Wulfstan (died 1023)

Wulfstan | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of York | |

| Appointed | 1002 |

| Term ended | 1023 |

| Predecessor | Ealdwulf |

| Successor | Ælfric Puttoc |

| Other post(s) | |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 996 |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 28 May 1023 York |

| Buried | Ely |

Wulfstan (sometimes Wulfstan II

Besides sermons Wulfstan was also instrumental in drafting law codes for both kings

Life

Wulfstan's early life is obscure, but he was certainly the uncle of one

In 1002 Wulfstan was elected Archbishop of York and was immediately translated to that see.[c] Holding York also brought him control over the diocese of Worcester, as at that time it was practice in England to hold "the potentially disaffected northern archbishopric in plurality with a southern see."[14][d] He held both Worcester and York until 1016, resigning Worcester to Leofsige while retaining York.[15] There is evidence, however, that he retained influence over Worcester even after this time, and that Leofsige perhaps acted "only as a suffragan to Wulfstan."[16] Although holding two or more episcopal sees in plurality was both uncanonical and against the spirit of the Benedictine Reform, Wulfstan had inherited this practice from previous archbishops of York, and he was not the last to hold York and Worcester in plurality.[17][e]

Wulfstan must have early on garnered the favour of powerful men, particularly Æthelred king of England, for we find him personally drafting all royal law codes promulgated under Æthelred's reign from 1005 to 1016.[18] There is no doubt that Wulfstan had a penchant for law; his knowledge of previous Anglo-Saxon law (both royal and ecclesiastical), as well as ninth-century Carolingian law, was considerable. This surely made him a suitable choice for the king's legal draftsman. But it is also likely that Wulfstan's position as archbishop of York, an important centre in the then politically sensitive northern regions of the English kingdom, made him not only a very influential man in the North, but also a powerful ally for the king and his family in the South. It is indicative of Wulfstan's continuing political importance and savvy that he also acted as legal draftsman for, and perhaps advisor to, the Danish king Cnut, who took England's West Saxon throne in 1016.[18]

Homilist

Wulfstan was one of the most distinguished and effective Old English prose writers.

In a series of homilies begun during his tenure as Bishop of London, Wulfstan attained a high degree of competence in rhetorical prose, working with a distinctive rhythmical system based around alliterative pairings. He used intensifying words, distinctive vocabulary and compounds, rhetorical figures, and repeated phrases as literary devices. These devices lend Wulfstan's homilies their tempo-driven, almost feverish, quality, allowing them to build toward multiple climaxes. An example from one of his earliest sermons, titled Secundum Lucam, describes with vivid rhetorical force the unpleasantries of Hell (notice the alliteration, parallelism, and rhyme):

Wa þam þonne þe ær geearnode helle wite. Ðær is ece bryne grimme gemencged, & ðær is ece gryre; þær is granung & wanung & aa singal heof; þær is ealra yrmða gehwylc & ealra deofla geþring. Wa þam þe þær sceal wunian on wite. Betere him wære þæt he man nære æfre geworden þonne he gewurde.[22]

- "Woe then to him who has earned for himself the torments of Hell. There there is everlasting fire roiling painfully, and there there is everlasting filth. There there is groaning and moaning and always constant wailing. There there is every kind of misery, and the press of every kind of devil. Woe to him who dwells in torment: better it were for him that he were never born, than that he become thus."[23]

This type of heavy-handed, though effective, rhetoric immediately made Wulfstan's homilies popular tools for use at the pulpit.[24]

There is good evidence that Wulfstan's homiletic style was appreciated by his contemporaries. While yet bishop of London, in 1002 he received an anonymous letter in Latin praising his style and eloquence. In this letter, an unknown contemporary refuses to do a bit of translation for Wulfstan because he fears he could never properly imitate the Bishop's style.[2] The Chronicle of Ely said of his preaching that "when he spoke, it was as if his listeners were hearing the very wisdom of God Himself."[25] Though they were rhetorically ornate, Wulfstan's homilies show a conscious effort to avoid the intellectual conceits presumably favoured by educated (i.e. monastic) audiences; his target audience was the common English Christian, and his message was suited to everyone who wished to flock to the cathedral to hear it. Wulfstan refused to include in his works confusing or philosophical concepts, speculation, or long narratives – devices which other homilies of the time regularly employed (likely to the dismay of the average parishioner). He also rarely used Latin phrases or words, though a few of his homilies do survive in Latin form, versions that were either drafts for later English homilies, or else meant to be addressed to a learned clergy. Even so, even his Latin sermons employ a straightforward approach to sermonising. Wulfstan's homilies are concerned only with the "bare bones, but these he invests with a sense of urgency of moral or legal rigorism in a time of great danger".[26]

