Wildcat

| Wildcat | |

|---|---|

| |

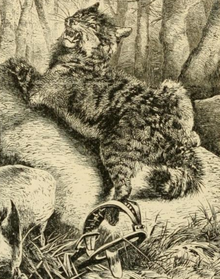

| European wildcat (Felis silvestris) | |

| |

| African wildcat (Felis lybica) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Felis |

| Binomial name | |

| Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777 | |

| Felis lybica Forster, 1780 | |

![Distribution of the wildcat species complex[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Wild_Cat_Felis_silvestris_distribution_map.png/220px-Wild_Cat_Felis_silvestris_distribution_map.png)

| |

| Distribution of the wildcat species complex[1] | |

The wildcat is a

The wildcat and the other members of the

The wildcat is categorized as

The association of African wildcats and humans appears to have developed along with the establishment of settlements during the

Taxonomy

Felis (catus) silvestris was the

In subsequent decades, several naturalists and explorers described 40 wildcat specimens collected in European, African and Asian range countries. In the 1940s, the taxonomist Reginald Innes Pocock reviewed the collection of wildcat skins and skulls in the Natural History Museum, London, and designated seven F. silvestris subspecies from Europe to Asia Minor, and 25 F. lybica subspecies from Africa, and West to Central Asia. Pocock differentiated the:[13][14]

- Forest wildcat subspecies (silvestris group)

- Steppe wildcat subspecies (ornata-caudata group): is distinguished from the forest wildcat by being smaller, with comparatively lighter fur colour, and longer and more sharply-pointed tails.[14] The domestic cat is thought to have derived from this group.[15][7][6]

- Bush wildcat subspecies (ornata-lybica group): is distinguished from the steppe wildcat by paler fur, well-developed spot patterns and bands.[14]

In 2005, 22 subspecies were recognized by the authors of Mammal Species of the World, who allocated subspecies largely in line with Pocock's assessment.[16]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force revised the taxonomy of the Felidae, and recognized the following as valid taxa:[2]

| Species and subspecies | Characteristics | Image |

|---|---|---|

| European wildcat (F. silvestris) Schreber, 1777; syn. F. s. ferus Erxleben, 1777; obscura Desmarest, 1820; hybrida Fischer, 1829; ferox Martorelli, 1896; morea Trouessart, 1904; grampia Miller, 1907; tartessia Miller, 1907; molisana Altobello, 1921; reyi Lavauden, 1929; jordansi Schwarz, 1930; euxina Pocock, 1943; cretensis Haltenorth, 1953 | This species and the |  |

| Caucasian wildcat (F. s. caucasica) Satunin, 1905; syn. trapezia Blackler, 1916 | This subspecies is light grey with well developed patterns on the head and back and faint transverse bands and spots on the sides. The tail has three distinct black transverse rings.[17] | |

| African wildcat (F. lybica) Forster, 1780; syn. F. l. ocreata Gmelin, 1791; nubiensis Kerr, 1792; maniculata Temminck, 1824; mellandi Schwann, 1904; rubida Schwann, 1904; ugandae Schwann, 1904; mauritana Cabrera, 1906; nandae Heller, 1913; taitae Heller, 1913; nesterovi Birula, 1916; iraki Cheesman, 1921; hausa Thomas and Hinton, 1921; griselda Thomas, 1926; brockmani Pocock, 1944; foxi Pocock, 1944; pyrrhus Pocock, 1944; gordoni Harrison, 1968 | This species and the nominate subspecies has pale, buffish or light-greyish fur with a tinge of red on the dorsal band; the length of its pointed tail is about two-thirds of the head to body size.[18] |  |

| Southern African wildcat (F. l. cafra) Desmarest, 1822; syn. F. l. xanthella Thomas, 1926; small | This subspecies does not differ significantly in colour and pattern from the nominate one. The available zoological specimens merely have slightly longer skulls than those from farther north in Africa.[14] |  |

| Asiatic wildcat (F. l. ornata) Gray, 1830; syn. syriaca Tristram, 1867; caudata Gray, 1874; maniculata Yerbury and Thomas, 1895; kozlovi Satunin, 1905; matschiei Zukowsky, 1914; griseoflava Zukowsky, 1915; longipilis Zukowsky, 1915; macrothrix Zukowsky, 1915; murgabensis Zukowsky, 1915; schnitnikovi Birula, 1915; issikulensis Ognev, 1930; tristrami Pocock, 1944 | This subspecies has dark spots on light, ochreous-grey coloured fur.[14] |  |

Evolution

The wildcat is a member of the Felidae, a family that had a

The European wildcat's direct ancestor was Felis lunensis, which lived in Europe in the late Pliocene and Villafranchian periods. Fossil remains indicate that the transition from lunensis to silvestris was completed by the Holstein interglacial about 340,000 to 325,000 years ago.[5]

