.[156] Federal lands account for the majority, with thirty National Park Service units in the state, such as Great Falls Park and the Appalachian Trail, and one national park, Shenandoah.[157] Shenandoah was established in 1935 and encompasses the scenic Skyline Drive. Almost forty percent of the park's total 199,173 acres (806 km2) area has been designated as wilderness under the National Wilderness Preservation System.[158] The U.S. Forest Service administers the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, which cover more than 1.6 million acres (6,500 km2) within Virginia's mountains, and continue into West Virginia and Kentucky.[159] The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge also extends into North Carolina, as does the Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, which marks the beginning of the Outer Banks.[160]

State agencies control about one-third of protected land in the state,[156] and the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation manages over 75,900 acres (307.2 km2) in forty Virginia state parks and 59,222 acres (239.7 km2) in 65 Natural Area Preserves, plus three undeveloped parks.[161][162] Breaks Interstate Park crosses the Kentucky border and is one of only two inter-state parks in the United States.[163] Sustainable logging is allowed in 26 state forests managed by the Virginia Department of Forestry totaling 71,972 acres (291.3 km2),[164] as is hunting in 44 Wildlife Management Areas run by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources covering over 205,000 acres (829.6 km2).[165] The Chesapeake Bay is not a national park, but is protected by both state and federal legislation and the inter-state Chesapeake Bay Program, which conducts restoration on the bay and its watershed.[166]

Cities and towns

Virginia is divided into 95

Over three million people, 35% of Virginians, live in the twenty jurisdictions collectively defined as Northern Virginia, which is part of the larger Washington metropolitan area and the Northeast megalopolis.[172][173] Fairfax County, with more than 1.1 million residents, is Virginia's most populous jurisdiction,[174] and has a major urban business and shopping center in Tysons, Virginia's largest office market.[175] Neighboring Prince William County is Virginia's second most populous county, with a population exceeding 450,000, and is home to Marine Corps Base Quantico, the FBI Academy and Manassas National Battlefield Park. Loudoun County, with its county seat at Leesburg, is the fastest-growing county in the state.[174][176] Arlington County is the smallest self-governing county in the U.S. by land area,[177] and local politicians have proposed reorganizing it as an independent city due to its high density.[170]

Richmond is the capital of Virginia, and its city proper has a population of over 230,000, while its metropolitan area has over 1.3 million.[172] As of 2021[update], Virginia Beach is the most populous independent city in the Commonwealth, with Chesapeake and Norfolk second and third, respectively.[178] The three are part of the larger Hampton Roads metropolitan area, which has a population over 1.7 million people and is the site of the world's largest naval base, Naval Station Norfolk.[172][179] Suffolk, which includes a portion of the Great Dismal Swamp, is the largest city by area at 429.1 square miles (1,111 km2).[180] In western Virginia, Roanoke city and Montgomery County, part of the Blacksburg–Christiansburg metropolitan area, both have surpassed a population of over 100,000 since 2018.[181]

Largest Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas in Virginia

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name

|

Pop. | Rank | Name

|

Pop. | ||||

Northern Virginia  Hampton Roads |

1 | Northern Virginia | 3,061,478 | 11 | Danville | 102,187 |  Richmond  Roanoke | ||

| 2 | Hampton Roads | 1,726,251 | 12 | Bristol |

92,108 | ||||

| 3 | Richmond | 1,324,062 | 13 | Martinsville | 63,765 | ||||

| 4 | Roanoke | 314,496 | 14 | Tazewell | 39,925 | ||||

| 5 | Lynchburg | 262,258 | 15 | Big Stone Gap | 39,313 | ||||

| 6 | Charlottesville | 222,688 | |||||||

| 7 | Blacksburg–Christiansburg | 165,293 | |||||||

| 8 | Harrisonburg | 135,824 | |||||||

| 9 | Staunton–Waynesboro | 125,774 | |||||||

| 10 | Winchester | 145,155 | |||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 691,737 | — | |

| 1800 | 807,557 | 16.7% | |

| 1810 | 877,683 | 8.7% | |

| 1820 | 938,261 | 6.9% | |

| 1830 | 1,044,054 | 11.3% | |

| 1840 | 1,025,227 | −1.8% | |

| 1850 | 1,119,348 | 9.2% | |

| 1860 | 1,219,630 | 9.0% | |

| 1870 | 1,225,163 | 0.5% | |

| 1880 | 1,512,565 | 23.5% | |

| 1890 | 1,655,980 | 9.5% | |

| 1900 | 1,854,184 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 2,061,612 | 11.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,309,187 | 12.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,421,851 | 4.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,677,773 | 10.6% | |

| 1950 | 3,318,680 | 23.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,966,949 | 19.5% | |

| 1970 | 4,648,494 | 17.2% | |

| 1980 | 5,346,818 | 15.0% | |

| 1990 | 6,187,358 | 15.7% | |

| 2000 | 7,078,515 | 14.4% | |

| 2010 | 8,001,024 | 13.0% | |

| 2020 | 8,631,393 | 7.9% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 8,715,698 | 1.0% | |

| 1790–2020,[182][183] 2023[3] | |||

The

Though still growing naturally as births outnumber deaths, Virginia has had a negative net migration rate since 2013, with 8,995 more people leaving the state than moving to it in 2021. This is largely credited to high home prices in Northern Virginia,[187] which are driving residents there to relocate south, and although Raleigh is their top destination, in-state migration from Northern Virginia to Richmond increased by 36% in 2020 and 2021 compared to the annual average over the previous decade.[188][189] Aside from Virginia, the top birth state for Virginians is New York, having overtaken North Carolina in the 1990s, with the Northeast accounting for the largest number of domestic migrants into the state by region.[190] About twelve percent of residents were born outside the United States as of 2020[update]. El Salvador is the most common foreign country of birth, with India, Mexico, South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam as other common birthplaces.[191]

Race and ethnicity

The state's most populous racial group,

The largest minority group in Virginia are Blacks and African Americans, who include about one-fifth of the population.

