Vitamin C

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˈskɔːrbɪk/, /əˈskɔːrbeɪt, -bɪt/ |

| Trade names | Ascor, Cecon, Cevalin, others |

| Other names | l-ascorbic acid, ascorbic acid, ascorbate |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682583 |

| License data | |

subcutaneous | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Rapid, diminishes as dose increases[4] |

| Protein binding | Negligible |

| Elimination half-life | Varies according to plasma concentration |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.694 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 190 to 192 °C (374 to 378 °F) |

| Boiling point | 552.7 °C (1,026.9 °F) [5] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Vitamin C (also known as

Vitamin C is an essential nutrient involved in the repair of tissue, the formation of collagen, and the enzymatic production of certain neurotransmitters. It is required for the functioning of several enzymes and is important for immune system function.[6] It also functions as an antioxidant. Vitamin C may be taken by mouth or by intramuscular, subcutaneous or intravenous injection. Various health claims exist on the basis that moderate vitamin C deficiency increases disease risk, such as for the common cold, cancer or COVID-19. There are also claims of benefits from vitamin C supplementation in excess of the recommended dietary intake for people who are not considered vitamin C deficient. Vitamin C is generally well-tolerated. Large doses may cause gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, trouble sleeping, and flushing of the skin. The United States Institute of Medicine recommends against consuming large amounts.[7]: 155–165

Most animals are able to

Vitamin C was discovered in 1912, isolated in 1928, and in 1933, was the first vitamin to be chemically produced. Partly for its discovery, Albert Szent-Györgyi was awarded the 1937 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Chemistry

(reduced form)

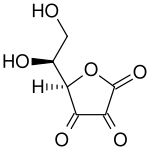

The name "vitamin C" always refers to the

Numerous analytical methods have been developed for ascorbic acid detection. For example, vitamin C content of a food sample such as fruit juice can be calculated by measuring the volume of the sample required to decolorize a solution of dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) and then calibrating the results by comparison with a known concentration of vitamin C.[9][10]

Deficiency

Plasma vitamin C is the most widely applied test for vitamin C status.

Plasma levels are considered saturated at about 65 μmol/L, achieved by intakes of 100 to 200 mg/day, which are well above the recommended intakes. Even higher oral intake does not further raise plasma nor tissue concentrations because absorption efficiency decreases and any excess that is absorbed is excreted in urine.[8]

Diagnostic testing

Vitamin C content in plasma is used to determine vitamin status. For research purposes, concentrations can be assessed in

Diet

Recommended consumption

Recommendations for vitamin C intake by adults have been set by various national agencies:

- 40 mg/day: India National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad[15]

- 45 mg/day or 300 mg/week: the World Health Organization[16]

- 80 mg/day: the European Commission Council on nutrition labeling[17]

- 90 mg/day (males) and 75 mg/day (females): Health Canada 2007[18]

- 90 mg/day (males) and 75 mg/day (females): United States National Academy of Sciences[7]: 134–152

- 100 mg/day: Japan National Institute of Health and Nutrition[19]

- 110 mg/day (males) and 95 mg/day (females): European Food Safety Authority[20]

| US vitamin C recommendations ( mg per day)[7] : 134–152

| |

|---|---|

| RDA (children ages 1–3 years) | 15 |

| RDA (children ages 4–8 years) | 25 |

| RDA (children ages 9–13 years) | 45 |

| RDA (girls ages 14–18 years) | 65 |

| RDA (boys ages 14–18 years) | 75 |

| RDA (adult female) | 75 |

| RDA (adult male) | 90 |

| RDA (pregnancy) | 85 |

| RDA (lactation) | 120 |

| UL (adult female) | 2,000 |

| UL (adult male) | 2,000 |

In 2000, the chapter on Vitamin C in the North American

For the European Union, the EFSA set higher recommendations for adults, and also for children: 20 mg/day for ages 1–3, 30 mg/day for ages 4–6, 45 mg/day for ages 7–10, 70 mg/day for ages 11–14, 100 mg/day for males ages 15–17, 90 mg/day for females ages 15–17. For pregnancy 100 mg/day; for lactation 155 mg/day.[20]

Cigarette smokers and people exposed to secondhand smoke have lower serum vitamin C levels than nonsmokers.[11] The thinking is that inhalation of smoke causes oxidative damage, depleting this antioxidant vitamin.[7]: 152–153 The US Institute of Medicine estimated that smokers need 35 mg more vitamin C per day than nonsmokers, but did not formally establish a higher RDA for smokers.[7]: 152–153 An inverse relationship between vitamin C intake and lung cancer was observed, although the conculsion was that more research is needed to confirm this observation.[21]

The US National Center for Health Statistics conducts biannual National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States. Some results are reported as What We Eat In America. The 2013–2014 survey reported that for adults ages 20 years and older, men consumed on average 83.3 mg/d and women 75.1 mg/d. This means that half the women and more than half the men are not consuming the RDA for vitamin C.[22] The same survey stated that about 30% of adults reported they consumed a vitamin C dietary supplement or a multi-vitamin/mineral supplement that included vitamin C, and that for these people total consumption was between 300 and 400 mg/d.[23]

Tolerable upper intake level

In 2000, the Institute of Medicine of the US National Academy of Sciences set a

Food labeling

For US food and dietary supplement labeling purposes, the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For vitamin C labeling purposes, 100% of the Daily Value was 60 mg, but as of May 27, 2016, it was revised to 90 mg to bring it into agreement with the RDA.[25][26] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