Craniological differences between the European and African wildcats indicate that the wildcat probably migrated during the Late Pleistocene from Europe into the Middle East, giving rise to the steppe wildcat phenotype.[3]

Characteristics

The wildcat has pointed ears, which are moderate in length and broad at the base.[13][14] Its whiskers are white, number 7 to 16 on each side and reach 5–8 cm (2.0–3.1 in) in length on the muzzle. Whiskers are also present on the inner surface of the paw and measure 3–4 cm (1.2–1.6 in). Its eyes are large, with vertical

The European wildcat has a greater skull volume than the domestic cat, a ratio known as Schauenberg's index.[21] Further, its skull is more spherical in shape than that of the jungle cat (F. chaus) and leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis). Its dentition is relatively smaller and weaker than the jungle cat's.[22]

Both wildcat species are larger than the domestic cat.[13][14] The European wildcat has relatively longer legs and a more robust build compared to the domestic cat.[23] The tail is long, and usually slightly exceeds one-half of the animal's body length. The species size varies according to Bergmann's rule, with the largest specimens occurring in cool, northern areas of Europe and Asia such as Mongolia, Manchuria and Siberia.[24] Males measure 43–91 cm (17–36 in) in head to body length, 23–40 cm (9.1–15.7 in) in tail length, and normally weigh 5–8 kg (11–18 lb). Females are slightly smaller, measuring 40–77 cm (16–30 in) in body length and 18–35 cm (7.1–13.8 in) in tail length, and weighing 3–5 kg (6.6–11.0 lb).[22]

Both sexes have two

Distribution and habitat

The European wildcat inhabits

The African wildcat lives in a wide range of habitats except

Behaviour and ecology

Both wildcat species are largely

When threatened, it retreats into a burrow, rather than climb trees. When taking residence in a tree hollow, it selects one low to the ground. Dens in rocks or burrows are lined with dry grasses and bird feathers. Dens in tree hollows usually contain enough sawdust to make lining unnecessary. If the den becomes infested with fleas, the wildcat shifts to another den. During winter, when snowfall prevents the European wildcat from travelling long distances, it remains within its den until travel conditions improve.[30]

Territorial marking consists of

Hunting and prey

The European wildcat primarily preys on small mammals such as European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) and rodents.[33] It also preys on

The African wildcat preys foremost on murids, to a lesser extent also on birds, small reptiles and invertebrates.[37]

Reproduction and development

The wildcat has two

Kittens are born with closed eyes and are covered in a fuzzy coat.

Generation length of the wildcat is about eight years.[41]

Predators and competitors

Because of its habit of living in areas with rocks and tall trees for refuge, dense thickets and abandoned burrows, wildcats have few natural predators. In Central Europe, many kittens are killed by

Threats

Wildcat populations are foremost threatened by hybridization with the domestic cat. Mortality due to traffic accidents is a threat especially in Europe.

In the

Conservation

Wildcat species are protected in most range countries and listed in

In culture

Domestication

An African wildcat skeleton

In mythology

Celtic fables of the

In heraldry

The

In literature

- The patch is kind enough ; but a huge feeder

- Snail-slow in profit, and he sleeps by day

- More than the wild cat.

— The Merchant of Venice Act 2 Scene 5 lines 47–49

- Thou must be married to no man but me ;

- For I am he, am born to tame you, Kate ;

- And bring you from a wild cat to a Kate

- Comfortable, as other household Kates.

— The Taming of the Shrew Act 2 Scene 1 lines 265–268

- Thrice the brinded cat hath mew'd.

— Macbeth Act 4 Scene 1 line 1

References

- ^ . Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ a b Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 16−20.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 40185850.

- ^ a b Kurtén, B. (1965). "On the evolution of the European Wild Cat, Felis silvestris Schreber" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Fennica. 111: 3–34.

- ^ PMID 17600185.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-63495-3.

- ^ a b Baldwin, J. A. (1975). "Notes and speculations on the domestication of the cat in Egypt". Anthropos. 70 (3/4): 428−448.

- ^ a b c Kilshaw 2011, pp. 2–3

- ^ a b c Hamilton 1896, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b Schreber, J. C. D. (1778). "Die wilde Kaze". Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen (Dritter Theil) [The mammals with illustrations and descriptions (Part 3)]. Erlangen: Expedition des Schreber'schen Säugthier- und des Esper'schen Schmetterlingswerkes. pp. 397–402.

- ^ Forster, G. (1780). "LIII. Der Karakal". Herrn von Buffon's Naturgeschichte der vierfüssigen Thiere. Mit Vermehrungen, aus dem Französischen übersetzt [M. de Buffon's Natural History of Quadrupeds. With additions, translated from French]. Vol. 6. Berlin: J. Pauli. pp. 304–307.