More recent immigration in the late 20th century and early 21st century has resulted in new communities of Hispanics and Asians. As of 2020[update], 10.5% of Virginia's total population describe themselves as

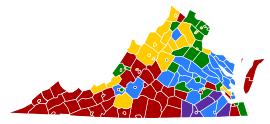

| Largest race by county or city | Race and ethnicity (2020) | Alone | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Non-Hispanic White | 58.6% | 62.8% | |||

| Black or African American | 18.3% | 20.1% | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 10.5% | |||||

| Asian | 7.1% | 8.6% | ||||

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.2% | 1.5% | ||||

| Other | 0.6% | 1.5% | ||||

| Largest ancestry by county or city | Ancestry (2020 est.) | Total | ||||

|

|

Irish or Scotch-Irish

|

10.4% | ||||

German

|

10.3% | |||||

English

|

9.8% | |||||

American

|

9.4% | |||||

Subsaharan African

|

2.3% | |||||

Languages

According to U.S. Census data as of 2019[update] on Virginia residents aged five and older, 83.2% (6,683,027) speak

English was passed as the Commonwealth's official language by statutes in 1981 and again in 1996, though the status is not mandated by the

Religion

Virginia is predominantly

The

In November 2006, fifteen conservative Episcopal churches voted to split from the Diocese of Virginia over the ordination of openly

Among other religions, adherents of

Economy

Virginia's economy has diverse sources of income, including local and federal government, military, farming and high-tech. The state's average per capita income in 2022 was $68,211,[234] and the gross domestic product (GDP) was $654.5 billion, both ranking as 13th-highest among U.S. states.[235] The COVID-19 recession caused jobless claims due to soar over 10% in early April 2020,[236] before leaving off around 5% in November 2020 and returning to pre-pandemic levels in 2023.[237] In March 2024, the unemployment rate was 2.9%, which was the 11th-lowest nationwide.[238]

Virginia had a

Virginia's business environment has been ranked highly by various publications. After two years as number one,

Government agencies

Government agencies directly employ around 714,100 Virginians as of 2022[update], almost 17% of all employees in the state.

Other large

Business

Based on data as of 2020[update], Virginia is home to 204,131 separate employers plus 644,341

Virginia has the third highest concentration of technology workers and the fifth highest overall number among U.S. states as of 2020[update], with the 451,268 tech jobs accounting for 11.1% of all jobs in the state and earning a median salary of $98,292.

Northern Virginia became the world's largest

Tourism in Virginia supported an estimated 185,000 jobs in 2021,[272] making tourism the state's fifth-largest industry. It generated $26 billion in 2018, an increase of 4.4% from the previous year.[273] The state was eighth nationwide in domestic travel spending in 2018, with Arlington County the top tourist destination in the state by domestic spending, followed by Fairfax County, Loudoun County, and Virginia Beach.[274] Virginia also saw 1.1 million international tourists in 2018, a five percent increase from 2017.[275]

Agriculture

As of 2021[update], agriculture occupies 30% of the land in Virginia with 7.7 million acres (12,031 sq mi; 31,161 km2) of farmland. Nearly 54,000 Virginians work on the state's 41,500 farms, which average 186 acres (0.29 sq mi; 0.75 km2). Though agriculture has declined significantly since 1960 when there were twice as many farms, it remains the largest industry in Virginia, providing for over 490,000 jobs.[277] Soybeans were the most profitable single crop in Virginia in 2022[278] although the ongoing trade war with China has led many Virginia farmers to plant cotton instead of soybeans.[279] Other leading agricultural products include corn, cut flower and tobacco, where the state ranks third nationally in the production of the crop.[277][278]

Virginia is the country's third-largest producer of seafood as of 2021[update], with sea scallops, oysters, Chesapeake blue crabs, menhaden, and hardshell clams as the largest seafood harvests by value, and France, Canada, New Zealand, and Hong Kong as the top export destinations.[280] Commercial fishing supports 18,220 jobs as of 2020[update], while recreation fishing supports another 5,893.[281] The population of eastern oysters collapsed in the 1980s due to pollution and overharvesting, but has slowly rebounded, and the 2022–2023 season saw the largest harvest in 35 years with around 700,000 US bushels (25,000 kL).[282] A warm winter and a dry summer made the 2023 wine harvest one of the best for vineyards in the Northern Neck and along the Blue Ridge Mountains, which also attract 2.6 million tourists annually.[283][284] Virginia has the seventh-highest number of wineries in the nation, with 388 producing 1.1 million cases a year as of 2024[update].[285] Cabernet Franc and Chardonnay are the most grown varieties.[286] Breweries in Virginia also produced 460,315 barrels (54,017 kl) of craft beer in 2022, the 15th-most nationally.[287]

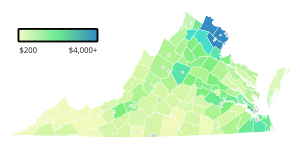

Taxes

Virginia's property tax is set and collected at the local government level and varies throughout the Commonwealth. Real estate is also taxed at the local level based on one hundred percent of fair market value.[293] As of 2021[update], the overall median real estate tax rate per $100 of assessed taxable value was $0.96, though for 72 of the 95 counties this number was under $0.80 per $100. Northern Virginia has the highest property taxes in the state, with Manassas Park paying the highest effective tax rate at $1.31 per $100, while Powhatan and Lunenburg counties were tied for the lowest, at $0.30.[294] Of local government tax revenue, about 61% is generated from real property taxes while 24% is from tangible personal property, sales and use, and business license tax. The remaining 15% come from taxes on hotels, restaurant meals, public service corporation property, and consumer utilities.[295]

Culture

Modern Virginian culture has many sources and is part of the culture of the Southern United States.[296] The Smithsonian Institution divides Virginia into nine cultural regions, and in 2007 used their annual Folklife Festival to recognize the substantial contributions of England and Senegal on Virginian culture.[297] Virginia's culture was popularized and spread across America and the South by figures such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Robert E. Lee. Their homes in Virginia represent the birthplace of America and the South.[298]

Besides the general cuisine of the Southern United States, Virginians maintain their own particular traditions. Virginia wine is made in many parts of the Commonwealth.[284] Smithfield ham, sometimes called "Virginia ham", is a type of country ham which is protected by state law and can be produced only in the town of Smithfield.[299] Virginia furniture and architecture are typical of American colonial architecture. Thomas Jefferson and many of the Commonwealth's early leaders favored the Neoclassical architecture style, leading to its use for important state buildings. The Pennsylvania Dutch and their style can also be found in parts of the Commonwealth.[198]

Literature in Virginia often deals with the Commonwealth's extensive and sometimes troubled past. The works of

Fine and performing arts

Virginia ranks near the middle of U.S. states in terms of public spending on the arts as of 2021[update], at just over half of the national average.

