Yazid I

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | April 680[a] – 11 November 683 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mu'awiya I | ||||

| Successor | Mu'awiya II | ||||

| Born | c. 646 (25 AH)[b] Syria | ||||

| Died | 11 November 683 (aged c. 37) (14 Rabi al-Awwal 64 AH) Huwwarin, Syria | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

Sufyanid | |||||

| Dynasty | Umayyad | ||||

| Father | Mu'awiya I | ||||

| Mother | Maysun bint Bahdal | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Yazid ibn Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan (

During his father's caliphate, Yazid led several campaigns against the Byzantine Empire, including an attack on the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. Yazid's nomination as heir apparent in 676 CE (56 AH) by Mu'awiya was opposed by several Muslim grandees from the Hejaz region, including Husayn and Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr. The two men refused to recognize Yazid following his accession and took sanctuary in Mecca. When Husayn left for Kufa in Iraq to lead a revolt against Yazid, he was killed with his small band of supporters by Yazid's forces in the Battle of Karbala. Husayn's death caused resentment in the Hejaz, where Ibn al-Zubayr called for a consultative assembly to elect a new caliph. The people of Medina, who supported Ibn al-Zubayr, held other grievances toward the Umayyads. After failing to gain the allegiance of Ibn al-Zubayr and the people of the Hejaz through diplomacy, Yazid sent an army to suppress their rebellion. The army defeated the Medinese in the Battle of al-Harra in August 683 and the city was sacked. Afterward, Mecca was besieged for several weeks until the army withdrew as a result of Yazid's death in November 683. The Caliphate fell into a nearly decade-long civil war, ending with the establishment of the Marwanid dynasty (the Umayyad caliph Marwan I and his descendants).

Yazid continued Mu'awiya's decentralized model of governance, relying on his provincial governors and the tribal nobility. He abandoned Mu'awiya's ambitious raids against the Byzantine Empire and strengthened Syria's military defences. No new territories were conquered during his reign. Yazid is considered an illegitimate ruler and a tyrant by many Muslims due to his hereditary succession, the death of Husayn, and his attack on Medina. Modern historians take a milder view, and consider him a capable ruler, albeit less successful than his father.

Early life

Yazid was born in

During his father's caliphate, Yazid led several campaigns against the Byzantine Empire, which the Caliphate had been trying to conquer, including an attack on the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. Sources give several dates for this between 49 AH (669–70 CE) and 55 AH (674–5 CE). Muslim sources offer few details of his role in the campaigns, possibly downplaying his involvement due to the controversies of his later career. He is portrayed in these sources as having been unwilling to participate in the expedition to the chagrin of Mu'awiya, who then forced him to comply.[9] However, two eighth-century non-Muslim sources from al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), the Chronicle of 741 and the Chronicle of 754, both of which likely drew their material from an earlier Arabic work, report that Yazid besieged Constantinople with a 100,000-strong army. Unable to conquer the city, the army captured adjacent towns, acquired considerable loot, and retreated after two years.[10] Yazid also led the hajj (the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca) on several occasions.[11]

Nomination as caliph

The third caliph

Mu'awiya was determined to install Yazid as his successor. The idea was scandalous to Muslims, as hereditary succession had no precedent in Islamic history—earlier caliphs had been elected either by popular support in Medina or by the consultation of the senior

According to the account of

Reign

Mu'awiya died in April 680.

Oaths of allegiance

Upon his accession,[a] Yazid requested and received oaths of allegiance from the governors of the provinces. He wrote to the governor of Medina, his cousin Walid ibn Utba ibn Abi Sufyan, informing him of Mu'awiya's death and instructing him to secure allegiance from Husayn, Ibn al-Zubayr, and Ibn Umar.[36] The instructions contained in the letter were:

Seize Husayn, Abdullah ibn Umar, and Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr to give the oath of allegiance. Act so fiercely that they have no chance to do anything before giving the oath of allegiance.[37]

