Western culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, or Western society, includes the diverse

Western culture is characterized by a host of artistic, philosophic, literary and

While traditionally shunned as a mainspring of Western civilization in favour of early Aegean cultures, the

Western culture continued to develop with the Christianization of European society during the Middle Ages, the reforms triggered by the

Terminology

"The West" as a geographical area is unclear and undefined. There is some disagreement about which nations should or should not be included in the category, when, and why. Certainly related conceptual terminology has changed over time in scope, meaning, and use. The term "western" draws on an affiliation with, or a perception of, a shared

It is difficult to determine which individuals or places or trends fit into which category, and the East–West contrast is sometimes criticized as relativistic and arbitrary.[49][50][51][page needed] Globalization has spread Western ideas so widely that almost all modern cultures are, to some extent, influenced by aspects of Western culture. Stereotypical views of "the West" have been labeled "Occidentalism", paralleling "Orientalism"—the term for the 19th-century stereotyped views of "the East".

Some

A former, now less-acceptable synonym for "Western civilisation" was "the white race".[54]

As Europeans discovered the extra-European world, old concepts adapted. The area that had formerly been considered the

History

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

The earliest civilizations which influenced the development of Western culture were those of Mesopotamia; the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran: the cradle of civilization.[56][57] Ancient Egypt similarly had a strong influence on Western culture.

Phoenician mercantilism and the introduction of the Alphabetic script boosted state formation in the Aegean and current-day Italy and current-day Spain, spawning civilizations in the Mediterranean such as Ancient Carthage, Ancient Greece, Etruria, and Ancient Rome.[58]

The

The West of the Mediterranean Region during the Antiquity

While the concept of a "West" did not exist until the emergence of the

Alexander's conquests led to the emergence of a

Following the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world, the concept of a "West" arose, as there was a cultural divide between the

For about five hundred years, the Roman Empire maintained the

From the time of Alexander the Great (the

The Greek and Roman

In a broader sense, the

The birth of European West during the Middle Ages

The Medieval West referred specifically to the Catholic "Latin" West, also called "Frankish" during Charlemagne's reign, in contrast to the Orthodox East, where Greek remained the language of the Byzantine Empire.

After the

Much of the basis of the post-Roman cultural world had been set before the fall of the Western Roman Empire, mainly through the integration and reshaping of Roman ideas through Christian thought. The

After the

Later Middle Ages (Rome and Reformation)

The rediscovery of the

In the 14th century, starting from Italy and then spreading throughout Europe,[75] there was a massive artistic, architectural, scientific and philosophical revival, as a result of the Christian revival of Greek philosophy, and the long Christian medieval tradition that established the use of reason as one of the most important of human activities.[76] This period is commonly referred to as the Renaissance. In the following century, this process was further enhanced by an exodus of Greek Christian priests and scholars to Italian cities such as Florence and Venice after the end of the Byzantine Empire with the fall of Constantinople.

From

Expansion of the West: the Era of Colonialism (15th–20th centuries)

Early modern era

From the late 15th century to the 17th century, Western culture began to spread to other parts of the world through explorers and missionaries during the Age of Discovery, and by imperialists from the 17th century to the early 20th century. During the Great Divergence, a term coined by Samuel Huntington[85] the Western world overcame pre-modern growth constraints and emerged during the 19th century as the most powerful and wealthy world civilization of the time, eclipsing Qing China, Mughal India, Tokugawa Japan, and the Ottoman Empire. The process was accompanied and reinforced by the Age of Discovery and continued into the modern period. Scholars have proposed a wide variety of theories to explain why the Great Divergence happened, including lack of government intervention, geography, colonialism, and customary traditions.

The Age of Discovery faded into the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th century, during which cultural and intellectual forces in European society emphasized reason, analysis, and individualism rather than traditional lines of authority. It challenged the authority of institutions that were deeply rooted in society, such as the Catholic Church; there was much talk of ways to reform society with toleration, science and skepticism.

Philosophers of the Enlightenment included Francis Bacon, René Descartes, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Voltaire (1694–1778), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant,[86] who influenced society by publishing widely read works. Upon learning about enlightened views, some rulers met with intellectuals and tried to apply their reforms, such as allowing for toleration, or accepting multiple religions, in what became known as enlightened absolutism. New ideas and beliefs spread around Europe and were fostered by an increase in literacy due to a departure from solely religious texts. Publications include Encyclopédie (1751–72) that was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert. The Dictionnaire philosophique (Philosophical Dictionary, 1764) and Letters on the English (1733) written by Voltaire spread the ideals of the Enlightenment.