- ^ a b c d Pocock, R. I. (1951). "Felis silvestris, Schreber". Catalogue of the Genus Felis. London: Trustees of the British Museum. pp. 29−50.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pocock, R. I. (1951). "Felis lybica, Forster". Catalogue of the Genus Felis. London: Trustees of the British Museum. pp. 50−133.

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 452–455

- OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Satunin, K. A. (1905). "Die Säugetiere des Talyschgebietes und der Mughansteppe" [The Mammals of the Talysh area and the Mughan steppe]. Mitteilungen des Kaukasischen Museums (2): 87–402.

- ^ ISBN 978-0565007232.

- S2CID 41672825.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 402–403

- ^ Schauenberg, P. (1969). "L'identification du Chat forestier d'Europe Felis s. silvestris Schreber, 1777 par une méthode ostéométrique". Revue Suisse de Zoologie. 76: 433−441.

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 408–409

- ^ Schauenberg, P. (1969). "L'identification du Chat forestier d'Europe Felis s. silvestris Schreber, 1777 par une méthode ostéométrique". Revue Suisse de Zoologie. 76: 433−441.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 452

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 405–407

- hdl:10447/600656.

- ^ Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "African Wildcat Felis silvestris, lybica group (Forster, 1770)". Wild Cats: status survey and conservation action plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 32−35. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- ISBN 978-0-8008-8324-9.

- ISBN 0-226-77999-8.

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 433–434

- ^ Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 403

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 432

- S2CID 3096866. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2019-02-19.

- ^ a b c Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 429–431

- ^ Tomkies 2008, pp. 50

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 480

- hdl:2263/16378.

- ^ a b c d e Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 434–437

- ^ a b c d Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 404

- ISBN 978-0521341783.

- ^ Pacifici, M.; Santini, L.; Di Marco, M.; Baisero, D.; Francucci, L.; Grottolo Marasini, G.; Visconti, P.; Rondinini, C. (2013). "Generation length for mammals". Nature Conservation (5): 87–94.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 438

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 491–493

- ^ Hunter, Luke. Field guide to carnivores of the world. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

- ISBN 9781408134559.

- ^ Kingdon 1988, pp. 316

- ^ Hatfield, Richard Stratton. "Diet and space use of the martial eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus) in the Maasai Mara region of Kenya." (2018).

- ]

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 440–441 & 496–498

- ^ Bachrach, M. (1953). "Cat family − Lynx Cat and Wild Cat". Fur, a practical treatise (Third ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall Incorporated. pp. 188–189.

- ^ Vogel, B.; Mölich, T.; Klar, N. (2009). "Der Wildkatzenwegeplan – Ein strategisches Instrument des Naturschutzes" [The Wildcat Infrastructure Plan – a strategic instrument of nature conservation] (PDF). Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung. 41 (11): 333–340. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-29. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- ^ Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Group (2013). Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan. Edinburgh: Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- S2CID 28294367.

- ^ Vinycomb, J. (1906). "Cat-a-Mountain − Tiger Cat or Wild Cat". Fictitious & symbolic creatures in art, with special reference to their use in British heraldry. London: Chapman and Hall Limited. pp. 205−208.

Sources

- Hamilton, E. (1896). The wild cat of Europe (Felis catus). London: R. H. Porter.

- Harris, S.; Yalden, D. W. (2008). Mammals of the British Isles (4th Revised ed.). Southampton: Mammal Society. ISBN 978-0906282656.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Wildcat". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 398–498.

- Kilshaw, K. (2011). Scottish Wildcats: Naturally Scottish (PDF). Perth, Scotland: Scottish Natural Heritage. ISBN 9781853976834. Archived from the original(PDF) on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- Kingdon, J. (1988). East African mammals: an atlas of evolution in Africa. Volume 3, Part 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226437217.

- Tomkies, M. (2008). Wildcat Haven. Dunbeath: Whittles Publishing. ISBN 9781849953122.

Further reading

- Kurtén, B. (1968). Pleistocene mammals of Europe. New Brunswick and London: Aldine Transaction. ISBN 9781412845144.

- Osborn, D. J.; Helmy, I. (1980). "Felis sylvestris Schreber, 1777". The contemporary land mammals of Egypt (including Sinai). Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. pp. 440−444.

External links

- "European Wildcat". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "African Wildcat". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "Asiatic Wildcat". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777". UNEP Global Resource Information Database.

- "Wildcat (Felis silvestris) images". ARKive. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- "Felis silvestris (Schreber)". Envis Centre of Faunal diversity. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-09-20.

- "Felis silvestris lybica, African Wildcat: 3D computed tomographic (CT) animations of male and female African wildcat skulls". Digimorph.org.

- Scottish wildcat

- "Information and education website on the Scottish wildcat and conservation efforts". Save the Scottish Wildcat. Archived from the original on 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- "Conserving the Scottish wildcat in the West Highlands". Wildcat Haven. Archived from the original on 2015-08-21. Retrieved 2010-09-20.