European Union regulations require that labels declare energy, protein, fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, sugars, and salt. Voluntary nutrients may be shown if present in significant amounts. Instead of Daily Values, amounts are shown as percent of Reference Intakes (RIs). For vitamin C, 100% RI was set at 80 mg in 2011.[27]

Sources

Although also present in other plant-derived foods, the richest natural sources of vitamin C are fruits and vegetables.[4][6] Vitamin C is the most widely taken dietary supplement.[6]

Plant sources

The following table is approximate and shows the relative abundance in different raw plant sources.[4][6][28] The amount is given in milligrams per 100 grams of the edible portion of the fruit or vegetable:

| Raw plant source[29] | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Kakadu plum | 1000–5300[30] |

Camu camu |

2800[31] |

Acerola |

1677[32] |

Indian gooseberry |

445[33][34] |

| Rose hip | 426 |

Common sea-buckthorn |

400[35] |

| Guava | 228 |

| Blackcurrant | 200 |

| Yellow bell pepper/capsicum | 183 |

| Red bell pepper/capsicum | 128 |

| Kale | 120 |

| Broccoli | 90 |

| Kiwifruit | 90 |

| Raw plant source[29] | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Green bell pepper/capsicum | 80 |

| Brussels sprouts | 80 |

| Loganberry, redcurrant | 80 |

elderberry |

60 |

| Strawberry | 60 |

| Papaya | 60 |

| Orange, lemon | 53 |

| Cauliflower | 48 |

| Pineapple | 48 |

| Cantaloupe | 40 |

Passion fruit, raspberry |

30 |

| Grapefruit, lime | 30 |

| Cabbage, spinach | 30 |

| Raw plant source[29] | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Mango | 28 |

| Blackberry, cassava | 21 |

| Potato | 20 |

Honeydew melon |

20 |

| Tomato | 14 |

| Cranberry | 13 |

| Blueberry, grape | 10 |

| Apricot, plum, watermelon | 10 |

| Avocado | 8.8 |

| Onion | 7.4 |

| Cherry, peach | 7 |

| Apple | 6 |

| Carrot, asparagus | 6 |

Animal sources

Compared to plant sources, animal-sourced foods do not provide so great an amount of vitamin C, and what there is is largely destroyed by the heat used when it is cooked. For example, raw chicken liver contains 17.9 mg/100 g, but fried, the content is reduced to 2.7 mg/100 g. Vitamin C is present in human breast milk at 5.0 mg/100 g. Cow's milk contains 1.0 mg/100 g, but the heat of pasteurization destroys it.[36]

Food preparation

Vitamin C chemically decomposes under certain conditions, many of which may occur during the cooking of food. Vitamin C concentrations in various food substances decrease with time in proportion to the temperature at which they are stored.[37] Cooking can reduce the vitamin C content of vegetables by around 60%, possibly due to increased enzymatic destruction.[38] Longer cooking times may add to this effect.[39] Another cause of vitamin C loss from food is leaching, which transfers vitamin C to the cooking water, which is decanted and not consumed.[40]

Supplements

Vitamin C dietary supplements are available as tablets, capsules, drink mix packets, in multi-vitamin/mineral formulations, in antioxidant formulations, and as crystalline powder.[41] Vitamin C is also added to some fruit juices and juice drinks. Tablet and capsule content ranges from 25 mg to 1500 mg per serving. The most commonly used supplement compounds are ascorbic acid, sodium ascorbate and calcium ascorbate.[41] Vitamin C molecules can also be bound to the fatty acid palmitate, creating ascorbyl palmitate, or else incorporated into liposomes.[42]

Food fortification

Countries fortify foods with nutrients to address known deficiencies.[43] While many countries mandate or have voluntary programs to fortify wheat flour, maize (corn) flour or rice with vitamins,[44] none include vitamin C in those programs.[44] As described in Vitamin C Fortification of Food Aid Commodities (1997), the United States provides rations to international food relief programs, later under the asupices of the Food for Peace Act and the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance.[45] Vitamin C is added to corn-soy blend and wheat-soy blend products at 40 mg/100 grams. (along with minerals and other vitamins). Supplemental rations of these highly fortified, blended foods are provided to refugees and displaced persons in camps and to beneficiaries of development feeding programs that are targeted largely toward mothers and children.[40] The report adds: "The stability of vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) is of concern because this is one of the most labile vitamins in foods. Its main loss during processing and storage is from oxidation, which is accelerated by light, oxygen, heat, increased pH, high moisture content (water activity), and the presence of copper or ferrous salts. To reduce oxidation, the vitamin C used in commodity fortification is coated with ethyl cellulose (2.5 percent). Oxidative losses also occur during food processing and preparation, and additional vitamin C may be lost if it dissolves into cooking liquid and is then discarded."[40]

Food preservation additive

Ascorbic acid and some of its

- E300 ascorbic acid (approved for use as a food additive in the UK,[49] US[50] Canada,[51] Australia and New Zealand[52])

- E301 sodium ascorbate (approved for use as a food additive in the UK,[49] US,[53] Canada,[51] Australia and New Zealand[52])

- E302 calcium ascorbate (approved for use as a food additive in the UK,[49] US[50] Canada,[51] Australia and New Zealand[52])

- E303 potassium ascorbate (approved in Australia and New Zealand,[52] but not in the UK, US or Canada)

- E304 fatty acid esters of ascorbic acid such as ascorbyl palmitate (approved for use as a food additive in the UK,[49] US,[50] Canada,[51] Australia and New Zealand[52])

The stereoisomers of Vitamin C have a similar effect in food despite their lack of efficacy in humans. They include erythorbic acid and its sodium salt (E315, E316).[49]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics is the study of how the drug – in this instance vitamin C – affects the organism, whereas pharmacokinetics is the study of how an organism affects the drug.

Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamics includes enzymes for which vitamin C is a cofactor, with function potentially compromised in a deficiency state, and any enzyme cofactor or other physiological function affected by administration of vitamin C, orally or injected, in excess of normal requirements. At normal physiological concentrations, vitamin C serves as an

Vitamin C functions as a cofactor for the following enzymes:[8]

- Three groups of enzymes (prolyl hydroxylase and lysyl hydroxylase, both requiring vitamin C as a cofactor. The role of vitamin C as a cofactor is to oxidize prolyl hydroxylase and lysyl hydroxylase from Fe2+ to Fe3+ and to reduce it from Fe3+ to Fe2+. Hydroxylation allows the collagen molecule to assume its triple helix structure, and thus vitamin C is essential to the development and maintenance of scar tissue, blood vessels, and cartilage.

- Two enzymes (mitochondria for ATPgeneration.

- Hypoxia-inducible factor-proline dioxygenase enzymes (isoforms: EGLN1, EGLN2, and EGLN3) allows cells to respond physiologically to low concentrations of oxygen.

- Dopamine beta-hydroxylase participates in the biosynthesis of norepinephrine from dopamine.

- Peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase amidates peptide hormones by removing the glyoxylate residue from their c-terminal glycine residues. This increases peptide hormone stability and activity.

As an antioxidant, ascorbate scavenges reactive oxygen and nitrogen compounds, thus neutralizing the potential tissue damage of these

Pharmacokinetics

Ascorbic acid is absorbed in the body by both simple diffusion and active transport.[57] Approximately 70%–90% of vitamin C is absorbed at moderate intakes of 30–180 mg/day. However, at doses above 1,000 mg/day, absorption falls to less than 50% as the active transport system becomes saturated.[4] Active transport is managed by Sodium-Ascorbate Co-Transporter proteins (SVCTs) and Hexose Transporter proteins (GLUTs). SVCT1 and SVCT2 import ascorbate across plasma membranes.[58] The Hexose Transporter proteins GLUT1, GLUT3 and GLUT4 transfer only the oxydized dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) form of vitamin C.[59][60] The amount of DHA found in plasma and tissues under normal conditions is low, as cells rapidly reduce DHA to ascorbate.[61]

SVCTs are the predominant system for vitamin C transport within the body.[58] In both vitamin C synthesizers (example: rat) and non-synthesizers (example: human) cells maintain ascorbic acid concentrations much higher than the approximately 50 micromoles/liter (µmol/L) found in plasma. For example, the ascorbic acid content of pituitary and adrenal glands can exceed 2,000 µmol/L, and muscle is at 200–300 µmol/L.[62] The known coenzymatic functions of ascorbic acid do not require such high concentrations, so there may be other, as yet unknown functions. A consequence of all this high concentration organ content is that plasma vitamin C is not a good indicator of whole-body status, and people may vary in the amount of time needed to show symptoms of deficiency when consuming a diet very low in vitamin C.[62]

Excretion (via urine) is as ascorbic acid and metabolites. The fraction that is excreted as unmetabolized ascorbic acid increases as intake increases. In addition, ascorbic acid converts (reversibly) to DHA and from that compound non-reversibly to 2,3-diketogulonate and then oxalate. These three metabolites are also excreted via urine. During times of low dietary intake, vitamin C is reabsorbed by the kidneys rather than excreted. This salvage process delays onset of deficiency. Humans are better than guinea pigs at converting DHA back to ascorbate, and thus take much longer to become vitamin C deficient.[8][60]

Synthesis

Most animals and plants are able to synthesize vitamin C through a sequence of

Animal synthesis

There is some information on serum vitamin C concentrations maintained in animal species that are able to synthesize vitamin C. One study of several breeds of dogs reported an average of 35.9 μmol/L.[71] A report on goats, sheep and cattle reported ranges of 100–110, 265–270 and 160–350 μmol/L, respectively.[72]

The biosynthesis of ascorbic acid in

Non-synthesizers

Some mammals have lost the ability to synthesize vitamin C, including simians and tarsiers, which together make up one of two major primate suborders, Haplorhini. This group includes humans. The other more primitive primates (Strepsirrhini) have the ability to make vitamin C. Synthesis does not occur in some species in the rodent family Caviidae, which includes guinea pigs and capybaras, but does occur in other rodents, including rats and mice.[74]

Synthesis does not occur in most bat species,

On a milligram consumed per kilogram of body weight basis, simian non-synthesizer species consume the vitamin in amounts 10 to 20 times higher than what is recommended by governments for humans.[81] This discrepancy constituted some of the basis of the controversy on human recommended dietary allowances being set too low.[82] However, simian consumption does not indicate simian requirements. Merck's veterinary manual states that daily intake of vitamin C at 3–6 mg/kg prevents scurvy in non-human primates.[83] By way of comparison, across several countries, the recommended dietary intake for adult humans is in the range of 1–2 mg/kg.

