Vitus Bering

This article's lead section may be too long. (February 2024) |

Vitus Bering | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Vitus Jonassen Bering |

| Born | 5 August 1681 Horsens, Denmark–Norway |

| Died | 19 December 1741 (aged 60) Bering Island, Bering Sea |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Service years | 1704–1741 |

| Expeditions |

|

Vitus Jonassen Bering (Danish: [ˈviːtsʰus ˈjoːnæsn̩ ˈpe̝(ː)ɐ̯e̝ŋ]; baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),[1][nb 1] also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering (Russian: Иван Иванович Беринг),[2] was a Danish cartographer and explorer in Russian service, and an officer in the Russian Navy. He is known as a leader of two Russian expeditions, namely the First Kamchatka Expedition and the Great Northern Expedition, exploring the north-eastern coast of the Asian continent and from there the western coast on the North American continent. The Bering Strait, the Bering Sea, Bering Island, the Bering Glacier, and Vitus Lake were all named in his honor.

Taking to the seas as a ship's boy at the age of 15, Bering travelled extensively over the next eight years, as well as taking naval training in Amsterdam. In 1704, he enrolled with the rapidly expanding Russian Navy of Tsar Peter I. After serving with the navy in significant but non-combat roles during the Great Northern War, Bering resigned in 1724 to avoid the continuing embarrassment of his low rank to his wife; and upon retirement was promoted to first captain. Bering was permitted to keep the rank as he rejoined the Russian Navy later the same year.

He was selected by the Tsar to captain the First Kamchatka Expedition, an expedition set to sail north from Russian outposts on the

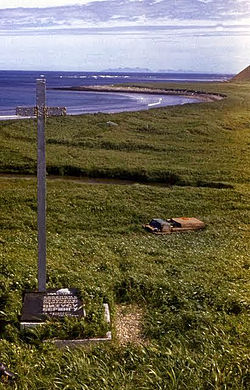

Having returned to Okhotsk with a much larger, better prepared, and much more ambitious expedition, Bering set off for an expedition towards North America in 1741. While doing so, the expedition spotted Mount Saint Elias, and sailed past Kodiak Island. A storm separated the ships, but Bering sighted the southern coast of Alaska, and a landing was made at Kayak Island or in the vicinity. Adverse conditions forced a return, but he documented some of the Aleutian Islands on his way back. One of the sailors died and was buried on one of these islands, and Bering named the island group Shumagin Islands after him. Bering himself became too ill to command his ship, which was at last driven to seek refuge on an uninhabited island in the Commander Islands group in the southwest Bering Sea. On 19 December 1741, Bering died on the island, which was given the name Bering Island after him, near the Kamchatka Peninsula, reportedly from scurvy, along with 28 men of his company.[nb 2]

Biography

Early life

Vitus Bering was born in the port town of

On 8 October 1713, Bering married Anna Christina Pülse; the ceremony took place in the Lutheran church at Vyborg, only recently annexed from Sweden. Over the next 18 years, they had nine children, four of whom survived childhood.[5] During his time with the Russian navy – particularly as part of the Great Northern War – he was unable to spend much time with Anna, who was approximately eleven years Bering's junior and the daughter of a Swedish merchant. At the war's conclusion in 1721, Bering was not promoted like many of his contemporaries.[5] The omission proved particularly embarrassing when, in 1724, Anna's younger sister Eufemia upstaged her by marrying Thomas Saunders, already a rear-admiral despite a much shorter period of service. In order to save face, the 42-year-old Bering decided to retire from the navy, securing two months' pay and a notional promotion to first captain. Shortly after, the family – Bering, his wife Anna, and two young sons – moved out of St. Petersburg to live with Anna's family in Vyborg. After a period of joblessness lasting five months, however, Bering (keenly aware of his dependents), decided to reapply to the Admiralty. He was accepted for a renewed period of active service the same day.[5] By 2 October 1724, Bering (retaining the rank of first captain he had secured earlier in the year) was back on the sea, commanding the ninety-gun Lesnoe (Russian: Лесное, "Forest"). The Tsar would soon have a new command for him, however.[4]

First Kamchatka expedition

St. Petersburg to Okhotsk

On 29 December 1724 [

Both parties used horse-drawn sledges and made good time over the first legs of the journey. On 14 February they were reunited in Vologda, and, now travelling together, headed eastwards across the

