Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick | |

|---|---|

without Portfolio | |

| In office 24 August 1943 – 30 April 1945 | |

| Additional positions | |

| 1939–1945 | Member of the Council of Ministers for the Defense of the Reich |

| 1934—1945 | Member of the Prussian State Council |

| 1933—1945 | Reichsleiter |

| 1933–1945 | Member of the Reichstag (Nazi Germany) |

| 1924—1933 | Member of the Reichstag (Weimar Republic) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 March 1877 Execution by hanging |

| Political party | Nazi Party |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5 |

War crimes Crimes against humanity | |

| Trial | Nuremberg trials |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

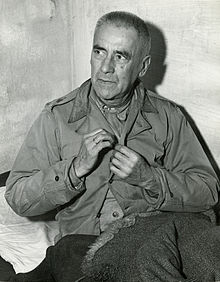

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a convicted war criminal and prominent German politician of the

As the head of the

After World War II, Frick was tried and convicted of

.Early life

Born in the Palatinate municipality of Alsenz, then part of the Kingdom of Bavaria, Germany, the last of four children of Protestant teacher Wilhelm Frick sen. (d. 1918) and his wife Henriette (née Schmidt). He attended the gymnasium in Kaiserslautern, passing his Abitur exams in 1896. He went on studying philology at the University of Munich, but soon after turned to study law at Heidelberg and Humboldt University of Berlin. He received his doctorate of law in 1901. He joined the Bavarian civil service in 1903, working as an attorney at the Munich Police Department. He was appointed a Bezirksamtassessor in Pirmasens in 1907 and became acting district executive in 1914. Rejected as unfit, Frick did not serve in World War I. He was promoted to the official rank of a Regierungsassessor and, at his own request, re-assumed his post at the Munich Police Department in 1917.[6]

On 25 April 1910, Frick married Elisabetha Emilie Nagel (1890–1978) in Pirmasens. They had two sons and a daughter. The marriage ended in an ugly divorce in 1934. A few weeks later, on 12 March, Frick remarried in Münchberg Margarete Schultze-Naumburg (1896–1960), the former wife of the Nazi Reichstag MP Paul Schultze-Naumburg. Margarete gave birth to a son and a daughter.

Nazi career

In Munich, Frick witnessed the end of the war and the German Revolution of 1918–1919. He sympathized with right-wing Freikorps paramilitary units. Chief of Police Ernst Pöhner introduced him to Adolf Hitler, whom he helped willingly with obtaining permission to hold political rallies and demonstrations.

Elevated to the rank of an Oberamtmann and head of the Political department of the Munich police from 1923, he and Pöhner participated in Hitler's failed

In the aftermath of the putsch, Wilhelm Frick was elected a member of the German

In 1929, as the price for joining the coalition government of the Land (state) of Thuringia, the NSDAP received the state ministries of the Interior and Education. On 23 January 1930, Frick was appointed to these ministries, becoming the first Nazi to hold a ministerial-level post at any level in Germany (though he remained a member of the Reichstag).[8] Frick used his position to dismiss Communist and Social Democratic officials and replace them with Nazi Party members, so Thuringia's federal subsidies were temporarily suspended by Reich Minister Carl Severing. Frick also appointed the eugenicist Hans F. K. Günther as a professor of social anthropology at the University of Jena, banned several newspapers, and banned pacifist drama and anti-war films such as All Quiet on the Western Front. He was removed from office by a Social Democratic motion of no confidence in the Thuringian Landtag parliament on 1 April 1931.

Reich Minister

When Reich president

Frick's power dramatically increased as a result of the

, where Hitler reserved the right to appoint the mayors himself if he deemed it necessary). He also had considerable influence over smaller towns as well; while their mayors were appointed by the state governors, as mentioned earlier the governors were responsible to him.

Frick was instrumental in the

In the summer of 1938 Frick was named the patron (Schirmherr) of the

From the mid-to-late 1930s Frick lost favour irreversibly within the Nazi Party after a power struggle involving attempts to resolve the lack of coordination within the Reich government.