Evolution of animal synthesis

Ascorbic acid is a common enzymatic cofactor in mammals used in the synthesis of collagen, as well as a powerful reducing agent capable of rapidly scavenging a number of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Given that ascorbate has these important functions, it is surprising that the ability to synthesize this molecule has not always been conserved. In fact, anthropoid primates, Cavia porcellus (guinea pigs), teleost fishes, most bats, and some passerine birds have all independently lost the ability to internally synthesize vitamin C in either the kidney or the liver.[84][79] In all of the cases where genomic analysis was done on an ascorbic acid auxotroph, the origin of the change was found to be a result of loss-of-function mutations in the gene that encodes L-gulono-γ-lactone oxidase, the enzyme that catalyzes the last step of the ascorbic acid pathway outlined above.[85] One explanation for the repeated loss of the ability to synthesize vitamin C is that it was the result of genetic drift; assuming that the diet was rich in vitamin C, natural selection would not act to preserve it.[86][87]

In the case of the simians, it is thought that the loss of the ability to make vitamin C may have occurred much farther back in evolutionary history than the emergence of humans or even apes, since it evidently occurred soon after the appearance of the first primates, yet sometime after the split of early primates into the two major suborders

It has also been noted that the loss of the ability to synthesize ascorbate strikingly parallels the inability to break down uric acid, also a characteristic of primates. Uric acid and ascorbate are both strong reducing agents. This has led to the suggestion that, in higher primates, uric acid has taken over some of the functions of ascorbate.[92]

Plant synthesis

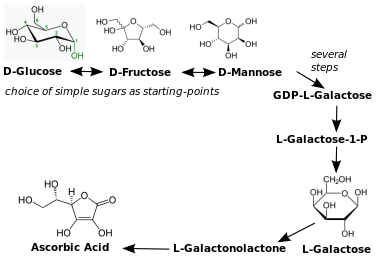

There are many different biosynthesis pathways to ascorbic acid in plants. Most proceed through products of glycolysis and other metabolic pathways. For example, one pathway utilizes plant cell wall polymers.[67] The principal plant ascorbic acid biosynthesis pathway seems to be via l-galactose. The enzyme l-galactose dehydrogenase catalyzes the overall oxidation to the lactone and isomerization of the lactone to the C4-hydroxyl group, resulting in l-galactono-1,4-lactone.[73] l-Galactono-1,4-lactone then reacts with the mitochondrial flavoenzyme l-galactonolactone dehydrogenase[93] to produce ascorbic acid.[73] l-Ascorbic acid has a negative feedback on l-galactose dehydrogenase in spinach.[94] Ascorbic acid efflux by embryos of dicot plants is a well-established mechanism of iron reduction and a step obligatory for iron uptake.[a]

All plants synthesize ascorbic acid. Ascorbic acid functions as a cofactor for enzymes involved in photosynthesis, synthesis of plant hormones, as an antioxidant and regenerator of other antioxidants.

Industrial synthesis

Vitamin C can be produced from

China produces about 70% of the global vitamin C market. The rest is split among European Union, India and North America. The global market is expected to exceed 141 thousand metric tons in 2024.[103] Cost per metric ton (1000 kg) in US dollars was $2,220 in Shanghai, $2,850 in Hamburg and $3,490 in the US.[104]

Medical uses

Vitamin C has a definitive role in treating scurvy, which is a disease caused by vitamin C deficiency. Beyond that, a role for vitamin C as prevention or treatment for various diseases is disputed, with reviews often reporting conflicting results. No effect of vitamin C supplementation reported for overall mortality.[105] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines and on the World Health Organization's Model Forumulary.[106] In 2021, it was the 255th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[107]

Scurvy

Notable human dietary studies of experimentally induced scurvy were conducted on conscientious objectors during World War II in Britain and on Iowa state prisoners in the late 1960s to the 1980s. Men in the prison study developed the first signs of scurvy about four weeks after starting the vitamin C-free diet, whereas in the earlier British study, six to eight months were required, possibly due to the pre-loading of this group with a 70 mg/day supplement for six weeks before the scorbutic diet was fed. Men in both studies had blood levels of ascorbic acid too low to be accurately measured by the time they developed signs of scurvy. These studies both reported that all obvious symptoms of scurvy could be completely reversed by supplementation of only 10 mg a day.[109][110] Treatment of scurvy can be with vitamin C-containing foods or dietary supplements or injection.[41][7]: 101

Sepsis

People in sepsis may have micronutrient deficiencies, including low levels of vitamin C.[111] An intake of 3.0 g/day, which requires intravenous administration, appears to be needed to maintain normal plasma concentrations in people with sepsis or severe burn injury.[112][113] Sepsis mortality is reduced with administration of intravenous vitamin C.[114][115]

Common cold

Research on vitamin C in the common cold has been divided into effects on prevention, duration, and severity. Oral intakes of more than 200 mg/day taken on a regular basis was not effective in prevention of the common cold. Restricting analysis to trials that used at least 1000 mg/day also saw no prevention benefit. However, taking a vitamin C supplement on a regular basis did reduce the average duration of the illness by 8% in adults and 14% in children, and also reduced the severity of colds.[116] Vitamin C taken on a regular basis reduced the duration of severe symptoms but had no effect on the duration of mild symptoms.[117] Therapeutic use, meaning that the vitamin was not started unless people started to feel the beginnings of a cold, had no effect on the duration or severity of the illness.[116]

Vitamin C distributes readily in high concentrations into immune cells, promotes natural killer cell activities, promotes lymphocyte proliferation, and is depleted quickly during infections, effects suggesting a prominent role in immune system function.[118] The European Food Safety Authority concluded there is a cause and effect relationship between the dietary intake of vitamin C and functioning of a normal immune system in adults and in children under three years of age.[119][120]

COVID-19

During March through July 2020, vitamin C was the subject of more US FDA warning letters than any other ingredient for claims for prevention and/or treatment of COVID-19.[121] In April 2021, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines stated that "there are insufficient data to recommend either for or against the use of vitamin C for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19."[122] In an update posted December 2022, the NIH position was unchanged:

- There is insufficient evidence for the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel (the Panel) to recommend either for or against the use of vitamin C for the treatment of COVID-19 in nonhospitalized patients.

