Volcanology

Volcanology (also spelled vulcanology) is the study of

of fire.A

Modern volcanology

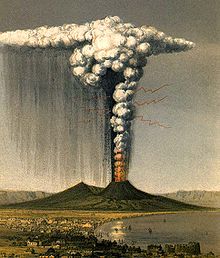

In 1841, the first volcanological observatory, the Vesuvius Observatory, was founded in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.[1] Volcanology advances have required more than just structured observation, and the science relies upon the understanding and integration of knowledge in many fields including geology, tectonics, physics, chemistry and mathematics, with many advances only being able to occur after the advance had occurred in another field of science. For example the study of radioactivity only commenced in 1896,[2] and its application to the theory of plate tectonics and radiometric dating took about 50 years after this. Many other developments in fluid dynamics, experimental physics and chemistry, techniques of mathematical modelling, instrumentation and in other sciences have been applied to volcanology since 1841.

Techniques

Seismic observations are made using

Surface

Gas emissions may be monitored with equipment including portable ultra-violet spectrometers (COSPEC, now superseded by the miniDOAS), which analyzes the presence of volcanic gases such as sulfur dioxide; or by infra-red spectroscopy (FTIR). Increased gas emissions, and more particularly changes in gas compositions, may signal an impending volcanic eruption.[3]

Temperature changes are monitored using thermometers and observing changes in thermal properties of volcanic lakes and vents, which may indicate upcoming activity.[5]

Other geophysical techniques (electrical, gravity and magnetic observations) include monitoring fluctuations and sudden change in resistivity, gravity anomalies or magnetic anomaly patterns that may indicate volcano-induced faulting and magma upwelling.[5]

Stratigraphic analyses includes analyzing tephra and lava deposits and dating these to give volcano eruption patterns,[8] with estimated cycles of intense activity and size of eruptions.[3]

Compositional analysis has been very successful in the grouping of volcanoes by type,[9]: 274 origin of magma,[9]: 274 including matching of volcanoes to a mantle plume of a particular hotspot, mantle plume melting depths,[10] the history of recycled subducted crust,[9]: 302–3 matching of tephra deposits to each other and to volcanoes of origin,[11] and the understanding the formation and evolution of magma reservoirs,[9]: 296–303 an approach which has now been validated by real time sampling.[12]

Forecasting

Some of the techniques mentioned above, combined with modelling, have proved useful and successful in the forecasting of some eruptions,[13]: 1–2 such as the evacuation of the locality around Mount Pinatubo in 1991 that may have saved 20,000 lives.[14] Short-term forecasts tend to use seismic or multiple monitoring data with long term forecasting involving the study of the previous history of local volcanism.[13]: 1 However, volcanology forecasting does not just involve predicting the next initial onset time of an eruption, as it might also address the size of a future eruption, and evolution of an eruption once it has begun.[13]: 1–2

History

Volcanology has an extensive history. The earliest known recording of a volcanic eruption may be on a wall painting dated to about 7,000 BCE found at the

Greco-Roman philosophy

The classical world of Greece and the early

The Greek philosopher Empedocles (c. 490-430 BCE) saw the world divided into four elemental forces, of Earth, Air, Fire and Water. Volcanoes, Empedocles maintained, were the manifestation of Elemental Fire. Plato contended that channels of hot and cold waters flow in inexhaustible quantities through subterranean rivers. In the depths of the earth snakes a vast river of fire, the Pyriphlegethon, which feeds all the world's volcanoes. Aristotle considered underground fire as the result of "the...friction of the wind when it plunges into narrow passages."

Wind played a key role in volcano explanations until the 16th century after

Renaissance observations

The Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) witnessed eruptions of Mount Etna and Stromboli, then visited the crater of Vesuvius and published his view of an Earth with a central fire connected to numerous others caused by the burning of sulfur, bitumen and coal. He published his view of this in Mundus Subterraneus with volcanoes acting as a type of safety valve.[20]

Science wrestled with the ideas of the combustion of pyrite with water, that rock was solidified bitumen, and with notions of rock being formed from water (Neptunism). Of the volcanoes then known, all were near the water, hence the action of the sea upon the land was used to explain volcanism.

Interaction with religion and mythology

Tribal legends of

In 1660 the eruption of Vesuvius rained

Notable volcanologists

- Plato (428–348 BC)

- Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD)

- Pliny the Younger (61 – c. 113 AD)

- George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788)

- James Hutton (1726–1797)

- Déodat Gratet de Dolomieu (1750–1801)

- George Julius Poulett Scrope (1797–1876)

- Giuseppe Mercalli (1850–1914)

- Thomas Jaggar (1871–1953), founder of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory

- French Government and Jacques Cousteau

- George P. L. Walker (1926–2005), pioneering volcanologist who transformed the subject into a quantitative science

- Haraldur Sigurdsson(born 1939), Icelandic volcanologist and geochemist

- Katia and Maurice Krafft (1942–1991 and 1946–1991, respectively), died at Mount Unzen in Japan, 1991

- David A. Johnston (1949–1980), killed during the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens

- Harry Glicken (1958–1991), died at Mount Unzen in Japan, 1991

Gallery

-

Arenal Volcano, Costa Rica at night.

-

Krýsuvík, a thermal area in the Southwest of Iceland.

-

Sulphur deposit at Halemaʻumaʻu on Kīlaueain Big Island, Hawaii

-

Erosional dissection of an ash deposit at Pinatubo volcano in the Philippines.

-

The eruption of the geysir Strokkur in early morning.

See also

- Global Volcanism Program

- GNS Science (formerly the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences) (in New Zealand)

- Igneous rock

- Important publications in volcanology

- Kiyoo Mogi, developer of the Mogi model of volcano deformation

- Tephrochronology

- Volcano

- Volcano Number

- Volcanism

References

- INGV, accessed 29 August 2016.

- ^ Becquerel, Henri (1896). "Sur les radiations invisibles émises par les corps phosphorescents". Comptes Rendus. 122: 501–503.

- ^ ISBN 0-7167-8929-9

- ^ Bartel, B., 2002. Magma dynamics at Taal Volcano, Philippines from continuous GPS measurements. Master's Thesis, Department of Geological Sciences, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana

- ^ ISBN 0-19-925469-9

- ^ "Archive: NASA Observes Ash Plume of Icelandic Volcano". NASA.

- ^ "NASA ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer), Volcanology". Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

- ISSN 1525-2027.

- ^ .

- .

- hdl:10289/11352.

- hdl:10447/576270.: Main

- ^ hdl:10356/137220.

- ^ Pappas, Stephanie (15 June 2011). "Pinatubo: Why the Biggest Volcanic Eruption Wasn't the Deadliest". LiveScience. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ISBN 9781315425177.

- ^ Meece, Stephanie, (2006)A bird’s eye view - of a leopard’s spots. The Çatalhöyük ‘map’ and the development of cartographic representation in prehistory Anatolian Studies 56:1-16. See http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/195777

- ^ Ülkekul, Cevat, (2005)Çatalhöyük Şehir Plani: Town Plan of Çatalhöyük Dönence, Istanbul.

- .

- ^ ISBN 9780123859396.

- ^ Major, RH (1939). "Athanasius Kircher" (PDF). Annals of Medical History. 1 (2): 105-20. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Williams, Micheal (November 2007). "Hearts of fire". Morning Calm (11–2007): 6.

- S2CID 129186824.

- ^ Ngāwhare-Pounamu, D. "Living Memory and the Travelling Mountain Narrative of Taranaki" (PDF). Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-6347-3.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-86716-887-7

- ^ Kirsch, Johann Peter. "St. Agatha." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 25 April 2013

- ^ Volcanoes: Crucibles of Change Richard V. Fisher, Grant Heiken, Jeffrey B. Hulen Princeton University Press, 1998

- ^ Festa: Recipes and Recollections of Italian Holidays Helen Barolini Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2002

- ^ The Lure of Volcanoes James Hamilton History Today Volume 60 Issue 7 July 2010

External links

- European Volcanological Society

- United States Geological Survey- Volcanic Hazards Program

- Volcano Live – What is a volcanologist?

- Vulcanology on In Our Time at the BBC

- World Organization of Volcano Observatories

- Strother, French (April 1915). "Frank A. Perret, Volcanologist". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXX: 85–98. Retrieved 2009-08-04.