Theaters and venues in Virginia are found both in the cities and in suburbs. The

Virginia is known for its tradition in the music genres of

Festivals

Many counties and localities host

The Shenandoah Apple Blossom Festival is a two-week festival held annually in Winchester which includes parades and bluegrass concerts. The Old Time Fiddlers' Convention in Galax, begun in 1935, is one of the oldest and largest such events worldwide, and Wolf Trap hosts the Wolf Trap Opera Company, which produces an opera festival every summer.[314] The Blue Ridge Rock Festival has operated since 2017, and has brought as many as 33,000 concert-goers to the Blue Ridge Amphitheater in Pittsylvania County.[323] Two important film festivals, the Virginia Film Festival and the VCU French Film Festival, are held annually in Charlottesville and Richmond, respectively.[324]

Law and government

In 1619, the first

Virginia's legislature is

State budgets are biennial and are proposed by the governor in even years.[330] Based on data through 2018, the Pew Center on the States found Virginia's government to be above average in running surpluses,[331] and U.S. News & World Report ranked the state tenth in fiscal stability.[332] The legislature starts regular sessions on the second Wednesday of every year, which meet for up to 48 days in odd years and 60 days in even years to allow more time for the state budget.[328] After regular sessions end, special sessions can be called either by the governor or with agreement of two-thirds of both houses, and twenty special sessions have been called since 2000, typically for legislation on preselected issues.[333] Though not a full-time legislature, the Assembly is classified as a hybrid because special sessions are not limited by the state constitution and often last several months.[334] A one-day "veto session" is also automatically triggered when a governor chooses to veto or return legislation to the Assembly with amendments. Vetoes can then be overturned with approval of two-thirds of both the House and Senate.[335] A bill that passes with two-thirds approval can also become law without action from the governor,[336] and Virginia has no "pocket veto", so bills become law if the governor chooses to neither approve nor veto them.[337]

Legal system

The judges and justices who make up

The Code of Virginia is the statutory law and consists of the codified legislation of the General Assembly. The largest law enforcement agency in Virginia is the Virginia State Police, with 3,035 sworn and civilian members as of 2019[update].[342] The Virginia Marine Police patrol coastal areas, and were founded as the "Oyster Navy" in 1864 in response to oyster bed poaching.[343] The Virginia Capitol Police protect the legislature and executive department, and are the oldest police department in the United States, dating to the guards who protected the colonial leadership.[344] The governor can also call upon the Virginia National Guard, which consists of approximately 7,200 army soldiers, 1,200 airmen, 300 Defense Force members, and 400 civilians.[345]

Between 1608 and 2021, when the

Politics

Over the past century, Virginia has shifted politically from being a largely rural, conservative,

Enforcement of federal civil rights legislation passed in the mid-1960s helped overturn the state's Jim Crow laws that effectively disfranchised African Americans.[362] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 made Virginia one of nine states that were required to receive federal approval for changes to voting laws, until the system for including states was struck down in 2013.[363] A strict photo identification requirement, added under Governor Bob McDonnell in 2014, was repealed in 2020,[364] and the Voting Rights Act of Virginia was passed in 2021, requiring preclearance from the state Attorney General for local election changes that could result in disenfranchisement, including closing or moving polling sites.[365] Though many Jim Crow provisions were removed in Virginia's 1971 constitution, a lifetime ban on voting for felony convictions was unchanged, and by 2016, up to twenty percent of African Americans in Virginia were disenfranchised because of prior felonies.[366] That year, Governor Terry McAuliffe ended the lifetime ban and individually restored voting rights to over 200,000 ex-felons.[359] These changes moved Virginia from being ranked as the second most difficult state to vote in 2016, to the twelfth easiest in 2020.[367]

Regional differences also play a large part in Virginia politics. While urban and expanding suburban areas, including much of

State elections

Republican gain Democratic gain

State elections in Virginia occur in odd-numbered years, with executive department elections occurring in years following U.S. presidential elections and

The

In 2021, Glenn Youngkin became the first Republican to win the governor's race since 2009,[387] with his party also winning the races for lieutenant governor and attorney general and gaining seven seats in the House of Delegates.[388][389] Two years later, new legislative maps drawn by special masters appointed by the state supreme court led to nine retirements in the state senate and to twenty-five House delegates not seeking re-election. In those elections, Democrats claimed a slim majority of one seat in both the Senate and the House.[390]

Federal elections

Though Virginia was considered a "

Education

Virginia's educational system consistently ranks in the top five states on the U.S. Department of Education's National Assessment of Educational Progress, with Virginia students outperforming the average in all subject areas and grade levels tested.[398] The 2021 Quality Counts report ranked Virginia's K–12 education thirteenth in the country, with a letter grade of B−.[399] Virginia's K–7 schools had a student–teacher ratio of 12.15:1 as of the 2021–22 school year, and 12.52:1 for grades 8–12.[400] All school divisions must adhere to educational standards set forth by the Virginia Department of Education, which maintains an assessment and accreditation regime known as the Standards of Learning to ensure accountability.[401]

Public

In 2022, 92.1% of high school students graduated on-time after four years,[407] and 89.3% of adults over the age 25 had their high school diploma.[3] Virginia has one of the smaller racial gaps in graduation rates among U.S. states,[408] with 90.3% of Black students graduating on time, compared to 94.9% of white students and 98.3% of Asian students. Hispanic students had the highest dropout rate, at 13.95%, with high rates being correlated with students listed as English learners.[407] Despite ending school segregation in the 1960s, seven percent of Virginia's public schools were rated as "intensely segregated" by The Civil Rights Project at UCLA in 2019, and the number has risen since 1989, when only three percent were.[409] Virginia has comparatively large public school districts, typically comprising entire counties or cities, and this helps mitigate funding gaps seen in other states such that non-white districts average slightly more funding, $255 per student as of 2019[update], than majority white districts.[410] Elementary schools, with Virginia's smallest districts, were found to be more segregated than state middle or high schools by a 2019 VCU study.[411]

Colleges and universities

As of 2020[update], Virginia has the

Virginia Tech and Virginia State University are the state's land-grant universities, and Virginia State is one of five historically black colleges and universities in Virginia.[416] The Virginia Military Institute is the oldest state military college.[417] Virginia also operates 23 community colleges on 40 campuses which enrolled 218,985 degree-seeking students during the 2020–2021 school year.[418] In 2021, the state made community college free for most low- and middle-income students.[419] George Mason University had the largest on-campus enrollment at 38,542 students as of 2021[update],[420] though the private Liberty University had the largest total enrollment in the state, with 88,283 online and 15,105 on-campus students in Lynchburg as of 2019[update].[421]

Health

Virginia has a mixed health record. The state was ranked best for its physical environment in the 2023 United Health Foundation's Health Rankings, but 19th for its overall health outcomes and only 26th for residents healthy behaviors. Among U.S. states, Virginia has the 22nd lowest rate of premature deaths, with 8,709 per 100,000,[129] and an infant mortality rate of 5.61 per 1,000 live births.[423] The rate of uninsured Virginians dropped to 6.5% in 2023, following an expansion of Medicare in 2019.[129] Falls Church and Loudoun County were both ranked in the top ten healthiest communities in 2020 by U.S. News & World Report.[424]

There are however racial and social health disparities. With high rates of heart disease and diabetes, African Americans in Virginia have an average life expectancy four years less than whites and twelve less than Asian Americans and Latinos,[425] and were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 during the coronavirus pandemic.[426] African-American mothers are also three times more likely to die while giving birth in the state.[427] Mortality rates among white middle-class Virginians have also been rising, with drug overdose, alcohol poisoning, and suicide as leading causes.[428] Suicides in the state increased over 14% between 2009 and 2023, while deaths from drug overdoses more than doubled in that time.[129] Virginia has a ratio of 221.5 primary care physicians per 10,000 residents, the fifteenth worst rate nationally, and only 250.3 mental health providers per that number, the fourteenth worst nationwide.[129] A December 2023 report by the General Assembly found that all nine public mental health care facilities were over 95% full, causing overcrowding and delays in admissions.[429]

Weight is an issue for many Virginians, and 32.2% of adults and 14.9% of 10- to 17-year-olds are obese as of 2021[update].

The

Media

The

There are 36

The most circulated

Transportation

Because of the 1932 Byrd Road Act, the state government controls most of Virginia's roads, instead of a local county authority as is usual in other states.[449] As of 2018[update], the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) owns and operates 57,867 miles (93,128 km) of the total 70,105 miles (112,823 km) of roads in the state, making it the third-largest state highway system in the nation.[450]

Traffic on Virginia's roads is among the worst in the nation according to the 2019 American Community Survey. The average commute time of 28.7 minutes is the eighth-longest among U.S. states, and the Washington Metropolitan Area, which includes Northern Virginia, has the second-worst rate of traffic congestion among U.S. cities.[451] About 67.9% of workers in Virginia reported driving alone to work in 2021, the foureenth lowest percent in the U.S.,[129] while 8.5% reported carpooling,[452] and Virginia hit peak car usage before the year 2000, making it one of the first such states.[453]

Mass transit and ports

About 3.4% of Virginians commute on public transit,

Virginia has

Virginia has five major airports: Dulles International and Reagan Washington National in Northern Virginia, both of which handle over 20 million passengers a year, Richmond International southeast of the state capital, Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport, and Norfolk International. Several other airports offer limited commercial passenger service, and sixty-six public airports serve the state's aviation needs.[462] The Virginia Port Authority's main seaports are those in Hampton Roads, which carried 61,505,700 short tons (55,797,000 t) of total cargo in 2021[update], the sixth most of United States ports.[463] The Eastern Shore of Virginia is the site of Wallops Flight Facility, a rocket launch center owned by NASA, and the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport, a commercial spaceport.[464][465] Space tourism is also offered through Vienna-based Space Adventures.[466]

Sports

Virginia is the most populous U.S. state without a

Five

Among individual athletes,

College sports

In the absence of professional sports, several of Virginia's collegiate sports programs have attracted strong followings, with a 2015 poll showing that 34% of Virginians were fans of the

High school sports

Virginia is also home to several of the nation's top high school

State symbols

Virginia has several nicknames, the oldest of which is the "Old Dominion". King

The state's motto, Sic Semper Tyrannis, translates from Latin as "Thus Always to Tyrants", and is used on the state seal, which is then used on the flag.[1] While the seal was designed in 1776, and the flag was first used in the 1830s, both were made official in 1930.[495] The majority of the other symbols were made official in the late 20th century.[496] In 1940, "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny" was named the state song, but it was retired in 1997 due to its nostalgic references to slavery. In March 2015, Virginia's government named "Our Great Virginia", which uses the tune of "Oh Shenandoah", as the traditional state song and "Sweet Virginia Breeze" as the popular state song.[497]

- Beverages: Milk, Rye Whiskey

- Boat: Chesapeake Bay deadrise

- Bird: Cardinal

- Dance: Square dancing

- Dog: American Foxhound

- Fish: Brook trout, striped bass

- Tree: Dogwood

- Fossil: Chesapecten jeffersonius

- Insect: Tiger swallowtail

- Mammal: Virginia big-eared bat

- Motto: Sic Semper Tyrannis

- Nickname: The Old Dominion

- Chincoteague Pony

- Shell: Eastern oyster

- Slogan: Virginia is for Lovers

- Songs: "Our Great Virginia", "Sweet Virginia Breeze"

- Tartan: Virginia Quadricentennial

See also

Notes

- ^ Virginia is one of only four U.S. states to use the term "Commonwealth" in its official name, along with Massachusetts, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.

References

- ^ a b Hamilton 2016, pp. 6

- ^ a b Burnham & Burnham 2018, pp. 277

- ^ a b c d e f g h "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Laurie Gwen (June 22, 2014). "Pocahontas: Fantasy and Reality". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on June 23, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Egloff & Woodward 2006, pp. 2–14.

- ^ Egloff & Woodward 2006, pp. 5, 31–39.

- ^ a b Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 4–11

- ^ Stebbins, Sarah J. (August 20, 2020). "Chronology of Powhatan Indian Activity". National Park Service. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ "1700: Virginia Native peoples succumb to smallpox". National Institutes of Health. July 10, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- . Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Basnight, Myra (June 7, 2022). "Virginia Treasures: Pocahontas—Her Real World Versus the Legend". AARP. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Glanville, Jim (2009). "16th Century Spanish Invasions of Southwest Virginia" (PDF). Historical Society of Western Virginia Journal (Reprint). XVII (1): 34–42. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Wallenstein 2007, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Moran 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Stewart 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Hulette, Elisabeth (March 19, 2012). "What's in a name?". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Vollmann 2002, pp. 695–696.

- ^ Conlin 2009, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Hoffer 2006, p. 132; Grizzard & Smith 2007, pp. 128–133

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 30.

- ^ Wallenstein 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Hashaw 2007, pp. 76–77, 239–240.

- ^ Eschner, Kat (March 8, 2017). "The Horrible Fate of John Casor, The First Black Man to be Declared Slave for Life in America". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Hashaw 2007, pp. 211–215.

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Gordon 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 32, 37.

- ISBN 978-0-88490-202-7.

- ^ Tarter 2020, pp. 62.

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 51–59.

- ^ Tarter 2020, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 57.

- ^ Shefveland 2016, pp. 59–62.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 23.

- ^ Anderson 2000, pp. 42–43.

- ^ "Signers of the Declaration (Richard Henry Lee)". National Park Service. April 13, 2006. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ Gutzman 2007, pp. 24–29.

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 125–133.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Stephan A. (May 2000). "George Mason: Forgotten Founder, He Conceived the Bill of Rights". Smithsonian. 31 (2): 142.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (November 15, 2010). "Articles of Confederation adopted, Nov. 15, 1777". Politico. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Cooper 2007, p. 58.

- ^ Ketchum 2014, pp. 155.

- ^ Ketchum 2014, pp. 126–131, 137–139, 296.

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 131–133.

- ^ Wallenstein 2007, p. 104.

- ^ a b Robertson 1993, pp. 8–12

- ^ Nesbit, Scott; Nelson, Robert K.; McInnis, Maurie (November 2010). "Visualizing the Richmond Slave Trade". San Antonio: American Studies Association. Retrieved August 30, 2022.

- ^ MacKay, Kathryn L. (May 14, 2006). "Statistics on Slavery". Weber State University. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Morgan 1998, p. 490.

- ^ a b Fischer & Kelly 2000, pp. 202–208

- ^ Bryson 2011, pp. 466–467.

- ^ Jordan 1995, pp. 119–122.

- ^ Davis 2006, pp. 125, 208–210.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (Spring 2011). "John Brown: America's First Terrorist?". Prologue Magazine. Vol. 43, no. 1. U.S. National Archives. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ Jaffa 2000, pp. 230–236, 357–358.

- ^ Carroll, Greg (June 22, 2011). "West (by secession!) Virginia: The Wheeling Conventions, legal vs. illegal separation". The Free Lance-Star. Associated Press. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ Goodwin 2012, pp. 4.

- ^ Smith, Samantha (May 5, 2021). "7 things you probably didn't know about the City of Seven Hills, a.k.a Lynchburg". WSLS NBC10. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Robertson 1993, p. 170.

- ^ "Honoring Virginia's fallen warriors". The Free Lance-Star. May 25, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Erickson, Mark St. John (July 29, 2017). "On this day in 1917, a giant WWI port of embarkation began to transform Hampton Roads". Virginia Daily Press. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 249–250.

- JSTOR 4249314. Retrieved May 21, 2021 – via JStor.

- ^ Davis 2006, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Morgan 1992, pp. 160–166.

- ^ Dailey, Gilmore & Simon 2000, pp. 90–96.

- ISBN 978-0-8139-3876-9.

- JSTOR 2211650. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Dailey, Gilmore & Simon 2000, pp. 99–103.

- ^ Wallenstein 2007, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Styron 2011, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Feuer 1999, pp. 50–52.

- ^ "Editorial: Remembering the Red Summer of 1919". The Roanoke Times. July 21, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- JSTOR 4249293.

- ^ Jones, Mark (February 2, 2013). "It Happened Here First: Arlington Students Integrate Virginia Schools". WETA. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Smith-Richardson, Susan; Burke, Lauren (November 27, 2021). "In the 1950s, rather than integrate its public schools, Virginia closed them". The Guardian. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Wallenstein 2007, pp. 340–341, 350–357.

- ^ Williams, Michael Paul (June 28, 2014). "Civil rights progress in Va., but barriers remain". The Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Adams, Mason (June 30, 2021). "Virginia's latest constitution turns 50". Virginia Business. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Heinemann et al. 2007, pp. 359–366.

- ^ "Voting Rights". Virginia Museum of History & Culture. 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Accordino 2000, pp. 76–78.

- ^ "Three Things About the CIA's Langley Headquarters". Ghosts of D.C. October 2, 2013. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Caplan, David (March 31, 2017). "FBI re-releases 9/11 Pentagon photos". ABC News. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Friedenberger, Amy (April 10, 2020). "Northam signs history-making batch of gun control bills". The Roanoke Times. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Schneider, Gregory S.; Vozzella, Laura (July 7, 2020). "Gen. Robert E. Lee is the only Confederate icon still standing on a Richmond avenue forever changed". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ "Mid-Atlantic Home : Mid–Atlantic Information Office : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". www.bls.gov. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ "United States Regions". National Geographic Society. January 3, 2012. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population and Housing" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2004. p. 71. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ "Supreme Court Rules for Virginia in Potomac Conflict". The Sea Grant Law Center. University of Mississippi. 2003. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- ^ Hampton, Jeff (August 9, 2019). "Along North Carolina-Virginia border, a tiny turn in the map and a history of lies and controversy". The Virginian Pilot. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Van Zandt 1976, pp. 92–95.

- ^ Smith 2015, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Mathews, Dalena; Sorrell, Robert (October 6, 2018). "Pieces of the Past: Supreme Court looked at controversy over Bristol border location". Bristol Herald Courier. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ Noll, David (October 29, 2007). "Great Falls National Park on the Potomac River". Earth Science Picture of the Day. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "Geological Formation". National Park Service. August 8, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Burnham & Burnham 2018, pp. 1.

- ^ Kormann, Carolyn (June 8, 2018). "Tangier, the Sinking Island in the Chesapeake". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ White, Amy Brecount (April 16, 2020). "Shifting sands: Virginia's barrier islands are constantly on the move". Roadtrippers. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ Pazzaglia 2006, pp. 135–138.

- ^ "Virginia's Agricultural Resources". Natural Resource Education Guide. Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. January 21, 2008. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- College of William and Mary. July 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Palmer 1998, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Frost, Peter (August 23, 2011). "Virginia earthquake largest recorded in commonwealth". The Daily Press. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (August 23, 2012). "2011 Virginia earthquake felt by third of U.S." CBS News. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Mayell, Hillary (November 13, 2001). "Chesapeake Bay Crater Offers Clues to Ancient Cataclysm". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Harper, Scott (April 8, 2009). "Lake Drummond's Name and Origin Still a Mystery to Some". The Virginian-Pilot Daily Press. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ Leatherman, Dale (October 12, 2017). "6 Spectacular Caves You'll Want to Explore in the Shenandoah". Washingtonian Magazine. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-57427-110-2. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "Coal" (PDF). Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy. July 31, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ "Comparison of Annually Reported Tonnage Data". Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy. April 7, 2021. Archived from the original (XLS) on July 5, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Vogelsong, Sarah (September 30, 2021). "Uranium mining ban upheld as Supreme Court of Va. declines to reopen lower court ruling". The Virginia Mercury. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ Hamilton 2016, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b U.S. Climate Divisional Dataset (January 2024). "Climate at a Glance". NOAA National Centers for Environmental information. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Burnham & Burnham 2018, pp. xvii–xxi, 64

- ^ Dresbach, Jim (April 11, 2019). "Severe weather awareness for spring, summer". Pentagram. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Annual tornado drill in Virginia will be held March 17". WSET-TV. Associated Press. February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Annual Severe Weather Report Summary". NOAA / National Weather Service. December 31, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Halverson, Jeff (August 19, 2019). "Virginia's deadliest natural disaster unfolded 50 years ago from Hurricane Camille". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Halverson, Jeff (February 7, 2018). "Your primer to understanding Mid-Atlantic cold air damming and 'the wedge'". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Leayman, Emily (January 22, 2020). "Snowiest Day On Record: The Day Fairfax Co. Saw 25.5 Inches Fall". Patch. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Winter Snowfall Departure from Average". NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. March 2022. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Sublette, Sean (March 1, 2023). "We give our Virginia winter forecast a B". The Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Watts, Brent (July 6, 2016). "Virginia summers getting more hot and humid". WDBJ-TV. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Vogelsong, Sarah (January 15, 2020). "In Virginia and U.S., urban heat islands and past redlining practices may be linked, study finds". The Virginia Mercury. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Plumer, Brad; Popovich, Nadja (August 24, 2020). "How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ "Report Card: Virginia". State of the Air: 2022. American Lung Association. April 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ Myatt, Kevin (August 27, 2019). "Weather Journal: You really can see more clearly on hot summer days than you used to". The Roanoke Star. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Virginia" (PDF). America's Health Rankings. United Health Foundation. November 28, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ McGowan, Elizabeth (December 16, 2020). "Report: Dominion Energy must start planning now for coal plant transition". Energy News Network. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Electricity Data Browser, Net generation for all sectors, Virginia, Fuel Type-Check all, Annual, 2001–21". www.eia.gov. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ O'Keefe, Jimmy (October 4, 2019). "Virginia to develop 4 new solar energy projects". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 22, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-4930-1685-3.

- ^ a b Farrell, Rob (2022). "State of the Forest Annual Report on Virginia's Forests – 2021". Virginia Department of Forestry. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Ward, Justin (August 17, 2016). "Gyspy Moths on wide, destructive path in Southwest Virginia". WDBJ-TV. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Common Native Trees of Virginia" (PDF). Virginia Department of Forestry. April 30, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "Wildflowers of Northern Virginia". Prince William Conservation Alliance. May 5, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ Clarkson, Tee (March 3, 2018). "Clarkson: Deer populations abound, but number of hunters continues to decline". The Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c Pagels, John F. (2013). "Virginia Master Naturalist Basic Training Course" (PDF). Virginia Tech. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 31, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "American Black Bear". Shenandoah National Park. August 21, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ "Wildlife Information". Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. June 2, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ University of Florida (December 17, 2009). "Ancient origins of modern opossum revealed". Science Daily. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- .

- ^ a b Karen Terwilliger, A Guide to Endangered and Threatened Species in Virginia (Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries/McDonald & Woodward: 1995), p. 158.

- ^ White, Mel (April 28, 2016). "Birding in Virginia". National Audubon Society. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "Important Bird Areas: Virginia". National Audubon Society. 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Funk, William H. (October 8, 2017). "Peregrine falcons slow to return to Appalachia". The Chesapeake Bay Journal. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ISBN 9781421433073.

- ^ Tkacik, Christina; Dance, Scott (June 10, 2019). "As blue catfish multiply in Chesapeake Bay, watermen pursue new catch". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ Williams, John Page (March 26, 2019). "Spring Feeding". Chesapeake Bay Magazine. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Hedgpeth, Dana (May 25, 2022). "Blue crab population in Chesapeake Bay hits record low". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Bzdyk, Emily (July 1, 2016). "Crayfish". Loudoun Wildlife. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ Jeffrey C. Beane, Alvin L. Braswell, William M. Palmer, Joseph C. Mitchell & Julian R. Harrison III, Amphibians and Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia (2d ed.: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), pp. 51, 102.

- ^ Springston, Rex (May 3, 2019). "Snakes in Virginia: Meet 6 you'll most likely see this season". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Quine, Katie (November 2, 2015). "Why Are the Blue Ridge Mountains Blue?". Our State. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "Virginia's Protected Lands". Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Virginia". National Park Service. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Carroll & Miller 2002, p. 158.

- ^ "The George Washington and Jefferson National Forests". United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service. 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 152–153, 356.

- ^ "Fun Facts". Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ "Virginia Natural Area Preserves". Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. November 20, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Randall (January 12, 2018). "That's the Breaks: Documentary chronicles significant natural area on Virginia-Kentucky border". Knoxville News Sentinel.

- ^ "About the Virginia Department of Forestry". 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Perrotte, Ken (May 23, 2019). "Virginia's Newest Wildlife Management Areas are Shining Examples of How/Where to Buy". Outdoors Rambler. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ "Enactment of Historic Legislation is Major Victory for Chesapeake Bay". Chesapeake Bay Foundation (Press release). October 30, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Virginia Basic Information". United States Census Bureau. June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Library of Virginia 1994, pp. 183.

- ^ Niemeier, Bernie (September 28, 2009). "Unique structural issues make progress in Virginia difficult". Virginia Business. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Austermuhle, Martin (July 14, 2017). "No Longer A County Boy: Arlington Official Says County Should Become A City". WAMU 88.5. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (December 10, 2019). "Virginia Democrats poised to relax Dillon Rule". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020–2021". U.S. Census Bureau. March 1, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ More, Maggie (December 6, 2022). "All Hail the Northeast Megalopolis, the Census Bureau Region Home to Roughly 1 in 6 Americans". NBC4 Washington. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Olivo, Antonio (January 25, 2018). "Virginia's population growth is most robust in Washington suburbs". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Clabaugh, Jeff (August 9, 2017). "Booming Tysons, looming problems: Office vacancies, traffic headaches and more". WTOP. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ Cooper, Kyle (December 31, 2019). "Loudoun County one of the fastest growing in the country". WTOP. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Battiata, Mary (November 27, 2005). "Silent Streams". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ a b "American Community Survey: Age and Sex". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "NNSY History". United States Navy. August 27, 2007. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ "All About Suffolk". Suffolk. February 12, 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- ^ Ranaivo, Yann (January 31, 2020). "New population estimates: Montgomery County passes Roanoke". The Roanoke Star. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ "Resident Population and Apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. December 27, 2000. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Historical Population Change Data (1910–2020)". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Bureau, US Census (April 26, 2021). "2020 Census Apportionment Results". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Fertility Rate: Virginia, 2010–2020". March of Dimes. January 2022. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ "Centers of Population". U.S. Census Bureau. November 16, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Yancey, Dwayne (January 25, 2023). "Youngkin is worried about people moving out of Virginia. Here's how big that out-migration is". Cardinal News. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Montgomery, Mimi (February 14, 2023). "Is Richmond Turning Into the New Bedroom Community for DC Workers?". Washingtonian. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Peifer, Karri (January 17, 2023). "Northern Virginia residents are relocating to Richmond in droves". Axios. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Aisch, Gregor; Gebeloff, Robert; Quealy, Kevin (August 14, 2014). "Where We Came From and Where We Went, State by State". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b "A Profile of Our Immigrant Neighbors in Northern Virginia". The Commonwealth Institute. July 29, 2020. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Montanaro, Domenico (November 4, 2013). "Demographics are destiny in Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census". U.S. Census Bureau. August 17, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Miller et al. 2003, pp. 6, 147.