Coinciding with the Age of Enlightenment was the

Industrial Revolution

The

The Industrial Revolution marks a major turning point in history; almost every aspect of daily life was influenced in some way. In particular, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. Some economists say that the major impact of the Industrial Revolution was that the standard of living for the general population began to increase consistently for the first time in history, although others have said that it did not begin to meaningfully improve until the late 19th and 20th centuries.[96][97][98] The precise start and end of the Industrial Revolution is still debated among historians, as is the pace of economic and social changes.[99][100][101][102] GDP per capita was broadly stable before the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy,[103] while the Industrial Revolution began an era of per-capita economic growth in capitalist economies.[104] Economic historians are in agreement that the onset of the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in the history of humanity since the domestication of animals, plants[105] and fire.

The First Industrial Revolution evolved into the Second Industrial Revolution in the transition years between 1840 and 1870, when technological and economic progress continued with the increasing adoption of steam transport (steam-powered railways, boats, and ships), the large-scale manufacture of machine tools and the increasing use of machinery in steam-powered factories.[106][107][108]

Post-Industrial era

Tendencies that have come to define modern Western societies include the concept of

In the 20th century, Christianity declined in influence in many Western countries, mostly in the European Union where some member states have experienced falling church attendance and membership in recent years,[111] and also elsewhere. Secularism (separating religion from politics and science) increased. Christianity remains the dominant religion in the Western world, where 70% are Christians.[112]

The West went through a series of great cultural and social changes between 1945 and 1980. The emergent mass media (film, radio, television and recorded music) created a global culture that could ignore national frontiers. Literacy became almost universal, encouraging the growth of books, magazines and newspapers. The influence of cinema and radio remained, while televisions became near essentials in every home.

By the mid-20th century, Western culture was exported worldwide, and the development and growth of international transport and telecommunication (such as

It was, in recent history, and remains, the dominant power and director of human civilization.[original research?]

Arts and humanities

While dance, music, visual art, story-telling, and architecture are human universals, they are expressed in the West in certain characteristic ways.[113]

In Western dance, music, plays and other arts, the performers are only very infrequently masked. There are essentially no taboos against depicting a god, or other religious figures, in a representational fashion.

Music

In music, Catholic monks developed the first forms of modern Western musical notation to standardize liturgy throughout the worldwide Church,[114] and an enormous body of religious music has been composed for it through the ages. This led directly to the emergence and development of European classical music and its many derivatives. The Baroque style, which encompassed music, art, and architecture, was particularly encouraged by the post-Reformation Catholic Church as such forms offered a means of religious expression that was stirring and emotional, intended to stimulate religious fervor.[115]

The

-

Claudio Monteverdi, 1567–1643

-

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi, 1678–1741

-

George Frideric Handel, 1685–1759

-

Johann Sebastian Bach, 1685–1750

-

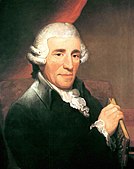

Franz Joseph Haydn, 1732–1809

-

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1756–1791

-

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1770–1827

-

Frédéric François Chopin, 1810–1849

-

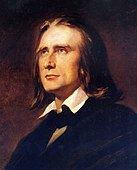

Franz Liszt, 1811–1886

Painting and photography

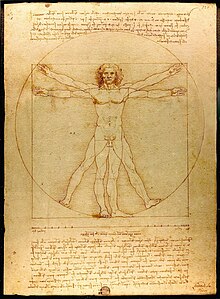

Jan van Eyck, among other renaissance painters, made great advances in oil painting, and perspective drawings and paintings had their earliest practitioners in Florence.[117] In art, the Celtic knot is a very distinctive Western repeated motif. Depictions of the nude human male and female in photography, painting, and sculpture are frequently considered to have special artistic merit. Realistic portraiture is especially valued.

Photography and the motion picture as both a technology and basis for entirely new art forms were also developed in the West.

-

Restoration of a fresco from an Ancient Roman villa bedroom, circa 50-40 BC, dimensions of the room: 265.4 × 334 × 583.9 cm, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Mona Lisa, by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1503 – 1506, perhaps continuing until circa 1517, oil on poplar panel, 77 cm × 53 cm, Louvre (Paris)

-

Dance at Le moulin de la Galette, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1876, oil on canvas, height: 131 cm, Musée d'Orsay (Paris)

-

Photo of the interior of the apartment of Eugène Atget, taken in 1910 in Paris

Dance and performing arts

The ballet is a distinctively Western form of performance dance.[118] The ballroom dance is an important Western variety of dance for the elite. The polka, the square dance, the flamenco, and the Irish step dance are very well known Western forms of folk dance.

The soap opera, a popular culture dramatic form, originated in the United States first on radio in the 1930s, then a couple of decades later on television. The music video was also developed in the West in the middle of the 20th century. Musical theatre was developed in the West in the 19th and 20th Centuries, from music hall, comic opera, and Vaudeville; with significant contributions from the Jewish diaspora, African-Americans, and other marginalized peoples.[119][120][121]

Literature

Western literature encompasses the literary traditions of Europe, as well as North America, Latin America and Oceania.[122]

While epic literary works in verse such as the

The novel, which made its appearance in the 18th century, is an essentially European creation. Chinese and Japanese literature contain some works that may be thought of as novels, but only the European novel is couched in terms of a personal analysis of personal dilemmas.[113]

As in its artistic tradition, European literature pays deep tribute to human suffering.[113] Tragedy, from its ritually and mythologically inspired Greek origins to modern forms where struggle and downfall are often rooted in psychological or social, rather than mythical, motives, is also widely considered a specifically European creation and can be seen as a forerunner of some aspects of both the novel and of classical opera.

The validity of reason was postulated in both Christian philosophy and the Greco-Roman classics.[113] Christianity laid a stress on the inward aspects of actions and on motives, notions that were foreign to the ancient world. This subjectivity, which grew out of the Christian belief that man could achieve a personal union with God, resisted all challenges and made itself the fulcrum on which all literary exposition turned, including the 20th–21st century novels.[113]

Architecture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

Important Western architectural motifs include the Doric, Corinthian, and Ionic orders of Greek architecture,[124] and the Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and Victorian styles, which are still widely recognized and used in contemporary Western architecture. Much of Western architecture emphasizes repetition of simple motifs, straight lines and expansive, undecorated planes. A modern ubiquitous architectural form that emphasizes this characteristic is the skyscraper, their modern equivalent first developed in New York and Chicago. The predecessor of the skyscraper can be found in the medieval towers erected in Bologna.

-

The facade of Angoulême Cathedral was built between 1110 and 1128 in the Romanesque style.

-

Stained glass windows of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, completed in 1248, mostly constructed between 1194 and 1220 in the Gothic style

-

The Palazzo Farnese, in Rome, built from 1534 to 1545, was designed by Sangallo and Michelangelo and is an important example of renaissance architecture.

-

The Palais Garnier in Paris, built between 1861 and 1875, a Beaux-Arts masterpiece

Cuisine

Western

Saracen influence can be seen in medieval cookbooks. Some recipes retain their Arabic names in Italian translations of the

Scientific and technological inventions and discoveries

A notable feature of Western culture is its strong emphasis and focus on innovation and invention through science and technology, and its ability to generate new processes, materials and material artifacts with its roots dating back to the Ancient Greeks. The scientific method as "a method or procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses" was fashioned by the 17th-century Italian Galileo Galilei,[127][128] with roots in the work of medieval scholars such as the 11th-century Iraqi physicist Ibn al-Haytham[129][130] and the 13th-century English friar Roger Bacon.[131]

By the

The West is credited with the development of the

Communication devices and systems including the

Ubiquitous materials including aluminum, clear glass,

The

In medicine, the pure

In mathematics,

The world's most widely adopted system of measurement, the International System of Units, derived from the metric system, was first developed in France and evolved through contributions from various Westerners.[170][171]

In business, economics, and finance,

Westerners are also known for their explorations of the globe and

Media

The roots of modern-day Western mass media can be traced back to the late 15th century, when

In the 16th century, a decrease in the preeminence of Latin in its literary use, along with the impact of economic change, the discoveries arising from trade and travel, navigation to the New World, science and arts and the development of increasingly rapid communications through print led to a rising corpus of vernacular media content in European society.[182]

After the launch of the satellite Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union in 1957, satellite transmission technology was dramatically realised, with the United States launching Telstar in 1962 linking live media broadcasts from the UK to the US. The first digital broadcast satellite (DBS) system began transmitting in US in 1975.[183]

Beginning in the 1990s, the Internet has contributed to a tremendous increase in the accessibility of Western media content. Departing from media offered in bundled content packages (magazines, CDs, television and radio slots), the Internet has primarily offered unbundled content items (articles, audio and video files).[184]

Religion

The native religions of Europe were

Western culture at some level is influenced by the

According to a survey by Pew Research Center from 2011, Christianity remains the dominant religion in the Western world where 70–84% are Christians,[112] According to this survey, 76% of Europeans described themselves as Christians,[112][190][191] and about 86% of the Americas' population identified themselves as Christians,[192] (90% in Latin America and 77% in North America).[193] 73% in Oceania self-identify as Christian, and 76% in South Africa are Christian.[112]

2012

At the same there has been an increase in the share of agnostic or

As in other areas, the Jewish diaspora and Judaism exist in the Western world.

There are also small but increasing numbers of people across the Western world who seek to revive the indigenous religions of their European ancestors; such

Sport

Since classical antiquity, sport has been an important facet of Western cultural expression.[203][204]

A wide range of sports was already established by the time of Ancient Greece and the military culture and the development of sports in Greece influenced one another considerably. Sports became such a prominent part of their culture that the Greeks created the Olympic Games, which in ancient times were held every four years in a small village in the Peloponnesus called Olympia. Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a Frenchman, instigated the modern revival of the Olympic movement. The first modern Olympic games were held at Athens in 1896.

The Romans built immense structures such as the

Jousting and hunting were popular sports in the European Middle Ages, and the aristocratic classes developed passions for leisure activities. A great number of popular global sports were first developed or codified in Europe. The modern game of golf originated in Scotland, where the first written record of golf is James II's banning of the game in 1457, as an unwelcome distraction to learning archery.[206]

The

Football (or soccer) remains hugely popular in Europe, but has grown from its origins to be known as the world game. Similarly, sports such as cricket, rugby, and netball were exported around the world, particularly among countries in the Commonwealth of Nations, thus India and Australia are among the strongest cricketing states, while victory in the Rugby World Cup has been shared among New Zealand, Australia, England, and South Africa.

Themes and traditions

Western culture has developed many themes and traditions, the most significant of which are:[citation needed]

- Greco-Roman classic letters, arts, architecture, philosophical and cultural tradition, which include the influence of preeminent authors and philosophers such as Cicero, as well as a long mythologic tradition.

- Christian ethical, philosophical, and mythological tradition, stemming largely from the Christian Bible, particularly the New Testament Gospels.[208][209][210]

- Monasteries, schools, libraries, books, book making, universities, teaching, education, and lecture halls.

- A tradition of the importance of the rule of law.

- freethinking and questioning of the church as an authority, which resulted in open-minded and reformist ideals inside, such as liberation theology, which partly adopted these currents, and secular and political tendencies such as separation of church and state (sometimes termed laicism), agnosticism and atheism.

- Generalized usage of some form of the Hieroglyphicsystems.

- presidentialism) and formal liberal democracyin recent times—prior to the 19th century, most Western governments were still monarchies.

- A large influence, in modern times, of many of the ideals and values developed and inherited from Romanticism.

- An emphasis on, and use of, science as a means of understanding the natural world and humanity's place in it.

- More pronounced use and application of innovation and scientific developments, as well as a more rational approach to scientific progress (what has been known as the scientific method).

See also

- Atlanticism

- Christendom

- Classical tradition

- Culture during the Cold War

- Eastern world

- Eastern culture

- European diaspora

- Greco-Roman world

- Western religion

- Westernization

- Western values

Notes

- ^ British archaeologist D.G. Hogarth published The Nearer East in 1902, which helped to define the term and its extent, including Albania, Montenegro, southern Serbia and Bulgaria, Greece, Egypt, all Ottoman lands, the entire Arabian Peninsula, and Western parts of Iran.

References

Citations

- ISBN 978-0-307-42518-8.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link - ISBN 978-0-534-64602-8.

- ISBN 978-90-04-13904-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link - ISBN 978-0-19-923743-2.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link - ISBN 978-0-19-157783-3.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link - ISBN 978-0-14-029323-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7425-6780-1.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link - ISBN 978-0-684-19303-8.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link - ISBN 978-1-111-83169-1.

- ISBN 978-1-305-63347-6.

- ^ Neill, Thomas Patrick (1957). Readings in the History of Western Civilization, Volume 2 (Newman Press ed.). p. 224.

- ISBN 978-0-19-925995-3.

