Zidovudine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Retrovir, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a687007 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, rectal suppository |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Complete absorption, following first-pass metabolism systemic availability 75% (range 52 to 75%) |

| Protein binding | 30 to 38% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 0.5 to 3 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney and Bile duct |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Zidovudine (ZDV), also known as azidothymidine (AZT), was the first

Common side effects include headaches, fever, and nausea.

Zidovudine was first described in 1964.

Medical uses

HIV treatment

AZT was usually dosed twice a day in combination with other antiretroviral therapies. This approach is referred to as Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (

HIV prevention

AZT has been used for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) in combination with another antiretroviral drug called lamivudine. Together they work to substantially reduce the risk of HIV infection following the first single exposure to the virus.[15] More recently, AZT has been replaced by other antiretrovirals such as tenofovir to provide PEP.[16] Before tenofovir, a principal part of the

During 1994 to 1999, AZT was the primary form of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. AZT prophylaxis prevented more than 1000 parental and infant deaths from AIDS in the United States.

Antibacterial properties

Zidovudine also has antibacterial properties,

Side effects

Most common side effects include nausea, vomiting,

Early long-term higher-dose therapy with AZT was initially associated with side effects that sometimes limited therapy, including

Viral resistance

Even at the highest doses that can be tolerated in patients, AZT is not potent enough to prevent all HIV replication and may only slow the replication of the virus and progression of the disease. Prolonged AZT treatment can lead to HIV developing resistance to AZT by

Mechanism of action

AZT is a thymidine analogue. AZT works by selectively inhibiting HIV's reverse transcriptase, the enzyme that the virus uses to make a DNA copy of its RNA. Reverse transcription is necessary for production of HIV's double-stranded DNA, which would be subsequently integrated into the genetic material of the infected cell (where it is called a provirus).[40][41][42]

Cellular enzymes convert AZT into the effective 5'-triphosphate form. Studies have shown that the termination of HIV's forming DNA chains is the specific factor in the inhibitory effect.[43]

At very high doses, AZT's triphosphate form may also inhibit

Chemistry

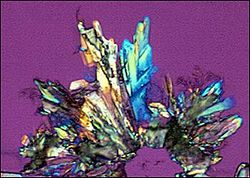

Enantiopure AZT crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21. The primary intermolecular bonding motif is a hydrogen bonded dimeric ring formed from two N-H...O interactions.[51][52]

History

Initial cancer research

In the 1960s, the theory that most

In parallel work, other compounds that successfully blocked the synthesis of nucleic acids had been proven to be both antibacterial, antiviral, and anticancer agents, the leading work being done at the laboratory of Nobel laureates

Richard E. Beltz first synthesized AZT in 1961, but did not publish his research.

This report attracted little interest from other researchers as the Friend leukemia virus is a retrovirus, and at the time, there were no known human diseases caused by retroviruses.[62]

HIV/AIDS research

In 1983, researchers at the Institut Pasteur in Paris identified the retrovirus now known as the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) as the cause of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in humans.[63][64] Shortly thereafter, Samuel Broder, Hiroaki Mitsuya, and Robert Yarchoan of the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI) initiated a program to develop therapies for HIV/AIDS.[65] Using a line of CD4+ T cells that they had made, they developed an assay to screen drugs for their ability to protect CD4+ T cells from being killed by HIV. In order to expedite the process of discovering a drug, the NCI researchers actively sought collaborations with pharmaceutical companies having access to libraries of compounds with potential antiviral activity.[40] This assay could simultaneously test both the anti-HIV effect of the compounds and their toxicity against infected T cells.

In June 1984, Burroughs-Wellcome virologist Marty St. Clair set up a program to discover drugs with the potential to inhibit HIV replication. Burroughs-Wellcome had expertise in nucleoside analogs and viral diseases, led by researchers including

In February 1985, the NCI scientists found that AZT had potent efficacy in vitro.[40][57] Several months later, a phase 1 clinical trial of AZT at the NCI was initiated at the NCI and Duke University.[41][46][66] In doing this Phase I trial, they built on their experience in doing an earlier trial, with suramin, another drug that had shown effective anti-HIV activity in the laboratory. This initial trial of AZT proved that the drug could be safely administered to patients with HIV, that it increased their CD4 counts, restored T cell immunity as measured by skin testing, and that it showed strong evidence of clinical effectiveness, such as inducing weight gain in AIDS patients. It also showed that levels of AZT that worked in vitro could be injected into patients in serum and suppository form, and that the drug penetrated deeply only into infected brains.

Patent filed and FDA approval

A flawed

AZT was subsequently approved unanimously for infants and children in 1990.[71] AZT was initially administered in significantly higher dosages than today, typically 400 mg every four hours, day and night, compared to modern dosage of 300 mg twice daily.[72] The paucity of alternatives for treating HIV/AIDS at that time unambiguously affirmed the health risk/benefit ratio, with inevitable slow, disfiguring, and painful death from HIV outweighing the drug's side effect of transient anemia and malaise.