- ISBN 978-0-19-069257-5.

- S2CID 60711423.

- ISBN 978-0-19-503794-4.

- ^ a b Keller, Christian B. (2001). "Pennsylvania and Virginia Germans during the Civil War". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 109: 37–86. Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ O'Connor, Rosemarie (March 17, 2019). "Virginia is for Irish lovers?". Prince William Times. Capital News Service. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ Pinn 2009, p. 175; Chambers 2005, pp. 10–14

- ^ White, Michael (December 20, 2017). "How Slavery Changed the DNA of African Americans". Pacific Standard. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- PMID 25529636.

- ^ Frey, William H. (May 2004). "The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965–2000" (PDF). The Living Cities Census Series: 1–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 3, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ^ Watson, Denise M. (March 17, 2012). "Virginia ranks highest in U.S. for black-white marriages". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ Raby, John (February 3, 2011). "Virginians in the census: 8 million total, 1M in Fairfax County". The Virginian-Pilot. Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- JSTOR 215658.

- ^ Wilder, Layla (March 28, 2008). "Centreville: The New Koreatown?". Fairfax County Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Firestone, Nora (June 12, 2008). "Locals celebrate Philippine Independence Day". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Vogelsong, Sarah (November 22, 2023). "For 346th year, Virginia tribes present governor with a tribute of game". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved January 23, 2024.

- ^ Coleman, Arica L. (February 9, 2018). "From the 'Pocahontas Exception' to a 'Historical Wrong': The Hidden Cost of Formal Recognition for American Indian Tribes". Time Magazine. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Walburn Viviano, Meg (October 8, 2018). "Seven Virginia Tribes Celebrate Federal Recognition on York River". Chesapeake Bay Magazine. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ Hilleary, Cecily (January 31, 2018). "US Recognizes 6 Virginia Native American Tribes". Voice of America. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Manske, Madison; Zernik, Alexandra (May 7, 2019). "After centuries in Virginia, tribe still waiting for U.S. recognition". WHSV-TV. Capital News Service. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "State Immigration Data Profiles: Virginia". Migration Policy Institute. 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Joseph 2006, p. 63.

- ^ Rascoe, Ayesha (September 17, 2023). "Are Southern accents disappearing? Linguists say yes". NPR. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ a b "This accent is one of the most pleasant in the world". Augusta Free Press. December 10, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Laurence (September 2014). "8 American Dialects Most Brits Don't Know About". BBC America. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ Clay III, Edwin S.; Bangs, Patricia (May 9, 2005). "Virginia's Many Voices". Fairfax County, Virginia. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ Davis, Chelyen (July 26, 2015). "Davis: Appalachian code-switching". The Roanoke Times. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Rao, Veena; Stein, Eliot (February 7, 2018). "The tiny US island with a British accent". BBC. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ Miller, John J. (August 2, 2005). "Exotic Tangier". National Review. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center. 2014. Archived from the original on March 12, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ Vegh, Steven G. (November 10, 2006). "2nd Georgia church joins moderate Va. Baptist association". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ^ "SBCV passes 500 mark". Baptist Press. November 20, 2007. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ^ Mondale, Arthur (March 24, 2016). "JBM-HH chaplains: Easter Sunrise Service offers chance to celebrate, grow". Pentagram. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Boorstein, Michelle (March 10, 2014). "Supreme Court won't hear appeal of dispute over Episcopal Church's property in Va". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Walker, Lance. "USA-Virginia". Mormon Newsroom. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Henry, John (April 24, 2020). "DMV mosques adjust Ramadan observance during coronavirus pandemic". WUSA9. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Olitzky 1996, p. 359.

- ^ "Megachurch Search Results". Hartford Institute for Religion Research. 2008. Archived from the original on January 24, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ^ Burge, Ryan (July 3, 2019). "Rise of the 'nothing in particulars' may be sign of a disjointed, disaffected and lonely future". Religion News. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "SAINC1 State annual personal income summary: personal income, population, per capita personal income". U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. March 31, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ "GDP by State". GDP by State | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Bureau of Economic Analysis. December 23, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Pierceall, Kimberly (May 22, 2020). "Virginia's unemployment rate grows past 10 percent in April". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "Economy at a Glance". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. March 19, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ "Unemployment Rates for States, Seasonally Adjusted". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. April 19, 2024. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Hamza, Adam (October 4, 2019). "Data show poverty and income trends in Virginia". NBC12. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ "SOH: State and CoC Dashboards". National Alliance to End Homelessness. 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ "25 Wealthiest Counties in the US". Yahoo! News. December 1, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Belt, Deb (October 3, 2019). "Virginia Poverty Rate Stable, Loudoun County Has Top Income". Patch Leesburg. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ Sauter, Michael B. (February 17, 2020). "Income It Takes to Be Considered Middle Class in Every State". 24/7 Wall St. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Clabaugh, Jeff (July 11, 2023). "Virginia rises to No. 2 on CNBC's Best States for Business list". WTOP. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ Main, Kelly; Bottorff, Cassie (November 30, 2022). "Ranked: The Best States To Start a Business In 2023". Forbes. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Best and Worst States for Business Owners". Fundivo. August 27, 2014. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Best States to Work 2022". Oxfam America. August 30, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ Michael, Karen (July 4, 2016). "Labor Law: No notice required to terminate an "at will" employee". The Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Levitz, Eric (February 11, 2020). "VA Democrats Kill Pro-Union Bill After Learning CEOs Oppose It". New York Magazine. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Webb, Andrew (January 2, 2023). "Virginia's minimum wage increases to $12". WDBJ7. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Vogel, Steve (May 27, 2007). "How the Pentagon Got Its Shape". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ "Virginia Economy at a Glance". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. February 6, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- Fox Business Network. Archived from the originalon February 1, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Ellis, Nicole Anderson (September 1, 2008). "Virginia weighs its dependence on defense spending". Virginia Business. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Virginia State Profile" (PDF). Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration Program. March 2, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Chmura, Christine (July 7, 2019). "Economic Impact: The number of defense contracts in Virginia continues to increase, which is good news for the state's economy". The Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ Gilligan, Chris (November 11, 2022). "These States Have the Highest Percentage of Veterans". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ "2018-19 salaries of Virginia state employees". The Richmond Times-Dispatch. November 1, 2018. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "Commonwealth Data Point Budget". Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts. 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ "Which states pay teachers the most and least?". USA Facts. November 20, 2023. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ Foster, Richard (July 28, 2022). "S Virginia's Fortune 500 companies". Virginia Business. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Kolmar, Chris (February 2020). "The 100 Largest Companies In Virginia For 2020". Zippa.com. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "Cyberstates 2021" (PDF) (Press release). CompTIA. March 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ Barthel, Margaret (September 1, 2023). "Northern Virginia's Data Center Industry Is Booming. But Is It Sustainble?". DCist. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Overman, Stephenie (March 1, 2020). "You Can Google It". Virginia Business. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ Vogelsong, Sarah (May 5, 2021). "Data centers and electric vehicles will drive up Virginia electricity demand, UVA forecaster predicts". The Virginia Mercury. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ Olivo, Antonio (February 10, 2023). "Northern Va. is the heart of the internet. Not everyone is happy about that". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Holslin, Peter; Armstrong, Rebecca Lee (April 13, 2022). "The 10 Fastest and Slowest States for Internet Speeds in 2022". HighSpeedInternet.com. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Shevik, Jason (August 8, 2023). "Best & Worst States for Broadband, 2023". BroadbandNow. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Richards, Gregory (February 24, 2007). "Computer chips now lead Virginia exports". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- ^ "Virginia Export and Import Data" (PDF). Virginia Economic Development Partnership. February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Peifer, Karri (October 18, 2022). "Virginia tourism rebounds with Henrico leading the Richmond region". Axios Richmond. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Laura (June 10, 2019). "Governor Northam says tourism revenues reach $26 billion in Virginia in 2018". WSET-TV. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Gambrell, Holly (September 30, 2019). "Northern Virginia leads state's tourism with 3 local counties topping the list". Northern Virginia Magazine. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Patterson, Erin (October 23, 2019). "International tourism to Virginia reaches record level". 13NewsNow. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Howard, Maria (August 30, 2023). "Growth industry: Agriculture powers valley jobs, investment". Virginia Business. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "Virginia Agriculture—Facts and Figures". Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "Virginia's Top 20 Farm Commodities". Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. November 30, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Vogelsong, Sarah (January 17, 2020). "2019 was good for cotton, bad for soybeans and tobacco in Virginia". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "Facts About The Virginia Commercial Seafood Industry 2023". Virginia Seafood and Virginia Marine Products Board. September 22, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Sparks, Lisa Vernon (April 21, 2020). "Virginia's fishing industry has lost millions because of coronavirus pandemic, internal memo says". The Daily Press. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Larsen, Patrick (January 8, 2024). "Virginia oyster harvest hits milestone". VPM. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Dayna (November 11, 2023). "2023 could be a banner year for Virginia wine". The Daily Progress. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Hutton, Alyssa (October 20, 2023). "Virginia Lift's A Toast To Its Thriving Wine Industry". The Roanoke Star. Capital News Service. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "Statistics". Wines Vines Analytics. January 2024. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Luck, Jessica (October 27, 2017). "Crushing it: Why this year's harvest could put Virginia wine on the national map". C-Ville. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ Baker, Nicolette (June 29, 2023). "The States That Produce the Most Craft Beer (2023)". VinePair. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ "Individual Income Tax". Virginia Department of Taxation. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Scarboro, Morgan (March 2018). Fiscal Fact No. 576: State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2018 (PDF) (Report). Tax Foundation.

- ^ a b "Retail Sales and Use Tax". Virginia Department of Taxation. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Figueroa, Eric; Legendre, Juliette (April 1, 2020). "States That Still Impose Sales Taxes on Groceries Should Consider Reducing or Eliminating Them". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- ^ Montesinos, Patsy (January 2, 2023). "Grocery sales tax reduction begins in Virginia". WDJB7. Gray Television, Inc. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ Kulp, Stephen C. (January 2018). Virginia Local Tax Rates, 2017 (PDF) (Report) (36th annual ed.). Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, University of Virginia/LexisNexis. p. 7.

- ^ Compton, Roderick (March 2, 2023). "The Virginia Assessment/Sales Ratio Study For Tax Year 2021" (PDF). Virginia Department of Taxation.

- ^ Kulp, Stephen C. (January 2018). Virginia Local Tax Rates, 2017 (PDF) (Report) (36th annual ed.). Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, University of Virginia/LexisNexis. p. viii.

- ^ Fischer & Kelly 2000, pp. 102–103.

- ^ "Roots of Virginia Culture" (PDF). Smithsonian Folklife Festival 2007. Smithsonian Institution. July 5, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- ^ McGraw 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Williamson 2008, p. 41.

- ^ Gray & Robinson 2004, pp. 81, 103.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Mary Alice. "Summary of Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice". Library of Southern Literature. University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (November 2, 2006). "William Styron, Novelist, Dies at 81". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Dirda, Michael (November 7, 2004). "A Coed in Full". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ^ Jackman, Tom (May 27, 2012). "Fairfax native Matt Bondurant's book is now the movie 'Lawless'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 28, 2012. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ Fain, Travis (June 27, 2014). "Gov. taps new OIG, elections chief, hires House member". Daily Press. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "State Arts Agency Revenues" (PDF) (Press release). National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. February 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Howard, Burnham & Burnham 2006, pp. 88, 206, 292.

- Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. 2007. Archived from the originalon August 27, 2007. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ Howard, Burnham & Burnham 2006, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Goodwin 2012, p. 154.

- ^ Prestidge, Holly (January 18, 2013). "Theater legacies: Theatre IV founders embark on a new adventure". The Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Howard, Burnham & Burnham 2006, pp. 29, 121, 363, 432.

- ^ a b Scott & Scott 2004, pp. 307–308

- ^ "The Roots and Branches of Virginia Music". Folkways. Smithsonian Institution. 2007. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Belcher, Craig (September 25, 2018). "Virginia's Greatest Show Never". Richmond Magazine. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Pace, Reggie (August 14, 2013). "12 Virginia Bands You Should Listen to Now". Paste. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Dickens, Tad (June 3, 2014). "Old Dominion country band has Roanoke Valley roots". The Roanoke Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Reese, Brian (July 25, 2023). "Chincoteague holds 2023 Pony Swim on Wednesday". WAVY. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Goodwin 2012, pp. 25, 287.

- ^ Meyer, Marianne (June 7, 2007). "Live!". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ^ "Sweet Summertime". Virginia Living. July 19, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2024.

- ^ Crane, John R. (January 21, 2022). "After legal action, payments flow to companies owed by Blue Ridge Rock Festival". Danville Register & Bee. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ^ Goodwin 2012, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Jacobs, Jack (July 30, 2019). "General Assembly commemorates origins of democracy in America". The Virginia Gazette. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- JSTOR 1978427.

- ^ Paviour, Ben (April 18, 2019). "Two-Term Virginia Governors Rare, But Not Unprecedented". VPM. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "Your Guide to the Virginia General Assembly" (PDF). Virginia General Assembly. May 10, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ "LIST: Virginia Gov.-elect Youngkin's full roster of Cabinet appointees". 7News. January 13, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2023.