- There is insufficient evidence for the Panel to recommend either for or against the use of vitamin C for the treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients.[123]

For people hospitalized with severe COVID-19 there are reports of a significant reduction in the risk of all-cause, in-hospital mortality with the administration of vitamin C relative to no vitamin C. There were no significant differences in ventilation incidence, hospitalization duration or length of intensive care unit stay between the two groups. The majority of the trials incorporated into these meta-analyses used intravenous administration of the vitamin.[124][125][126] Acute kidney injury was lower in people treated with vitamin C treatment. There were no differences in the frequency of other adverse events due to the vitamin.[126] The conclusion was that further large-scale studies are needed to affirm its mortality benefits before issuing updated guidelines and recommendations.[124][125][126]

Cancer

There is no evidence that vitamin C supplementation reduces the risk of lung cancer in healthy people or those at high risk due to smoking or asbestos exposure.[127] It has no effect on the risk of prostate cancer,[128] and there is no good evidence vitamic C supplementation affects the risk of colorectal cancer[129] or breast cancer.[130]

There is research investigating whether high dose intravenous vitamin C administration as a co-treatment will suppress cancer stem cells, which are responsible for tumor recurrence, metastasis and chemoresistance.[131][132]

Cardiovascular disease

There is no evidence that vitamin C supplementation decreases the risk cardiovascular disease,[133] although there may be an association between higher circulating vitamin C levels or dietary vitamin C and a lower risk of stroke.[134] There is a positive effect of vitamin C on endothelial dysfunction when taken at doses greater than 500 mg per day. (The endothelium is a layer of cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels.)[135]

Blood pressure

Serum vitamin C was reported to be 15.13 μmol/L lower in people with

Type 2 diabetes

There are contradictory reviews. From one, vitamin C supplementation cannot be recommended for management of type 2 diabetes.[139] However, another reported that supplementation with high doses of vitamin C can decrease blood glucose, insulin and hemoglobin A1c.[140]

Iron deficiency

One of the causes of iron-deficiency anemia is reduced absorption of iron. Iron absorption can be enhanced through ingestion of vitamin C alongside iron-containing food or supplements. Vitamin C helps to keep iron in the reduced ferrous state, which is more soluble and more easily absorbed.[141]

Topical application to prevent signs of skin aging

Human skin contains vitamin C, which supports collagen synthesis, decreases collagen degradation, and assists in antioxidant protection against UV-induced photo-aging, including photocarcinogenesis. This knowledge is often used as a rationale for the marketing of vitamin C as a topical "serum" ingredient to prevent or treat facial skin aging, melasma (dark pigmented spots) and wrinkles. The purported mechanism is that it functions as an antioxidant, neutralizing free radicals from sunlight exposure, air pollutants or normal metabolic processes.[142] The efficacy of topical treatment as opposed to oral intake is poorly understood.[143][144] The clinical trial literature is characterized as insufficient to support health claims; one reason being put forward was that "All the studies used vitamin C in combination with other ingredients or therapeutic mechanisms, thereby complicating any specific conclusions regarding the efficacy of vitamin C."[145] More research is needed.[146][clarification needed]

Cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease

Lower plasma vitamin C concentrations were reported in people with cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease compared to people with normal cognition.[147][148][149]

Eye health

Higher dietary intake of vitamin C was associated with lower risk of age-related cataracts.[150][151] Vitamin C supplementation did not prevent age-related macular degeneration.[152]

Periodontal disease

Low intake and low serum concentration were associated with greater progression of periodontal disease.[153][154]

Adverse effects

Oral intake as dietary supplements in excess of requirements are poorly absorbed,

There is a longstanding belief among the mainstream medical community that vitamin C increases risk of

There is extensive research on the purported benefits of intravenous vitamin C for treatment of sepsis,

History

Scurvy was known to Hippocrates, described in book two of his Prorrheticorum and in his Liber de internis affectionibus, and cited by James Lind.[162] Symptoms of scurvy were also described by Pliny the Elder: (i) Pliny. "49". Naturalis historiae. Vol. 3.; and (ii) Strabo, in Geographicorum, book 16, cited in the 1881 International Encyclopedia of Surgery.[163]

Scurvy at sea

In the 1497 expedition of Vasco da Gama, the curative effects of citrus fruit were known.[164] In the 1500s, Portuguese sailors put in to the island of Saint Helena to avail themselves of planted vegetable gardens and wild-growing fruit trees.[165] Authorities occasionally recommended plant food to prevent scurvy during long sea voyages. John Woodall, the first surgeon to the British East India Company, recommended the preventive and curative use of lemon juice in his 1617 book, The Surgeon's Mate.[166] In 1734, the Dutch writer Johann Bachstrom gave the firm opinion, "scurvy is solely owing to a total abstinence from fresh vegetable food, and greens."[167][168] Scurvy had long been a principal killer of sailors during the long sea voyages.[169] According to Jonathan Lamb, "In 1499, Vasco da Gama lost 116 of his crew of 170; In 1520, Magellan lost 208 out of 230; ... all mainly to scurvy."[170]