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage (1956), Tübingen (Germany), pp. 317–319, 325–326

- ^ The Protestant Heritage Archived 23 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Britannica

- ISBN 978-0-226-56162-2.

- ISBN 978-0-8264-9482-5.

- ^ Roman Catholicism Archived 6 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, "Roman Catholicism, Christian church that has been the decisive spiritual force in the history of Western civilization". Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Caltron J.H Hayas, Christianity and Western Civilization (1953), Stanford University Press, p. 2: That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization—the civilization of western Europe and of America—have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo–Christianity, Catholic and Protestant.

- , accessed 8 December 2014. p. (preface)

- ISBN 978-1-111-83720-4.

- )

- ISBN 978-1-305-44548-2.

- OCLC 52605048.

- OCLC 851653645.

- ISSN 0733-4540.

- ^ a b Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- ISBN 3-540-20396-6.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7538-2413-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4411-1851-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-6747-6075-2

- ^ a b George Sarton: A Guide to the History of Science Waltham Mass. U.S.A. 1952

- ^ a b Burnett, Charles. "The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century", Science in Context, 14 (2001): 249–288.

- ^ OCLC 19353503.

- ^ "Western Civilization: Roots, History and Culture". TimeMaps. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. xix–xx

- ^ a b Verger 1999

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-505523-8.

- ^ a b Schumpeter, Joseph (1954). History of Economic Analysis. London: Allen & Unwin.

- ^ "Review of How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization by Thomas Woods, Jr". National Review Book Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-521-89057-1, pp. 189, 208

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 309.

- ISBN 8126913665.[page needed]

- ^ THE WORLD OF CIVILIZATIONS: POST-1990 scanned image Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-0-684-84441-1.)

The origin of western civilization is usually dated to 700 or 800 AD. In general, researchers consider that it has three main components, in Europe, North America and Latin America. [...] However, Latin America has followed a quite different development path from Europe and North America. Although it is a scion of European civilization, it also incorporates more elements of indigenous American civilizations compared to those of North America and Europe. It also currently has had a more corporatist and authoritarian culture. Both Europe and North America felt the effects of Reformation and combination of Catholic and Protestant cultures. Historically, Latin America has been only Catholic, although this may be changing. [...] Latin America could be considered, or a sub-set, within Western civilization, or can also be considered a separate civilization, intimately related to the West, but divided as to whether it belongs with it.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 978-1451628975.

- ^ Thomas Meaney, "The Return of 'The West'" New York Times March 11, 2022. Archived 22 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yin Cheong Cheng, New Paradigm for Re-engineering Education. p. 369

- Ainslie Thomas Embree, Carol Gluck, Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching. p. xvi

- ^ Kwang-Sae Lee, East and West: Fusion of Horizons[page needed]

- ^ a b c Kwame Anthony Appiah (9 November 2016). "There Is No Such Thing As Western Civilization".

- ^ Kwame Anthony Appiah (9 November 2016). "There Is No Such Thing As Western Civilization".

[...] the first recorded use of a word for Europeans as a kind of person, so far as I know, comes out of this history of conflict. In a Latin chronicle, written in 754 in Spain, the author refers to the victors of the Battle of Tours as Europenses, Europeans. So, simply put, the very idea of a 'European' was first used to contrast Christians and Muslims.

- ^

ISBN 9780374721107. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

[...] that one group of humans who used to refer to themselves as 'the white race' (and now, generally, call themselves by its more accepted synonym, 'Western cvilization') [...].

- S2CID 157454140.

- ISBN 0-563-17064-6

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey; A Very Short History of the World; Penguin Books, 2004

- ^ Scott 2018, pp. 38–39.

- ISBN 9781134374755.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-307-42518-8.

- ISBN 0-691-00659-8

- ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1

- ^ Hero (1899). "Pneumatika, Book ΙΙ, Chapter XI". Herons von Alexandria Druckwerke und Automatentheater (in Greek and German). Translated by Wilhelm Schmidt. Leipzig: B.G. Teubner. pp. 228–232.

- ^ Gordon, Cyrus H., The Common Background of the Greek and Hebrew Civilizations, W. W. Norton and Company, New York 1965

- OCLC 34892303.

- OCLC 9112202.

- ^ "How The Irish Saved Civilisation", by Thomas Cahill, 1995[page needed]

- ^ Kaiser, Wolfgang (2015). The Cambridge Companion to Roman Law. pp. 119–148.

- ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6.

- ISBN 978-90-04-22117-8.

- ^ "Valetudinaria". broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974869-3.

- ^ Chadwick, Owen p. 242.

- ^ de Torre, Fr. Joseph M. (1997). "A Philosophical and Historical Analysis of Modern Democracy, Equality, and Freedom Under the Influence of Christianity". Catholic Education Resource Center.

- ^ Burke, P., The European Renaissance: Centre and Peripheries (1998)

- ^ Grant God and Reason p. 9

- ^ ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Frank 2001.

- ^ Sootin, Harry. "Isaac Newton." New York, Messner (1955)

- ^ Galileo Galilei, Two New Sciences, trans. Stillman Drake, (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1974), pp. 217, 225, 296–97.

- JSTOR 2707514.

- ^ Marshall Clagett, The Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages, (Madison, Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1961), pp. 218–19, 252–55, 346, 409–16, 547, 576–78, 673–82; Anneliese Maier, "Galileo and the Scholastic Theory of Impetus", pp. 103–23 in On the Threshold of Exact Science: Selected Writings of Anneliese Maier on Late Medieval Natural Philosophy, (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Pr., 1982).

- ^ Hannam, p. 342

- ^ E. Grant, The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1996), pp. 29–30, 42–47.

- ^ "Scientific Revolution". Encarta. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- ^ Landes 1969, p. 40

- ^ Landes 1969

- ^ Watt steam engine File: located in the lobby of into the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the UPM (Madrid)

- ISBN 978-0-674-01601-9.

- S2CID 54816980.

- .

- ISBN 0-349-10484-0

- ]

- JSTOR 2598327.

- ^ Julie Lorenzen. "Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution". Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ^ Robert Lucas Jr. (2003). "The Industrial Revolution". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

it is fairly clear that up to 1800 or maybe 1750, no society had experienced sustained growth in per capita income. (Eighteenth century population growth also averaged one-third of 1 percent, the same as production growth.) That is, up to about two centuries ago, per capita incomes in all societies were stagnated at around $400 to $800 per year.

- ^ Lucas, Robert (2003). "The Industrial Revolution Past and Future". Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

[consider] annual growth rates of 2.4 percent for the first 60 years of the 20th century, of 1 percent for the entire 19th century, of one-third of 1 percent for the 18th century

- ^ McCloskey, Deidre (2004). "Review of The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain (edited by Roderick Floud and Paul Johnson), Times Higher Education Supplement, 15 January 2004".

- ISBN 978-0-87332-101-3. No name is given to the transition years. The "Transportation Revolution" began with improved roads in the late 18th century.

- ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

- ^ Hunter 1985

- Science Daily.

- ^ "A brief history of Western culture". Khan Academy.

- ^ Ford, Peter (22 February 2005). "What place for God in Europe". USA Today. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d ANALYSIS (19 December 2011). "Global Christianity". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Deak, Istvan (1996). Encyclopedia Americana. p. 688.

- ^ Hall, p. 100.

- ^ Murray, p. 45.

- ISBN 978-0-486-45265-4

- ^ Barzun, p. 73

- ^ Barzun, p. 329

- OCLC 668182929.

- OCLC 52520631.

- OCLC 654535012.

- ^ "Western literature". 9 May 2023.

- ^ Barzun, p. 380

- ^ "Western architecture". britannica.com. Britannica. 22 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b Wilson, Anne (2002). The Saracen Connection: Arab Cuisine and the Medieval West.

- ^ Graduation through the ages http://www.canterbury.ac.nz/graduation/grad-history.shtml Archived 25 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "scientific method", Oxford Dictionaries: British and World English, 2016, archived from the original on 20 June 2016, retrieved 28 May 2016

- ISBN 0-486-24823-2

- ^ Jim Al-Khalili (4 January 2009). "The 'first true scientist'". BBC News.

- ISBN 978-0-393-70607-9.

Alhazen (or Al-Haytham; 965–1039 CE) was perhaps one of the greatest physicists of all times and a product of the Islamic Golden Age or Islamic Renaissance (7th–13th centuries). He made significant contributions to anatomy, astronomy, engineering, mathematics, medicine, ophthalmology, philosophy, physics, psychology, and visual perception and is primarily attributed as the inventor of the scientific method, for which author Bradley Steffens (2006) describes him as the "first scientist".

- S2CID 195048595.

- ^ "Which country has the best brains?". BBC News. 8 October 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950, Paperback – 9 November 2004, p. 284

- ISBN 978-0-387-98744-6.

