Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C. | |

|---|---|

National Cathedral, Washington Metro, stores in Adams Morgan, National Air and Space Museum, White House . | |

|

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): D.C., The District | |

| Motto(s): Justitia Omnibus (English: Justice for All) | |

| Anthem: "Washington" "Our Nation's Capital" (march)[1] | |

Interactive map of Washington, D.C. | |

Neighborhoods of Washington, D.C. | |

| Coordinates: 38°54′17″N 77°00′59″W / 38.90472°N 77.01639°W | |

| Country | United States |

| Residence Act | July 16, 1790 |

| Organized | February 27, 1801 |

| Consolidated | February 21, 1871 |

| Home Rule Act | December 24, 1973 |

| Named for | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Muriel Bowser (D) |

| • D.C. Council |

|

| • UTC−4 (EDT) | |

| ZIP Codes | 20001–20098, 20201–20599, 56901–56999 |

| Area code(s) | 202 and 771[11][12] |

| ISO 3166 code | US-DC |

| Airports |

|

| Railroads | |

| Website | dc |

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly called Washington or D.C., is the

Washington, D.C., anchors the southern end of the Northeast megalopolis, one of the nation's largest and most influential cultural, political, and economic regions. As the seat of the U.S. federal government and several international organizations, the city is an important world political capital.[16] The city had 20.7 million domestic visitors[17] and 1.2 million international visitors, ranking seventh among U.S. cities as of 2022.[18]

The U.S. Constitution in 1789 called for the creation of a federal district under the exclusive jurisdiction of the U.S. Congress. As such, Washington, D.C., is not part of any state, and is not one itself. The Residence Act, adopted on July 16, 1790, approved the creation of the capital district along the Potomac River. The city was founded in 1791, and the 6th Congress held the first session in the unfinished Capitol Building in 1800 after the capital moved from Philadelphia. In 1801, the District of Columbia, formerly part of Maryland and Virginia and including the existing settlements of Georgetown and Alexandria, was officially recognized as the federal district; initially, the city was a separate settlement within the larger district.[19] In 1846, Congress returned the land originally ceded by Virginia, including the city of Alexandria. In 1871, it created a single municipality for the remaining portion of the district, although its locally elected government only lasted three years and elective city-government did not return for over a century.[20] There have been several unsuccessful efforts to make the district into a state since the 1880s; a statehood bill passed the House of Representatives in 2021 but was not adopted by the U.S. Senate.[21]

Designed in 1791 by Pierre Charles L'Enfant, the city is divided into quadrants, which are centered around the Capitol Building and include 131 neighborhoods. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 689,545,[3] making it the 23rd-most populous city in the U.S., third-most populous city in the Southeast after Jacksonville and Charlotte, and third-most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic after New York City and Philadelphia.[22] Commuters from the city's Maryland and Virginia suburbs raise the city's daytime population to more than one million during the workweek.[23] The Washington metropolitan area, which includes parts of Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia, is the country's seventh-largest metropolitan area, with a 2023 population of 6.3 million residents.[6]

The city hosts the U.S. federal government and the buildings that house government headquarters, including the White House, the Capitol, the Supreme Court Building, and multiple federal departments and agencies. The city is home to many national monuments and museums, located most prominently on or around the National Mall, including the Jefferson Memorial, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Washington Monument. It hosts 177 foreign embassies and serves as the headquarters for the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Organization of American States, and other international organizations. Many of the nation's largest industry associations, non-profit organizations, and think tanks are based in the city, including AARP, American Red Cross, Atlantic Council, Brookings Institution, National Geographic Society, The Heritage Foundation, Wilson Center, and others.

History

Various tribes of the Algonquian-speaking Piscataway people, also known as the Conoy, inhabited the lands around the Potomac River and present-day Washington, D.C., when Europeans first arrived and colonized the region in the early 17th century. The Nacotchtank, also called the Nacostines by Catholic missionaries, maintained settlements around the Anacostia River in present-day Washington, D.C. Conflicts with European colonists and neighboring tribes ultimately displaced the Piscataway people, some of whom established a new settlement in 1699 near Point of Rocks, Maryland.[24]

Founding

Several other cities served as the U.S. capital before 1800. Philadelphia served as the capital on five separate occasions during the American Revolution and its aftermath from May 1775 to July 1776, December 1776 to February 1777, March 1777 to September 1777, July 1778, July 1778 to March 1781, and March 1781 to June 1783. The Continental Congress was briefly based in five additional locations: York, Pennsylvania, in September 1777; Princeton, New Jersey, in 1783; Annapolis, Maryland, from November 1783 to August 1784; Trenton, New Jersey, from November to December 1784; and New York City from January 1785 to March 1789.

On October 6, 1783, after the capital was forced by the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 to move to Princeton, Congress resolved to consider a new location for it.[25] The following day, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts moved "that buildings for the use of Congress be erected on the banks of the Delaware near Trenton, or of the Potomac, near Georgetown, provided a suitable district can be procured on one of the rivers as aforesaid, for a federal town".[26]

In Federalist No. 43, published January 23, 1788, James Madison argued that the new federal government would need authority over a national capital to provide for its own maintenance and safety.[27] The Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 emphasized the need for the national government not to rely on any state for its own security.[28]

Article One, Section Eight of the U.S. Constitution permits the establishment of a "District (not exceeding ten miles square) as may, by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of the government of the United States".[29] However, the constitution does not specify a location for the capital. In the Compromise of 1790, Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson agreed that the federal government would pay each state's remaining Revolutionary War debts in exchange for establishing the new national capital in the Southern United States.[30][a]

On July 9, 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which approved the creation of a national capital on the Potomac River. Under the Residence Act, the exact location was to be selected by President George Washington, who signed the bill into law on July 16, 1790. Formed from land donated by Maryland and Virginia, the initial shape of the federal district was a square measuring 10 miles (16 km) on each side and totaling 100 square miles (259 km2).[31][b]

Two pre-existing settlements were included in the territory, the port of

After its survey, the new federal city was constructed on the north bank of the Potomac River, to the east of Georgetown centered on Capitol Hill. On September 9, 1791, three commissioners overseeing the capital's construction named the city in honor of President Washington. The same day, the federal district was named Columbia, a feminine form of Columbus, which was a poetic name for the United States commonly used at that time.[38][39] Congress held its first session there on November 17, 1800.[40][41]

Congress passed the

Burning during War of 1812

On August 24, 1814, during the War of 1812, British forces invaded and occupied the city after defeating an American force at Bladensburg. In retaliation for acts of destruction by American troops in the Canadas, the British set fire to government buildings in the city, gutting the United States Capitol, the Treasury Building, and the White House in what became known as the burning of Washington. However, a storm forced the British to evacuate the city after just 24 hours.[44] Most government buildings were repaired quickly, but the Capitol, which was largely under construction at the time, would not be completed in its current form until 1868.[45]

Retrocession and the Civil War

In the 1830s, the district's southern territory of Alexandria declined economically, due in part to its neglect by Congress.[46] Alexandria was a major market in the domestic slave trade and pro-slavery residents feared that abolitionists in Congress would end slavery in the district, further depressing the local economy. Alexandria's citizens petitioned Virginia to retake the land it had donated to form the district, a process known as retrocession.[47]