The first attempt to give scientific basis for the cause of this disease was by a ship's surgeon in the Royal Navy, James Lind. While at sea in May 1747, Lind provided some crew members with two oranges and one lemon per day, in addition to normal rations, while others continued on cider, vinegar, sulfuric acid or seawater, along with their normal rations, in one of the world's first controlled experiments.[171] The results showed that citrus fruits prevented the disease. Lind published his work in 1753 in his Treatise on the Scurvy.[172]

Fresh fruit was expensive to keep on board, whereas boiling it down to juice allowed easy storage, but destroyed the vitamin (especially if it was boiled in copper kettles).[39] It was 1796 before the British navy adopted lemon juice as standard issue at sea. In 1845, ships in the West Indies were provided with lime juice instead, and in 1860 lime juice was used throughout the Royal Navy, giving rise to the American use of the nickname "limey" for the British.[171] Captain James Cook had previously demonstrated the advantages of carrying "Sour krout" on board by taking his crew on a 1772-75 Pacific Ocean voyage without losing any of his men to scurvy.[173] For his report on his methods the British Royal Society awarded him the Copley Medal in 1776.[174]

The name antiscorbutic was used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for foods known to prevent scurvy. These foods included lemons, limes, oranges, sauerkraut, cabbage, malt, and portable soup.[175] In 1928, the Canadian Arctic anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson showed that the Inuit avoided scurvy on a diet largely of raw meat. Later studies on traditional food diets of the Yukon First Nations, Dene, Inuit, and Métis of Northern Canada showed that their daily intake of vitamin C averaged between 52 and 62 mg/day.[176]

Discovery

Vitamin C was discovered in 1912, isolated in 1928 and synthesized in 1933, making it the first vitamin to be synthesized.

In 1907, a laboratory animal model which would help to identify the antiscorbutic factor was discovered by the Norwegian physicians

From 1928 to 1932,

In 1957, J. J. Burns showed that some mammals are susceptible to scurvy as their liver does not produce the enzyme l-gulonolactone oxidase, the last of the chain of four enzymes that synthesize vitamin C.[191][192] American biochemist Irwin Stone was the first to exploit vitamin C for its food preservative properties. He later developed the idea that humans possess a mutated form of the l-gulonolactone oxidase coding gene.[193] Stone introduced Linus Pauling to the theory that humans needed to consume vitamin C in quantities far higher than what was considered a recommended daily intake in order to optimize health.[194]

In 2008, researchers discovered that in humans and other primates the red blood cells have evolved a mechanism to more efficiently utilize the vitamin C present in the body by recycling oxidized l-dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) back into ascorbic acid for reuse by the body. The mechanism was not found to be present in mammals that synthesize their own vitamin C.[195]

History of large dose therapies

Vitamin C megadosage is a term describing the consumption or injection of vitamin C in doses comparable to or higher than the amounts produced by the livers of mammals which are able to synthesize vitamin C. An argument for this, although not the actual term, was described in 1970 in an article by Linus Pauling. Briefly, his position was that for optimal health, humans should be consuming at least 2,300 mg/day to compensate for the inability to synthesize vitamin C. The recommendation also fell into the consumption range for gorillas — a non-synthesizing near-relative to humans.[82] A second argument for high intake is that serum ascorbic acid concentrations increase as intake increases until it plateaus at about 190 to 200 micromoles per liter (µmol/L) once consumption exceeds 1,250 milligrams.[196] As noted, government recommendations are a range of 40 to 110 mg/day and normal plasma is approximately 50 µmol/L, so "normal" is about 25% of what can be achieved when oral consumption is in the proposed megadose range.

Pauling popularized the concept of high dose vitamin C as prevention and treatment of the common cold in 1970. A few years later he proposed that vitamin C would prevent cardiovascular disease, and that 10 grams/day, initially administered intravenously and thereafter orally, would cure late-stage cancer.[197] Mega-dosing with ascorbic acid has other champions, among them chemist Irwin Stone[194] and the controversial Matthias Rath and Patrick Holford, who both have been accused of making unsubstantiated treatment claims for treating cancer and HIV infection.[198][199] The idea that large amounts of intravenous ascorbic acid can be used to treat late-stage cancer or ameliorate the toxicity of chemotherapy is — some forty years after Pauling's seminal paper — still considered unproven and still in need of high quality research.[200][201][158]

Notes

References

- ^ "Ascorbic acid injection 500mg/5ml". (emc). July 15, 2015. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Ascorbic acid 100mg tablets". (emc). October 29, 2018. Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Ascor- ascorbic acid injection". DailyMed. October 2, 2020. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Vitamin C: Fact sheet for health professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. March 26, 2021. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "Vitamin C". Chem Spider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Vitamin C". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. July 1, 2018. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-66162-1.

- ^ "Testing foods for vitamin C (ascorbic acid)" (PDF). British Nutrition Foundation. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 23, 2015.

- ^ "Measuring the vitamin C content of foods and fruit juices". Nuffield Foundation. November 24, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015.

- ^ PMID 19675106.

- PMC 8180804.

- PMID 32640674.

