Western gull

| Western gull | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult | |

| |

| Juvenile (1st Winter) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Larus |

| Species: | L. occidentalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Larus occidentalis Audubon, 1839

| |

| |

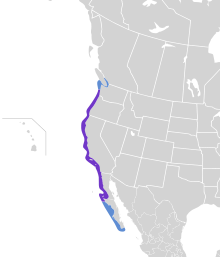

| Distribution Year-round Nonbreeding

| |

The western gull (Larus occidentalis) is a large white-headed

It was previously considered

Physical description

The western gull is a large gull that can measure 55 to 68 cm (22 to 27 in) in total length, spans 130 to 144 cm (51 to 57 in) across the wings, and weighs 800 to 1,400 g (1.8 to 3.1 lb).

Two subspecies are recognized, differentiated by the mantle and eye colouration.[9] The northern subspecies L. o. occidentalis is found between Central Washington and Central California, has dark grey upperparts. The southern subspecies L. o. wymani is found between central and southern California has a darker mantle (approaching that of the Great black-backed gull) and has paler eyes on average. wymani has more advanced plumage development than occidentalis, and generally attains adult plumage by the third year.[3]

Auditory description

The call of the Western gull is bright, piercing, and repetitive.

Distribution and habitat

The western gull is a year-round resident in California, Oregon, Baja California, and southern Washington. It is migratory, moving to northern Washington, British Columbia, and Baja California Sur to spend the nonbreeding season.

Behavior

The western gull rarely ventures more than approximately 100 miles inland, almost never very far from the ocean;

Feeding

Western gulls feed in

Reproduction

A nest of vegetation is constructed inside the parent's territory and 3 eggs are laid. These eggs are incubated for a month. The chicks, once hatched, remain inside the territory until they have fledged. Chicks straying into the territory of another gull are liable to be killed by that territory's pair. Chick mortality is high, with on average one chick surviving to fledging. On occasion, abandoned chicks will be adopted by other gulls.

Hybridization

Between Puget Sound in Washington and Northern Oregon, the western gull hybridizes frequently with the glaucous-winged gull, a cross referred to as the Olympic gull.[9] Hybrids between the two species are variable and may features of either parent species, they have paler mantles and wingtips paler than Western gulls but darker than Glaucous-winged gulls. Additionally, the nonbreeding plumage of hybrids typically has darker head markings than pure Western gulls, which have little to no streaking in their nonbreeding plumage.[3]

The prevalence of 'Olympic gull' hybrids is an example of bounded hybrid superiority, where natural selection favours hybrids in areas of intermediate habitat. One study found that females paired with hybrid males have higher breeding success than pairs of the same species.[11] In the central part of the hybrid zone, clutch size was larger among pairs with hybrid males, many of which established breeding grounds in more vegetative cover than pure western gull males, which preferred sand habitat resulting in heavier predation. In the northern section of the hybrid zone, there was no difference in clutch size, but breeding success is higher due to the hybrids being more similar to western gulls in foraging behaviour, feeding more on fish than glaucous-winged gulls. Little evidence of assortative mating was observed, except for weak assortative mating among hybrids in absence of mixed species pairs.

Western gulls and humans

The western gull is currently not considered threatened. However, they have, for a gull, a restricted range. Numbers were greatly reduced in the 19th century by the taking of seabird eggs for the growing city of San Francisco. Western gull colonies also suffered from disturbance where they were turned into lighthouse stations, or, in the case of Alcatraz, a prison.

Western gulls are very aggressive when defending their territories and consequently were persecuted by some as a menace. The automation of lighthouses and the closing of Alcatraz Prison allowed the species to reclaim parts of its range. They are currently vulnerable to climatic events like

Thousands of western gulls and chicks reside at the Anacapa Island in Channel Islands National Park.

Western gulls have become a serious nuisance to the

In media

The western gull was one of the antagonists in Alfred Hitchcock's famous movie The Birds which was filmed in Bodega Bay, California.

Gallery

-

A western gull chick on Alcatraz Island

-

3-week-old chick

-

Portrait

-

Feeding on a starfish

-

Vocalizing

-

Adults fighting

-

A pair at Point Lobos

References

- . Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Western Gull". U.S. National Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-0691119977.

- ISBN 978-0-395-60291-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ a b "Western Gull". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ JSTOR 4523362.

- ^ a b Rogers, Paul (20 July 2013). "AT&T Park gulls vex San Francisco Giants". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ OCLC 1005861102.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - .

- PMID 11108604.

Additional sources

- Pierotti, R.J.; Annett, C.A. (1995). "Western Gull (Larus occidentalis)". In Poole, A.; Gill, F. (eds.). The Birds of North America. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

External links

- Western Gull Facts - from University of Washington Nature Mapping Program

- Oregon Coast Today - Seagull article

- "Western gull media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Western gull photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Western gull at IUCN Red List maps