The Virginia General Assembly voted in February 1846, to accept the return of Alexandria. On July 9, 1846, Congress went further, agreeing to return all territory that Virginia had ceded to the district during its formation. This left the district's area consisting only of the portion originally donated by Maryland.[46] Confirming the fears of pro-slavery Alexandrians, the Compromise of 1850 outlawed the slave trade in the district, although not slavery itself.[48]

The outbreak of the

Growth and redevelopment

By 1870, the district's population had grown 75% in a decade to nearly 132,000 people,[51] yet the city still lacked paved roads and basic sanitation. Some members of Congress suggested moving the capital farther west, but President Ulysses S. Grant refused to consider the proposal.[52]

In the Organic Act of 1871, Congress repealed the individual charters of the cities of Washington and Georgetown, abolished Washington County, and created a new territorial government for the whole District of Columbia.[53] These steps made "the city of Washington...legally indistinguishable from the District of Columbia."[19]

In 1873, President Grant appointed Alexander Robey Shepherd as Governor of the District of Columbia. Shepherd authorized large projects that modernized the city but bankrupted its government. In 1874, Congress replaced the territorial government with an appointed three-member board of commissioners.[54]

In 1888, the city's first motorized streetcars began service. Their introduction generated growth in areas of the district beyond the City of Washington's original boundaries, leading to an expansion of the district over the next few decades.[55] Georgetown's street grid and other administrative details were formally merged with those of the City of Washington in 1895.[56] However, the city had poor housing and strained public works, leading it to become the first city in the nation to undergo urban renewal projects as part of the City Beautiful movement in the early 20th century.[57]

The City Beautiful movement built heavily upon the already-implemented L'Enfant Plan, with the new McMillan Plan leading urban development in the city throughout the movement. Much of the old Victorian Mall was replaced with modern Neoclassical and Beaux-Arts architecture; these designs are still prevalent in the city's governmental buildings today.

Increased federal spending under the New Deal in the 1930s led to the construction of new government buildings, memorials, and museums in the district,[58] though the chairman of the House Subcommittee on District Appropriations, Ross A. Collins of Mississippi, justified cuts to funds for welfare and education for local residents by saying that "my constituents wouldn't stand for spending money on niggers."[59]

World War II led to an expansion of federal employees in the city;[60] by 1950, the district's population reached its peak of 802,178 residents.[51]

Civil rights and home rule era

The

After the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, riots broke out in the city, primarily in the U Street, 14th Street, 7th Street, and H Street corridors, which were predominantly black residential and commercial areas. The riots raged for three days until more than 13,600 federal troops and Washington, D.C., Army National Guardsmen stopped the violence. Many stores and other buildings were burned, and rebuilding from the riots was not completed until the late 1990s.[62]

In 1973, Congress enacted the District of Columbia Home Rule Act providing for an elected mayor and 13-member council for the district.[63] In 1975, Walter Washington became the district's first elected and first black mayor.[64]

Since the 1980s, the D.C. statehood movement has grown in prominence. In 2016, a referendum on D.C. statehood resulted in an 85% support among Washington, D.C., voters for it to become the nation's 51st state. In March 2017, the city's congressional delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton introduced a bill for statehood. Reintroduced in 2019 and 2021 as the Washington, D.C., Admission Act, the U.S. House of Representatives passed it in April 2021. After not progressing in the Senate, the statehood bill was introduced again in January 2023.[65]

Geography

Washington, D.C., is located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. East Coast. The city has a total area of 68.34 square miles (177 km2), of which 61.05 square miles (158.1 km2) is land and 7.29 square miles (18.9 km2) (10.67%) is water.[66] The district is bordered by Montgomery County, Maryland, to the northwest; Prince George's County, Maryland, to the east; Arlington County, Virginia, to the west; and Alexandria, Virginia, to the south. Washington is 38 miles (61 km) from Baltimore, 124 miles (200 km) from Philadelphia, 227 miles (365 km) from New York City, 242 miles (389 km) from Pittsburgh, 384 miles (618 km) from Charlotte, and 439 miles (707 km) from Boston.[citation needed]

The south bank of the

The highest natural elevation in the district is 409 feet (125 m)

The district has 7,464 acres (30.21 km2) of parkland, about 19% of the city's total area, the second-highest among high-density U.S. cities after Philadelphia.[76] The city's sizable parkland was a factor in the city being ranked as third in the nation for park access and quality in the 2018 ParkScore ranking of the park systems of the nation's 100 most populous cities, according to Trust for Public Land, a non-profit organization.[77]

The

Climate

Washington's climate is humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa), or oceanic (Trewartha: Do bordering Cf downtown).[83][84] Winters are cool to cold with some snow of varying intensity, while summers are hot and humid. The district is in plant hardiness zone 8a near downtown, and zone 7b elsewhere in the city.[85][86]

Summers are hot and humid with a July daily average of 79.8 °F (26.6 °C) and average daily relative humidity around 66%, which can cause moderate personal discomfort. Heat indices regularly approach 100 °F (38 °C) at the height of summer.[87] The combination of heat and humidity in the summer brings very frequent thunderstorms, some of which occasionally produce tornadoes in the area.[88]

Blizzards affect Washington once every four to six years on average. The most violent storms, known as nor'easters, often impact large regions of the East Coast.[89] From January 27 to 28, 1922, the city officially received 28 inches (71 cm) of snowfall, the largest snowstorm since official measurements began in 1885.[90] According to notes kept at the time, the city received between 30 and 36 inches (76 and 91 cm) from a snowstorm in January 1772.[91]

Hurricanes or their remnants occasionally impact the area in late summer and early fall. However, they usually are weak by the time they reach Washington, partly due to the city's inland location.[92] Flooding of the Potomac River, however, caused by a combination of high tide, storm surge, and runoff, has been known to cause extensive property damage in the Georgetown neighborhood of the city.[93] Precipitation occurs throughout the year.[94]

The highest recorded temperature was 106 °F (41 °C) on August 6, 1918, and on July 20, 1930.[95] The lowest recorded temperature was −15 °F (−26 °C) on February 11, 1899, right before the Great Blizzard of 1899.[89] During a typical year, the city averages about 37 days at or above 90 °F (32 °C) and 64 nights at or below the freezing mark (32 °F or 0 °C).[96] On average, the first day with a minimum at or below freezing is November 18 and the last day is March 27.[97][98]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

84 (29) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

98 (37) |

86 (30) |

79 (26) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 66.7 (19.3) |

68.1 (20.1) |

77.3 (25.2) |

86.4 (30.2) |

91.0 (32.8) |

95.7 (35.4) |

98.1 (36.7) |

96.5 (35.8) |

91.9 (33.3) |

84.5 (29.2) |

74.8 (23.8) |

67.1 (19.5) |

99.1 (37.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 44.8 (7.1) |

48.3 (9.1) |

56.5 (13.6) |

68.0 (20.0) |

76.5 (24.7) |

85.1 (29.5) |

89.6 (32.0) |

87.8 (31.0) |

80.7 (27.1) |

69.4 (20.8) |

58.2 (14.6) |

48.8 (9.3) |

67.8 (19.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37.5 (3.1) |

40.0 (4.4) |

47.6 (8.7) |

58.2 (14.6) |

67.2 (19.6) |

76.3 (24.6) |

81.0 (27.2) |

79.4 (26.3) |

72.4 (22.4) |

60.8 (16.0) |

49.9 (9.9) |

41.7 (5.4) |

59.3 (15.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 30.1 (−1.1) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

38.6 (3.7) |

48.4 (9.1) |

58.0 (14.4) |

67.5 (19.7) |

72.4 (22.4) |

71.0 (21.7) |

64.1 (17.8) |

52.2 (11.2) |

41.6 (5.3) |

34.5 (1.4) |

50.9 (10.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 14.3 (−9.8) |

16.9 (−8.4) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

34.9 (1.6) |

45.5 (7.5) |

55.7 (13.2) |

63.8 (17.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

51.3 (10.7) |

38.7 (3.7) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

12.3 (−10.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−15 (−26) |

4 (−16) |

15 (−9) |

33 (1) |

43 (6) |

52 (11) |

49 (9) |

36 (2) |

26 (−3) |

11 (−12) |

−13 (−25) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.86 (73) |

2.62 (67) |

3.50 (89) |

3.21 (82) |

3.94 (100) |

4.20 (107) |

4.33 (110) |

3.25 (83) |

3.93 (100) |

3.66 (93) |

2.91 (74) |

3.41 (87) |

41.82 (1,062) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.9 (12) |

5.0 (13) |

2.0 (5.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.7 (4.3) |

13.7 (35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.7 | 9.3 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 10.6 | 10.5 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 10.1 | 117.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.8 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 8.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%)

|

62.1 | 60.5 | 58.6 | 58.0 | 64.5 | 65.8 | 66.9 | 69.3 | 69.7 | 67.4 | 64.7 | 64.1 | 64.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 21.7 (−5.7) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

52.3 (11.3) |

61.5 (16.4) |

66.0 (18.9) |

65.8 (18.8) |

59.5 (15.3) |

47.5 (8.6) |

37.0 (2.8) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

44.4 (6.9) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 144.6 | 151.8 | 204.0 | 228.2 | 260.5 | 283.2 | 280.5 | 263.1 | 225.0 | 203.6 | 150.2 | 133.0 | 2,527.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 48 | 50 | 55 | 57 | 59 | 64 | 62 | 62 | 60 | 59 | 50 | 45 | 57 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Source 1: | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[102] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Cityscape

Washington, D.C., was a

By the early 20th century, however, L'Enfant's vision of a grand national capital was marred by slums and randomly placed buildings in the city, including a railroad station on the National Mall. Congress formed a special committee charged with beautifying Washington's ceremonial core.[57] What became known as the McMillan Plan was finalized in 1901 and included relandscaping the Capitol grounds and the National Mall, clearing slums, and establishing a new citywide park system. The plan is thought to have largely preserved L'Enfant's intended design for the city.[104]

By law, the city's skyline is low and sprawling. The federal Height of Buildings Act of 1910 prohibits buildings exceeding the width of the adjacent street plus 20 feet (6.1 m).[108] Despite popular belief, no law has ever limited buildings to the height of the United States Capitol or the 555-foot (169 m) Washington Monument,[75] which remains the district's tallest structure. City leaders have cited the height restriction as a primary reason that the district has limited affordable housing and its metro area has suburban sprawl and traffic problems.[108] Washington, D.C., still has a relatively high homelessness rate, despite its high living standard compared to many American cities.[citation needed]

Washington, D.C., is divided into

- Selection of neighborhoods in Washington, D.C.

-

Chinatown

The City of Washington was bordered on the north by Boundary Street (renamed

Architecture

The architecture of Washington, D.C., varies greatly and is generally popular among tourists and locals. In 2007, six of the top ten buildings in the American Institute of Architects' ranking of America's Favorite Architecture were in the city:[113] the White House, Washington National Cathedral, the Jefferson Memorial, the United States Capitol, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. The neoclassical, Georgian, Gothic, and Modern styles are reflected among these six structures and many other prominent edifices in the city.[citation needed]

Many of the government buildings, monuments, and museums along the

Notable contemporary residential buildings, restaurants, shops, and office buildings in the city include the Wharf on the Southwest Waterfront, Navy Yard along the Anacostia River, and CityCenterDC in Downtown. The Wharf has seen the construction of several high-rise office and residential buildings overlooking the Potomac River. Additionally, restaurants, bars, and shops have been opened at street level. Many of these buildings have a modern glass exterior and heavy curvature.[122][123] CityCenterDC is home to Palmer Alley, a pedestrian-only walkway, and houses several apartment buildings, restaurants, and luxury-brand storefronts with streamlined glass and metal facades.[124]

Outside Downtown D.C., architectural styles are more varied. Historic buildings are designed primarily in the

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 8,144 | — | |

| 1810 | 15,471 | 90.0% | |

| 1820 | 23,336 | 50.8% | |

| 1830 | 30,261 | 29.7% | |

| 1840 | 33,745 | 11.5% | |

| 1850 | 51,687 | 53.2% | |

| 1860 | 75,080 | 45.3% | |

| 1870 | 131,700 | 75.4% | |

| 1880 | 177,624 | 34.9% | |

| 1890 | 230,392 | 29.7% | |

| 1900 | 278,718 | 21.0% | |

| 1910 | 331,069 | 18.8% | |

| 1920 | 437,571 | 32.2% | |

| 1930 | 486,869 | 11.3% | |

| 1940 | 663,091 | 36.2% | |

| 1950 | 802,178 | 21.0% | |

| 1960 | 763,956 | −4.8% | |

| 1970 | 756,510 | −1.0% | |

| 1980 | 638,333 | −15.6% | |

| 1990 | 606,900 | −4.9% | |

| 2000 | 572,059 | −5.7% | |

| 2010 | 601,723 | 5.2% | |

| 2020 | 689,545 | 14.6% | |

| Source:[130] [e][51][131] Note:[f] 2010–2020[3] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2020[133] | 2010[134] | 1990[135] | 1970[135] | 1940[135] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

White

|

39.6% | 38.5% | 29.6% | 27.7% | 71.5% |

| —Non-Hispanic whites | 38.0% | 34.8% | 27.4% | 26.5%[g] | 71.4% |

Black or African American

|

41.4% | 50.7% | 65.8% | 71.1% | 28.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 11.3% | 9.1% | 5.4% | 2.1%[g] | 0.1% |

Asian

|

4.8% | 3.5% | 1.8% | 0.6% | 0.2% |

The

The

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 4,410 homeless people in Washington, D.C.[143][144]

According to 2017 Census Bureau data, the population of Washington, D.C., was 47.1% Black or African American, 45.1% White (36.8% non-Hispanic White), 4.3%

Washington, D.C. has had a relatively large

About 17% of Washington, D.C. residents were age 18 or younger as of 2010, lower than the U.S. average of 24%. However, at 34 years old, the district had the lowest median age compared to the 50 states as of 2010.

As of 2010, there were 4,822 same-sex couples in the city, about 2% of total households, according to Williams Institute.[151] Legislation authorizing same-sex marriage passed in 2009, and the district began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples in March 2010.[152]

As of 2007, about one-third of Washington, D.C., residents were

As of 2010[update], more than 90% of Washington, D.C., residents had health insurance coverage, the second-highest rate in the nation. This is due in part to city programs that help provide insurance to low-income individuals who do not qualify for other types of coverage.[160] A 2009 report found that at least three percent of Washington, D.C., residents have HIV or AIDS, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) characterizes as a "generalized and severe" epidemic.[161]

Of the district's population, 17% are

Economy

As of 2023, the

Between 2009 and 2016, gross domestic product per capita in Washington, D.C., consistently ranked at the very top among U.S. states.[166] In 2016, at $160,472, its GDP per capita was almost three times greater than that of Massachusetts, which was ranked second in the nation (see List of U.S. states and territories by GDP).[166] As of 2022[update], the metropolitan statistical area's unemployment rate was 3.1%, ranking 171 out of the 389 metropolitan areas as defined by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.[167] The District of Columbia itself had an unemployment rate of 4.6% during the same time period.[168] In 2019, Washington, D.C., had the highest median household income in the U.S. at $92,266.[169]

According to the District's

Federal government

As of July 2022, 25% of people employed in Washington, D.C., were employed by the federal government.

Many of the region's residents are employed by companies and organizations that do work for the federal government, seek to

Diplomacy and global finance

As the national capital, Washington, D.C. hosts about 185 foreign missions, including embassies, ambassador's residences, and international cultural centers.[173] Many are concentrated along a stretch of Massachusetts Avenue known informally as Embassy Row.[174] D.C. is consequently one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world; it hosts a number of internationally themed festivals and events, often in collaboration with foreign missions or delegations.[175][176]

In 2008, the foreign diplomatic corps employed about 10,000 people and contributed an estimated $400 million annually to the local economy.[177] The city government maintains an Office of International Affairs to liaise with the diplomatic community and foreign delegations.[178]

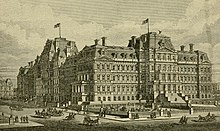

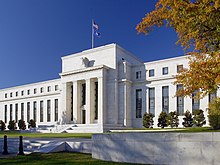

The Federal Reserve, the central bank of the United States, is located on Constitution Avenue. Commonly called The Fed, its policies are made by the members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Through monetary policy, the Board adjusts various interest rates in the U.S., which affects the U.S. economy and economies of countries across the world. Because of the power of the U.S. dollar, the actions of the Board are monitored closely by political, economic, and diplomatic leaders around the world.[citation needed]

Research and non-profit organizations

Washington, D.C., is a leading center for national and international research organizations, especially think tanks engaged in public policy.[179] As of 2020, 8% of the country's think tanks are headquartered in the city, including many of the largest and most widely cited;[180] these include the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Peterson Institute for International Economics, The Heritage Foundation, and Urban Institute.[181]

D.C. is home to many non-profit organizations that engage with issues of domestic and global importance by conducting advanced research, running programs, or public advocacy. Among these organizations are the

The city is the country's primary location for international development firms, many of which contract with the D.C.-based United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. federal government's aid agency. The American Red Cross, a humanitarian agency focused on emergency relief, is also headquartered in the city.[184]

Private sector

According to statistics compiled in 2011, four of the

Due to the building height restrictions in Washington, D.C., taller buildings are able to be built in suburban

The Washington, D.C., economy also benefits from being home to many prominent news and media organizations. Among these are The Washington Post, The Washington Times, Politico, and The Hill. Television and radio media organizations either headquartered in or near the city or with large offices in the region, include CNN, PBS, C-SPAN, CBS, NBC, Discovery, and NPR, and others. The Gannett Company, which owns USA Today and other media outlets, is headquartered in Tysons, Virginia.[190][191]

Tourism

Tourism is the city's second-largest industry, after the federal government. In 2012, some 18.9 million visitors contributed an estimated $4.8 billion to the local economy.[192] In 2019, the city saw 24.6 million tourists, including 1.8 million from foreign countries, who collectively spent $8.15 billion during their stay.[193] Tourism helps many of the region's other industries, such as lodging, food and beverage, entertainment, shopping, and transportation;[193] it also supports the city's world-class museums and cultural centers, most notably the Smithsonian Institution.[citation needed]

The city and wider Washington region has a diverse array of attractions for tourists, such as monuments, memorials, museums, sports events, and trails. Within the city, the

Among the most visited tourist destinations is Arlington National Cemetery in nearby Arlington County, Virginia.[194] This is a military cemetery that serves as a burial ground for former military combatants. It is also the location of President John F. Kennedy's tomb, marked by an eternal flame.[195] President William Howard Taft is also buried in Arlington.[196] The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is located in the cemetery and is guarded 24/7 by a tomb guard. The changing of the guard is a popular tourist attraction and occurs once every hour from October through March and every half-hour during the rest of the year.[197]

Culture

Potomac bluestone | |

|---|---|

| Route marker | |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2009 | |

Arts

Washington, D.C., is a national center for the arts, home to several concert halls and theaters. The

The historic Ford's Theatre, site of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, continues to function as a theatre and as a museum.[200]

The Marine Barracks near Capitol Hill houses the United States Marine Band; founded in 1798, it is the country's oldest professional musical organization.[201] American march composer and Washington-native John Philip Sousa led the Marine Band from 1880 until 1892.[202] Founded in 1925, the United States Navy Band has its headquarters at the Washington Navy Yard and performs at official events and public concerts around the city.[203]

Founded in 1950,

Other performing arts spaces in the city include the

The

The Washington D.C. Area Film Critics Association (WAFCA), a group of more than 65 film critics, holds an annual awards ceremony.[208]

Music

Columbia Records, a major music record label in the US, was founded in Washington, D.C. in 1889.[209][210]

The city grew into being one of America's most important music cities in the early

Washington has its own native music genre called go-go; a post-funk, percussion-driven flavor of rhythm and blues that was popularized in the late 1970s by D.C. band leader Chuck Brown.[211]

The district is an important center for

Cuisine

Washington, D.C., is rich in fine and casual dining; some consider it among the country's best cities for dining.

Among the most famous Washington, D.C.-born foods is the

Among the city's signature restaurants is

D.C.'s fine dining restaurants have received more Michelin stars, as of 2023, than any other U.S. city except New York City and San Francisco. Several celebrity chefs have opened restaurants in the city, including José Andrés,[229] Kwame Onwuachi,[230] Gordon Ramsay,[231][232] and previously Michel Richard.[citation needed]

Museums

Washington, D.C. is home to many of the country's most visited museums and some of the most visited museums in the world. In 2022, the National Museum of Natural History and the National Gallery of Art were the two most visited museums in the country. Overall, Washington had eight of the 28 most visited museums in the U.S. in 2022. That year, the National Museum of Natural History was the fifth-most-visited museum in the world; the National Gallery of Art was the eleventh.[233]

Smithsonian museums

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational foundation chartered by Congress in 1846 that maintains most of the nation's official museums and galleries in Washington, D.C. It is the world's largest research and museum complex.[234] The U.S. government partially funds the Smithsonian, and its collections are open to the public free of charge.[235] The Smithsonian's locations had a combined total of 30 million visits in 2013. The most visited museum is the National Museum of Natural History on the National Mall.[236] Other Smithsonian Institution museums and galleries on the Mall include the National Air and Space Museum; the National Museum of African Art; the National Museum of American History; the National Museum of the American Indian; the Sackler and Freer galleries, which focus on Asian art and culture; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; the Arts and Industries Building; the S. Dillon Ripley Center; and the Smithsonian Institution Building, which serves as the institution's headquarters.[237]

The

Other museums

The

There are several private art museums in Washington, D.C., that house major collections and exhibits open to the public, such as the

Landmarks

National Mall and Tidal Basin

The

The

South of the mall is the

Other landmarks

Numerous historic landmarks are located outside the

The

The Southwest Waterfront along the Potomac River has been redeveloped in recent years and now serves as a popular cultural center. The Wharf, as it is called, contains the city's historic Maine Avenue Fish Market. This is the oldest fish market currently in operation in the entire United States.[262] The Wharf also has many hotels, residential buildings, restaurants, shops, parks, piers, docks and marinas, and live music venues.[122][123]

Several other landmarks are located in neighboring

As a result of its central role in United States history, the District of Columbia has many sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Parks

There are many parks, gardens, squares, and circles throughout Washington. The city has 683 parks and greenspaces, comprising almost a quarter of its land area.[264] Consequently, 99% of residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park.[265] According to the nonprofit Trust for Public Land, Washington ranked first among the 100 largest U.S. cities for its public parks, based on indicators such as accessibility, the share of land reserved for parks, and the amount invested in green spaces.[265]

There are several river islands in Washington, D.C., including Theodore Roosevelt Island in the Potomac River, which hosts the Theodore Roosevelt National Memorial and a number of trails.[269] Columbia Island, also in the Potomac, is home to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove, the Navy – Merchant Marine Memorial, and a marina. Kingman Island, in the Anacostia River, is home to Langston Golf Course and a public park with trails.[270]

Other parks, gardens, and squares include

The United States National Arboretum is a dense arboretum in Northeast D.C. filled with gardens and trails. Its most notable landmark is the National Capitol Columns monument.[272]

Sports

| Team | League | Sport | Venue | Neighborhood | Capacity | Founded (moved to Washington area) | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington Commanders | NFL | American football | Commanders Field

|

Landover, Maryland | 65,000 | 1932 (1937) | 1937, 1942, 1982, 1987, 1991 |

| Washington Wizards | NBA | Men's Basketball | Capital One Arena | Chinatown

|

20,356 | 1961 (1973) | 1978 |

| Washington Nationals | MLB | Baseball | Nationals Park | Navy Yard | 41,339 | 1969 (2005) | 2019 |

| Washington Capitals | NHL | Ice hockey | Capital One Arena | Chinatown

|

18,573 | 1974 | 2018 |

| D.C. United | MLS | Men's Soccer | Audi Field | Buzzard Point | 20,000 | 1996 | 1996, 1997, 1999, 2004[j] |

| Washington Mystics | WNBA | Women's Basketball | Entertainment and Sports Arena | Congress Heights | 4,200 | 1998 | 2019 |

| Washington Spirit | NWSL | Women's Soccer | Audi Field | Buzzard Point | 20,000 | 2012 | 2021 |

Washington, D.C. is one of 13 cities in the United States with teams from the

The city's teams have won a combined 14 professional league championships over their respective histories. The Washington Commanders (named the Washington Redskins until 2020), have won two NFL Championships and three Super Bowls;[276] D.C. United has won four;[277] and the Washington Wizards, then named the Washington Bullets, Washington Capitals, Washington Mystics, Washington Nationals, and Washington Spirit have each won a single championship.[278][279]

Other professional and semi-professional teams in Washington, D.C. include

The district's four

City government

Politics

Article One, Section Eight of the United States Constitution grants the United States Congress "exclusive jurisdiction" over the city. The district did not have an elected local government until the passage of the 1973 Home Rule Act. The Act devolved certain Congressional powers to an elected mayor and the thirteen-member Council of the District of Columbia. However, Congress retains the right to review and overturn laws created by the council and intervene in local affairs.[282] Washington, D.C., is overwhelmingly Democratic, having voted for the Democratic presidential candidate solidly since it was granted electoral votes in 1964.[citation needed]

Each of the city's eight

Washington, D.C., observes all federal holidays and also celebrates Emancipation Day on April 16, which commemorates the end of slavery in the district.[50] The flag of Washington, D.C., was adopted in 1938 and is a variation on George Washington's family coat of arms.[286]

Washington, D.C., has been a member state of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) since 2015.[287]

The idiom "Inside the Beltway" is a reference used by media to describe discussions of national political issues inside of Washington, by way of geographical demarcation regarding the region within the Capital's Beltway, Interstate 495, the city's highway loop (beltway) constructed in 1964. The phrase is used as a title for a number of political columns and news items by publications like The Washington Times.[288]

Budgetary issues

The mayor and council set local taxes and a budget, which Congress must approve. The Government Accountability Office and other analysts have estimated that the city's high percentage of tax-exempt property and the Congressional prohibition of commuter taxes create a structural deficit in the district's local budget of anywhere between $470 million and over $1 billion per year. Congress typically provides additional grants for federal programs such as Medicaid and the operation of the local justice system; however, analysts claim that the payments do not fully resolve the imbalance.[289][290]

The city's local government, particularly during the mayoralty of Marion Barry, has been criticized for mismanagement and waste.[291] During his administration in 1989, Washington Monthly magazine labeled the district "the worst city government in America".[292] In 1995, at the start of Barry's fourth term, Congress created the District of Columbia Financial Control Board to oversee all municipal spending.[293] Mayor Anthony Williams won election in 1998 and oversaw a period of urban renewal and budget surpluses.[294]

The district regained control over its finances in 2001 and the oversight board's operations were suspended.[295]

The district has a federally funded "Emergency Planning and Security Fund" to cover security related to visits by foreign leaders and diplomats, presidential inaugurations, protests, and terrorism concerns. During the Trump administration, the fund has run with a deficit. Trump's January 2017 inauguration cost the city $27 million; of that, $7 million was never repaid to the fund. Trump's 2019 Independence Day event, "A Salute to America", cost six times more than Independence Day events in past years.[296]

Voting rights debate

Washington, D.C. is not a state and therefore has no federal voting representation in

A 2005 poll found that 78% of Americans did not know residents of Washington, D.C., have less representation in Congress than residents of the 50 states.[299] Efforts to raise awareness about the issue have included campaigns by grassroots organizations and featuring the city's unofficial motto, "End Taxation Without Representation", on D.C. vehicle license plates.[300] There is evidence of nationwide approval for D.C. voting rights; various polls indicate that 61 to 82% of Americans believe D.C. should have voting representation in Congress.[299][301]

Opponents to federal voting rights for Washington, D.C., propose that the Founding Fathers never intended for district residents to have a vote in Congress since the Constitution makes clear that representation must come from the states. Those opposed to making District of Columbia a state claim such a move would destroy the notion of a separate national capital and that statehood would unfairly grant Senate representation to a single city.[302]

Homelessness

The city passed a law that requires shelter to be provided to everyone in need when the temperature drops below freezing.[303] Since D.C. does not have enough shelter units available, every winter it books hotel rooms in the suburbs with an average cost around $100 for a night. According to the D.C. Department of Human Services, during the winter of 2012 the city spent $2,544,454 on putting homeless families in hotels,[304] and budgeted $3.2 million on hotel beds in 2013.[305]

Education

District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS), the sole public school district in the city,[306] operates the city's 123 public schools.[307] The number of students in DCPS steadily decreased for 39 years until 2009. In the 2010–11 school year, 46,191 students were enrolled in the public school system.[308] DCPS has one of the highest-cost, yet lowest-performing school systems in the country, in terms of both infrastructure and student achievement.[309] Mayor Adrian Fenty's administration made sweeping changes to the system by closing schools, replacing teachers, firing principals, and using private education firms to aid curriculum development.[310]

The District of Columbia Public Charter School Board monitors the 52 public charter schools in the city.[311] Due to the perceived problems with the traditional public school system, enrollment in public charter schools had by 2007 steadily increased.[312] As of 2010, D.C., charter schools had a total enrollment of about 32,000, a 9% increase from the prior year.[308] The district is also home to 92 private schools, which enrolled approximately 18,000 students in 2008.[313]

Higher education

The

The city's medical research institutions include

Libraries

Washington, D.C., has dozens of public and private libraries and library systems, including the District of Columbia Public Library system.[citation needed] Folger Shakespeare Library, a research library and museum located in the Capitol Hill neighborhood, houses the world's largest collection of material related to William Shakespeare.[317]

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the de facto national library of the United States. It is a complex of three buildings: Thomas Jefferson Building, John Adams Building and James Madison Memorial Building, all located in the Capitol Hill neighborhood. The Jefferson Building houses the library's reading room, a copy of the Gutenberg Bible, Thomas Jefferson's original library, and several museum exhibits.[citation needed]

District of Columbia Public Library

The District of Columbia Public Library operates 26 neighborhood locations including the landmark Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library.[319]

Media

Washington, D.C., is a prominent center for national and international media.

The Washington Times is a general interest daily newspaper and popular among conservatives.[323] The alternative weekly Washington City Paper, with a circulation of 47,000, is also based in the city and has a substantial readership in the Washington area.[324][325]

The Atlantic magazine, which has covered politics, international affairs, and cultural issues since 1857, is headquartered at the Watergate complex in Washington.[326]

Several community and specialty papers focus on neighborhood and cultural issues, including the weekly

The

The city is served by two local NPR affiliates, WAMU and WETA.[333]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Streets and highways

There are 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of streets, parkways, and avenues in the district.

According to a 2010 study, Washington-area commuters spent 70 hours a year in traffic delays, which tied with Chicago for having the nation's worst road congestion.[337] However, 37% of Washington-area commuters take public transportation to work, the second-highest rate in the country.[338] An additional 12% of D.C. commuters walked to work, 6% carpooled, and 3% traveled by bicycle in 2010.[339]

Cycling

In May 2022, the city celebrated the expansion of its

D.C. is part of the regional

Walkability

A 2021 study by

River crossings

There are multiple transportation methods to cross the city's two rivers, the

There are also ferries and water cruises that cross the Potomac River. One of these is the Potomac Water Taxi, operated by

Rail

The

Maryland's

Although Washington, D.C. was known throughout the 19th and early- to mid-20th centuries for its streetcars, these lines were dismantled in the 1960s. In 2016, however, the city brought back a streetcar line, DC Streetcar, which is a single line system in Northeast Washington, D.C., along H Street and Benning Road, known as the H Street/Benning Road Line.[353]

Bus

Two main public bus systems operate in Washington, D.C.

Many other public bus systems operate in the various jurisdictions of the Washington region outside of the city in suburban Maryland and Virginia. Among these are the Fairfax Connector in Fairfax County, Virginia; DASH in Alexandria, Virginia; and TheBus in Prince George's County, Maryland.[357] There are also numerous commuter buses that residents of the wider Washington region take to commute into the city for work or other events. Among these are the Loudoun County Transit Commuter Bus and the Maryland Transit Administration Commuter Bus.[358]

The city also has several bus lines used by tourists and others visiting the city, including Big Bus Tours, Old Town Trolley Tours, and DC Trails. The city also has many charter buses used in carrying young students and other tourists from across the country to the city and region's historic sites. These buses are often found parked beside the city's most notable tourist attractions, including the National Mall.[citation needed]

Air

Three major airports serve the district, though none are within the city's borders. Two of these major airports are located in suburban

The President of the United States does not use any of these airports for travel. Instead, he typically travels by Marine One from the White House South Lawn to Joint Base Andrews, located in suburban Maryland. From there, he takes Air Force One to his destination. Joint Base Andrews was built in 1942. From 1942 to 2009, it was solely an Air Force base, but became a joint Air Force and Naval base in 2009, when Andrews Air Force Base and Naval Air Facility Washington were merged into a singular entity with the creation of Joint Base Andrews.[365]

Utilities

The District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority, also known as WASA or D.C. Water, is an independent authority of the Washington, D.C., government that provides drinking water and wastewater collection in the city. WASA purchases water from the historic Washington Aqueduct, which is operated by the Army Corps of Engineers. The water, sourced from the Potomac River, is treated and stored in the city's Dalecarlia, Georgetown, and McMillan reservoirs. The aqueduct provides drinking water for a total of 1.1 million people in the district and Virginia, including Arlington, Falls Church, and a portion of Fairfax County.[367] The authority also provides sewage treatment services for an additional 1.6 million people in four surrounding Maryland and Virginia counties.[368]

Pepco is the city's electric utility and services 793,000 customers in the district and suburban Maryland.[369] An 1889 law prohibits overhead wires within much of the historic City of Washington. As a result, all power lines and telecommunication cables are located underground in downtown Washington, and traffic signals are placed at the edge of the street.[370] A 2013 plan would bury an additional 60 miles (97 km) of primary power lines throughout the district.[371]

Crime

Washington has historically endured high crime, particularly violent offenses. The city was once described as the "murder capital" of the United States during the early 1990s.[373] The number of murders peaked in 1991 at 479, but then began to decline,[374] reaching an historic low of 88 in 2012, the lowest total since 1961.[375] In 2016, the district's Metropolitan Police Department tallied 135 homicides, a 53% increase from 2012 but a 17% decrease from 2015.[376] By 2019, citywide reports of both property and violent crimes declined from their most recent highs in the mid-1990s.[377] However, both 2021 and 2022 saw over 200 homicides each, reflecting an upward trends from prior decades.[378] In 2023, D.C. recorded 274 homicides, a 20-year high and the fifth-highest murder rate among the nation's largest cities.[379]

Many D.C. residents began to press the city government for refusing to prosecute nearly 70% of arrested offenders in 2022. After months of criticism, the rate of unprosecuted cases dropped to 56% by October 2023—albeit still higher than nine of the past 10 years and almost twice what it was in 2013.[380] In February 2024, the Council of the District of Columbia passed a major bill meant to reduce crime in the city by introducing harsher penalties for arrested offenders.[381] Rising crime and gang activities contributed to some local businesses leaving the city.[382][383]

According to a 2018 report, 67,000 residents, or about 10% of the population, are ex-convicts.[384] An estimated 2,000–2,500 offenders return to the city from prison every year.[385]

On June 26, 2008, the Supreme Court of the United States held in District of Columbia v. Heller that the city's 1976 handgun ban violated the right to keep and bear arms as protected under the Second Amendment.[386] However, the ruling does not prohibit all forms of gun control; laws requiring firearm registration remain in place, as does the city's assault weapon ban.[387]

In addition to the Metropolitan Police Department, several federal law enforcement agencies have jurisdiction in the city, including the U.S. Park Police, founded in 1791.[388]

Sister cities

Washington, D.C., has fifteen official sister city agreements. Each of the listed cities is a national capital except for Sunderland, which includes the town of Washington, the ancestral home of George Washington's family.[389] Paris and Rome are each formally recognized as a partner city due to their special one sister city policy.[390] Listed in the order each agreement was first established, they are:

Bangkok, Thailand (1962, renewed 2002 and 2012)

Bangkok, Thailand (1962, renewed 2002 and 2012) Dakar, Senegal (1980, renewed 2006)

Dakar, Senegal (1980, renewed 2006) Beijing, China (1984, renewed 2004 and 2012)

Beijing, China (1984, renewed 2004 and 2012) Brussels, Belgium (1985, renewed 2002 and 2011)

Brussels, Belgium (1985, renewed 2002 and 2011) Athens, Greece (2000)

Athens, Greece (2000) Paris, France (2000 as a friendship and cooperation agreement, renewed 2005)[390][391]

Paris, France (2000 as a friendship and cooperation agreement, renewed 2005)[390][391] Pretoria, South Africa (2002, renewed 2008 and 2011)

Pretoria, South Africa (2002, renewed 2008 and 2011) Seoul, South Korea (2006)

Seoul, South Korea (2006) Accra, Ghana (2006)

Accra, Ghana (2006) Sunderland, United Kingdom (2006, renewed 2012)[389]

Sunderland, United Kingdom (2006, renewed 2012)[389] Rome, Italy (2011, renewed 2013)[390]

Rome, Italy (2011, renewed 2013)[390] Ankara, Turkey (2011)

Ankara, Turkey (2011) Brasília, Brazil (2013)

Brasília, Brazil (2013) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2013)[392]

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2013)[392] San Salvador, El Salvador (2018)

San Salvador, El Salvador (2018)

People

See also

- Index of Washington, D.C.–related articles

- Outline of Washington, D.C.

- USS District of Columbia

Explanatory notes

- ^ By 1790, the Southern states had largely repaid their overseas debts from the Revolutionary War. The Northern states had not, and wanted the federal government to take over their outstanding liabilities. Southern Congressmen agreed to the plan in return for establishing the new national capital at their preferred site on the Potomac River.[30]

- ^ The Residence Act allowed the President to select a location within Maryland as far east as the Anacostia River. However, Washington shifted the federal territory's borders to the southeast and rotated them to include Alexandria at the district's southern tip. In 1791, Congress amended the Residence Act to approve the new site, including territory ceded by Virginia.[31]

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- NW from January 1872 to June 1945, and at Reagan National Airport since July 1945.[99]

- ^ Apportionment totals are collected by combining Resident and Overseas population. (For D.C., this is 689545 residents and 1988 overseas population.)

- ^ Until 1890, the Census Bureau counted the City of Washington, Georgetown, and unincorporated portions of Washington County as three separate areas. The data provided in this article from before 1890 are calculated as if the District of Columbia were a single municipality as it is today. Population data for each city prior to 1890 are available.[132]

- ^ a b From 15% sample

- ^ The territories of the United States have the highest poverty rates in the United States.[158]

- ^ These figures count adherents, meaning all full members, their children, and others who regularly attend services. In all of the District, 55% of the population is adherent to any particular religion.

- ^ The titles listed in the table are for the MLS Cup. Other D.C. United honors include the Supporters' Shield: 1997, 1999, 2006, 2007; CONCACAF Champions Cup: 1998; Copa Interamericana: 1998; and Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup: 1996, 2008, 2013.

References

- ^ Imhoff, Gary (October 1999). "Our Official Songs". DC Watch. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ^ Councilmembers Archived March 20, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Washington, D.C. Accessed March 20, 2023. "Thirteen Members make up the Council: a representative elected from each of the eight wards; and five members, including the Chairman, elected at-large."

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Washington city, District of Columbia". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties in District of Columbia: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023 (CO-EST2023-POP-11)". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 18, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Metropolitan Statistical Areas in the United States and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023 (CBSA-MET-EST2023-POP)". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ "Demonyms for people from the USA". The Geography Site. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ "Demonym". addis.com. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product by County and Metropolitan Area, 2022" (PDF). Bureau of Economic Analysis. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 13, 2023. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ D.C.'s New (771) Area Code Will Start Being Assigned In November Archived April 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine(Retrieved April 26, 2021, from DCist.com)

- ^ 771 will be new D.C. area code, supplementing venerable 202 Archived November 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine(Retrieved April 26, 2021, from Washington Post)

- ^ "Introduction: Where Oh Where Should the Capital Be?". WHHA. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ^ "Washington, D.C. History F.A.Q." The Historical Society of Washington, D.C. May 27, 2014. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "Father of His Country". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. Archived from the original on July 13, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ Broder, David S. (February 18, 1990). "Nation's Capital in Eclipse as Pride and Power Slip Away". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

In the days of the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan and the creation of NATO, [Clark Clifford] said, we saved the world, and Washington became the capital of the world.

- ^ "Washington, DC Visitor Research". washington.org. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ^ "America's 10 most visited cities" Archived June 14, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, World Atlas, November 6, 2023

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica. Archivedfrom the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. Archivedfrom the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Vasilogambros, Matt (December 30, 2013). "D.C. Has More People Than Wyoming and Vermont, Still Not a State". The Atlantic. National Journal. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV". U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-888028-04-1. Archivedfrom the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ "October 6, 1783". Journals of the Continental Congress. Library of Congress: American Memory: 647. October 1783. Archived from the original on January 15, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ "October 7, 1783". Journals of the Continental Congress. Library of Congress: American Memory: 654. October 1783. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ Madison, James. "The Federalist No. 43". The Independent Journal. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ Crew, Harvey W.; Webb, William Bensing; Wooldridge, John (1892). "IV. Washington Becomes The Capital". Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, OH: United Brethren Publishing House. p. 66. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Constitution of the United States". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on August 19, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Crew, Harvey W.; Webb, William Bensing; Wooldridge, John (1892). Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, OH: United Brethren Publishing House. p. 124.

- ^ a b Crew, Harvey W.; Webb, William Bensing; Wooldridge, John (1892). Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, OH: United Brethren Publishing House. pp. 89–92.

- ^ "Georgetown Historic District". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 2, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ "Alexandria's History". Alexandria Historical Society. Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved April 4, 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-06-084238-3. Archivedfrom the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia". BoundaryStones.org. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ Salentri, Mia (July 21, 2020). "How many buildings in DC were built by slaves?". WUSA. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

{{cite news}}: Text "The Q&A" ignored (help) - ^ Davis, Damara (2010). "Slavery and Emancipation in the Nation's Capital". Prologue Magazine. Vol. 42, no. 1 (Spring ed.). U.S. National Archives. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ Crew, Harvey W.; Webb, William Bensing; Wooldridge, John (1892). Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, OH: United Brethren Publishing House. p. 101. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ "Get to Know D.C." Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "The Senate Moves to Washington". United States Senate. February 14, 2006. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ^ Tom (July 24, 2013). "Why Is Washington, D.C. Called the District of Columbia?". Ghosts of DC. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Crew, Harvey W.; Webb, William Bensing; Wooldridge, John (1892). "IV. Permanent Capital Site Selected". Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House. p. 103. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Statement on the subject of The District of Columbia Fair and Equal Voting Rights Act" (PDF). American Bar Association. September 14, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ "Saving History: Dolley Madison, the White House, and the War of 1812". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "A Brief Construction History of the Capitol". Architect of the Capitol. Archived from the original on December 10, 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ Washington History: 54–82. Archived from the original(PDF) on January 18, 2009. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ Greeley, Horace (1864). The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States. Chicago: G. & C.W. Sherwood. pp. 142–144.

- ^ "Compromise of 1850". Library of Congress. September 21, 2007. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b Dodd, Walter Fairleigh (1909). The government of the District of Columbia. Washington, D.C.: John Byrne & Co. pp. 40–45.

- ^ a b "Ending Slavery in the District of Columbia". D.C. Office of the Secretary. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. September 13, 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-06-084238-3. Archivedfrom the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "An Act to provide a Government for the District of Columbia". Statutes at Large, 41st Congress, 3rd Session. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

- ^ Wilcox, Delos Franklin (1910). Great cities in America: their problems and their government. The Macmillan Company. pp. 27–30.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-9353-7.

- ^ a b Tindall, William (1907). Origin and government of the District of Columbia. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 26–28.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4195-9373-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-4727-5. Archivedfrom the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Home Rule or House Rule? Congress and the Erosion of Local Governance in the District of Columbia Archived August 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine by Michael K. Fauntroy, University Press of America, 2003 at Google Books, page 94

- ISBN 978-0-7385-1636-3. Archivedfrom the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Twenty-third Amendment". CRS Annotated Constitution. Legal Information Institute (Cornell University Law School). Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ Schwartzman, Paul; Robert E. Pierre (April 6, 2008). "From Ruins To Rebirth". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- ^ "District of Columbia Home Rule Act". Government of the District of Columbia. February 1999. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ Mathews, Jay (October 11, 1999). "City's 1st Mayoral Race, as Innocent as Young Love". The Washington Post. p. A1. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ Flynn, Meagan (January 24, 2023). "D.C. leaders herald Senate statehood bill despite steep odds". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ "District of Columbia: 2010" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. June 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ^ "Facts & FAQs". Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. Archived from the original on August 13, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ Grant III, Ulysses Simpson (1950). "Planning the Nation's Capital". Records of the Columbia Historical Society. 50: 43–58.

- JSTOR 40067664.

- ^ "C&O Canal National Historic Park: History & Culture". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ^ Dvorak, Petula (April 18, 2008). "D.C.'s Puny Peak Enough to Pump Up 'Highpointers'". The Washington Post. pp. B01. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-89587-279-1. Archivedfrom the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Science in Your State: District of Columbia". United States Geological Survey. July 30, 2007. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ Reilly, Mollie (May 12, 2012). "Washington's Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales—Some of Which Are True". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Kelly, John (April 1, 2012). "Washington Built on a Swamp? Think Again". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- The Trust for Public Land. 2011. Archived(PDF) from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ^ "ParkScore". www.parkscore.tpl.org. Archived from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ "Comparison of Federally Owned Land with Total Acreage of States" (PDF). Bureau of Land Management. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ^ "Rock Creek Park". Geology Fieldnotes. National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ^ "District of Columbia". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ "FY12 Performance Plan" (PDF). D.C. Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. National Arboretum History and Mission". United States National Arboretum. October 16, 2007. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- ^ Peterson, Adam (September 22, 2016), English: Trewartha climate types for the contiguous United States, archived from the original on March 30, 2019, retrieved March 8, 2019

- ^ "Hardiness Zones". Arbor Day Foundation. 2006. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- Washington Post. Archivedfrom the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "Average Conditions: Washington DC, USA". BBC Weather. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Iovino, Jim (June 6, 2010). "Severe Storm Warnings, Tornado Watches Expire". NBCWashington.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Watson, Barbara McNaught (November 17, 1999). "Washington Area Winters". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ Ambrose, Kevin; Junker, Wes (January 23, 2016). "Where Snowzilla fits into D.C.'s top 10 snowstorms". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ Heidorn, Keith C. (January 1, 2012). "The Washington and Jefferson Snowstorm of 1772". The Weather Doctor. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-9786280-0-0. Archivedfrom the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Vogel, Steve (June 28, 2006). "Bulk of Flooding Expected in Old Town, Washington Harbour". The Washington Post. p. B02. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ^ a b "WMO Climate Normals for WASHINGTON DC/NATIONAL ARPT VA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Samenow, Jason (June 29, 2012). "Washington, D.C. shatters all-time June record high, sizzles to 104". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ a b "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ Grieser, Justin; Livingston, Ian (November 8, 2017). "The first freeze is coming Saturday and, for most of the D.C. area, it's historically late Archived May 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". The Washington Post.

- ^ Livingston, Ian; Grieser, Justin (April 3, 2018). "When will the last freeze happen around the D.C. region, and when is it safe to plant? Archived April 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine" The Washington Post.

- ^ "Threaded Station Extremes". threadex.rcc-acis.org.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Matt (April 1, 2015). "April outlook: Winter be gone! First half of month looks warmer than average". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

For reference, here are the 30-year climatology benchmarks for Reagan National Airport for April, along with our projections for the coming month:...Average snowfall: Trace; Forecast: 0 to trace

- ^ "Washington, DC - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Coleman, Christopher Bush (1920). Indiana Magazine of History. Indiana Historical Society. p. 109. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The L'Enfant and McMillan Plans". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- from the original on November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Map 1: The L'Enfant Plan for Washington". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ^ Crew, Harvey W.; Webb, William Bensing; Wooldridge, John (1892). Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, OH: United Brethren Publishing House. pp. 101–103.

- ^ a b Schwartzman, Paul (May 2, 2007). "High-Level Debate on Future of D.C." The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ a b "Layout of Washington DC". United States Senate. September 30, 2005. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Laws relating to the permanent system of highways outside of the cities of Washington and Georgetown. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1908. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Birnbaum, Jeffrey H. (June 22, 2005). "The Road to Riches Is Called K Street". The Washington Post. p. A01. Archived from the original on February 16, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ Van Dyne, Larry (February 1, 2008). "Foreign Affairs: DC's Best Embassies". Washingtonian Magazine. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ "America's Favorite Architecture". American Institute of Architects and Harris Interactive. 2007. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ^ a b "Washington, D.C., List of Sites". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson Building". Architect of the Capitol. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Denby, Grand Hotels: Reality and Illusion, 2004, p. 221–222.

- ^ "Meridian Hill Park". Tour Washington DC. November 15, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Kate (January 23, 2011). "The Thorny Path to a National Black Museum". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ Ables, Kelsey (March 25, 2021). "Brutalist buildings aren't unlovable. You're looking at them wrong". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Bisceglio, Paul. "The Story Behind Smithsonian Castle's Red Sandstone". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Old Post Office, a Standout on Pennsylvania Avenue". Streets of Washington. April 15, 2012. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ a b Ramanathan, Lavanya; Simmons, Holley (October 5, 2017). "What to expect at the Wharf, D.C.'s newest dining and entertainment hub". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Clabaugh, Jeff (September 11, 2017). "The Wharf: DC's most ambitious development project set to open". WTOP. Archived from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Dietsch, Deborah K. "Modernism's March on Washington." Washington Times. September 8, 2007.

- ^ "D.C. Architectural Stules and Where to Find Them". Neighborhoods.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Scott, Pamela (2005). "Residential Architecture of Washington, D.C., and Its Suburbs". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Old Stone House". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2011.