World War II in the Slovene Lands

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

World War II in the Slovene Lands started in April 1941 and lasted until May 1945. The

Occupation, resistance, collaboration, civil war, and post-war killings

| During World War II, Nazi Germany and Hungary annexed northern areas (brown and dark green areas, respectively), while Fascist Italy annexed the vertically hashed black area (solid black western part being annexed by Italy already with the Treaty of Rapallo). Some villages were incorporated into the Independent State of Croatia. After 1943, Germany took over the Italian occupational area, as well. |

On 6 April 1941,

Under the Nazi occupation

The Germans had a plan of the forced location of the Slovene population in the so called Rann Triangle. The area was the border area towards the Italian occupation zone. The German Gottscheers would have been relocated to that area and would form an ethnic barrier to other Slovene lands. The rest of the Slovene population in Lower Styria was seen as

The majority of Slovene victims during the war were from the northern Slovenia, i.e.

Nazi persecution of the Church

The Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church in annexed Slovenia was akin to

Under Fascist Italy's occupation

Compared to the German policies in the northern Nazi-occupied area of Slovenia and the forced

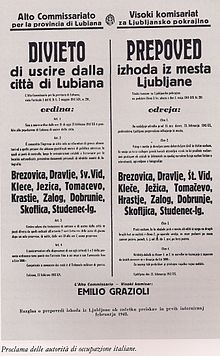

However, after resistance started in

Resistance

On 26 April 1941, several groups formed the

At the very beginning,

In December 1943, Franja Partisan Hospital was built in difficult and rugged terrain, deep inside German-occupied Europe, only a few hours from Austria and the central parts of the Third Reich. German military activity was frequent in the general region throughout the operation of the hospital. It saw continuous improvements until May 1945.

Civil war and post-war killings

In the summer of 1942, a civil war between Slovenes broke out. The two fighting factions were the

Immediately after the war, some 12,000 members of the Slovene Home Guard were killed in the

End of war and aftermath

World War II in the Slovene Lands lasted until the middle of May 1945. On 3 May, the

Croatian occupation of Slovenian territories

After the Invasion of Yugoslavia Slovene lands were divided between Nazi Germany, Italy and Hungary. Some smaller parts were also occupied by Independent State of Croatia. In 1941, five Slovenian settlements came under Croatian rule:

Number of victims

The overall number of World War II casualties in Slovenia is estimated at 97,000. The number includes about 14,000 people who were killed or died for other war-related reasons immediately after the end of the war,, Australia and in the United States.

The overall number of World War Two casualties in Slovenia is estimated to 89,000, while 14,000 people were killed immediately after the end of the war.[12] The overall number of World War II casualties in Slovenia was thus of around 7.2% of the pre-war population, which is above the Yugoslav average, and among the highest percentages in Europe.

Non-extradition of the Italian war criminals

The documents found in British archives by the British historian

See also

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Foibe massacres

- Gonars concentration camp

- Invasion of Yugoslavia

- Italian war crimes

- Maribor prison massacres

- Province of Ljubljana

- Rab concentration camp

- World War II in Yugoslavia

References

- ^ Gregor Joseph Kranjc (2013).To Walk with the Devil, University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, p. introduction 5

- ^ "Bo Slovenija od Hrvaške zahtevala poplačilo vojne škode?". Delo (in Slovenian). 2011-04-12. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- ^ Vincent A. Lapomarda; The Jesuits and the Third Reich; 2nd Edn, Edwin Mellen Press; 2005; pp. 232, 233

- ^ Initial relationship between Italians and Slovenians in 1941

- ^ James H. Burgwyn (2004). General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Volume 9, Number 3, pp. 314-329(16)

- ^ Vurnik, Blaž (22 April 2016). "Kabinet čudes: Ljubljana v žičnem obroču" [Cabinet of Curiosities: Ljubljana in the Barbed Wire Ring]. Delo.si (in Slovenian).

- ISBN 978-1-85065-944-0.

- ISBN 978-1-84176-675-1.

- ISBN 978-1-86011-336-9.

- ISBN 9781576072943.

The former Yugoslavia's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook.

- ^ Slovenski zgodovinski atlas (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 2011), 186.

- ^ a b c Godeša B., Mlakar B., Šorn M., Tominšek Rihtar T. (2002): "Žrtve druge svetovne vojne v Sloveniji". In: Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino, str. 125–130.

- ^ a b "Prvi pravi popis - v vojnem in povojnem nasilju je umrlo 6,5 % Slovencev :: Prvi interaktivni multimedijski portal, MMC RTV Slovenija". Rtvslo.si. 2011-01-13. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ The figure includes the Carinthian Slovene victims.

- ^ Conti, Davide (2011). "Criminali di guerra Italiani". Odradek Edizioni. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ Effie G. H. Pedaliu (2004) Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945-48.Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503-529 (JStor.org preview)

External links

Media related to Slovenia in World War II at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Slovenia in World War II at Wikimedia Commons- "ICH WÄHLE NICHT" (in German).

- Video of the contribution by historian Damijan Guštin, delivered at the Repression during World War II and in the post-war period in Slovenia and in the neighbouring countries international conference, held at the Institute of Contemporary History, Ljubljana, 2012.

- Occupation Borders in Slovenia 1941–1945 (pdf), Ljubljana, University of Ljubljana Press, 2023

- Kornelija Ajlec, Božo Repe: Dismembered Slovenia (pdf), Ljubljana, University of Ljubljana Press, 2023

- Make This Land German ... Italian ... Hungarian ... Croatian! The Role of the Occupation Border in the Denationalization Policy and the Lives of the Slovene Population. Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University in Ljubljana. Web presentation by Institute for contemporaty History. (web exhibition)

- Children of the Border (video made by research project Napravite mi to deželo nemško - italijansko - madžarsko - hrvaško! Vloga okupacijskih meja v raznarodovalni politiki in življenju slovenskega prebivalstva. : Make This Land German ... Italian ... Hungarian ... Croatian! The Role of the Occupation Border in the Denationalization Policy and the Lives of the Slovene Population.)