- PMID 15820776.

- ^ "Dietary guidelines for Indians" (PDF). National Institute of Nutrition, India. 2011. p. 90. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ISBN 978-92-4-154612-6.

- ^ "Commission Directive 2008/100/EC of 28 October 2008 amending Council Directive 90/496/EEC on nutrition labeling for foodstuffs as regards recommended daily allowances, energy conversion factors and definitions". The Commission of the European Communities. October 29, 2008. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016.

- ^ "Vitamin C". Natural Health Product Monograph. Health Canada. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "Overview of dietary reference intakes for Japanese" (PDF). Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Japan). 2015. p. 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ .

- PMID 25145261.

- ^ "TABLE 1: Nutrient intakes from food and beverages" (PDF). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: What We Eat in America, DHHS-USDA Dietary Survey Integration. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2017.

- ^ "TABLE 37: Nutrient intakes from dietary supplements" (PDF). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: What We Eat in America, DHHS-USDA Dietary Survey Integration. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Tolerable upper intake levels for vitamins and minerals" (PDF). European Food Safety Authority. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2016.

- ^ "Federal Register May 27, 2016 food labeling: Revision of the nutrition and supplement facts labels. FR page 33982" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2016.

- ^ "Daily Value Reference of the Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD)". Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD). Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ REGULATION (EU) No 1169/2011 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL Archived July 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Official Journal of the European Union. page 304/61. (2009).

- ^ "NDL/FNIC food composition database home page". USDA Nutrient Data Laboratory, the Food and Nutrition Information Center and Information Systems Division of the National Agricultural Library. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c "USDA national nutrient database for standard reference legacy: vitamin C" (PDF). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Brand JC, Rae C, McDonnell J, Lee A, Cherikoff V, Truswell AS (1987). "The nutritional composition of Australian aboriginal bushfoods. I". Food Technology in Australia. 35 (6): 293–6.

- PMID 11464674.

- .

- ISBN 978-81-207-3714-3.

- ISBN 978-1-118-35263-2.

- PMID 19021790.

- ^ Clark S (January 8, 2007). "Comparing milk: human, cow, goat & commercial infant formula". Washington State University. Archived from the original on January 29, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- PMID 7621082.

- PMID 14801407.

- ^ Oxford University. October 9, 2005. Archivedfrom the original on February 9, 2007. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Introduction". Vitamin C fortification of food aid commodities: final report. National Academies Press (US). 1997. Archived from the original on January 21, 2024. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Ascorbic acid (Monograph)". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- PMID 27375360.

- ^ "Why fortify?". Food Fortification Initiative. December 2023. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ a b "Map: Count of nutrients in fortification standards". Global Fortification Data Exchange. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "USAID's Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance website". November 21, 2023.

- ^ Washburn C, Jensen C (2017). "Pretreatments to prevent darkening of fruits prior to canning or dehydrating". Utah State University. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ "Ingredients". The Federation of Bakers. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions | why food additives". Food Additives and Ingredients Association UK & Ireland- Making life taste better. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e UK Food Standards Agency: "Approved additives and their E numbers". Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c US Food and Drug Administration:"Listing of food additives status part I". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Health Canada "List of permitted preservatives (lists of permitted food additives) - Government of Canada". Government of Canada. November 27, 2006. Archived from the original on October 27, 2022. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code"Standard 1.2.4 – labeling of ingredients". September 8, 2011. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ "Listing of food additives status part II". US Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on November 8, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- PMID 34717701.

- PMID 29971019.

- S2CID 81981938.

- PMID 31601028.

- ^ S2CID 312905.

- PMID 9228080.

- ^ S2CID 21345196.

- PMID 12729925.

- ^ PMID 26808119.

- PMID 17971855.

- S2CID 4421568.

- ^ a b c Stone I (1972). "The natural history of ascorbic acid in the evolution of the mammals and primates and is significance for present-day man evolution of mammals and primates" (PDF). Journal of Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 1 (2): 82–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- S2CID 20139913.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- PMID 1962571.

- PMID 1400507.

- PMID 10572964.

- PMID 11666145.

- S2CID 1674389.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-74167-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4557-7399-2. Archivedfrom the original on December 7, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- .

- PMID 21037206.

- PMID 22069493.

- JSTOR 4089257.

- ^ PMID 22294879.

- ISBN 978-0-226-04443-9.

- (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2017.

- ^ PMID 5275366.

- ^ Parrott T (October 2022). "Nutritional diseases of nonhuman primates". Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on December 24, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- S2CID 7747147.

- S2CID 14393449.

- PMID 20210993.

- PMID 3338984.

- ^ PMID 3113259.

- PMID 15085543.

- S2CID 23525774.

- S2CID 1851788.

- S2CID 4146946.

- S2CID 25096297.

- PMID 15509850.

- PMID 24347170.

- ^ PMID 24278786.

- ^ PMID 28744455.

- PMID 27179323.

- PMID 23208776.

- ^ "The production of vitamin C" (PDF). Competition Commission. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 19, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- PMID 33717042.

- PMID 35996146.

- ^ "Vantage market research: global vitamin C market size & share to surpass $1.8 Bn by 2028". Globe Newswire (Press release). November 8, 2022. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ "Vitamin C price trend and forecast". ChemAnalyst. September 2023. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- PMID 22419320.

- ISBN 978-92-4-154765-9.

- ^ "Ascorbic acid - drug usage statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- PMID 21402244.

- PMID 4977512.

