Wars of Castro

| The Wars of Castro | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

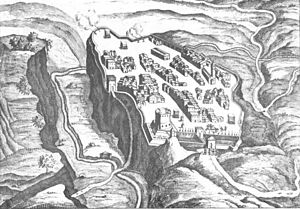

The city of Castro, on which the Wars of Castro centered. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Papal armies of Pope Urban VIII and later of Pope Innocent X |

Ranuccio II Farnese | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Mattias de' Medici as commander of the forces of the Republic of Venice, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Duchy of Modena and Reggio Francesco I d'Este | |||||||

The Wars of Castro were a series of conflicts during the mid-17th century revolving around the ancient city of

Precursors

Papal politics of the mid-17th century were complicated, with frequently shifting military and political alliances across the

In 1611 a group of

However, tensions between the Farnese and other Italian nobility were not limited to local events in Parma. Historian

The nephews were furious and convinced the pope to punish the Duke by banning grain shipments originating in Castro from being distributed in Rome and the surrounding territory, thereby depriving the Duke of an important source of income.[3] Duke Odoardo's Roman creditors saw their chance - the Duke was unable to pay his debts, which he had accumulated in military adventures against the Spanish in Milan and in luxurious living. The unpaid and unhappy creditors sought relief from the pope, who turned to military action in an attempt to force payment.[2]

Preparations for war

Pope Urban VIII responded to the requests of Duke Odoardo's creditors by sending his nephew Antonio, Fabrizio Savelli and Marquis Luigi Mattei to occupy the city of Castro. Papal forces also included commanders Achille d'Étampes de Valençay and Marquis Cornelio Malvasia.

At the same time, the pope sent

Urban VIII had been amassing troops in Rome throughout 1641. Mercenaries and regular troops filled the streets and Antonio Barberini was forced to institute special measures to maintain authority over the city. But the papacy needed yet more troops. The Duke of Ceri, who had been imprisoned for wounding a papal officer in a dispute over the management of the Duchy of Ceri, and Mario Frangipani, imprisoned for murdering someone on his estate, were both pardoned by the pope and given command of papal troops.[5]

First War of Castro

On 12 October, Luigi Mattei led 12,000

On 13 January, Urban

At first, Pope Urban threatened to excommunicate anyone who helped Odoardo, but Odoardo's allies insisted their conflict was not with the papacy, but rather with the Barberini family (of which the Pope happened to be a member). When this failed, the Pope attempted to call on old alliances of his own and turned to Spain for assistance. But he received little help as Spanish forces were fully occupied by the

Exasperated, the Pope increased taxes and raised additional forces and the war continued with Cardinal Antonio Barberini (Taddeo's brother) finding success against the Venetians and Modenese. But Papal forces suffered significant defeats in the area around Lake Trasimeno at the hands of the Tuscans (the Battle of Mongiovino). Fighting in the style typical of 17th-century Europe, by the latter half of 1643 neither side had made significant ground, though both sides had spent significant amounts of money perpetuating the conflict. It has been suggested that Pope Urban and forces loyal to the Barberini spent some 6 million thalers[7] during the 4 years of the conflict that fell within Pope Urban's reign.

The papal forces suffered a crucial defeat at the Battle of Lagoscuro on 17 March 1644 and were forced to surrender. Antonio Barberini was almost captured; saved, "only by the fleetness of his horse".[2] Peace was agreed to in Ferrara on 31 March.

Under the terms of the peace, Odoardo was readmitted to the Catholic Church and his

Urban's death and Barberini exile

Pope Urban VIII died just a few months after the peace settlement was agreed to, on 29 July and on 15 September

Taddeo Barberini died in Paris in 1647 but in 1653 Antonio and Francesco Barberini were allowed to return to Rome after sealing a reconciliation with Innocent X through the marriage of Taddeo's son

Second War of Castro

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

With peace agreed to and with Barberini power-brokers dead or exiled, the citizens of Castro were left alone. But Odoardo Farnese, who had signed the original peace accord, died in 1646 and was succeeded by his son

In 1649, Ranuccio refused to pay Roman creditors as his father had agreed in the treaty signed five years prior. He also refused to recognize the new bishop of Castro, Monsignor Cristoforo Giarda, appointed by Pope Innocent X. When the bishop was killed en route to Castro, near Monterosi, Pope Innocent X accused Duke Ranuccio and his supporters of murdering him.

In retaliation for this alleged crime, forces loyal to the Pope marched on Castro. Ranuccio attempted to ride out against the Pope's forces but was routed by Luigi Mattei.[9] On 2 September, on the Pope's orders, the city was completely destroyed. Not only did Pope Innocent's troops destroy the fortifications and general buildings of Castro, they destroyed the churches as well so as to completely sever all links between the city and the papacy.[10] As a final insult, the troops destroyed Duke Ranuccio's family Palazzo Farnese and erected a column reading Qui fu Castro ("Here stood Castro").

Duke Ranuccio II was forced to cede control of the territories around Castro to the pope, who then attempted to use the land to settle debts with Ranuccio's creditors. This marked the end of the Second War of Castro and the end of Castro itself – the city was never rebuilt.

References

- ^ Farnese: Pomp, Power and Politics in Renaissance Italy by Helge Gamrath (2007)

- ^ a b c d e f g History of the popes; their church and state (Volume III) by Leopold von Ranke (Wellesley College Library, 2009)

- ^ War over Parma by Alexander Ganse (KLMA, 2004)

- ^ Pope Alexander the Seventh and the College of Cardinals by John Bargrave, edited by James Craigie Robertson (reprint; 2009)

- ^ Power And Religion in Baroque Rome: Barberini Cultural Policies by P. J. A. N. Rietbergen (Brill, 2006)

- ^ The Castro Wars Archived 3 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine by Paul Armas Lepisto (Olive University)

- ^ "The Thirty Years' War" by Geoffrey Parker (Routledge, 1997)

- ^ The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church by S. Miranda (Florida International University, 2003)

- ^ "Cours d'histoire des états européens depuis le bouleversement de l'Empire" by Maximilian Samson Friedrich Schoell. Books.google.com.au. Retrieved on 2 September 2011.

- ^ Venice, Austria and the Turks in the seventeenth century by Kenneth Meyer Setton (American Philosophical Society, 1991)

Villari, Luigi (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 183–184.