Virology

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, their interaction with host organism physiology and immunity, the diseases they cause, the techniques to isolate and culture them, and their use in research and therapy.

The identification of the causative agent of

One main motivation for the study of viruses is because they cause many infectious diseases of plants and animals.

Virology began when there were no methods for propagating or visualizing viruses or specific laboratory tests for viral infections. The methods for separating viral nucleic acids (RNA and DNA) and proteins, which are now the mainstay of virology, did not exist. Now there are many methods for observing the structure and functions of viruses and their component parts. Thousands of different viruses are now known about and virologists often specialize in either the viruses that infect plants, or bacteria and other microorganisms, or animals. Viruses that infect humans are now studied by medical virologists. Virology is a broad subject covering biology, health, animal welfare, agriculture and ecology.

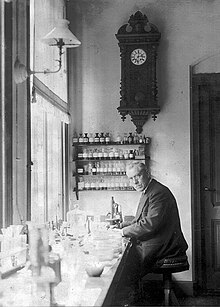

History

Louis Pasteur was unable to find a causative agent for rabies and speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected by microscopes.[4] In 1884, the French microbiologist Charles Chamberland invented the Chamberland filter (or Pasteur-Chamberland filter) with pores small enough to remove all bacteria from a solution passed through it.[5] In 1892, the Russian biologist Dmitri Ivanovsky used this filter to study what is now known as the tobacco mosaic virus: crushed leaf extracts from infected tobacco plants remained infectious even after filtration to remove bacteria. Ivanovsky suggested the infection might be caused by a toxin produced by bacteria, but he did not pursue the idea.[6] At the time it was thought that all infectious agents could be retained by filters and grown on a nutrient medium—this was part of the germ theory of disease.[7]

In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist

In the early 20th century, the English bacteriologist

By the end of the 19th century, viruses were defined in terms of their infectivity, their ability to pass filters, and their requirement for living hosts. Viruses had been grown only in plants and animals. In 1906 Ross Granville Harrison invented a method for growing tissue in lymph, and in 1913 E. Steinhardt, C. Israeli, and R.A. Lambert used this method to grow vaccinia virus in fragments of guinea pig corneal tissue.[13] In 1928, H. B. Maitland and M. C. Maitland grew vaccinia virus in suspensions of minced hens' kidneys. Their method was not widely adopted until the 1950s when poliovirus was grown on a large scale for vaccine production.[14]

Another breakthrough came in 1931 when the American pathologist

The first images of viruses were obtained upon the invention of

The second half of the 20th century was the golden age of virus discovery, and most of the documented species of animal, plant, and bacterial viruses were discovered during these years.

Detecting viruses

There are several approaches to detecting viruses and these include the detection of virus particles (virions) or their

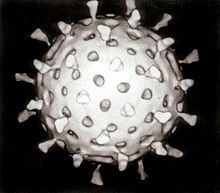

Electron microscopy

Viruses were seen for the first time in the 1930s when electron microscopes were invented. These microscopes use beams of electrons instead of light, which have a much shorter wavelength and can detect objects that cannot be seen using light microscopes. The highest magnification obtainable by electron microscopes is up to 10,000,000 times[29] whereas for light microscopes it is around 1,500 times.[30]

Virologists often use

Traditional electron microscopy has disadvantages in that viruses are damaged by drying in the high vacuum inside the electron microscope and the electron beam itself is destructive.

Growth in cultures

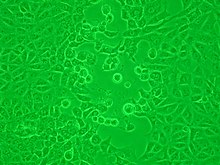

Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites and because they only reproduce inside the living cells of a host these cells are needed to grow them in the laboratory. For viruses that infect animals (usually called "animal viruses") cells grown in laboratory

Viruses that have grown in cell cultures can be indirectly detected by the detrimental effect they have on the host cell. These

Viruses growing in cell cultures are used to measure their susceptibility to validated and novel antiviral drugs.[40]

Serology

Viruses are

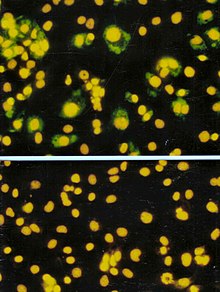

In the years before PCR was invented immunofluorescence was used to quickly confirm viral infections. It is an infectivity assay that is virus species specific because antibodies are used. The antibodies are tagged with a dye that is luminescencent and when using an optical microscope with a modified light source, infected cells glow in the dark.[45]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other nucleic acid detection methods

PCR is a mainstay method for detecting viruses in all species including plants and animals. It works by detecting traces of virus specific RNA or DNA. It is very sensitive and specific, but can be easily compromised by contamination. Most of the tests used in veterinary virology and medical virology are based on PCR or similar methods such as

Diagnostic tests

In laboratories many of the diagnostic test for detecting viruses are nucleic acid amplification methods such as PCR. Some tests detect the viruses or their components as these include electron microscopy and enzyme-immunoassays. The so-called "home" or "self"-testing gadgets are usually lateral flow tests, which detect the virus using a tagged monoclonal antibody.[49] These are also used in agriculture, food and environmental sciences.[50]

Quantitation and viral loads

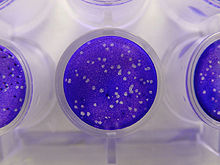

Counting viruses (quantitation) has always had an important role in virology and has become central to the control of some infections of humans where the viral load is measured.[51] There are two basic methods: those that count the fully infective virus particles, which are called infectivity assays, and those that count all the particles including the defective ones.[29]

Infectivity assays

Infectivity assays measure the amount (concentration) of infective viruses in a sample of known volume.