- PMID 16510534.

- S2CID 51599526.

- ^ PMID 36915173.

- S2CID 37895257.

- PMID 37111066.

- PMID 37599680.

- ^ PMID 23440782.

- PMID 38082300.

- (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- .

- hdl:11380/1296052.

- PMID 33001378.

- ^ "Vitamin C". COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. April 21, 2021. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "COVID-19 treatment guidelines". U.S. National Institutes of Health. December 26, 2022. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ PMID 37071316.

- ^ PMID 36553979.

- ^ PMID 36235869.

- PMID 32130738.

- PMID 21273283.

- S2CID 44706004.

- S2CID 24867472.

- PMID 38067361.

- PMID 31947879.

- PMID 28301692.

- PMID 24284213.

- PMID 24792921.

- PMID 32426036.

- ^ PMID 32080138.

- from the original on January 21, 2024. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- from the original on January 21, 2024. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- S2CID 259581695.

- PMID 28189173.

- ^ Nathan N, Patel P (November 10, 2021). "Why is topical vitamin C important for skin health?". Harvard Health Publishing, Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on October 14, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- PMID 28805671.

- PMID 29104718.

- PMID 37683066. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2024 (link - S2CID 258439047.

- PMID 24144963.

- PMID 22543848.

- PMID 22366772.

- S2CID 81981938.

- PMID 30624584.

- PMID 28756617.

- PMID 38245765.

- PMID 31336735.

- PMID 9818798.

- (PDF) from the original on September 18, 2012.

- PMID 23381591.

- ^ PMID 25601965.

- PMID 34684565.

- PMID 34833042.

- PMID 33113146.

- ^ Lind J (1772). A Treatise on the Scurvy (3rd ed.). London, England: G. Pearch and W. Woodfall. p. 285. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ Ashhurst J, ed. (1881). The International Encyclopedia of Surgery. Vol. 1. New York, New York: William Wood and Co. p. 278. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016.

- PMID 11581484. Archived from the originalon September 4, 2015.

As they sailed farther up the east coast of Africa, they met local traders, who traded them fresh oranges. Within six days of eating the oranges, da Gama's crew recovered fully

- ^ Livermore H (2004). "Santa Helena, a forgotten Portuguese discovery" (PDF). Estudos Em Homenagem a Luis Antonio de Oliveira Ramos [Studies in Homage to Luis Antonio de Oliveira Ramos.]: 623–631. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2011.

On returning, Lopes' ship had left him on St Helena, where with admirable sagacity and industry he planted vegetables and nurseries with which passing ships were marvelously sustained. [...] There were 'wild groves' of oranges, lemons and other fruits that ripened all the year round, large pomegranates and figs.

- ^ Woodall J (1617). The Surgion's Mate. London, England: Edward Griffin. p. 89. Archived from the original on April 11, 2016.

Succus Limonum, or juice of Lemons ... [is] the most precious help that ever was discovered against the Scurvy[;] to be drunk at all times; ...

- ^ Armstrong A (1858). "Observation on naval hygiene and scurvy, more particularly as the later appeared during the Polar voyage". British and Foreign Medico-chirurgical Review: Or, Quarterly Journal of Practical Medicine and Surgery. 22: 295–305.

- ^ Bachstrom JF (1734). Observationes circa scorbutum [Observations on scurvy] (in Latin). Leiden (Lugdunum Batavorum), Netherlands: Conrad Wishof. p. 16. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

... sed ex nostra causa optime explicatur, que est absentia, carentia & abstinentia a vegetabilibus recentibus, ... ( ... but [this misfortune] is explained very well by our [supposed] cause, which is the absence of, lack of, and abstinence from fresh vegetables, ...

- ^ Lamb J (February 17, 2011). "Captain Cook and the scourge of scurvy". British History in depth. BBC. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-226-46849-5. Archivedfrom the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ S2CID 20435128.

- ^ Lind J (1753). A treatise of the scurvy. London: A. Millar. In the 1757 edition of his work, Lind discusses his experiment starting on "A treatise of the scurvy". p. 149. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-14-043647-1.

- ^ "Copley Medal, past winners". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ISBN 978-1-74114-200-6.

- PMID 15173410.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84826-195-2. Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- PMID 356548.

- ^ "Redoxon trademark information by Hoffman-la Roche, Inc. (1934)". Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ISBN 978-3-527-33734-7.

- PMID 12555613.

- PMID 9105273.

- ^ S2CID 11077461.

- ^ PMID 16744896.

- PMID 11963399.

- PMID 4589872.

- PMID 4612454.

- ^ a b "The Albert Szent-Gyorgyi Papers: Szeged, 1931-1947: Vitamin C, Muscles, and WWII". Profiles in Science. United States National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on May 5, 2009.

- ^ "Scurvy". Online Entymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- PMID 15416703.

- from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- PMID 13380431.

- from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Saul A. "Orthomolecular Medicine Hall of fame - Irwin Stone, Ph.D." Orthomolecular Organization. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- S2CID 18128118.

- PMID 19508394.

- PMID 1068480.

- ^ Boseley S (September 12, 2008). "Fall of the vitamin doctor: Matthias Rath drops libel action". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Colquhoun D (August 15, 2007). "The age of endarkenment | Science | guardian.co.uk". Guardian. Archived from the original on March 6, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Barret S (September 14, 2014). "The dark side of Linus Pauling's legacy". www.quackwatch.org. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.[unreliable source?]

- S2CID 206983069.