XXI Corps (United Kingdom)

| XXI Corps | |

|---|---|

Army Corps | |

| Part of | Egyptian Expeditionary Force |

| Engagements | World War I

|

| Commanders | |

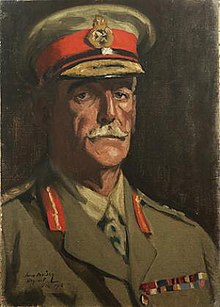

| Notable commanders | Lt-Gen Sir Edward Bulfin |

The XXI Corps was an

Origin

When

Service

Order of Battle, October 1917

The composition of the corps at the beginning of the Third Battle of Gaza was as follows:[6][12][13]

- Corps Headquarters

- General Officer Commanding, Lt-Gen Edward Bulfin

- Brigadier-General, General Staff, Brig-Gen E.T. Humphreys

- Deputy Adjutant and Quartermaster-General, Brig-Gen St. G.B. Armstrong

- 52nd (Lowland) Division, Maj-Gen John Hill

- 54th (East Anglian) Division, Maj-Gen Steuart Hare

- 75th Division, Maj-Gen Philip Palin

- XXI Corps Cavalry Regiment

- A Squadron 1/1st Duke of Lancaster's Own Yeomanry

- A Squadron 1/1st Hertfordshire Yeomanry

- C Squadron 1/1st Queen's Own Royal Glasgow Yeomanry

- Commander, Corps Royal Artillery, Brig-Gen Hugh Simpson-Baikie

- XCVII Heavy Artillery Group, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA)

- 189th and 195th Heavy Batteries

- 201st, 205th, 300th and 380th Siege Batteries

- C Heavy Artillery Group, RGA

- 10th Heavy Battery

- 43rd, 134th, 379th, 422nd and 423rd Siege Batteries

- CII Heavy Artillery Group, RGA

- 202nd Heavy Battery

- 209th, 292nd, 420th, 421st and 424th Siege Batteries

- XCV Heavy Artillery Group, RGA (HQ arrived by March 1918)

- XCVII Heavy Artillery Group, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA)

- Royal Engineers (RE), Chief Engineer, Brig-Gen R.P.T. Hawksley

- XXI Corps Signal Company, RE [9]

- 21 Corps Wireless Section, RE

- XXI Corps Signal Company, RE [9]

- Machine Gun Corps (MGC)

- E Company, MGC (Heavy Branch), became Detachment Tank Corps, EEF

- 211th Machine Gun Company

Invasion of Palestine

The EEF's offensive began with the

The advance then continued and XXI Corps was involved in the following actions:[6]

- Battle of Mughar Ridge:

- Action at Burqa 12 November

- Mughar Ridge 13 November

- Occupation of Junction Station 14 November

- Battle of Nebi Samwil 17–24 November

- Defence of Jerusalem 27–28 November

- Battle of Jaffa 11–22 December:

- Passage of the Nahr el Auja 21 December

- Battle of Tell 'Asur 8–12 March 1918:

- Fight at Ras el 'Ain 12 March

- Action of Berukin9–10 April

Order of Battle, September 1918

Following the

- Corps HQ

- GOC, Lt-Gen Sir Edward Bulfin

- BGGS, Brig-Gen H.F. Salt

- DAQMG, Brig-Gen St. G.B. Armstrong

- 3rd (Lahore) Division, Maj-Gen Reginald Hoskins

- 7th Indian Brigade

- 8th Indian Brigade

- 9th Indian Brigade

- 7th (Meerut) Division Maj-Gen Sir Vere Fane

- 19th Indian Brigade

- 21st Indian Brigade

- 28th Indian Brigade (Frontier Force)