The canon of Wulfstan's homiletic works is somewhat ambiguous, as it is often difficult to tell if a homily in his style was actually written by Wulfstan, or is merely the work of someone who had appreciated Wulfstanian style and imitated it. However, throughout his episcopal career, he is believed to have written upwards of 30 sermons in Old English. The number of his Latin sermons has not yet been established.[f] He may also have been responsible, wholly or in part, for other extant anonymous Old English sermons, for his style can be detected in a range of homiletic texts which cannot be directly attributed to him. However, as mentioned, some scholars believe that Wulfstan's powerful rhetorical style produced imitators, whose homilies would now be difficult to distinguish from genuine Wulfstanian homilies.[28] Those homilies which are certainly by Wulfstan can be divided into 'blocks', that is by subject and theme, and in this way it can be seen that at different points in his life Wulfstan was concerned with different aspects of Christian life in England.[29] The first 'block' was written ca. 996–1002 and is concerned with eschatology, that is, the end of the world. These homilies give frequent descriptions of the coming of Antichrist and the evils that will befall the world before Christ's Second Coming. They likely play on the anxiety that surely developed as the end of the first millennium AD approached. The second 'block', written around 1002–1008, is concerned with the tenets of the Christian faith. The third 'block', written around 1008–1020, concerns archiepiscopal functions. The fourth and final 'block', written around 1014–1023, known as the "Evil Days" 'block', concerns the evils that befall a kingdom and people who do not live proper Christian lives. This final block contains his most famous homily, the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, where Wulfstan rails against the deplorable customs of his time, and sees recent Viking invasions as God's punishment of the English for their lax ways. About 1008 (and again in a revision about 1016) he wrote a lengthy work which, although not strictly homiletic, summarises many of the favourite points he had hitherto expounded upon in his homilies. Titled by modern editors as the Institutes of Polity, it is a piece of 'estates literature' which details, from the perspective of a Christian polity, the duties of each member of society, beginning with the top (the king) and ending at the bottom (common folk).[30]

Language

Wulfstan was a native speaker of Old English. He was also a competent Latinist. As York was at the centre of a region of England that had for some time been colonised by people of Scandinavian descent, it is possible that Wulfstan was familiar with, or perhaps even bilingual in, Old Norse. He may have helped incorporate Scandinavian vocabulary into Old English. Dorothy Whitelock remarks that "the influence of his sojourns in the north is seen in his terminology. While in general he writes a variety of late West Saxon literary language, he uses in some texts words of Scandinavian origin, especially in speaking of the various social classes."[31] In some cases, Wulfstan is the only one known to have used a word in Old English, and in some cases such words are of Scandinavian origin. Some words of his that have been recognised as particularly Scandinavian are þræl "slave, servant" (cf. Old Norse þræll; cp. Old English þeowa), bonda "husband, householder" (cf. Old Norse bondi; cp. Old English ceorl), eorl "nobleman of high rank, (Danish) jarl" (cf. Old Norse jarl; cp. Old English ealdorman), fysan "to make someone ready, to put someone to flight" (cf. Old Norse fysa), genydmaga "close kinsfolk" (cf. Old Norse nauðleyti), and laga "law" (cf. Old Norse lag; cp. Old English æw)[g]

Some Old English words which appear only in works under his influence are werewulf "were-wolf," sibleger "incest," leohtgescot "light-scot" (a tithe to churches for candles), tofesian, ægylde, and morðwyrhta