After leaving Ust-Kut when the river ice melted in the spring of 1726, the party rapidly travelled down the River Lena, reaching Yakutsk in the first half of June. Despite the need for hurry and men being sent in advance, the governor was slow to grant them the resources they needed, prompting threats from Bering. On 7 July, Spanberg left with a detachment of 209 men and much of the cargo; on 27 July apprentice shipbuilder Fyodor Kozlov led a small party to reach Okhotsk ahead of Spanberg, both to prepare food supplies and to start work repairing the Vostok and building a new ship, the Fortuna (

Okhotsk to Kamchatka and beyond

The Vostok was readied and the Fortuna built at a rapid pace, with the first party (48 men commanded by Spanberg and comprising those required to start work on the ships that would have to be built in Kamchatka itself as soon as possible) leaving in June 1727. Chirikov himself arrived in Okhotsk soon after, bringing further supplies of food. He had had a relatively easy trip, losing none of his men and only 17 of the 140 horses he had set out with. On 22 August, the remainder of the party sailed for Kamchatka.

Reaching a cape (which Chirikov named

Second Kamchatka expedition and death

Preparations

Bering soon proposed a second Kamchatka expedition, much more ambitious than the first and with an explicit aim of sailing east in search of North America. The political situation in the Russian Empire was difficult, however, and this meant delays. In the interim, the Berings enjoyed their new-found status and wealth: there was a new house and a new social circle for the newly ennobled Berings. Bering also made a bequest to the poor of Horsens, had two children with Anna and even attempted to establish his familial coat of arms.[13] The proposal, when it was accepted, would a significant affair, which involved 600 people from the outset and several hundred added along the way.[14] Though Bering seems to have been primarily interested in landing in North America, he recognised the importance of secondary objectives: the list of which expanded rapidly under the guidance of planners Nikolai Fedorovich Golovin (head of the Admiralty); Ivan Kirilov, a highly ranked politician with an interest in geography, and Andrey Osterman, a close adviser of the new Empress, Anna Ivanovna. As Bering waited for Anna to solidify her grip on the throne, he and Kirilov worked to find a new, more dependable administrator to run Okhotsk and to begin work on improving the roads between Yakutsk and the coastal settlement. Their choice for the post of administrator, made remotely, was Grigory Skornyakov-Pisarev; possibly the least bad candidate, he would nevertheless turn out to be a poor choice. In any case, Skornyakov-Pisarev was ordered in 1731 to proceed to Okhotsk, with directions to expand it into a proper port. He did not leave for Okhotsk for another four years, by which time Bering's own expedition (in time for which Okhotsk was supposed to have been prepared) was not far off.[13]

In 1732, however, Bering was still at the planning stage in Moscow, having taken a short leave of absence for St. Petersburg. The better positioned Kirilov oversaw developments, eyeing up not only the chance of discovering North America, but of mapping the whole Arctic coast, finding a good route south to Japan, landing on the

St. Petersburg to Kamchatka

Spanberg left St. Petersburg in February 1733 with the first (small) detachment of the second expedition, bound for Okhotsk. Chirikov followed on 18 April with the main contingent (initially 500 people and eventually swelling to approximately 3000 after labourers were added). Following them, on 29 April Bering followed with Anna and their two youngest children – their two eldest, both sons, were left with friends in

At Okhotsk things were little better; it was "ill-suited to be a permanent port", and Skornyakov-Pisarev was slow to construct the buildings needed. Spanberg was, however, able to ready the ships the expedition needed. By the end of 1737 the St. Gabriel had been refitted; additionally, two new ships—the Archangel Michael (Архангел Михаил, Arkhangel Mikhail) and the Nadezhda (Надежда)—had been constructed and were rapidly readied for a voyage to Japan, a country with which Russia had never had contact. The same year, Bering took up residence in Okhotsk. It was the fifth year of the expedition, and the original costings now looked naive compared to the true costs of the trip. The additional costs (300,000 roubles compared to the 12,000 budgeted) brought poverty to the whole region. On 29 June 1738, Spanberg set off for the Kuril Islands with the three ships he had prepared. After he had left there were further delays, probably due to a lack of natural resources. Over the next three years, Bering himself was criticised on an increasingly regular basis (his salary had already been halved in 1737 when the originally planned four years ran out); the delays also caused friction between Bering, Chirikov (who felt unduly constrained) and Spanberg (who felt Bering was too weak in his dealings with the local peoples). The two key figures who had been so useful to Bering in St. Petersburg back in the early 1730s (Saunders and Kirilov) were now dead, and there were occasional moves to either terminate the expedition or to replace Bering. Meanwhile, a fourth ship, the Bolsheretsk (Большерецк) was constructed and Spanberg (having identified some 30 Kuril Islands on his first trip) led the four ships on a second voyage, which saw the first Russians land in Japan. In August 1740, with the main, America-bound expedition almost ready, Anna Bering returned to St. Petersburg with her and Vitus' younger children. Bering would never see his wife again.[18] Those without places on a ship also began the long journey home. As they left, a messenger arrived; the admiralty was demanding a progress update. Bering delayed, promising a partial report from Spanberg and a fuller report later.[19]

Sea voyage, death and achievements

With time now of the essence, the Okhotsk (Охотск) left for Bolsheretsk, arriving there in mid-September. Another new ship, the St. Peter (Святой Пётр, Sviatoi Piotr, Pyotr, or Pëtr), captained by Bering, also left. It was accompanied by its sister creation the St. Paul (Святой Павел, Sviatoi Pavel) and the Nadezhda. Delayed by the Nadezhda's hitting a sand bank and then being beaten by a storm, such that it was forced to stay at Bolsheretsk, the two other ships arrived in their destination of

The expedition spotted the volcano

Assessing the scale of Bering's achievements is difficult, given that he was neither the first Russian to sight North America (that having been achieved by

See also

- Exploration of the Pacific

- Russian America

- Second Kamchatka expedition

Notes

- ^ All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time.

- ^ a b The 1991 Russian-Danish expedition that exhumed Bering's remains also analyzed teeth and bones and concluded that he did not die from scurvy. Based on analyses made in Moscow and on Steller's original report, heart failure was the likely cause of death (Frost 2003).

- ^ In 1991 a Russian-Danish expedition found Bering's burial site. Analysis of Bering's skull also showed that Bering could not have had such a round face, as is depicted in most pictures. The analysis showed a man of strong stature and a more angular face. The portrait most frequently attributed to Bering may possibly be the writer Vitus Pedersen Bering, who was Bering's uncle.

References

Citations

- ^ Frost 2003, pp. xx–xxi

- ^ a b c d e f Armstrong 1982, p. 161

- ^ a b c d e Frost 2003, pp. 19–22

- ^ a b Frost 2003, pp. 29–31

- ^ a b c d Frost 2003, pp. 26–28

- ^ a b c d e Frost 2003, pp. 30–40

- ^ Epishkin, Sergey. "Vitus Bering. Question of biography" (in Russian). Kamchatsky region science lubrary. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ ПУЛЕНКОВА, Юлианна. КАМЧАТСКИЕ ЭКСПЕДИЦИИ [KAMCHATKA EXPEDITIONS] (PDF) (in Russian). Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ a b Frost 2003, pp. 41–44

- ^ a b c Frost 2003, pp. 44–47

- ^ a b c Frost 2003, pp. 48–55

- ^ a b Frost 2003, pp. 56–62

- ^ a b c d e f g Frost 2003, pp. 63–73

- ^ Egerton 2008

- ^ Debenham 1941, p. 421

- ^ Armstrong 1982, p. 163

- ^ a b c Frost 2003, pp. 74–81

- ^ a b Frost 2003, pp. 84–92

- ^ a b Frost 2003, pp. 112–120

- ^ Frost 2003, pp. 237–245

- ^ Frost 2003, p. 7

- ^ Frost 2003, pp. 246–269

- ^ Armstrong 1982, pp. 162–163

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Terence (1982), "Vitus Bering", Polar Record, 21 (131), United Kingdom: 161–163, S2CID 251063437

- Debenham, Frank (1941), "Bering's last Voyage", Polar Record, 3 (22), United Kingdom: 421–426, S2CID 129168535

- Frost, Orcutt William, ed. (2003), Bering: The Russian Discovery of America, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10059-0

- Lauridsen, Peter (1885), Bering og de Russiske Opdagelsesrejser (in Danish), Copenhagen

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Müller, Gerhard Friedrich (1758), Sammlung russischer Geschichten (in German), vol. iii, St Petersburg: Kayserl. Academie der Wißenschafften

- Oliver, James A. (2006), The Bering Strait Crossing, United Kingdom: Information Architects, ISBN 978-0-9546995-7-4

- Lind, Natasha Okhotina; Møller, Peter Ulf, eds. (2002), Under Vitus Bering's Command: New Perspectives on the Russian Kamchatka Expeditions, Beringiana, Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, ISBN 87-7288-932-2

- Egerton, Frank N. (2008), "A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 27: Naturalists Explore Russia and the North Pacific During the 1700s", Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 89 (1): 39–60,

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 775. This further cites:

- G. F. Müller, Sammlung russischer Geschichten, vol. iii. (St Petersburg, 1758)

- P. Lauridsen, Bering og de Russiske Opdagelsesrejser (Copenhagen, 1885).