The focus forming assay (FFA) is a variation of the plaque assay, but instead of relying on cell lysis in order to detect plaque formation, the FFA employs

Viral load assays

When an assay for measuring the infective virus particle is done (Plaque assay, Focus assay), viral titre often refers to the concentration of infectious viral particles, which is different from the total viral particles. Viral load assays usually count the number of viral genomes present rather than the number of particles and use methods similar to PCR.[57] Viral load tests are an important in the control of infections by HIV.[58] This versatile method can be used for plant viruses.[59][60]

Molecular biology

Molecular virology is the study of viruses at the level of nucleic acids and proteins. The methods invented by molecular biologists have all proven useful in virology. Their small sizes and relatively simple structures make viruses an ideal candidate for study by these techniques.

Purifying viruses and their components

For further study, viruses grown in the laboratory need purifying to remove contaminants from the host cells. The methods used often have the advantage of concentrating the viruses, which makes it easier to investigate them.

Centrifugation

Centrifuges are often used to purify viruses. Low speed centrifuges, i.e. those with a top speed of 10,000 revolutions per minute (rpm) are not powerful enough to concentrate viruses, but ultracentrifuges with a top speed of around 100,000 rpm, are and this difference is used in a method called differential centrifugation. In this method the larger and heavier contaminants are removed from a virus mixture by low speed centrifugation. The viruses, which are small and light and are left in suspension, are then concentrated by high speed centrifugation.[62]

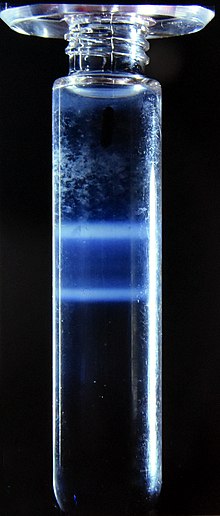

Following differential centrifugation, virus suspensions often remain contaminated with debris that has the same sedimentation coefficient and are not removed by the procedure. In these cases a modification of centrifugation, called buoyant density centrifugation, is used. In this method the viruses recovered from differential centrifugation are centrifuged again at very high speed for several hours in dense solutions of sugars or salts that form a density gradient, from low to high, in the tube during the centrifugation. In some cases, preformed gradients are used where solutions of steadily decreasing density are carefully overlaid on each other. Like an object in the Dead Sea, despite the centrifugal force the virus particles cannot sink into solutions that are more dense than they are and they form discrete layers of, often visible, concentrated viruses in the tube. Caesium chloride is often used for these solutions as it is relatively inert but easily self-forms a gradient when centrifuged at high speed in an ultracentrifuge.[61] Buoyant density centrifugation can also be used to purify the components of viruses such as their nucleic acids or proteins.[63]

Electrophoresis

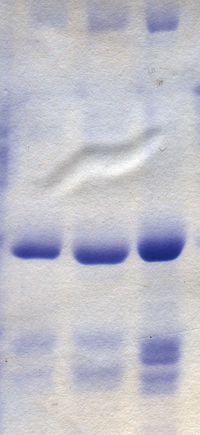

The separation of molecules based on their electric charge is called

Sequencing of viral genomes

As most viruses are too small to be seen by a light microscope, sequencing is one of the main tools in virology to identify and study the virus. Traditional Sanger sequencing and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are used to sequence viruses in basic and clinical research, as well as for the diagnosis of emerging viral infections, molecular epidemiology of viral pathogens, and drug-resistance testing. There are more than 2.3 million unique viral sequences in GenBank.[65] NGS has surpassed traditional Sanger as the most popular approach for generating viral genomes.[65] Viral genome sequencing as become a central method in viral epidemiology and viral classification.

Phylogenetic analysis

Data from the sequencing of viral genomes can be used to determine evolutionary relationships and this is called

Cloning

When purified viruses or viral components are needed for diagnostic tests or vaccines, cloning can be used instead of growing the viruses.