Church reform and royal service

Wulfstan was very involved in the reform of the English church, and was concerned with improving both the quality of Christian faith and the quality of ecclesiastical administration in his dioceses (especially York, a relatively impoverished diocese at this time). Towards the end of his episcopate in York, he established a small monastery in

In 1009 Wulfstan wrote the edict that Æthelred II issued calling for the whole nation to fast and pray for three days during

Death and legacy

Wulfstan died at York on 28 May 1023. His body was taken for burial to the monastery of Ely, in accordance with his wishes. Miracles are ascribed to his tomb by the Liber Eliensis, but it does not appear that any attempt to declare him a saint was made beyond this.[2] The historian Denis Bethell called him the "most important figure in the English Church in the reigns of Æthelred II and Cnut."[39]

Wulfstan's writings influenced a number of writers in late Old English literature. There are echoes of Wulfstan's writings in the 1087 entry of the

The unique 11th-century manuscript of the Early English Apollonius of Tyre may only have survived because it was bound into a book together with Wulfstan's homilies.[43]

Works

Wulfstan wrote some works in Latin, and numerous works in Old English, then the vernacular.[h] He has also been credited with a few short poems. His works can generally be divided into homiletic, legal, and philosophical categories.

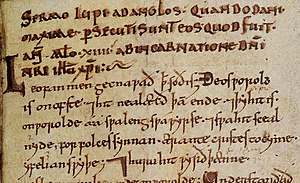

Wulfstan's best-known homily is Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, or Sermon of the Wolf to the English. In it he proclaims the depredations of the "Danes" (who were, at that point, primarily Norwegian invaders) a scourge from

Style

Wulfstan's style is admired by many sources, easily recognisable and exceptionally distinguished. "Much Wulfstan material is, more-over, attributed largely or even solely on the basis of his highly idiosyncratic prose style, in which strings of syntactically independent two-stress phrases are linked by complex patterns of alliteration and other kinds of sound play. Indeed, so idiosyncratic is Wulfstan’s style that he is even ready to rewrite minutely works prepared for him by Ǣlfric".[19] From this identifiable style, 26 sermons can be attributed to Wulfstan, 22 of which are written in Old English, the others in Latin. However, it's suspected that many anonymous materials are Wulfstan's as well, and his handwriting has been found in many manuscripts, supplementing or correcting material.[19] He wrote more than just sermons, including law-codes and sections of prose.

Certainly he must have been a talented writer, gaining a reputation of eloquence while he still lived in London.[55] In a letter to him, "the writer asks to be excused from translating something Wulfstan had asked him to render into English and pleads as an excuse his lack of ability in comparison with the bishop’s skill".[55] Similarly, "[o]ne early student of Wulfstan, Einenkel, and his latest editor, Jost, agree in thinking he wrote verse and not prose" (Continuations, 229). This suggests Wulfstan's writing is not only eloquent, but poetic, and among many of his rhetorical devices is marked rhythm (229). Taking a look at Wulfstan's actual manuscripts, presented by Volume 17 of Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile, it becomes apparent that his writing was exceptionally neat and well structured – even his notes in the margins are well organised and tidy, and his handwriting itself is ornate but readable.[original research?]

Notes

- ^ William of Malmesbury thought that Wulfstan was not a monk, but the Historia Eliensis and Florence of Worcester both claim that he was.

- ^ For these letters see Whitelock Councils and Synods pp. 231–237

- ^ However it is not clear if he immediately relinquished his seat at London: his London successor's signature does not appear until 1004.[13]

- ^ Note that there was once some confusion among scholars as to the exact time Wulfstan was moved from London to Worcester. But, in 1937 Dorothy Whitelock established a general consensus around the date 1002 for his simultaneous promotion to York and Worcester. Nevertheless, a discrepancy in sourcebooks still persists: see, e.g., Fryde Handbook of British Chronology p. 220.

- ^ Chiefly because they have yet to be edited in full. However, an edition is forthcoming from Thomas Hall.[27]

- ^ For discussion, see "Wulfstan's Scandinavian Loanword Usage: An Aspect of the Linguistic Situation in the Late Old English Danelaw" Tadao Kubouchi. For definitions and occurrences, see the Dictionary of Old English Online.

- ^ An up-to-date list is provided by Sara M. Pons-Sanz "A Reconsideration of Wulfstan's use of Norse-Derived Terms: The Case of Þræl" pp. 6–7.

Citations

- ^ Keynes, 'Archbishops and Bishops', p. 563

- ^ a b c d e f Wormald "Wulfstan" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Mack "Changing Thegns" Albion p. 380

- ^ Wormald "Archbishop Wulfstan" p. 13

- ^ Wilcox "Wolf on Shepherds" p. 397

- ^ Williams Æthelred the Unready p. 85

- ^ Wormald "Archbishop Wulfstan" p. 12

- ^ a b Knowles Monastic Order p. 64

- ^ Whitelock "Archbishop Wulfstan" p. 35

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, year 996

- ^ Ashe, Laura. "Viking Apocalypse: The Invasion that Spelled Doom for the Anglo-Saxons". History Extra. BBC. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Wulfstan". Behind the Name. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ a b Whitelock "Note on the Career of Wulfstan the Homilist" p. 464

- ^ Quoted in Wormald "Wulfstan" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 224

- ^ Whitelock "Wulfstan at York" p. 214, and note 2

- ^ a b Wormald "Archbishop Wulfstan" p. 193

- ^ a b Wormald "Æthelred the Lawmaker"

- ^ a b c Orchard "Wulfstan the Homilist" Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England pp. 494–495

- ^ Williams English and the Norman Conquest p. 214

- ISBN 9781843842569. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Bethurum Homilies of Wulfstan p. 126, lines 65–70

- ^ "Saint of the Day Quote: Saint Wulfstan". The American Catholic. 19 January 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Szarmach "Wulfstan of York" Medieval England p. 821

- ^ Quoted in Williams Æthelred the Unready p. 86

- ^ Gatch Preaching and Theology p. 108

- ^ Hall "Wulfstan's Latin Sermons"

- ^ Jost Wulfstanstudien pp. 110–182

- ^ Bethurum Homilies of Wulfstan

- ^ Wulfstan Die 'Institutes of Polity, Civil and Ecclesiastical': Ein Werk Erzbischof Wulfstans von York pp. 39–165

- ^ Whitelock "Wulfstan at York" p. 226

- ^ Knowles Monastic Order p. 70

- ^ Williams Æthelred the Unready pp. 14, 82, 94

- ^ a b Szarmach "Wulfstan of York" Medieval England p. 820

- ^ O'Brien Queen Emma and the Vikings p. 73

- ^ O'Brien Queen Emma and the Vikings pp. 115–118

- ^ O'Brien Queen Emma and the Vikings p. 123

- ^ Williams English and the Norman Conquest p. 156

- ^ Bethell "English Black Monks" English Historical Review p. 684

- ^ Lerer "Old English and its Afterlife" Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature p. 13

- ^ Lerer "Old English and its Afterlife" Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature p. 28

- ^ Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 178

- ^ Goolden, Peter The Old English Apollonius of Tyre Oxford University Press 1958 xxxii–xxxiv

- ^ Hill Road to Hastings p. 47

- ^ Gatch Preaching and Theology p. 105

- ^ Gatch Preaching and Theology p. 116

- ^ Gatch Preaching and Theology Chapter 10

- ^ Williams Æthelred the Unready p. 88

- ^ Wulfstan Homilien

- ^ Wulfstan Sermo Lupi ad Anglos

- ^ Wulfstan The Homilies of Wulfstan

- ^ Wulfstan Wulfstan's Canon Law Collection

- ^ Wormald Making of English Law pp. 355–66

- ^ Wormald "Archbishop Wulfstan:" p. 10

- ^ a b Bethurum Homilies of Wulfstan p. 58.

References

- OCLC 106149.

- Bethell, D. L. (1969). "English Black Monks and Episcopal Elections in the 1120s". .

- Bethurum, Dorothy (1957). The Homilies of Wulfstan. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Blair, John (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 186485136.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 183920684.

- Gatch, Milton McC. (1977). Preaching and Theology in Anglo-Saxon England: AElfric and Wulfstan. Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press.

- Hall, Thomas N. (2004). "Wulfstan's Latin Sermons". In Towened, Matthew (ed.). Wulfstan, Archbishop of York: The Proceedings of the 2nd Alcuin Conference. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 93–139.

- Hill, Paul (2005). The Road to Hastings: The Politics of Power in Anglo-Saxon England. Stroud: Tempus. OCLC 57354405.

- Jost, Karl (1950). Wulfstanstudien. Bern: A. Francke.

- Keynes, Simon (2014). "Appendix II: Archbishops and Bishops 597-1066". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Second ed.). Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 539–66. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- OCLC 156898145.

- Lerer, Seth (1999). "Old English and its Afterlife". In David Wallace (ed.). The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44420-9.

- Mack, Katharin (Winter 1984). "Changing Thegns: Cnut's Conquest and the English Aristocracy". JSTOR 4049386.

- Orchard, Andy (1991). "Wulstan the Homilist". In Lapidge, Michael (ed.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- O'Brien, Harriet (2005). Queen Emma and the Vikings: A History of Power, Love and Greed in Eleventh-Century England. New York: Bloomsbury USA. OCLC 59401757.

- Strayer, Joseph R., ed. (1989). "Wulfstan of York". Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Vol. 1 & 12.

- Szarmach, Paul E.; M Teresa Tavormina; Joel T. Rosenthal, eds. (1998). "Wulfstan of York". Medieval England: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8240-5786-2.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1942). "Archbishop Wulfstan, Homilist and Statesman". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Fourth Series. 24 (24): 25–45. S2CID 162930449.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1981). Councils and Synods, With Other Documents Relating to the English Church, Volume 1: A.D. 871–1204 (pt. 1: 871–1066). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1937). "A Note on the Career of Wulfstan the Homilist". The English Historical Review. lii (52): 460–65. .

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1963). Sermo Lupi Ad Anglos (3rd ed.). London: Methuen.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1965). "Wulfstan at York". In Jess B. Bessinger; Robert P. Creed (eds.). Franciplegius: Medieval and Linguistic Studies in Honor of Francis Peabody Magoun Jr. New York. pp. 214–231.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wilcox, Jonathan. "The Wolf on Shepherds: Wulfstan, Bishops, and the Context of the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos": 395–418.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - OCLC 51780838.

- OCLC 52062791.

- Wormald, Patrick (1978). "Æthelred the Lawmaker". In David Hill (ed.). Ethelred the Unready: Papers from the Millenary Conference. Oxford. pp. 47–80.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wormald, Patrick (1999). "Archbishop Wulfstan and the Holiness of Society". In D. Pelteret (ed.). Anglo-Saxon History: Basic Readings. New York. pp. 191–224.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wormald, Patrick (2004). "Archbishop Wulfstan: Eleventh-Century State-Builder". In Townend, Matthew (ed.). Wulfstan, Archbishop of York: The Proceedings of the 2nd Alcuin Conference. Turnhout. pp. 9–27.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wormald, Patrick (2000). The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century – Volume 1: Legislation and its Limits. Oxford: Blackwell.

- . Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- Wulfstan (1959). Die 'Institutes of Polity, Civil and Ecclesiastical': Ein Werk Erzbischof Wulfstans von York. Swiss Studies in English 47. Jost, Karl (editor). Bern: A. Francke AG Verlag.

- Wulfstan; Bethurum, Dorothy (1957). The Homilies of Wulfstan. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Wulfstan; Napier, Arthur (1883). Sammlung der ihm Zugeschriebenen Homilien nebst Untersuchungen über ihre Echtheit. Berlin: Weidmann.

- Wulfstan (1999). James E. Cross; Andrew Hamer (eds.). Wulfstan's Canon Law Collection. Anglo-Saxon Texts I. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer.

Further reading

- Pons-Sanz, Sara M. Norse-Derived Vocabulary in Late Old English Texts: Wulfstan’s Works, a Case Study. North-Western European Language Evolution Supplement 22. University Press of Southern Denmark, 2007.

External links

- Wulfstan 41 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- Wulfstan's Eschatological Homilies

- Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, translated by M. Bernstein from Manuscript I