Frick's replacement as Reichsminister of the Interior did not reduce the growing administrative chaos and infighting between party and state agencies.

Trial and execution

Frick was arrested, and was arraigned at the

Frick was sentenced to death on 1 October 1946, and was hanged at Nuremberg Prison on 16 October. Of his execution, journalist Joseph Kingsbury-Smith wrote:

The sixth man to leave his prison cell and walk with handcuffed wrists to the death house was 69-year-old Wilhelm Frick. He entered the execution chamber at 2.05 am, six minutes after Rosenberg had been pronounced dead. He seemed the least steady of any so far and stumbled on the thirteenth step of the gallows. His only words were, "Long live eternal Germany", before he was hooded and dropped through the trap.[20][21]

His body, along with those of the other nine executed men and the corpse of Hermann Göring, was cremated at the Ostfriedhof Cemetery in Munich, and the ashes were scattered in the river Isar.[22][23][24]

See also

References

- ^ Office of United States Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality (1948). Nazi Conspiracy And Aggression: Supplement B. United States Government Printing Office. p. 408.

- ^ Lisciotto, Carmelo (2007). "SS & Other Nazi Leaders". Holocaust Research Project. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ISBN 0-674-01172-4

- ^ a b "Nazi Germany - Government Structure". Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ISBN 0-582-49200-9.

- ^ Biographie, Deutsche. "Frick, Wilhelm - Deutsche Biographie". www.deutsche-biographie.de.

- ^ a b "Index Fo-Fy". rulers.org.

- ^ "Nurnbergprocessen 1". www.bjornetjenesten.dk. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- ISBN 978-0141009759.

- ^ "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Office of the United States Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality ("Red Series"): Volume 5, pp. 658–659". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Office of the United States Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality ("Red Series"): Volume 5, p. 231, Document 2481-PS". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ISBN 978-3-770-05271-4.

- ^ A legalistic follower, rather than an initiator, Frick the servant increasingly lost favour with his master, apparently because he misunderstood the basic nature of the Fuhrer's governance. Whereas the Third Reich thrived on inconsistencies, rivalries, and constant evolutionary change, Frick's juristic mind longed for order and legal stabilization. The incongruity was insuperable and it was thus logical enough that in 1943 the minister, whose share of practical power had rapidly diminished in the second half of the 1930s, ultimately even lost his official post.Udo Sautter, Canadian Journal of History

- ^ Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life, Oxford University Press, p. 204.

- ^ Williams, Max (2001). Reinhard Heydrich: The Biography: Volume 1, Ulric, p. 77.

- ^ "Hans Mommsen, The Dissolution of the Third Reich (1943–1945)". Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Trial:Wilhelm Frick Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The trial of German major war criminals : proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg Germany". avalon.law.yale.edu.

- ^ "Nuremberg Trial Defendants: Wilhelm Frick". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- ^ Joseph Kingsbury-Smith, who witnessed the execution of Wilhelm Frick and nine other leaders of the Nazi Party on 1st October 1946 Archived 24 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Today, Wilhelm Frick's military dress uniform is on display at Motts Military Museum in Groveport, Ohio. The uniform was found in his home shortly after Frick was arrested in 1945. The soldier who found it and brought it to the US, Richard Roberts, was a member of the CIC (Counter Intelligence Corps). He was an attorney from Columbus, Ohio who spent the war years in espionage and counter intelligence.

- ^ Thomas Darnstädt (2005), "Ein Glücksfall der Geschichte", Der Spiegel, 13 September, no. 14, p. 128

- ^ Manvell 2011, p. 393.

- ^ Overy 2001, p. 205.

Sources

- Manvell, Roger (2011) [1962]. Goering. Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-61608-109-6.

- ISBN 978-0-393-02008-3.

Further reading

External links

Quotations related to Wilhelm Frick at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Wilhelm Frick at Wikiquote Media related to Wilhelm Frick at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wilhelm Frick at Wikimedia Commons- Newspaper clippings about Wilhelm Frick in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW