Weird fiction

| Fantasy |

|---|

| Media |

|

| Genre studies |

|

| Subgenres |

|

| Fandom |

| Categories |

Weird fiction is a subgenre of

Weird fiction often attempts to inspire

Definitions

John Clute defines weird fiction as a term "used loosely to describe fantasy, supernatural fiction and horror tales embodying transgressive material".[5] China Miéville defines it as "usually, roughly, conceived of as a rather breathless and generically slippery macabre fiction, a dark fantastic ('horror' plus 'fantasy') often featuring nontraditional alien monsters (thus plus 'science fiction')".[1] Discussing the "Old Weird Fiction" published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock says, "Old Weird fiction utilises elements of horror, science fiction and fantasy to showcase the impotence and insignificance of human beings within a much larger universe populated by often malign powers and forces that greatly exceed the human capacities to understand or control them."[2] Jeff and Ann VanderMeer describe weird fiction as a mode of literature, usually appearing within the horror fiction genre, rather than a separate genre of fiction in its own right.[6]

History

Although the term "weird fiction" did not appear until the 20th century, Edgar Allan Poe is often regarded as the pioneering author of weird fiction. Poe was identified by Lovecraft as the first author of a distinct type of supernatural fiction different from traditional Gothic literature, and later commentators on the term have also suggested Poe was the first "weird fiction" writer.[1][2] Sheridan Le Fanu is also seen as an early writer working in the sub-genre.[1]

Literary critics in the nineteenth century would sometimes use the term "weird" to describe supernatural fiction. For instance, the Scottish Review in an 1859 article praised Poe,

In the late nineteenth century, a number of British writers associated with the Decadent movement wrote what was later described as weird fiction. These writers included Machen, M. P. Shiel, Count Eric Stenbock, and R. Murray Gilchrist.[9] Other pioneering British weird fiction writers included Algernon Blackwood,[10] William Hope Hodgson, Lord Dunsany,[11] Arthur Machen,[12] and M. R. James.[13]

The American

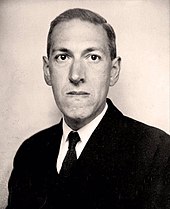

H. P. Lovecraft popularised the term "weird fiction" in his essays.[1] In "Supernatural Horror in Literature", Lovecraft gives his definition of weird fiction:

The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain—a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.

S. T. Joshi describes several subdivisions of the weird tale: supernatural horror (or fantastique), the ghost story, quasi science fiction, fantasy, and ambiguous horror fiction and argues that "the weird tale" is primarily the result of the philosophical and aesthetic predispositions of the authors associated with this type of fiction.[17][18]

Although Lovecraft was one of the few early 20th-century writers to describe his work as "weird fiction",

Notable authors

The following notable authors have been described as writers of weird fiction. They are listed alphabetically by last name, and organised by the time period when they began to publish weird fiction.

Before 1940

- Ryūnosuke Akutagawa[3]

- Roberto Arlt

- R. H. Barlow

- E. F. Benson[20]

- Ambrose Bierce[22]

- Algernon Blackwood[23]

- Robert Bloch

- Marjorie Bowen[24]

- John Buchan[25]

- Mikhail Bulgakov

- Leonora Carrington[3]

- Robert W. Chambers[1]

- Leonard Cline

- Mary Elizabeth Counselman[3]

- Walter de la Mare[20]

- August Derleth

- Lord Dunsany

- E. R. Eddison[20]

- Guy Endore[26]

- Robert Murray Gilchrist[27]

- Stefan Grabiński[28]

- Alexander Grin

- Nikolai Gogol

- Sakutarō Hagiwara

- L. P. Hartley[20]

- W. F. Harvey

- Nathaniel Hawthorne[29]

- Lafcadio Hearn

- Georg Heym

- William Hope Hodgson[20]

- E. T. A. Hoffmann[30]

- Robert E. Howard[20]

- Carl Jacobi[1]

- Henry James

- M. R. James[1]

- Franz Kafka[3]

- C. F. Keary[31]

- Alfred Kubin

- Henry Kuttner

- Vernon Lee[32]

- Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu[1]

- Fritz Leiber

- David Lindsay[33]

- Frank Belknap Long

- H. P. Lovecraft

- Arthur Machen

- Daphne du Maurier

- Abraham Merrit[1]

- Gustav Meyrink

- C. L. Moore[1]

- Fitz James O'Brien

- Oliver Onions[20]

- Thomas Owen[34]

- Edgar Allan Poe[30]

- Horacio Quiroga

- Edogawa Ranpo

- Jean Ray

- Tod Robbins[35]

- Eric Frank Russell[36]

- Bruno Schulz[3]

- Marcel Schwob

- Walter Scott

- Mary Shelley

- M. P. Shiel[20]

- William Milligan Sloane III

- Clark Ashton Smith[20]

- Eric Stenbock[37]

- Francis Stevens[3]

- Bram Stoker

- Theodore Sturgeon

- Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy

- E. H. Visiak[1]

- H. Russell Wakefield

- Hugh Walpole

- Evangeline Walton

- Donald Wandrei[5]

- Howard Wandrei

- H. G. Wells[1]

- Edward Lucas White[1]

- Henry S. Whitehead[38]

1940–1980

- Robert Aickman[3]

- J. G. Ballard[3]

- Charles Beaumont[3]

- Olympe Bhely-Quenum[3]

- Jerome Bixby[3]

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Ray Bradbury[3]

- William S. Burroughs[3]

- Octavia E. Butler[3]

- Ramsey Campbell[3]

- Angela Carter[3]

- Julio Cortázar[39]

- Philip K. Dick[3]

- Thomas M. Disch

- Harlan Ellison[3]

- Philippe Druillet

- Philip José Farmer

- Shirley Jackson[20]

- Stephen King[3]

- Tanith Lee[3]

- George R. R. Martin[3]

- Richard Matheson[3]

- Augusto Monterroso

- Michael Moorcock[3]

- Haruki Murakami

- Joyce Carol Oates[3]

- Mervyn Peake[3]

- Joanna Russ[3]

- Sarban[5]

- William Sansom[3]

- Claude Seignolle[30]

- Margaret St. Clair[3]

- Peter Straub[3]

- James Tiptree, Jr.[3]

- Amos Tutuola[3]

- Jack Vance

- Karl Edward Wagner[3]

- Manly Wade Wellman

- Gahan Wilson[40]

- Gene Wolfe[3]

1980–present

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

- Daniel Abraham

- Michal Ajvaz

- Nathan Ballingrud

- Clive Barker[3][41]

- Laird Barron

- David Beauchard

- K. J. Bishop[3]

- James P. Blaylock

- Giannina Braschi

- Poppy Z. Brite

- Kevin Brockmeier

- Charles Burns

- Jonathan Carroll[5]

- David F. Case

- Michael Chabon

- Michael Cisco[3]

- Nancy Collins

- Brendan Connell

- Andrey Dashkov

- Mark Z. Danielewski

- Junot Diaz

- Doug Dorst

- Michael Dougherty

- Hal Duncan[1]

- Katherine Dunn[1]

- Dennis Etchison

- Brian Evenson

- Paul Di Filippo

- Jeffrey Ford

- Karen Joy Fowler[3]

- Neil Gaiman

- Felix Gilman

- Jean Giraud

- Elizabeth Hand[3]

- M. John Harrison[3]

- Brian Hodge

- Wolfgang Hohlbein

- Simon Ings[41]

- Junji Ito

- Alejandro Jodorowsky

- Stephen Graham Jones

- Caitlín R. Kiernan[1]

- T. E. D. Klein[20]

- Kathe Koja[3]

- Leena Krohn

- Marc Laidlaw

- Jay Lake

- Margo Lanagan

- John Langan

- Joe R. Lansdale

- Deborah Levy

- Thomas Ligotti[1]

- Kelly Link

- Brian Lumley

- Carmen Maria Machado

- Ilya Masodov

- Michael McDowell

- Lincoln Michel

- China Miéville

- Sarah Monette

- Grant Morrison[1]

- Reza Negarestani

- Scott Nicolay

- Jeff Noon

- David Ohle

- Ben Okri

- Otsuichi

- Helen Oyeyemi

- Benoît Peeters

- Cameron Pierce

- Rachel Pollack

- Tim Powers

- W. H. Pugmire

- Joseph S. Pulver, Sr.

- Cat Rambo

- Alistair Rennie

- Matt Ruff

- Sofia Samatar

- Andrzej Sarwa

- François Schuiten

- Lucius Shepard

- William Browning Spencer

- Simon Strantzas

- Charles Stross

- Oh Seong-dae

- R. L. Stine

- Steph Swainston[3]

- Jeffrey Thomas

- Karin Tidbeck

- Lisa Tuttle

- Steven Utley

- Jeff VanderMeer

- Aliya Whiteley

- Liz Williams

- Chet Williamson[5]

- F. Paul Wilson[5]

- Christopher Howard Wolf

New Weird

See also

- Cosmic horror

- Dark fantasy

- List of genres

- Lovecraftian horror

- Occult detective

- Surrealism

- Urban fantasy

Notes

- ^ ISBN 0-415-45378-X

- ^ ISBN 9781137523457

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq VanderMeer, Ann and Jeff (6 May 2012). "The Weird: An Introduction". Weird Fiction Review. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Nunnally, Mya (19 October 2017). "A Beginner's Guide to the New Weird Genre". BOOK RIOT. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f John Clute, "Weird Fiction Archived 2018-09-30 at the Wayback Machine", in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, 1997. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ISBN 9783319905266

- ^ Machin, p. 22

- ^ Machin, p. 14

- ^ Machin, p. 78

- ^ ISBN 0-292-79050-3.

- ^ Joshi 1990, p. 42

- ^ Joshi 1990, p. 12

- ^ Joshi 1990, p. 133

- ^ Machin, p. 222-5

- ISBN 978-1726443463

- ISBN 9780517693315

- ISBN 9780809531226.

- ^ Joshi 1990, pp. 7–10

- ISBN 0-06-621392-4., pp. 217-18

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Joshi 1990, p. 231

- ISBN 0-8125-1660-5

- ^ Joshi 1990, p. 143

- ^ Joshi 1990, p. 87

- ISBN 9781557420046

- ^ Machin 2018, pp. 163–219

- ^ Jerry L. Ball, "Guy Endore's The Werewolf of Paris: The Definitive Werewolf Novel?" Studies in Weird Fiction, no. 17, summer 1995, pp. 2–12

- ^ Machin 2018, pp. 99–101

- ^ Timothy Jarvis, 101 Weird Writers #45 — Stefan Grabiński Archived 2018-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, Weird Fiction Review, December 20, 2016. Retrieved September 1 2018.

- ^ "Twice-Told Tales...and Mosses From an Old Manse (1846; 23s) include most of Hawthorne's weird fiction. " Michael Ashley, Who's Who in Horror and Fantasy Fiction.

Taplinger Publishing Company, 1978, p. 90. ISBN 9780800882754

- ^ a b c "13 Supreme Masters of Weird Fiction" by R.S Hadji.Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone Magazine, May–June 1983, p. 84

- ISBN 9781987512564

- ISBN 9780816118328

- ^ Gordon, Joan (2003). "Reveling in Genre: An Interview with China Miéville". Science Fiction Studies. 30 (91). Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Gauvin, Edward (November 2011). "Kavar the Rat". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Tod Robbins (Clarence Aaron Robbins, 1888-1949) specialized in weird fiction throughout his lengthy writing career." Christie, Gene. The People of the Pit, and other early horrors from the Munsey Pulps.

Normal, IL : Black Dog Books, 2010. ISBN 9781928619963(p. 201).

- ^ "Although Eric Frank Russell wrote a relatively small number of novels, he published several major collections...More recently, Midnight House collected much of his best horror and weird fiction in Darker Tides in 2006". O'Neill, John. Vintage Treasures: Sentinels of Space by Eric Frank Russell / The Ultimate Invader edited by Donald Wollheim Black Gate, 13 April 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Machin 2018, pp. 101–114

- ISBN 9781476604244

- ^ Nolen, Larry. "Weirdfictionreview.com's 101 Weird Writers: #3 – Julio Cortázar". Weird Fiction Review. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ISBN 9781434403360.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-892391-55-1. Archivedfrom the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

References

- ISBN 0-292-79050-3.

External links

- H. P. Lovecraft, "Notes on Writing Weird Fiction"

- WeirdTalesMagazine.com, the original magazine of weird fiction

- WeirdFictionReview.com, a website by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer dedicated to the genre