Society and culture

Until 1991, 80% of the $420 million allocated to the National Institute of Health's AIDS Clinical Trials Group, went toward studies of AZT. Aside from two similarly designed chemotherapies, ddI and ddC, from approval of the drug until 1993, no other drugs against AIDS were approved, leading to criticism that research preoccupation with AZT and its close relatives, and the massive diverting of funds to such, had delayed the development of more efficacious drugs.[8]

In 1991, the advocacy group

In 2002, another lawsuit was filed challenging the patent by the

GSK's patents on AZT expired in 2005, and in September 2005, the FDA approved three generic versions.[76]

References

- FDA. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Retrovir 100mg Capsules – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). December 14, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Retrovir – zidovudine capsule Retrovir – zidovudine solution Retrovir – zidovudine injection, solution". DailyMed. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Active substance: Zidovudine" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. November 30, 2017.

- ^ "Zidovudine". PubChem Public Chemical Database. NCBI. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Zidovudine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ISBN 9783527607495. Archivedfrom the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Linda Marsa, 'Toxic Hope', Los Angeles Times, 20 June 1993

- ISBN 9783764377830.

- hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- PMID 7508227.

- PMID 3072667.

- S2CID 204952772.

- PMID 16195697.

- ^ "UK guideline for the use of post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV following sexual exposure (2011)". Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ "Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health" (PDF). AIDSinfo. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. November 17, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 22, 2006. Retrieved March 29, 2006.

- PMID 17476315.

- ^ Science Codex.

- ^ CIDRZ. Prevention of AIDS Transmission (PMTCT). "Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) | CIDRZ". Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ Transmission of HIV from infants "Transmission of HIV from infants to women who breastfeed them". Aids Perspective. July 1, 2012. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- S2CID 13457499.

- PMID 16741877.

- S2CID 8293828.

- ^ S2CID 26027925.

- PMID 33053176.

- PMID 33020156.

- S2CID 234791392.

- ^ "zidovudine, Retrovir". Medicinenet.com. August 12, 2010. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- S2CID 13539181.

- S2CID 2044833.

- S2CID 26177904.

- S2CID 2829677.

- ^ "ZIDOVUDINE (AZT) – ORAL (Retrovir) side effects, medical uses, and drug interactions". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on June 30, 2005. Retrieved January 9, 2006.

- ^ Side Effects. NAM Aidsmap. "Zidovudine (AZT, Retrovir)". Archived from the original on December 26, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ "Summary of Data Reported and Evaluation". 2000. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ^ "State of California Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Hazard Assessment Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986 Chemicals Known to the State to Cause Cancer or Reproductive Toxicity July 29, 1011" (PDF). July 29, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- PMID 2186629.

- PMID 15855480.

- ^ PMID 2413459.

- ^ S2CID 37985276.

- PMID 1699273.

- PMID 10400767.

- PMID 2430286.

- ^ Induction of Endogenous Virus and of Thymidline Kinase. "Induction of Endogenous Virus and of Thymidline Kinase by Bromodeoxyuridine in Cell Cultures Transformed by Friend Virus" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ PMID 2671731.

- S2CID 20020419.

- PMID 1703154.

- ISBN 978-0-443-05974-2.

- from the original on September 21, 2007.

- PMID 3271074.

- PMID 2446321.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1975". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017.

- ^ "The Purine Path To Chemotherapy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2017.

- ^ Marsa L (June 20, 1993). "Toxic Hope: Widely Embraced, the AIDS Drug is now under Heavy Fire". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Brinck A. "Inventing AZT" (PDF).

- ^ PMID 20018391.

- .

- ^ Detours V; Henry D (writers/directors) (2002). I am alive today (history of an AIDS drug) (Film). ADR Productions/Good & Bad News.

- ^ "A Failure Led to Drug Against AIDS". The New York Times. September 20, 1986. Archived from the original on August 16, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- PMID 4531031.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-89980-8.

- PMID 8493571.

- PMID 18947296.

- ^ NIH Clinical Center's 50th Anniversary. "Clinical Center 50th Anniversary Celebration" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- S2CID 37985276.

- ^ "Did Controversial AZT Treatment Kill More Patients than AIDS in '80s, '90s?". September 21, 2021.

- PMID 3299089.

- PMID 3306004.

- ^ Cimons M (March 21, 1987). "U.S. Approves Sale of AZT to AIDS Patients". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ AZT Approved for AIDS Children. "HEALTH : AZT Approved for AIDS Children". Los Angeles Times. May 3, 1990. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2012 – via From Times Wire Services.

- ^ "Zidovudine (AZT) | Johns Hopkins ABX Guide".

- ^ Greenhouse L (January 17, 1996). "Supreme Court Roundup;Justices Reject Challenge Of Patent for AIDS Drug". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016.

- PMID 24900477.

- ^ a b Meland M (May 3, 2004). "Judge Denies Request To Dismiss Patent Challenge Vs. Glaxo's AZT – Law360". Law360. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016.

- ^ "HIV/AIDS History of Approvals – HIV/AIDS Historical Time Line 2000 – 2010". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). August 8, 2014. Archived from the original on October 23, 2016.

External links

- "Zidovudine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.