Walid sought the advice of Marwan, who suggested that Ibn al-Zubayr and Husayn be forced to pay allegiance as they were dangerous, while Ibn Umar should be left alone as he posed no threat. Husayn answered Walid's summon, meeting Walid and Marwan in a semi-private meeting where he was informed of Mu'awiya's death and Yazid's accession. When asked for his oath of allegiance, Husayn responded that giving his allegiance in private would be insufficient and suggested the oath be made in public. Walid agreed, but Marwan insisted that Husayn be detained until he proffered allegiance. Husayn scolded Marwan and left to join his armed retinue, who were waiting nearby in case the authorities attempted to apprehend him. Immediately following Husayn's exit, Marwan admonished Walid, who in turn justified his refusal to harm Husayn by dint of the latter's close relation to Muhammad. Ibn al-Zubayr did not answer the summons and left for Mecca. Walid sent eighty horsemen after him, but he escaped. Husayn too left for Mecca shortly after, without having sworn allegiance to Yazid.

Battle of Karbala

In Mecca Husayn received letters from pro-

Encouraged by Ibn Aqil's letter, Husayn left for Kufa, ignoring warnings from Ibn Umar and Ibn Abbas. The latter reminded him, to no avail, of the Kufans' previous abandonment of his father Ali and his brother Hasan. On the way to the city, he received news of Ibn Aqil's death.[43] Nonetheless, he continued his march towards Kufa. Ibn Ziyad's 4,000-strong army blocked his entry into the city and forced him to camp in the desert of Karbala. Ibn Ziyad would not let Husayn pass without submitting, which Husayn refused to do. Week-long negotiations failed, and in the ensuing hostilities on 10 October 680, Husayn and 72 of his male companions were slain, while his family was taken prisoner.[43][44] The captives and Husayn's severed head were sent to Yazid. According to the accounts of Abu Mikhnaf (d. 774) and Ammar al-Duhni (d. 750–51), Yazid poked Husayn's head with his staff,[45] although others ascribe this action to Ibn Ziyad.[46][e] Yazid treated the captives well and sent them back to Medina after a few days.[45][43]

Revolt of Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr

Following Husayn's death, Yazid faced increased opposition to his rule from Ibn al-Zubayr who declared him deposed. Although publicly he called for a shura to elect a new caliph,

Domestic affairs and foreign campaigns

The style of Yazid's governance was, by and large, a continuation of the model developed by Mu'awiya. He continued to rely on the governors of the provinces and ashraf, as Mu'awiya had, instead of relatives. He retained several of Mu'awiya's officials, including Ibn Ziyad, who was Mu'awiya's governor of Basra, and Sarjun ibn Mansur, a native Syrian Christian, who had served as the head of the fiscal administration under Mu'awiya.[57][55] Like Mu'awiya, Yazid received delegations of tribal notables (wufud) from the provinces to win their support, which would also involve distributing gifts and bribes.[57] The structure of the caliphal administration and military remained decentralised as in Mu'awiya's time. Provinces retained much of their tax revenue and forwarded a small portion to the Caliph.[58] The military units in the provinces were derived from local tribes whose command also fell to the ashraf.[59]

Yazid approved a decrease in taxes on the

Toward the end of his reign, Mu'awiya reached a thirty-year peace agreement with the Byzantines, obliging the Caliphate to pay an annual tribute of 3,000 gold coins, 50 horses, and 50 slaves, and to withdraw Muslim troops from the forward bases they had occupied on the island of Rhodes and the Anatolian coast.[60] Under Yazid, Muslim bases along the Sea of Marmara were abandoned.[61] In contrast to the far-reaching raids against the Byzantine Empire launched under his father, Yazid focused on stabilizing the border with Byzantium.[61] In order to improve Syria's military defences and prevent Byzantine incursions, Yazid established the northern Syrian frontier district of Qinnasrin from what had been a part of Hims, and garrisoned it.[62][61]

Yazid reappointed

Death and succession

Yazid died on 11 November 683 in the central Syrian desert town of Huwwarin, his favourite residence, aged between 35 and 43, and was buried there.[65] Early annalists like Abu Ma'shar al-Madani (d. 778) and al-Waqidi (d. 823) do not give any details about his death. This lack of information seems to have inspired fabrication of accounts by authors with anti-Umayyad leanings, which detail several causes of death, including a horse fall, excessive drinking, pleurisy, and burning.[66] According to the verses by a contemporary poet Ibn Arada, who at the time resided in Khurasan, Yazid died in his bed with a wine cup by his side.[67][66]

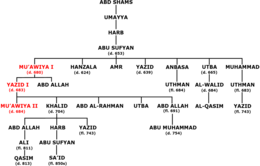

Ibn al-Zubayr subsequently declared himself caliph and Iraq and Egypt came under his rule. In Syria, Yazid's son Mu'awiya II, whom he had nominated, became caliph. His control was limited to parts of Syria as most of the Syrian districts (Hims, Qinnasrin, and Palestine) were controlled by allies of Ibn al-Zubayr.[56] Mu'awiya II died after a few months from an unknown illness. Several early sources state that he abdicated before his death.[67] Following his death, Yazid's maternal Kalbite tribesmen, seeking to maintain their privileges, sought to install Yazid's son Khalid on the throne, but he was considered too young for the post by the non-Kalbites in the pro-Umayyad coalition.[68][69] Consequently, Marwan ibn al-Hakam was acknowledged as caliph in a shura of pro-Umayyad tribes in June 684.[70] Shortly after, Marwan and the Kalb routed the pro-Zubayrid forces in Syria led by Dahhak at the Battle of Marj Rahit.[71] Although the pro-Umayyad shura stipulated that Khalid would succeed Marwan, the latter nominated his son Abd al-Malik as his heir.[68][69] Thus the Sufyanid house, named after Mu'awiya I's father Abu Sufyan, was replaced by the Marwanid house of the Umayyad dynasty.[72] By 692 Abd al-Malik had defeated Ibn al-Zubayr and restored Umayyad authority across the Caliphate.[73]

Legacy

The killing of Muhammad's grandson Husayn caused widespread outcry among Muslims and the image of Yazid suffered greatly.

Traditional Muslim view

Yazid is considered an evil figure by many Muslims to the present day,

Yazid was the first person in the history of the Caliphate to be nominated as heir based on a blood relationship, and this became a tradition afterwards.[25] As such, his accession is considered by the Muslim historical tradition as the corruption of the caliphate into a kingship. He is depicted as a tyrant who was responsible for three major crimes during his caliphate: the death of Husayn and his followers at Karbala, considered a massacre; the aftermath of the Battle of al-Harra, in which Yazid's troops sacked Medina; and the burning of the Ka'ba during the siege of Mecca, which is blamed on Yazid's commander Husayn ibn Numayr. The tradition stresses his habits of drinking, dancing, hunting, and keeping pet animals such as dogs and monkeys, portraying him as impious and unworthy of leading the Muslim community.[57] Extant contemporary Muslim histories describe Yazid as "a sinner in respect of his belly and his private parts", "an arrogant drunken sot", and "motivated by defiance of God, lack of faith in His religion and hostility toward His Messenger".[91] Al-Baladhuri (d. 892) described him as the "commander of the sinners" (amir al-fasiqin), as opposed to the title commander of the faithful (amir al-mu'minin) usually applied to the caliphs.[92] Nevertheless, some historians have argued that there is a tendency in early Muslim sources to exonerate Yazid of blame for Husayn's death, and put the blame squarely on Ibn Ziyad.[43] According to the historian James Lindsay, the Syrian historian Ibn Asakir (d. 1176) attempted to stress Yazid's positive qualities, while accepting the allegations that are generally made against him.[57][93] Ibn Asakir thus emphasised that Yazid was a transmitter of hadith (the sayings and traditions attributed to Muhammad), a virtuous man "by reason of his connection to the age of the Prophet", and worthy of the ruling position.[94]

Modern scholarly view

Despite his reputation in religious circles, academic historians generally portray a more favourable view of Yazid. According to Wellhausen, Yazid was a mild ruler, who resorted to violence only when necessary, and was not the tyrant that the religious tradition portrays him to be. He further notes that Yazid lacked interest in public affairs as a prince, but as a caliph "he seems to have pulled himself together, although he did not give up his old predilections,—wine, music, the chase and other sport".[95] In the view of the historian Hugh N. Kennedy, despite the disasters of Karbala and al-Harra, Yazid's rule was "not devoid of achievement". His reputation might have improved had he lived longer, but his early death played a part in sticking of the stigma of "the shocks of the early part of his reign".[61] According to the Islamicist G. R. Hawting, Yazid tried to continue the diplomatic policies of his father but, unlike Mu'awiya, he was not successful in winning over the opposition with gifts and bribes. In Hawting's summation, "the image of Muʿāwiya as operating more like a tribal s̲h̲ayk̲h̲ than a traditional Middle Eastern despot ... also seems applicable to Yazīd".[57] In the view of Lewis, Yazid was a capable ruler "with much of the ability of his father" but was overly criticized by later Arab historians.[75] Expressing a viewpoint similar to Wellhausen's, Lammens remarked, "a poet himself, and fond of music, he was a Maecenas of poets and artists".[55]

The characterization of Yazid in the Muslim sources has been attributed to the hostility of the

Yazidism

In the

Coins and inscriptions

A

Yazid is thought to be mentioned in a short, undated Paleo-Arabic Christian graffito known as the Yazid inscription. It reads "May God be mindful of Yazid the king".[107][108][109]

Wives and children

Yazid married three women and had several concubines. The names of two of his wives are known: Umm Khalid Fakhita bint Abi Hisham and Umm Kulthum, a daughter of the veteran commander and statesman

Yazid had three sons from his wives. His eldest, Mu'awiya II, was between 17 and 23 years old at the time of Yazid's death. The name of Mu'awiya II's mother is unknown, but she was from the Banu Kalb. Ill health prevented him from carrying out the caliphal duties and he rarely left his residence. He survived his father only by a few months and died without leaving any offspring.

Notes

- ^ Ibn al-Kalbi (d. 819), 21 April according to al-Waqidi (d. 823), and 29 April according to al-Mada'ini (d. 843).[1] Yazid acceded to the caliphate a few days after Mu'awiya's death; according to Abu Mikhnaf (d. 774), his accession was on 7 April, whereas Elijah of Nisibis placed it on 21 April.[2]

- ^ lunar years. The earliest report of his birth is 22 AH, which corresponds to 642–643, and comes closest to the age of 43 years. The historians Henri Lammens and Michael Jan de Goeje both prefer this date. Another report puts his birth in 25 AH, which corresponds to 645–646. The age of 35 years would put his birth year at 29 AH, corresponding to 649.[3][4]

- Abd Allah ibn Abbas's earlier rejection of Yazid's nomination by Mu'awiya are doubted by modern historians who suspect the reports to have been Abbasid efforts to elevate the status of Ibn Abbas, the ancestor of the Abbasid dynasty, and equate him with other prominent leaders of the resistance.[39][40]

- ^ Pro-Alids or Alid partisans were political supporters of Ali, and later of his descendants.[41][42]

- ^ According to Julius Wellhausen, the attribution to Yazid is likely correct as the staff of office was usually held by monarchs.[47] According to Henri Lammens, the deed was likely performed by Ibn Ziyad but the Iraqi chroniclers, whose sympathies lay with Husayn, were only eager to transfer the scene to Damascus.[48]

- ^ Some later Muslim sources assert that the Syrians caused the fire. It is more likely that the defenders caused it accidentally.[53][54][55]

- ^ He wrote a treatise on the subject titled Risala fi jawaz al-la'n ala Yazid (Treatise on the legality of cursing Yazid), and another refuting those who prohibited such practice: Al-radd ali al-muta'sib al-'anid al-mani fi dhamm Yazid (Reply to the stubborn fanatic who forbids condemnation of Yazid).[89]

- ^ Qurayshite descent was considered a prerequisite for the caliphal office by the majority of Muslims in early Islamic history.[106]

- ^ The names of Yazid's sons from his slave women were Abd Allah al-Asghar, Umar, Abu Bakr, Utba, Harb, Abd al-Rahman, al-Rabi and Muhammad.[115]

Citations

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 210.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 139.

- ^ de Goeje 1911, p. 30.

- ^ Lammens 1921, pp. 477–478.

- ^ a b Goldschmidt & Al-Marashi 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Sprengling 1939, pp. 182, 193–194.

- ^ Sprengling 1939, p. 194.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 64.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013, pp. 292–294.

- ^ a b Hawting 2002, pp. 309–311.

- ^ Donner 2010, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Donner 2010, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Donner 2010, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 183.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 322.

- ^ a b Donner 2010, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d Lewis 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 140.

- ^ Hawting 2002, p. 309.

- ^ Marsham 2009, p. 90.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Crone 1980, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Marsham 2009, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d e Kennedy 2016, p. 39.

- ^ a b Lammens 1921, p. 104.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 145.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 46.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 141–145.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 214.

- ^ Kilpatrick 2003, p. 390 n. 54.

- ^ Lammens 1921, p. 108.

- ^ Lammens 1921, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Howard 1990, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Howard 1990, pp. 3–7.

- ^ Marsham 2009, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Sharon 1983, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Donner 2010, p. 178.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e Madelung 2004.

- ^ a b Daftary 1990, p. 50.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1901, p. 67.

- ^ Howard 1990, pp. xiv, 81, 165.

- ^ Wellhausen 1901, p. 67 n..

- ^ Lammens 1921, p. 171.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, pp. 148–150.

- ^ Donner 2010, p. 180.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 152–156.

- ^ Donner 2010, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 48.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c d Lammens 1934, p. 1162.

- ^ a b Donner 2010, pp. 181–182.

- ^ a b c d e f Hawting 2002, p. 310.

- ^ Crone 1980, pp. 30–33.

- ^ Crone 1980, p. 31.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Lammens 1921, p. 327.

- ^ Kennedy 2007, pp. 212–215.

- ^ Kennedy 2007, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Lammens 1921, p. 478.

- ^ a b Lammens 1921, pp. 475–476.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Ullmann 1978, p. 929.

- ^ a b Marsham 2009, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 182.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 91.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 47.

- ^ Hawting 2000, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Donner 2010, p. 179.

- ^ a b Lewis 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Halm 1997, p. 16.

- ^ Fischer 2003, p. 19.

- ^ Hyder 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Hathaway 2003, p. 47.

- ^ a b Fischer 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Aghaie 2004, pp. xi, 9.

- ^ Halm 1997, p. 56.

- ^ Kennedy 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Hyder 2006, pp. 69, 91.

- ^ Aghaie 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Halm 1997, p. 140.

- ^ Hyder 2006, p. 69.

- ^ Kohlberg 2020, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Lammens 1921, pp. 487–488, 492.

- ^ Lammens 1921, p. 490.

- ^ a b c Hoyland 2015, p. 233.

- ^ Lammens 1921, p. 321.

- ^ Lindsay 1997, p. 253.

- ^ Lindsay 1997, p. 254.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 168.

- ^ Lammens 1921, pp. 317–318.

- ^ a b Langer 2010, p. 394.

- ^ Kreyenbroek 2002, p. 313.

- ^ Asatrian & Arakelova 2016, p. 386.

- ^ a b Kreyenbroek 2002, p. 314.

- ^ Mochiri 1982, pp. 137–139.

- ^ a b Mochiri 1982, p. 139.

- ^ Rotter 1982, p. 85.

- ^ Rotter 1982, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Rotter 1982, p. 86.

- ^ Demichelis 2015, p. 108.

- ^ al‐Shdaifat et al. 2017.

- ^ Nehmé 2020.

- ISBN 978-90-04-50064-8, retrieved 21 February 2024

- ^ a b Howard 1990, p. 226.

- ^ a b Bosworth 1993, p. 268.

- ^ Robinson 2020, p. 143.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 222.

- ^ Ahmed 2010, p. 118.

- ^ a b Howard 1990, p. 227.

Sources

- Aghaie, Kamran S. (2004). The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi'i Symbols and Rituals in Modern Iran. Seattle & London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98455-1.

- Ahmed, Asad Q. (2010). The Religious Elite of the Early Islamic Ḥijāz: Five Prosopographical Case Studies. Oxford: University of Oxford Linacre College Unit for Prosopographical Research. ISBN 978-1-900934-13-8.

- Asatrian, Garnik; Arakelova, Victoria (2016). "On the Shi'a Constituent in the Yezidi Religious Lore". Iran and the Caucasus. 20 (3–4): 385–395. JSTOR 44631094.

- ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- ISBN 978-0-521-37019-6.

- de Goeje, Michael Jan (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Demichelis, Marco (2015). "Kharijites and Qarmatians: Islamic Pre-Democratic Thought, a Political-Theological Analysis". In Mattson, Ingrid; Nesbitt-Larking, Paul; Tahir, Nawaz (eds.). Religion and Representation: Islam and Democracy. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 101–127. ISBN 978-1-4438-7059-7.

- ISBN 978-0-674-05097-6.

- ISBN 978-0299184735.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur Jr.; Al-Marashi, Ibrahim (2019). A Concise History of the Middle East. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-62397-2.

- ISBN 1-55876-134-9.

- Hathaway, Jane (2003). A Tale of Two Factions: Myth, Memory, and Identity in Ottoman Egypt and Yemen. New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791486108.

- ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2002). "Yazīd (I) b. Mu'āwiya". In ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Howard, I. K. A., ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XIX: The Caliphate of Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiyah, A.D. 680–683/A.H. 60–64. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0040-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-991637-5.

- Hyder, Syed Akbar (2006). Reliving Karbala: Martyrdom in South Asian Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537302-8.

- Jankowiak, Marek (2013). "The First Arab Siege of Constantinople". In Zuckerman, Constantin (ed.). Travaux et mémoires, Vol. 17: Constructing the Seventh Century. Paris: Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance. pp. 237–320. ISBN 978-2-916716-45-9.

- ISBN 978-0-367-36690-2.

- ISBN 978-0-306-81740-3.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016). Caliphate: The History of an Idea. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465094394.

- Kilpatrick, Hilary (2003). Making the Great Book of Songs: Compilation and the Author's Craft in Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī's Kitāb al-Aghānī. London: Routledge. OCLC 50810677.

- Kohlberg, Etan (2020). In Praise of the Few. Studies in Shiʿi Thought and History. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-9004406971.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (2002). "Yazīdī". In ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- OCLC 474534621.

- Lammens, Henri (1934). "Yazīd b. Mu'āwiya". In Houtsma, M. Th.; Wensinck, A. J.; Gibb, H. A. R.; Heffening, W.; Lévi-Provençal, E. (eds.). The Encyclopædia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples. Vol. IV: S–Z. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 1162–1163.

- Langer, Robert (2010). "Yezidism between Scholarly Literature and Actual Practice: From 'Heterodox' Islam and 'Syncretism' to the Formation of a Transnational Yezidi 'Orthodoxy'". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 37 (3): 393–403. S2CID 145061694.

- ISBN 978-0-19-164716-1.

- OCLC 797598069.

- Lindsay, James E. (1997). "Caliphal and Moral Exemplar? 'Alī Ibn 'Asākir's Portrait of Yazīd b. Mu'āwiya". Der Islam. 74 (2): 250–278. S2CID 163851803.

- ISBN 0-521-64696-0.

- Madelung, Wilferd (2004). "Ḥosayn b. ʿAli I. Life and Significance in Shiʿism". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 7. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Marsham, Andrew (2009). Rituals of Islamic Monarchy: Accession and Succession in the First Muslim Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3077-6.

- Mochiri, Malek Iradj (1982). "A Sasanian-Style Coin of Yazīd B. Mu'āwiya". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 114 (1): 137–141. S2CID 162940912.

- ISBN 978-0-87395-933-9.

- Nehmé, Laïla (2020). "The religious landscape of Northwest Arabia as reflected in the Nabataean, Nabataeo-Arabic, and pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions". Semitica et Classica. 13: 127–154. ISSN 2031-5937.

- Robinson, Majied (2020). Marriage in the Tribe of Muhammad: A Statistical Study of Early Arabic Genealogical Literature. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-062416-8.

- Rotter, Gernot (1982). Die Umayyaden und der zweite Bürgerkrieg (680–692) (in German). Wiesbaden: Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft. ISBN 978-3515029131.

- ISBN 978-965-223-501-5.

- al‐Shdaifat, Younis; Al‐Jallad, Ahmad; al‐Salameen, Zeyad; Harahsheh, Rafe (2017). "An early Christian Arabic graffito mentioning 'Yazīd the king'". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 28 (2): 315–324. ISSN 0905-7196.

- Sprengling, Martin (1939). "From Persian to Arabic". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 56 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 175–224. S2CID 170486943.

- Ullmann, Manfred (1978). "Khālid b. Yazīd b. Muʿāwiya". In OCLC 758278456.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1901). Die religiös-politischen Oppositionsparteien im alten Islam (in German). Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. OCLC 453206240.

- OCLC 752790641.

External links

- Works by Yazid I at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)