- doi:10.1038/053516a0.

- ^ Tom McInally, The Sixth Scottish University. The Scots Colleges Abroad: 1575 to 1799 (Brill, Leiden, 2012) p. 115

- S2CID 51658522.

- ISBN 978-0-14-312444-3.

- ^ Ralph Stein (1967). The Automobile Book. Paul Hamlyn Ltd

- ^ Diesel's Rational Heat Motor by Rudolph Diesel

- ^ Fermi, Enrico (December 1982). The First Reactor. Oak Ridge, Tennessee: United States Atomic Energy Commission, Division of Technical Information. pp. 22–26.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-2609-6.

- ^ "U.S. Supreme Court". Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Contents". brophy.net. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Who invented the cell phone?". brophy.net. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "IPTO – Information Processing Techniques Office" Archived 2 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Living Internet, Bill Stewart (ed), January 2000.

- ISBN 978-0-309-05283-2. Retrieved 16 August 2013., https://books.google.com/books?id=FAHk65slfY4C&pg=PA16

- ^ "Arthur C. Clarke Extra Terrestrial Relays". Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Philo Taylor Farnsworth (1906–1971)" Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Collingridge, M. R. et al. (2007) "Ink Reservoir Writing Instruments 1905–20" Transactions of the Newcomen Society 77(1): pp. 69–100, p. 69

- ISBN 978-0-470-51234-0.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-486-25128-8.

- ISBN 978-0-520-23802-2.

electrophorus volta.

- .

- ^ "A Poor Substitute". www.pslc.ws. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-521-65474-6.

- ^ "This Is Cheshire - Winnington history in the making". 21 January 2010. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-941901-03-1.

- ^ Liebig, Justus Freiherr von (1872). Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German). C.F. Winter'sche.

- ^ Liebig, Justus. "Justus Liebig's Annalen der Chemie. v.31-32 1839". Annalen der Chemie. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Annales de chimie et de physique. Ser.2 v.67 1838". HathiTrust. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ *Elwes, Richard, "An enormous theorem: the classification of finite simple groups", Plus Magazine, Issue 41, December 2006. Archived 2 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Richard Swineshead (1498), Calculationes Suiseth Anglici, Papie: Per Franciscum Gyrardengum.

- ISBN 0-19-920613-9

- ISBN 978-0-521-66160-7

- ISBN 978-0-19-521942-5.

- ISBN 978-0-19-506137-6.

- ISBN 978-0-03-029804-2.

- ^ "Metrication in other countries". USMA. US Metric Association. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ISSN 0772-7674. Archived from the original(PDF) on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ (Chapters 9, 10, 11, 13, 25 and 26) and three times (Chapters 4, 8 and 19) in its sequel, Equality

- ^ Humble, Richard (1978). The Seafarers – The Explorers. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books.

- )

- ^ Nelson, Jon. "Mars Exploration Rover – Spirit". NASA. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Nelson, Jon. "Mars Exploration Rover -Opportunity". NASA. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Applied Physics Lab.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie; Buckley, Mike; Stotoff, Maria (14 July 2015). "15-149 NASA's Three-Billion-Mile Journey to Pluto Reaches Historic Encounter". NASA. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ Butrica, Andrew. From Engineering Science to Big Science. p. 267. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- .:

At the same time, then as the printing press in the physical technological sense was invented, 'the press' in the extended sense of the word also entered the historical stage. The phenomenon of publishing was now born.

- ISBN 978-1-135-25370-7.

- ISBN 978-1-135-25370-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4462-4566-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-111-83169-1.

- ISBN 9781139484138.

..for the Jews in twentieth-century Europe, the cradle of Christian civilization.

- ISBN 9781108486095.

..for the Jews in twentieth-century Europe, the cradle of Christian civilization.

- ISBN 9780141954714.

Europe is historically the cradle of Christian culture, it is still the primary center of institutional and pastoral energy in the Catholic Church...

- ISBN 9781317606307.

Europe is historically the cradle of Christian culture, it is still the primary center of institutional and pastoral energy in the Catholic Church...

- ^ "Europe". Pewforum.org. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Christians". Pewforum.org. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ ANALYSIS (19 December 2011). "Americas". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ ANALYSIS (19 December 2011). "Global religious landscape: Christians". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Discrimination in the EU in 2012" (PDF), Special Eurobarometer, 393, European Union: European Commission, p. 233, 2012, retrieved 14 August 2013 The question asked was "Do you consider yourself to be...?" With a card showing: Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Other Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu, Atheist, and Non-believer/Agnostic. Space was given for Other (SPONTANEOUS) and DK. Jewish, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu did not reach the 1% threshold.

- ^ "Discrimination in the EU in 2012" (PDF). Special Eurobarometer. 383: 233. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ ISBN 9789004346307.

- ISBN 9781443891592.

- ^ "Religiously Unaffiliated". Pewforum.org. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Germany". State.gov. 14 September 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Views on globalisation and faith Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ipsos MORI, 5 July 2011.

- ^ (in French) Catholicisme et protestantisme en France: Analyses sociologiques et données de l'Institut CSA pour La Croix Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine – Groupe CSA TMO for La Croix, 2001

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2007". 14 September 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ William Joseph Baker, Sports in the western world (University of Illinois Press, 1988).

- ^ David G. McComb, Sports in world history (Routledge, 2004).

- ^ Barbara Schrodt, "Sports of the Byzantine empire." Journal of Sport History 8.3 (1981): 40-59.

- ^ Sall E. D. Wilkins, Sports and games of medieval cultures (Greenwood, 2002).

- ^ Tranter, N. L. "Popular sports and the industrial revolution in Scotland: the evidence of the statistical accounts." International Journal of the History of Sport 4.1 (1987): 21-38.

- ISBN 9780521889520.

The Bible is the most globally influential and widely read book ever written. ... it has been a major influence on the behavior, laws, customs, education, art, literature, and morality of Western civilization.

- ISBN 9780199759217.

- ISBN 9780809128501.

Sources

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Global communication without universal civilization. INU societal research. Vol. 1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 978-2-88155-004-1.

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Coexisting Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. INUPRESS, Geneva, 119–244. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Atle Hesmyr (2013). Civilization, Oikos, and Progress ISBN 978-1468924190

- Barzun, Jacques ISBN 0-06-017586-9.

- Daly, Jonathan. "The Rise of Western Power: A Comparative History of Western Civilization Archived 30 June 2017 at the ISBN 978-1441161314.

- Daly, Jonathan. "Historians Debate the Rise of the West" (London and New York: Routledge, 2015). ISBN 978-1138774810.

- Derry, T. K. and Williams, Trevor I. A Short History of Technology: From the Earliest Times to A.D. 1900 Dover (1960) ISBN 0-486-27472-1.

- Duran, Eduardo, Bonnie Dyran Native American Postcolonial Psychology 1995 Albany: State University of New York Press ISBN 0-7914-2353-0

- Hanson, Victor Davis; Heath, John (2001). Who Killed Homer: The Demise of Classical Education and the Recovery of Greek Wisdom, Encounter Books.

- Jones, Prudence and Pennick, Nigel A History of Pagan Europe Barnes & Noble (1995) ISBN 0-7607-1210-7.

- Meaney, Thomas "The Return of 'The West'" New York Times March 11, 2022.

- Merriman, John Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present W. W. Norton (1996) ISBN 0-393-96885-5.

- McClellan, James E. III and Dorn, Harold Science and Technology in World History Johns Hopkins University Press (1999) ISBN 0-8018-5869-0.

- Stein, Ralph The Great Inventions Playboy Press (1976) ISBN 0-87223-444-4.

- Asimov, Isaac Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology: The Lives & Achievements of 1510 Great Scientists from Ancient Times to the Present Revised second edition, Doubleday (1982) ISBN 0-385-17771-2.

- Secret Archives of the Vaticanand other original sources, 40 vols. St. Louis, B. Herder (1898ff.)

- Stearns, P.N. (2003). Western Civilization in World History, Routledge, New York.

- Thornton, Bruce (2002). Greek Ways: How the Greeks Created Western Civilization, Encounter Books.

- ISBN 978-1-101-54802-8

- ISBN 978-0-525-42757-5

- ISBN 978-0374173227

- ISBN 978-0812972337

- ISBN 978-1497603257

- Headley, John M. The Europeanization of the World: On the Origins of Human Rights and Democracy, ISBN 9780691171487

Further reading

- Barzun, Jacques. From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life : 1500 to the Present. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

- Hesmyr, Atle Kultorp: Civilization; Its Economic Basis, Historical Lessons and Future Prospects (Telemark: Nisus Publications, 2020).

External links

- An overview of the Western Civilization Archived 24 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine