1873 Vienna World's Fair

| 1873 Exposition Universelle (1867) in Paris | |

|---|---|

| Next | Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia |

The 1873 Vienna World's Fair (

History

As well as being a chance to showcase Austro-Hungarian industry and culture, the World's Fair in Vienna commemorated

Facilities

There were almost 26,000 exhibitors[3] housed in different buildings that were erected for this exposition, including the Rotunda (Rotunde), a large circular building in the great park of Prater designed by the Scottish engineer John Scott Russell. (The fair Rotunda was destroyed by fire on 17 September 1937.)

Russian pavilion

The Russian pavilion had a naval section designed by Viktor Hartmann. Exhibits included models of the Port of Rijeka[4] and the Illés Relief model of Jerusalem.[5]

Japanese pavilion

The

Forty-one Japanese officials and government interpreters, as well as six Europeans in Japanese employ, came to Vienna to oversee the pavilion and the fair's cultural events. 25 craftsmen and gardeners created the main pavilion, as well as a full

-

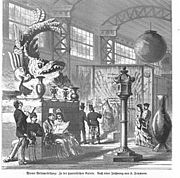

A Western engraving of the Japanese craftsmen constructing the pavilion and garden

-

The foyer of the Japanese pavilion, from the Japanese report on the fair compiled under Tsunetami Sano

-

The interior of the pavilion, including the golden shachi, from the Illustrated Times (Illustrirte Zeitung)

-

Part of the Japanese display, as seen from one of the Ottoman minarets

Ottoman pavilion

The Ottoman pavilion included a gallery of mannequins wearing the traditional costumes of many of the varied ethnic groups of the Ottoman Empire. To supplement the cases of costumes, Osman Hamdi and de Launay created a photographic book of Ottoman costumes, the Elbise-i 'Osmaniyye (Les costumes populaires de la Turquie), with photographs by Pascal Sébah. The photographic plates of the Elbise depicted traditional Ottoman costumes, commissioned from artisans working in the administrative divisions (vilayets) of the Empire, worn by men, women, and children who resembled the various ethnic and religious types of the empire, though the models were all found in Istanbul. The photographs are accompanied by texts describing the costumes in detail and commenting on the rituals and habits of the regions and ethnic groups in question.[8]

-

Sultan Ahmed Fountain reconstructed for the fair

Italian pavilion

Professor Lodovico Brunetti of

New Zealand pavilion

New Zealand was represented at the 1873

Gallery

-

Main entrance to the fair with the Rotunda behind

-

Naval section of the Russian pavilion

-

The Illés Relief

-

Swedish folk costumes displayed at the exposition

See also

- New Zealand Interprovincial Exhibition (preparatory event in New Zealand)

- Yushima Seidō Exposition (preparatory event in Japan)

References

Citations

- ^ a b TNM (2019), Yushima Seido Exposition.

- ^ a b c d e f g TNM (2019), The World's Fair in Viena: The Origin of the Japanese Modern Museum.

- ^ Lowe, Charles (1892). Four national exhibitions in London and their organiser. With portraits and illustrations (1892). London, T. F. Unwin. p. 28. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ "PATCHing the city 09". City of Rijeka. 2009. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Tower of David Museum of the History of Jerusalem | Model of Jerusalem in the 19th Century". Towerofdavid.org.il. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ TNM (2019), The Jinshin Survey: Research of Cultural Properties.

- ^ Trencsényi, Balász; Kopečk, Michal (2007). "Osman Hamdi Bey and Victor Marie de Launay: The Popular Costumes of Turkey in 1873". Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945). National Romanticism: Formation of National Movements. Vol. II. Budapest; New York: Central European University Press. pp. 174–180.

- ^ JSTOR 1523332.

- ISBN 0520074947.

- ISBN 0-520-20816-1.

- ^ Wolfe, Richard (11 Nov 2019). "International Exhibitions". Auckland Museum. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

Bibliography

- "Official site". Tokyo National Museum. 2019.. (in English)