- 54th (East Anglian) Division, Maj-Gen Steuart Hare

- 161st (Essex) Brigade

- 162nd (East Midland) Brigade

- 163rd (Norfolk and Suffolk) Brigade

- Détachement Français de Palestine et de Syrie, Colonel Giles de Piépape

- Régiment de Marche de Tirailleurs

- Régiment de Marche de la Légion d'Orient

- 60th Division, Maj-Gen John Shea

- 75th Division, Maj-Gen Philip Palin

- 232nd Brigade

- 233rd Brigade

- 233rd Brigade

- 5th Australian Light Horse Brigade

- XXI Corps Cavalry Regiment

- A Sqn 1/1st Duke of Lancaster's Own Yeomanry

- A and B Sqns 1/1st Hertfordshire Yeomanry[23]

- Commander, Corps RA, Brig-Gen Hugh Simpson-Baikie

- XCV Brigade, RGA

- 181st Heavy Bty

- 304th, 314th, 383rd and 422nd Siege Btys

- XCVI Brigade, RGA

- 189th and 202nd Heavy Btys

- 378th and 394th Siege Btys

- C Brigade, RGA

- 15th Heavy Bty

- 134th and 334th Siege Btys, sections 43rd and 300th Siege Btys

- CII Brigade, RGA

- 91st Heavy Bty

- 209th, 380th and 440th Siege Btys, sections 43rd and 300th Siege Btys

- VIII Mountain Brigade, RGA

- 11th, 13th and 17th Mountain Btys

- IX Mountain Brigade, RGA

- 10th, 12th and 16th Mountain Btys

- XCV Brigade, RGA

- Royal Engineers, Chief Engineer, Brig-Gen R.P.T. Hawksley

Final Offensive

The Battle of Megiddo was launched on 19 September. XXI Corps, with five infantry divisions and a cavalry brigade, had the task of breaking through Turkish trench lines that in places were5 miles (8.0 km) deep. However, it had overwhelming superiority in artillery and was aided by deception plans. The corps had established a bridging school on the

After the Battle of Sharon XXI Corps' divisions were employed on salvage work and road repair. 54th (EA) Division concentrated at Haifa, 60th and 75th Divisions left the corps and came directly under GHQ, while 3rd (Indian) Division did garrison duty under the DMC. By late September the EEF was closing in on Damascus and ordered XXI Corps to secure the coast and ports of Syria. 7th (Indian) Division, which had already shown remarkable powers of marching, was ordered to march to Beirut along the coast road. Starting on 29 September, the division advanced in three columns, Column A consisted of XXI Corps Cavalry Regiment, a light armoured motor battery (armoured cars), and a single infantry company; the Indian Sapper companies and Pioneer battalion followed with Column B. On 2 October the division was confronted by the Ladder of Tyre, a narrow ancient track consisting of steps cut into the cliff. There was no alternative route. Extensive engineering work would be required to make it passable for wheeled vehicles, with the danger of the whole cliff shelf falling into the sea. After a few minutes' consideration, Bulfin ordered the engineers to begin work. The task of preparing the half-mile (800 m) track took two-and-a-half days, but was successfully completed so that the 60-pounder guns of 15th Heavy Bty, RGA, could get through. Before it was completed, XXI Corps Cavalry Regiment advanced cross-country on 4 October and entered Tyre, where the Royal Navy landed supplies for the columns. On 6 October the advanced troops secured Sidon, where further supplies were landed, and on 8 October they entered Beirut, where Corps HQ was established in the Deutscherhof' Hotel.[6][34][35]

On 11 October Column A was suddenly ordered to occupy Tripoli, 65 miles (105 km) further on, by the evening of 13 October, which it achieved, arriving in moonlight. The leading infantry brigade of 7th (Indian) Division arrived on 18 October, having covered 270 miles (430 km) in 40 days. The leading troops of 54th (EA) Division began arriving on 31 October, the day on which hostilities in the theatre were ended Armistice of Mudros.[6][36][37]

General Officers Commanding

The following officers commanded the corps during its service:[6]

- Lieutenant-General Edward Bulfin 18 August 1917 – 13 June 1918

- Major-General Sir Vere Fane 13 June – 14 August 1918 (acting)

- Major-General Reginald Hoskins 14 August – 19 August 1918 (acting)

- Lieutenant-General Sir Edward Bulfin 19 August – November 1918

See also

- Military history of the United Kingdom

- List of British corps in World War I

- Egyptian Expeditionary Force

Notes

- ^ a b Woodward, p 100

- ^ Falls, p. 509.

- ^ Bullock, p 131.

- ^ Bullock, p. 67.

- ^ Becke, Pt 4, pp. 27–44.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Becke, Pt 4, pp. 251–5.

- ^ Falls, p. 16.

- ^ Perrett.

- ^ a b Lord & Watson, pp. 220, 227.

- ^ Sainsbury, p. 165.

- ^ Bourne.

- ^ Falls, Appendix 2.

- ^ a b Bullock, Appendices.

- ^ Bullock, pp. 73–8.

- ^ Falls, pp. 63–76, 129–37.

- ^ Sainsbury, pp. 165–7.

- ^ Bullock, pp. 113–4.

- ^ Falls, pp. 411–3, 418.

- ^ Bullock, pp. 121–3.

- ^ Falls, pp. 414–21.

- ^ Bullock, p. 127.

- ^ Falls, Appendix 3.

- ^ Sainsbury, p. 171.

- ^ Falls, p. 484.

- ^ a b Watson & Rinaldi, pp. 41–2.

- ^ Falls, p. 510.

- ^ Bullock, pp. 123–4.

- ^ Falls, p. 459.

- ^ Sainsbury, pp. 172–3.

- ^ Bullock, p. 131.

- ^ Falls, pp. 455–6, 464, 469–88.

- ^ Falls, pp. 504–11.

- ^ Sainsbury, pp. 174–6.

- ^ Falls, pp. 509–11, 602–4.

- ^ Sainsbury, pp. 176–7.

- ^ Falls, pp. 605–7.

- ^ Sainsbury, pp. 177–8.

References

- Maj A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 4: The Army Council, GHQs, Armies, and Corps 1914–1918, London: HM Stationery Office, 1944/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-43-6.

- Blenkinsop, L.J.; Rainey, J.W., eds. (1925). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents Veterinary Services. London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 460717714.

- David L. Bullock, Allenby's War: The Palestine-Arabian Campaigns 1916–1918, London: Blandford Press, 1988, ISBN 0-7137-1869-2.

- Capt ISBN 978-1-84574-951-4.

- Capt Cyril Falls, History of the Great War: Military Operations, Egypt and Palestine, Vol II, From June 1917 to the End of the War, Part II, London: HM Stationery Office, 1930/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1-84574-950-7.

- OCLC 220029983.

- Cliff Lord & Graham Watson, Royal Corps of Signals: Unit Histories of the Corps (1920–2001) and its Antecedents, Solihull: Helion, 2003, ISBN 1-874622-92-2.

- William T. Massey, Allenby’s Final Triumph (London: Constable & Co., London 1920)

- Bryan Perrett, Megiddo 1918: The Last Great Cavalry Victory, London: Osprey, 1999, ISBN 1-85532-827-5.

- Lt-Col J.D. Sainsbury, The Hertfordshire Yeomanry: An Illustrated History' 1794–1920', Welwyn: Hertfordshire Yeomanry and Artillery Historical Trust/Hart Books, 1994, ISBN 0-948527-03-X.

- Graham E. Watson & Richard A. Rinaldi, The Corps of Royal Engineers: Organization and Units 1889–2018, Tiger Lily Books, 2018, ISBN 978-171790180-4.

- OCLC 35621223.

- Woodward, David Hell in the Holy Land: World War I in the Middle East Publisher University Press of Kentucky, (2006), ISBN 0-8131-2383-6

External sources

- Bourne, J. M. (2014). "Edward Bulfin". required.)