Walters Art Museum

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

BaltimoreLink routes Green, Pink, Silver, 51, 95, 103, 410, 411 Charm City Circulator Purple Route | |

| Website | thewalters |

|---|---|

Walters Art Museum is a public art museum located in the Mount Vernon section of Baltimore, Maryland. Founded and opened in 1934, it holds collections from the mid-19th century that were amassed substantially by major American art and sculpture collectors, including William Thompson Walters and his son Henry Walters. William Walters began collecting when he moved to Paris as a nominal Confederate loyalist at the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, and Henry Walters refined the collection and made arrangements for the construction what ultimately was Walters Art Museum.

After allowing the Baltimore public to occasionally view his father's and his growing added collections at his West Mount Vernon Place mansion during the late 1800s, Henry Walters arranged for an elaborate stone

The mansion and gallery were also just south and west of the landmark

In 2000, "The Walters Art Gallery" changed its long-time name to "The Walters Art Museum"[1] to reflect its image as a large public institution and eliminate confusion among some of the increasing out-of-state visitors. The following year, "The Walters" (as it is often known locally) reopened its original main building after a dramatic three-year physical renovation and replacement of internal utilities and infrastructure. The Archimedes Palimpsest was on loan to the Walters Art Museum from a private collector for conservation and spectral imaging studies.

Starting on October 1, 2006, the museum was enabled to make admission free to all, year-round, as a result of substantial grants given by Baltimore City and the surrounding suburban

Permanent collection

Ancient art

The Walters' collection of ancient art includes examples from Egypt, Nubia, Greece, Rome, Etruria and the Near East. Highlights include two monumental 3,000-pound statues of the Egyptian lion-headed fire goddess Sekhmet on long-term loan from the British Museum; the Walters Mummy; alabaster reliefs from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II; Greek gold jewelry, including the Greek bracelets from Olbia on the shores of the Black Sea; the Praxitelean Satyr; a large assemblage of Roman portrait heads; a Roman bronze banquet couch, and marble sarcophagi from the tombs of the prominent Licinian and Calpurnian families.

-

Sumerianmale worshiper, c. 2300 BC

Art of the ancient Americas

In 1911, Henry Walters purchased almost 100 gold artifacts from the

-

Whistle in the form of a dancing figure from Colima, Mexico, pottery, c. 300 B.C. - A.D. 200

-

Maya head in stucco, A.D. 550-850

-

Mixteca-Puebla style labret, obsidian

-

11th century doll

Asian art

Highlights of the

The museum holds one of the largest and finest collections of

-

Head of aJain Tirthankara, India, 10th century

-

'Mandala of Padmavati' - bronze statue of Goddess Padmavati, India, 11th century

-

Brass idol of tirthankar Parshvanatha, India, 16th century

-

Detail of Ming dynasty wood and lacquer Guanyin

-

15th-century Tibet, a ritual knife and chopper

-

19th-centuryVessantara Jataka, Ch 10

-

18th-century Chinese jar with dragon

-

woodblock print, Japan, 1920

Islamic art

-

EarlyQur'an page in Kufic script, 9th century

-

The Death of Darius,MS W.613

-

Detail of an 18th-century ceremonial jeweled Turkish rifle

-

Inside ofQur'an cover, 19th century, sub-Saharan Africa

Medieval European art

Henry Walters assembled a collection of art produced during the Middle Ages in all the major artistic media of the period. This forms the basis of the Walters'

The Walters' medieval collection features unique objects such as the Byzantine agate Rubens Vase that belonged to the painter

Many of these works are on display in the museum's galleries. Works from the medieval collection are also frequently included in special touring exhibitions, such as Treasures of Heaven, an exhibition about

Works in the medieval collection are the subject of active research by the curatorial and conservation departments of the museum, and visiting researchers frequently make use of the museum's holdings. In-depth technical research carried on these objects is made available to the public through publications and exhibitions, as in the case of the Amandus Shrine (accession no. 53.9), which was featured in a small special exhibition titled The Special Dead in 2008–09.

-

horse trappings, 4th century

-

French Gothic ivory Box Lid with a Tournament, 14th century (Walters 71274)

-

Leaf from BarbavaraBook of Hours, Milanc. 1440

-

15th centuryResurrection of Christ

-

German chandelier, red deer antler and wood, 15th century

There are also Late Medieval devotional Italian paintings by these painters at the Walters:

Renaissance, Baroque and 18th-century European art

The collection of European Renaissance and Baroque art features holdings of paintings, sculpture, furniture, ceramics, metal work, arms and armor. The highlights include

-

The Ideal City (c. 1480–1484) attributed to Fra Carnevale

-

Leaf from Book of Hours, French Renaissance, 1524

-

Therock crystal for a Medici Cardinal by Giovanni Bernardi, 1530s

-

The Sacrifice of Polyxena, Giambattista Pittoni

-

Cardinal Prospero Colonna di Sciarra, c. 1750

19th-century European art

William and Henry Walters collected works by late-19th-century French academic masters and

Henry Walters was particularly interested in the courtly arts of 18th-century France. The museum's collection of

The Walters' collection presents an overview of 19th-century European art, particularly art from

-

Raby Castle, the Seat of the Earl of Darlington (1817) byJoseph Mallord William Turner

-

The Catskills (1859) by Asher Brown Durand.

-

News from Afar (1860) by Alfred Stevens, (Exhibition: "Salute to Belgium, 1980)

-

Springtime (1872) by Claude Monet.

-

The Café-Concert (ca. 1879) by Édouard Manet.

-

Léon Bonvin - Still Life on Kitchen Table with Celery, Parsley, Bowl, and Cruets - Walters 371504

Drawings

-

Confessional, Toledo, by Félicien Rops, 1889

-

Courtier Standing by a Column, by Adolphe-René Lefèvre, c. 1860

-

Street Scene with Gothic Building, by Théodore Henri Mansson, 1845

Buildings

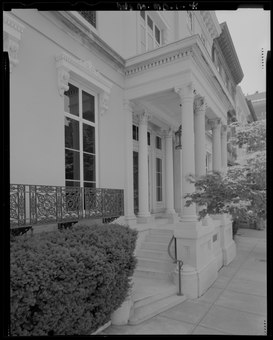

Charles Street – Old Main Building (1905–1909)

Henry Walters' original gallery was designed by architect

Centre Street Annex Building (1974)

Designed by the

Hackerman House (1850/1991)

This

Among the original owning family of the Thomas's distinguished guests of the mid-19th century were the

Anti-Labor Hostility

Throughout 2021, director

Gallery

This is a list of selected works from the museum collection.

-

The Sailor's Wedding (1852) by Richard Caton Woodville

-

9th-century Irishring brooch

-

Ethiopian miniature ofGunda Gunde Gospel Book, c. 1540

-

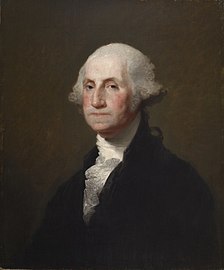

George Washington (1825) by Gilbert Stuart

-

The Church at Eragny (1884) by Camille Pissarro

-

Margot in Blue (1902) by Mary Cassatt.

-

Pendant with a Lion, Flemish, (between 1600 and 1650) Baroque

-

Iris Corsage Ornament (c. 1900) byTiffany & Company.

See also

- Collaboration Between Walters Art Museum and Wikimedia Commons

- Union busting

- American Art Collaborative

- Archimedes Palimpsest

- Baltimore Museum of Art

- William Henry Rinehart

- Peabody Institute

- George Peabody Library

- Charles Street

- Washington Monument

- Parker Building (New York City), earlier location of Walters' art collection

References

- ^ a b c "From Gallery to Museum". Walters Art Museum. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Free Admission at Baltimore Museum of Art and Walters Art museum begins October 1" (Press release). Walters Art Museum. May 31, 2006. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ a b McCauley, Mary Carole (May 8, 2012). "Walters donates artwork images to Wikipedia". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ Guide to the Collections, p. 14–15

- ^ "The Walters Art Museum". KWM Architecture. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Guide to the Collections, p. 18

- City of Baltimore. p. 22. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ "Union Avoidance". Our Services. Shawe Rosenthal LLP.

- ^ Kirkman, Rebekah. "The Way Forward for Walters Workers United". BmoreArt. BmoreArt. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Emily. "Walters Museum workers appeal to City Council members in union efforts". WYPR. WYPR. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Marciari-Alexander, Julia. "Remarks to the Education, Workforce, and Youth Committee of the Baltimore City Council" (PDF). The Walters Art Museum. The Walters Art Museum. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Kirkman, Rebekah (June 2, 2022). "Pratt Library Workers Intend to Form a Union". bmoreart. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- The Walters Art Museum.

Additional sources

- The Walters Art Gallery, Guide to the Collections, 1997, Scala Books, ISBN 978-0911886481

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Gruelle, R. B., Collection of William Thompson Walters (Boston 1895)

- Bushnell, S. W., Oriental Ceramic Art Collections of William Thompson Walters (New York 1899)

External links

- Official website

- Walters Art Museum online collection

- Archimedes Palimpsest Project Web Page

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. MD-1209, "Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Independent City, MD"

- Walters Art Museum within Google Arts & Culture

Media related to Walters Art Museum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Walters Art Museum at Wikimedia Commons

![Moveable ring from 664 to 322 BC. Green jasper and gold.[13] The Walters Art Museum.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Egyptian_-_Finger_Ring_with_a_Representation_of_Ptah_-_Walters_42387_-_Side_A.jpg/229px-Egyptian_-_Finger_Ring_with_a_Representation_of_Ptah_-_Walters_42387_-_Side_A.jpg)