Phage virology

The viruses that reproduce in bacteria, archaea and fungi are informally called "phages",

Genetics

All viruses have genes which are studied using genetics.[75] All the techniques used in molecular biology, such as cloning, creating mutations RNA silencing are used in viral genetics.[76]

Reassortment

Recombination

Often confused with reassortment, recombination is also the mixing of genes but the mechanism differs in that stretches of DNA or RNA molecules, as opposed to the full molecules, are joined during the RNA or DNA replication cycle. Recombination is not as common as reassortment in nature but it is a powerful tool in laboratories for studying the structure and functions of viral genes.[78]

Reverse genetics

Reverse genetics is a powerful research method in virology.[79] In this procedure complementary DNA (cDNA) copies of virus genomes called "infectious clones" are used to produce genetically modified viruses that can be then tested for changes in say, virulence or transmissibility.[80]

Virus classification

A major branch of virology is

ICTV classification

The ICTV developed the current classification system and wrote guidelines that put a greater weight on certain virus properties to maintain family uniformity. A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established. Only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied.[90] As of 2021, 6 realms, 10 kingdoms, 17 phyla, 2 subphyla, 39 classes, 65 orders, 8 suborders, 233 families, 168 subfamilies, 2,606 genera, 84 subgenera, and 10,434 species of viruses have been defined by the ICTV.[91]

The general taxonomic structure of taxon ranges and the suffixes used in taxonomic names are shown hereafter. As of 2021, the ranks of subrealm, subkingdom, and subclass are unused, whereas all other ranks are in use.[91]

- Realm (-viria)

Baltimore classification

The Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore devised the Baltimore classification system.[92]

The Baltimore classification of viruses is based on the mechanism of

- I: Poxviruses)

- II: Parvoviruses)

- III: Reoviruses)

- IV:Togaviruses)

- V: Rhabdoviruses)

- VI: ssRNA-RT viruses (+ strand or sense) RNA with DNA intermediate in life-cycle (e.g. Retroviruses)

- VII: Hepadnaviruses)

References

- PMID 22408703.

- PMID 25462446.

- PMID 33926472.

- PMID 12758285.

- ^ Shors pp. 74, 827

- ^ a b Collier p. 3

- ^ Dimmock p. 4

- ^ Dimmock pp. 4–5

- ISBN 978-0-12-375146-1.

- ^ Shors p. 827

- PMID 17855060.

- S2CID 29223662.

- .

- ^ Collier p. 4

- PMID 17810781.

- ISBN 978-0-88135-380-8.

- PMID 15470207.

- Bibcode:1993nlp..book.....F.

- In 1887, Buist visualised one of the largest, Vaccinia virus, by optical microscopy after staining it. Vaccinia was not known to be a virus at that time. (Buist J.B. Vaccinia and Variola: a study of their life history Churchill, London)

- PMID 17756690.

- PMID 17788438.

- S2CID 25741967.

- ^ Dimmock p. 12

- S2CID 10595263.

- ^ Collier p. 745

- PMID 4348509.

- PMID 6189183.

- PMID 2523562.

- PMID 19781804.

- ^ a b c d Payne S. Methods to Study Viruses. Viruses. 2017;37-52. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803109-4.00004-0

- ^ "Magnification - Microscopy, size and magnification (CCEA) - GCSE Biology (Single Science) Revision - CCEA". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- PMID 13804200.

- PMID 19822888.

- PMID 18793481.

- PMID 25910204.

- . Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- S2CID 41236532.

- PMID 35050076.

- PMID 24899440.

- S2CID 218504421.

- PMID 32056049.

- PMID 32342927.

- PMID 1365549.

- PMID 21887208.

- S2CID 24960083.

- PMID 32197545.

- PMID 32815744.

- PMID 35300739.

- PMID 33219449.

- PMC 7149825

- PMID 27365041.

- PMID 34369836.

- PMID 29925033.

- PMID 15585191.

- PMID 21474258.

- S2CID 232023531.

- PMID 28701394.

- PMID 33627730.

- PMID 31515967.

- PMID 28315718.

- PMID 32765569.

- ^ PMID 6290520.

- PMID 32825599.

- S2CID 143423942.

- S2CID 41587013.

- ^ PMID 32571214.

- PMID 30531947.

- ^ Gorbalenya AE, Lauber C. Phylogeny of Viruses. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences. 2017;B978-0-12-801238-3.95723-4. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.95723-4

- PMID 32404960.

- S2CID 213516085.

- PMID 31219641.

- PMID 16791793.

- S2CID 46921731.

- ^ PMID 31216787.

- PMID 33504115.

- S2CID 21736957.

- OCLC 1240584737.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - PMID 27211789.

- PMID 22922205.

- PMID 24899418.

- PMID 33528730.

- S2CID 220907379.

- PMID 25015480.

- PMID 30039318.

- PMID 14467544.

- PMID 13931895.

- PMID 16105179.

- PMID 32341570.

- PMID 34226482.

- S2CID 5642060.

- PMID 17295196.

- ^ a b "Virus Taxonomy: 2021 Release". talk.ictvonline.org. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- S2CID 235821748.

Bibliography

- Collier L, Balows A, Sussman M (1998). Mahy B, Collier LA (eds.). Topley and Wilson's Microbiology and Microbial Infections. Virology. Vol. 1 (Ninth ed.). ISBN 0-340-66316-2.

- Dimmock NJ, Easton AJ, Leppard K (2007). Introduction to Modern Virology (Sixth ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3645-7.

- Shors T (2017). Understanding Viruses. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-284-02592-7.

External links

Media related to Virology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Virology at Wikimedia Commons- Official website of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses