Wasp

| Wasp Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A social wasp, Vespula germanica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| (unranked): | Unicalcarida

|

| Suborder: | Apocrita |

| Groups included | |

| |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

| |

A wasp is any

The most commonly known wasps, such as

Wasps first appeared in the fossil record in the

Wasps have appeared in literature from

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Paraphyletic grouping

The wasps are a cosmopolitan

The term wasp is sometimes used more narrowly for members of the

Fossils

Hymenoptera in the form of Symphyta (

The Vespidae include the extinct genus

Diversity

Wasps are a diverse group, estimated at well over a hundred thousand

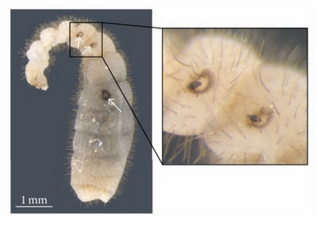

Many wasp species are parasitoids; the females deposit eggs on or in a host arthropod on which the larvae then feed. Some larvae start off as parasitoids, but convert at a later stage to consuming the plant tissues that their host is feeding on. In other species, the eggs are laid directly into plant tissues and form galls, which protect the developing larvae from predators, but not necessarily from other parasitic wasps. In some species, the larvae are predatory themselves; the wasp eggs are deposited in clusters of eggs laid by other insects, and these are then consumed by the developing wasp larvae.[10]

The largest social wasp is the

There are estimated to be 100,000 species of

-

Megascolia procer, a giant solitary species from Java in the Scoliidae. This specimen's length is 77 mm (3.0 in) and its wingspan is 115 mm (4.5 in).[b][14]

-

Megarhyssa macrurus, a parasitoid. The body of a female is 50 mm (2.0 in) long, with a c. 100 mm (3.9 in) ovipositor

-

Tarantula hawk wasp dragging the tarantula Megaphobema mesomelas to her burrow; it has the most painful sting of any wasp.[13]

Sociality

Social wasps

Of the dozens of extant wasp families, only the family

Other wasps, like Agelaia multipicta and Vespula germanica, like to nest in cavities that include holes in the ground, spaces under homes, wall cavities or in lofts. While most species of wasps have nests with multiple combs, some species, such as Apoica flavissima, only have one comb.[23] The length of the reproductive cycle depends on latitude; Polistes erythrocephalus, for example, has a much longer (up to 3 months longer) cycle in temperate regions.[24]

Solitary wasps

The vast majority of wasp species are solitary insects.[10][25] Having mated, the adult female forages alone and if it builds a nest, does so for the benefit of its own offspring. Some solitary wasps nest in small groups alongside others of their species, but each is involved in caring for its own offspring (except for such actions as stealing other wasps' prey or laying in other wasp's nests). There are some species of solitary wasp that build communal nests, each insect having its own cell and providing food for its own offspring, but these wasps do not adopt the division of labour and the complex behavioural patterns adopted by eusocial species.[25]

Adult solitary wasps spend most of their time in preparing their nests and foraging for food for their young, mostly insects or spiders. Their nesting habits are more diverse than those of social wasps. Many species dig burrows in the ground.[25] Mud daubers and pollen wasps construct mud cells in sheltered places.[26] Potter wasps similarly build vase-like nests from mud, often with multiple cells, attached to the twigs of trees or against walls.[27]

Predatory wasp species normally subdue their prey by stinging it, and then either lay their eggs on it, leaving it in place, or carry it back to their nest where an egg may be laid on the prey item and the nest sealed, or several smaller prey items may be deposited to feed a single developing larva. Apart from providing food for their offspring, no further maternal care is given. Members of the family Chrysididae, the cuckoo wasps, are kleptoparasites and lay their eggs in the nests of unrelated host species.[25]

Biology

Anatomy

Like all insects, wasps have a hard exoskeleton which protects their three main body parts, the head, the mesosoma (including the thorax and the first segment of the abdomen) and the metasoma. There is a narrow waist, the petiole, joining the first and second segments of the abdomen. The two pairs of membranous wings are held together by small hooks and the forewings are larger than the hind ones; in some species, the females have no wings. In females there is usually a rigid ovipositor which may be modified for injecting venom, piercing or sawing.[28] It either extends freely or can be retracted, and may be developed into a stinger for both defence and for paralysing prey.[29]

In addition to their large

The larvae of wasps resemble maggots, and are adapted for life in a protected environment; this may be the body of a host organism or a cell in a nest, where the larva either eats the provisions left for it or, in social species, is fed by the adults. Such larvae have soft bodies with no limbs, and have a blind gut (presumably so that they do not foul their cell).[31]

Diet

Adult solitary wasps mainly feed on nectar, but the majority of their time is taken up by foraging for food for their carnivorous young, mostly insects or spiders. Apart from providing food for their larval offspring, no maternal care is given.[25] Some wasp species provide food for the young repeatedly during their development (progressive provisioning).[32] Others, such as potter wasps (Eumeninae)[33] and sand wasps (Ammophila, Sphecidae),[34] repeatedly build nests which they stock with a supply of immobilised prey such as one large caterpillar, laying a single egg in or on its body, and then sealing up the entrance (mass provisioning).[35]

Predatory and parasitoidal wasps subdue their prey by stinging it. They hunt a wide variety of prey, mainly other insects (including other Hymenoptera), both larvae and adults.[25] The

Some social wasps are omnivorous, feeding on fallen fruit, nectar, and carrion such as dead insects. Adult male wasps sometimes visit flowers to obtain nectar. Some wasps, such as Polistes fuscatus, commonly return to locations where they previously found prey to forage.[37] In many social species, the larvae exude copious amounts of salivary secretions that are avidly consumed by the adults. These include both sugars and amino acids, and may provide essential protein-building nutrients that are otherwise unavailable to the adults (who cannot digest proteins).[38]

Sex determination

In wasps, as in other Hymenoptera,

Inbreeding avoidance

Females of the solitary wasp parasitoid Venturia canescens can avoid mating with their brothers through kin recognition.[40] In experimental comparisons, the probability that a female will mate with an unrelated male was about twice as high as the chance of her mating with brothers. Female wasps appear to recognize siblings on the basis of a chemical signature carried or emitted by males.[40] Sibling-mating avoidance reduces inbreeding depression that is largely due to the expression of homozygous deleterious recessive mutations.[41]

Ecology

As pollinators

While the vast majority of wasps play no role in pollination, a few species can effectively transport pollen and pollinate several plant species.[42] Since wasps generally do not have a fur-like covering of soft hairs and a special body part for pollen storage (pollen basket) as some bees do, pollen does not stick to them well.[43] However it has been shown that even without hairs, several wasp species are able to effectively transport pollen, therefore contributing for potential pollination of several plant species.[44]

Pollen wasps in the subfamily

The Agaonidae (fig wasps) are the only pollinators of nearly 1000 species of figs,[43] and thus are crucial to the survival of their host plants. Since the wasps are equally dependent on their fig trees for survival, the coevolved relationship is fully mutualistic.[46]

As parasitoids

Most solitary wasps are parasitoids.[47] As adults, those that do feed typically only take nectar from flowers. Parasitoid wasps are extremely diverse in habits, many laying their eggs in inert stages of their host (egg or pupa), sometimes paralysing their prey by injecting it with venom through their ovipositor. They then insert one or more eggs into the host or deposit them upon the outside of the host. The host remains alive until the parasitoid larvae pupate or emerge as adults.[48]

The

One family of chalcidoid wasps, the Eucharitidae, has specialized as parasitoids of ants, most species hosted by one genus of ant. Eucharitids are among the few parasitoids that have been able to overcome ants' effective defences against parasitoids.[50][51][52]

As parasites

Many species of wasp, including especially the cuckoo or jewel wasps (

As predators

Many wasp lineages, including those in the families

The roughly 140 species of beewolf (Philanthinae) hunt bees, including honeybees, to provision their nests; the adults feed on nectar and pollen.[61]

As models for mimics

With their powerful stings and conspicuous

As prey

While wasp stings deter many potential predators,

-

Minute pollinating fig wasps, Pleistodontes: the trees and wasps have coevolved and are mutualistic.

-

Latina rugosa planidia (arrows, magnified) attached to an ant larva; the Eucharitidae are among the few parasitoids able to overcome the strong defences of ants.

-

TheChrysididae, such as this Hedychrum rutilans, are known as cuckoo or jewel wasps for their parasitic behaviour and metallic iridescence.

-

European beewolf Philanthus triangulum provisioning her nest with a honeybee

-

Wasp beetle Clytus arietis is a Batesian mimicof wasps.

-

Bee-eaters such asMerops apiasterspecialise in feeding on bees and wasps.

Relationship with humans

As pests

Social wasps are considered pests when they become excessively common, or nest close to buildings. People are most often stung in late summer and early autumn, when wasp colonies stop breeding new workers; the existing workers search for sugary foods and are more likely to come into contact with humans.

In horticulture

Some species of parasitic wasp, especially in groups such as

-

insect pestof tomato and other horticultural crops.

-

Tomato leaf covered with nymphs of whitefly parasitised by Encarsia formosa

In sport

Wasps RFC is an English professional rugby union team originally based in London but now playing in Coventry; the name dates from 1867 at a time when names of insects were fashionable for clubs. The club's first kit is black with yellow stripes.[76] The club has an amateur side called Wasps FC.[77]

Among the other clubs bearing the name are a basketball club in Wantirna, Australia,[78] and Alloa Athletic F.C., a football club in Scotland.[79]

In fashion

Wasps have been modelled in jewellery since at least the nineteenth century, when diamond and emerald wasp brooches were made in gold and silver settings.[80] A fashion for wasp waisted female silhouettes with sharply cinched waistlines emphasizing the wearer's hips and bust arose repeatedly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[81][82]

In literature

The Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes wrote the comedy play Σφῆκες (Sphēkes), The Wasps, first put on in 422 BC. The "wasps" are the chorus of old jurors.[83]

H. G. Wells made use of giant wasps in his novel The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth (1904):[84]

It flew, he is convinced, within a yard of him, struck the ground, rose again, came down again perhaps thirty yards away, and rolled over with its body wriggling and its sting stabbing out and back in its last agony. He emptied

both barrels into it before he ventured to go near. When he came to measure the thing, he found it was twenty-seven and a half inches across its open wings, and its sting was three inches long. ... The day after, a cyclist riding, feet up, down the hill between Sevenoaks and Tonbridge, very narrowly missed running over a second of these giants that was crawling across the roadway.[84]

Wasp (1957) is a science fiction book by the English writer Eric Frank Russell; it is generally considered Russell's best novel.[86] In Stieg Larsson's book The Girl Who Played with Fire (2006) and its film adaptation, Lisbeth Salander has adopted her kickboxing ringname, "The Wasp", as her hacker handle and has a wasp tattoo on her neck, indicating her high status among hackers, unlike her real world situation, and that like a small but painfully stinging wasp, she could be dangerous.[87]

Parasitoidal wasps played an indirect role in the nineteenth-century evolution debate. The Ichneumonidae contributed to Charles Darwin's doubts about the nature and existence of a well-meaning and all-powerful Creator. In an 1860 letter to the American naturalist Asa Gray, Darwin wrote:

I own that I cannot see as plainly as others do, and as I should wish to do, evidence of design and beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.[88]

In military names

With its powerful sting and familiar appearance, the wasp has given its name to many ships, aircraft and military vehicles.[89] Nine ships and one shore establishment of the Royal Navy have been named HMS Wasp, the first an 8-gun sloop launched in 1749.[90] Eleven ships of the

See also

- Characteristics of common wasps and bees

- Bee and wasp stings

- Schmidt sting pain index

- Fear of wasps (spheksophobia)

Notes

- ^ Methods to estimate species diversity include extrapolating the rate of species descriptions by subfamily (as in the Braconidae) until zero is reached; and extrapolating geographically from the species distribution of well-studied taxa to the group of interest (say, the Braconidae). Dolphin et al found a correlation between the predicted numbers of undescribed species by these two methods, doubling or tripling the number of species in the group.[9]

- ^ Specimen measured from photograph.

References

- ^ Broad, Gavin (25 June 2014). "What's the point of wasps?". Natural History Museum. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Wasp". National Geographic. 9 November 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010.

- S2CID 230835.

- ISBN 978-1-4615-6915-2.

- ^ "World's oldest fig wasp fossil proves that if it works, don't change it". University of Leeds. 15 June 2010. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ Poinar, G. (2005). "Fossil Trigonalidae and Vespidae (Hymenoptera) in Baltic amber". Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 107 (1): 55–63.

- hdl:2445/36428.

- PMID 22303121.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-00047-3.

- ISBN 978-1-84537-734-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4027-5623-8.

Pepsis heros, which has a body length of up to 5.7cm (2 1/4 in) and a maximum wingspan of 11.4 cm (4 1/2 in).

- ^ a b Williams, David B. "Tarantula Hawk". DesertUSA. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ S2CID 30936410. Measurement scale on Figure 1.

- ^ Betrem, J. G.; Bradley, J. Chester (1964). "Annotations on the genera Triscolia, Megascolia and Scolia (Hymenoptera, Scoliidae)". Zoologische Mededelingen. 39 (43): 433–444.

- ISBN 978-1-4832-6370-0.

- ^ Cranshaw, W. (5 August 2014). "Pigeon Tremex Horntail and the Giant Ichneumon Wasp". Colorado State University Extension. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- .

- ^ Ward, D.F.; Schnitzler, F.R. (2013). "Ichneumonidae: Eucerotinae: Euceros Gravenhorst 1829". Landcare Research. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Westlake, Casey (13 March 2014). "More to biological diversity than meets the eye: Specialization by insect species is the key". Iowa Now. University of Iowa. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- S2CID 13911928.

- ^ Carlos A. Martin P.; Anthony C. Bellotti (1986). "Biologia y comportamiento de Polistes erythrocephalus" [Biology and behavior of Polistes erythrocephalus] (PDF). Acta Agron (in Spanish). 36 (1): 63–76. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- S2CID 86577862.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8014-3721-2.

- ^ Houston, Terry (October 2013). "Slender mud-dauber wasps: genus Sceliphron". Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Grissell, E. E. (April 2007). "Potter wasps of Florida". University of Florida. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Hymenoptera: ants, bees and wasps". Insects and their allies. CSIRO. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-82149-0.

- PMID 18088974.

- ISBN 978-0-19-510033-4.

- .

- ^ Grissell, E. E. "Potter Wasps of Florida". University of Florida / IFAS. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- JSTOR 4534782.

- .

- ^ "Spider Wasps". Australian Museum. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- PMID 10761573.

- ISBN 978-0-674-00089-6.

- S2CID 54687768.

- ^ PMID 20976063.

- S2CID 771357.

- ^ Sühs, R.B.; Somavilla, A.; Köhler, A; Putzke, J. (2009). "Vespídeos (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) vetores de pólen de Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae), Santa Cruz do Sul, RS, Brasil" [Pollen vector wasps (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae), Santa Cruz do Sul, RS, Brazil]. Brazilian Journal of Biosciences (in Portuguese). 7 (2): 138–143.

- ^ a b "Wasp Pollination". USDA Forest Service. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ Sühs; Somavilla; Putzke; Köhler (2009). "Pollen vector wasps (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) of Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae), Santa Cruz do Sul, RS, Brazil". Brazilian Journal of Biosciences. 7 (2): 138–143 – via ABEC.

- ^ Tepidino, Vince. "Pollen Wasps". USDA Forest Service. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- PMID 15851680.

- ^ Sekar, Sandhya (22 May 2015). "Parasitoid wasps may be the most diverse animal group". BBC. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-412-58350-6.

- ^ Sezen, Uzay (24 March 2015). "Giant Ichneumon Wasp (Megarhyssa macrurus) Ovipositing". Nature Documentaries.org. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-8133-8615-7.

- .

- .

- PMID 15019524.

- ^ O'Neill, Kevin M. (2001). Solitary Wasps: Behavior and Natural History. Cornell University Press. p. 129.

- ^ Deslippe, Richard (2010). "Social Parasitism in Ants". Nature Education Knowledge.

- ^ Emery, C. (1909). "Über den Ursprung der dulotischen, parasitischen und myrmekophilen Ameisen". Biologisches Centralblatt (in German). 29: 352–362.

- S2CID 53048610.

- ^ Dvorak, L. (2007). "Parasitism of Dolichovespula norwegica by D. adulterina (Hymenoptera: Vespidae)" (PDF). Silva Gabreta. 13 (1): 65–67. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-08-053301-8.

- ^ "Biology of the European beewolf (Philanthus triangulum, Hymenoptera, Crabronidae)". Evolutionary Ecology. University of Regensburg. 5 June 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-582-44132-3.

- ISBN 978-1-85391-186-6.

- ^ "Hornet attacks kill dozens in China". The Guardian. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- ^ "Roadrunners". Avian Web. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Gross, Bob (19 September 2017). "Close encounters with stinging insects common in the fall". Times Herald. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Boyles, Margaret (18 August 2021). "Yellow Jacket Alert: Taking the Sting Out of Fall". The Old Farmer's Almanac. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Hayes, Kim (11 October 2017). "What's That Buzz? Fall may bring more aggressive hornets and wasps". AARP. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "Wasps". British Pest Control Association. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Allergy to Wasp and Bee Stings". Allergy UK. Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "New wasp parasite being studied". The Royal Society of New Zealand. 20 April 2000. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Hoddle, Mark. "Encarsia formosa". Cornell University. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Aphid Predators". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4831-4184-8.

- ^ "History 1867–1930 London Wasps". Wasps.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Wasps Football Club". Pitcher. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Wantirna Wasps Basketball Club". Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Alloa Athletic Football Club". Scottish Professional Football League. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ "Diamond and emerald wasp brooch by Fontanna". A La Vieille Russie. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

Crown rose diamond and emerald wasp brooch set in silver and gold. By Fontana French, ca. 1875. Width: 3 inches. $46,500

- ^ Kunzle, David. "Fashion and Fetishism". Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Klingerman, Katherine Marie (May 2006). Binding Femininity: The Effects of Tightlacing on the Female Pelvis (PDF). University of Vermont (MA Thesis). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Ancient Greece – Aristophanes – The Wasps". Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ a b Wells, H. G. (1904). Food of the Gods. Macmillan.

- ISBN 978-0896599314.

- ISBN 978-0-575-07095-0.

- ISBN 978-1-936661-35-0.

- ^ "Letter 2814 — Darwin, C. R. to Gray, Asa". 22 May 1860. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ a b "USS Wasp. History". United States Navy. Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- ISBN 978-1-56311-404-5.

- ^ Jentz, Thomas L.; Doyle, Hilary Louis (2011). Panzer Tracts No. 23: Panzer Production From 1933 to 1945. Panzer Tracts.

- ISBN 9781586637620.

- ISBN 978-0-85177-847-1.

- ^ "US Air Force Wasp III Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

Sources

- Ross, Kenneth G. (1991). The Social Biology of Wasps. Cornell Press. ISBN 978-0-801-49906-7.

External links

- Differences between Bees and Wasps

- Natural History Museum – Wasps: If you can't love them, at least admire them

- N.I.H. Medline Encyclopedia – Insect bites and stings

- Waspweb

- DermNet arthropods/bites

![Megascolia procer, a giant solitary species from Java in the Scoliidae. This specimen's length is 77 mm (3.0 in) and its wingspan is 115 mm (4.5 in).[b][14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/Megascolia_procer_MHNT_dos.jpg/394px-Megascolia_procer_MHNT_dos.jpg)

![Tarantula hawk wasp dragging the tarantula Megaphobema mesomelas to her burrow; it has the most painful sting of any wasp.[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Wasp_with_Orange-kneed_tarantula.JPG/393px-Wasp_with_Orange-kneed_tarantula.JPG)