Zoonosis

A zoonosis (

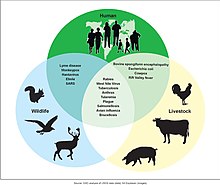

Major modern diseases such as Ebola and salmonellosis are zoonoses. HIV was a zoonotic disease transmitted to humans in the early part of the 20th century, though it has now evolved into a separate human-only disease.[4][5][6] Human infection with animal influenza viruses is rare, as they do not transmit easily to or among humans.[7] However, avian and swine influenza viruses in particular possess high zoonotic potential,[8] and these occasionally recombine with human strains of the flu and can cause pandemics such as the 2009 swine flu.[9] Taenia solium infection is one of the neglected tropical diseases with public health and veterinary concern in endemic regions.[10] Zoonoses can be caused by a range of disease pathogens such as emergent viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites; of 1,415 pathogens known to infect humans, 61% were zoonotic.[11] Most human diseases originated in non-humans; however, only diseases that routinely involve non-human to human transmission, such as rabies, are considered direct zoonoses.[12]

Zoonoses have different modes of transmission. In direct zoonosis the disease is directly transmitted from non-humans to humans through media such as air (influenza) or bites and saliva (rabies).

Host genetics plays an important role in determining which non-human viruses will be able to make copies of themselves in the human body. Dangerous non-human viruses are those that require few mutations to begin replicating themselves in human cells. These viruses are dangerous since the required combinations of mutations might randomly arise in the natural reservoir.[15]

Causes

The emergence of zoonotic diseases originated with the domestication of animals.[16] Zoonotic transmission can occur in any context in which there is contact with or consumption of animals, animal products, or animal derivatives. This can occur in a companionistic (pets), economic (farming, trade, butchering, etc.), predatory (hunting, butchering, or consuming wild game), or research context.[17]

Recently, there has been a rise in frequency of appearance of new zoonotic diseases. "Approximately 1.67 million undescribed viruses are thought to exist in

Contamination of food or water supply

The most significant zoonotic pathogens causing foodborne diseases are Escherichia coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Caliciviridae, and Salmonella.[21][22][23]

In 2006 a conference held in Berlin focused on the issue of zoonotic pathogen effects on

Many food-borne outbreaks can be linked to zoonotic pathogens. Many different types of food that have an animal origin can become contaminated. Some common food items linked to zoonotic contaminations include eggs, seafood, meat, dairy, and even some vegetables.[25]

Outbreaks involving contaminated food should be handled in preparedness plans to prevent widespread outbreaks and to efficiently and effectively contain outbreaks.[26]

Farming, ranching and animal husbandry

Contact with farm animals can lead to disease in farmers or others that come into contact with infected farm animals.

A July 2020 report by the

Wildlife trade or animal attacks

The wildlife trade may increase spillover risk because it directly increases the number of interactions across animal species, sometimes in small spaces.[35] The origin of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic[36][37] is traced to the wet markets in China.[38][39][40][41]

Zoonotic disease emergence is demonstrably linked to the consumption of wildlife meat, exacerbated by human encroachment into natural habitats and amplified by the unsanitary conditions of wildlife markets.[42] These markets, where diverse species converge, facilitate the mixing and transmission of pathogens, including those responsible for outbreaks of HIV-1,[43] Ebola,[44] and mpox,[45] and potentially even the COVID-19 pandemic.[46] Notably, small mammals often harbor a vast array of zoonotic bacteria and viruses,[47] yet endemic bacterial transmission among wildlife remains largely unexplored. Therefore, accurately determining the pathogenic landscape of traded wildlife is crucial for guiding effective measures to combat zoonotic diseases and documenting the societal and environmental costs associated with this practice.

Insect vectors

- African sleeping sickness

- Dirofilariasis

- Eastern equine encephalitis

- Japanese encephalitis

- Saint Louis encephalitis

- Scrub typhus

- Tularemia

- Venezuelan equine encephalitis

- West Nile fever

- Western equine encephalitis

- Zika fever

Pets

Pets can transmit a number of diseases. Dogs and cats are routinely vaccinated against

Pets may also serve as a reservoir of viral disease and contribute to the chronic presence of certain viral diseases in the human population. For instance, approximately 20% of domestic dogs, cats, and horses carry anti-hepatitis E virus

Exhibition

Hunting and bushmeat

Hunting involves humans tracking, chasing, and capturing wild animals, primarily for food or materials like fur. However, other reasons like pest control or managing wildlife populations can also exist. Transmission of zoonotic diseases, those leaping from animals to humans, can occur through various routes: direct physical contact, airborne droplets or particles, bites or vector transport by insects, oral ingestion, or even contact with contaminated environments.[57] Wildlife activities like hunting and trade bring humans closer to dangerous zoonotic pathogens, threatening global health.[58]

According to the Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) hunting and consuming wild animal meat ("bushmeat") in regions like Africa can expose people to infectious diseases due to the types of animals involved, like bats and primates. Unfortunately, common preservation methods like smoking or drying aren't enough to eliminate these risks.[59] Although bushmeat provides protein and income for many, the practice is intricately linked to numerous emerging infectious diseases like Ebola, HIV, and SARS, raising critical public health concerns.[58]

A review published in 2022 found evidence that zoonotic spillover linked to wildmeat consumption has been reported across all continents.[60]

Deforestation, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation

Joshua Moon, Clare Wenham, and Sophie Harman said that there is evidence that decreased biodiversity has an effect on the diversity of hosts and frequency of human-animal interactions with potential for pathogenic spillover.[63]

An April 2020 study, published in the

In October 2020, the

Climate change

According to a report from the

A 2022 study dedicated to the link between climate change and zoonosis found a strong link between climate change and the epidemic emergence in the last 15 years, as it caused a massive migration of species to new areas, and consequently contact between species which do not normally come in contact with one another. Even in a scenario with weak climatic changes, there will be 15,000 spillover of viruses to new hosts in the next decades. The areas with the most possibilities for spillover are the mountainous tropical regions of Africa and southeast Asia. Southeast Asia is especially vulnerable as it has a large number of bat species that generally do not mix, but could easily if climate change forced them to begin migrating.[70]

A 2021 study found possible links between climate change and transmission of COVID-19 through bats. The authors suggest that climate-driven changes in the distribution and robustness of bat species harboring coronaviruses may have occurred in eastern Asian hotspots (southern China, Myanmar, and Laos), constituting a driver behind the evolution and spread of the virus.[71][72]

Secondary transmission

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020) |

- Ebola and viral hemorrhagic disease.

History

During most of human

Many diseases, even epidemic ones, have zoonotic origin and measles, smallpox, influenza, HIV, and diphtheria are particular examples.[77][78] Various forms of the common cold and tuberculosis also are adaptations of strains originating in other species.[citation needed] Some experts have suggested that all human viral infections were originally zoonotic.[79]

Zoonoses are of interest because they are often previously unrecognized diseases or have increased virulence in populations lacking immunity. The West Nile virus first appeared in the United States in 1999, in the New York City area. Bubonic plague is a zoonotic disease,[80] as are salmonellosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Lyme disease.

A major factor contributing to the appearance of new zoonotic pathogens in human populations is increased contact between humans and wildlife.[81] This can be caused either by encroachment of human activity into wilderness areas or by movement of wild animals into areas of human activity. An example of this is the outbreak of Nipah virus in peninsular Malaysia, in 1999, when intensive pig farming began within the habitat of infected fruit bats.[82] The unidentified infection of these pigs amplified the force of infection, transmitting the virus to farmers, and eventually causing 105 human deaths.[83]

Similarly, in recent times avian influenza and West Nile virus have spilled over into human populations probably due to interactions between the carrier host and domestic animals.[citation needed] Highly mobile animals, such as bats and birds, may present a greater risk of zoonotic transmission than other animals due to the ease with which they can move into areas of human habitation.

Because they depend on the human host

Use in vaccines

The first vaccine against smallpox by Edward Jenner in 1800 was by infection of a zoonotic bovine virus which caused a disease called cowpox.[86] Jenner had noticed that milkmaids were resistant to smallpox. Milkmaids contracted a milder version of the disease from infected cows that conferred cross immunity to the human disease. Jenner abstracted an infectious preparation of 'cowpox' and subsequently used it to inoculate persons against smallpox. As a result of vaccination, smallpox has been eradicated globally, and mass inoculation against this disease ceased in 1981.[87] There are a variety of vaccine types, including traditional inactivated pathogen vaccines, subunit vaccines, live attenuated vaccines. There are also new vaccine technologies such as viral vector vaccines and DNA/RNA vaccines, which include many of the COVID-19 vaccines.[88]

Lists of diseases

| Disease[89] | Pathogen(s) | Animals involved | Mode of transmission | Emergence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

African sleeping sickness

|

Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense

|

range of wild animals and domestic livestock | transmitted by the bite of the tsetse fly | 'present in Africa for thousands of years' – major outbreak 1900–1920, cases continue (sub-Saharan Africa, 2020) |

| Angiostrongyliasis | Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Angiostrongylus costaricensis | rats, cotton rats | consuming raw or undercooked snails, slugs, other mollusks, crustaceans, contaminated water, and unwashed vegetables contaminated with larvae | |

Anisakiasis

|

Anisakis | whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, other marine animals | eating raw or undercooked fish and squid contaminated with eggs | |

| Anthrax | Bacillus anthracis | commonly – grazing herbivores such as cattle, sheep, goats, camels, horses, and pigs | by ingestion, inhalation or skin contact of spores | |

| Babesiosis | Babesia spp. | mice, other animals | tick bite | |

| Baylisascariasis | Baylisascaris procyonis | raccoons | ingestion of eggs in feces | |

| Barmah Forest fever | Barmah Forest virus | kangaroos, wallabies, opossums | mosquito bite | |

| Avian influenza | Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 | wild birds, domesticated birds such as chickens[90] | close contact | 2003–present avian influenza in Southeast Asia and Egypt |

| Bovine spongiform encephalopathy | Prions | cattle | eating infected meat | isolated similar cases reported in ancient history; in recent UK history probable start in the 1970s[91] |

| Brucellosis | Brucella spp. | cattle, goats, pigs, sheep | infected milk or meat | historically widespread in Mediterranean region; identified early 20th century |

| Bubonic plague, Pneumonic plague, Septicemic plague, Sylvatic plague | Yersinia pestis | rabbits, hares, rodents, ferrets, goats, sheep, camels | flea bite | epidemics like Black Death in Europe around 1347–53 during the Late Middle Age; third plague pandemic in China-Qing dynasty and India alone |

| Capillariasis | Capillaria spp. | rodents, birds, foxes | eating raw or undercooked fish, ingesting embryonated eggs in fecal-contaminated food, water, or soil | |

| Cat-scratch disease | Bartonella henselae | cats | bites or scratches from infected cats | |

| Chagas disease | Trypanosoma cruzi | armadillos, Triatominae (kissing bug)

|

Contact of mucosae or wounds with feces of kissing bugs. Accidental ingestion of parasites in food contaminated by bugs or infected mammal excretae. | |

Clamydiosis / Enzootic abortion

|

Chlamydophila abortus

|

domestic livestock, particularly sheep | close contact with postpartum ewes | |

| suspected: COVID-19 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

|

suspected: | respiratory transmission | 2019–present COVID-19 pandemic; ongoing pandemic |

| Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease | PrPvCJD

|

cattle | eating meat from animals with Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) | 1996–2001: United Kingdom |

| Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever | Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever orthonairovirus

|

cattle, goats, sheep, birds, multimammate rats, hares | tick bite, contact with bodily fluids | |

| Cryptococcosis | Cryptococcus neoformans | commonly – birds like pigeons | inhaling fungi | |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Cryptosporidium spp. | cattle, dogs, cats, mice, pigs, horses, deer, sheep, goats, rabbits, leopard geckos, birds | ingesting cysts from water contaminated with feces | |

| Cysticercosis and taeniasis | Taenia solium, Taenia asiatica, Taenia saginata | commonly – pigs and cattle | consuming water, soil or food contaminated with the tapeworm eggs (cysticercosis) or raw or undercooked pork contaminated with the cysticerci (taeniasis) | |

| Dirofilariasis | Dirofilaria spp. | dogs, wolves, coyotes, foxes, jackals, cats, monkeys, raccoons, bears, muskrats, rabbits, leopards, seals, sea lions, beavers, ferrets, reptiles | mosquito bite | |

Western equine encephalitis

|

Eastern equine encephalitis virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, Western equine encephalitis virus

|

horses, donkeys, zebras, birds | mosquito bite | |

haemorrhagic fever )

|

Ebolavirus spp. | chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, fruit bats, monkeys, shrews, forest antelope and porcupines | through body fluids and organs | 2013–16; possible in Africa |

| Other haemorrhagic fevers (Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, Dengue fever, Lassa fever, Marburg viral haemorrhagic fever, Rift Valley fever[93]) | Varies – commonly viruses

|

varies (sometimes unknown) – commonly camels, rabbits, hares, hedgehogs, cattle, sheep, goats, horses and swine | infection usually occurs through direct contact with infected animals | 2019–20 dengue fever

|

| Echinococcosis | Echinococcus spp. | commonly – dogs, foxes, jackals, wolves, coyotes, sheep, pigs, rodents | ingestion of infective eggs from contaminated food or water with feces of an infected definitive host | |

| Fasciolosis | Fasciola hepatica, Fasciola gigantica | sheep, cattle, buffaloes | ingesting contaminated plants | |

| Fasciolopsiasis | Fasciolopsis buski

|

pigs | eating raw vegetables such as water spinach | |

diarrheal diseases )

|

Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Listeria spp., Shigella spp. and Trichinella spp. | animals domesticated for food production (cattle, poultry) | raw or undercooked food made from animals and unwashed vegetables contaminated with feces | |

| Giardiasis | Giardia lamblia

|

beavers, other rodents, raccoons, deer, cattle, goats, sheep, dogs, cats | ingesting spores and cysts in food and water contaminated with feces | |

| Glanders | Burkholderia mallei. | horses, donkeys | direct contact | |

| Gnathostomiasis | Gnathostoma spp. | dogs, minks, opossums, cats, lions, tigers, leopards, raccoons, poultry, other birds, frogs | raw or undercooked fish or meat | |

Hantavirus

|

Hantavirus spp.

|

deer mice, cotton rats and other rodents | exposure to feces, urine, saliva or bodily fluids | |

| Henipavirus | Henipavirus spp. | horses, bats | exposure to feces, urine, saliva or contact with sick horses | |

| Hepatitis E | Hepatitis E virus

|

domestic and wild animals | contaminated food or water | |

| Histoplasmosis | Histoplasma capsulatum | birds, bats | inhaling fungi in guano | |

| HIV | SIV Simian immunodeficiency virus | non-human primates | Blood | Immunodeficiency resembling human AIDS was reported in captive monkeys in the United States beginning in 1983.[94][95][96] SIV was isolated in 1985 from some of these animals, captive rhesus macaques who had simian AIDS (SAIDS).[95] The discovery of SIV was made shortly after HIV-1 had been isolated as the cause of AIDS and led to the discovery of HIV-2 strains in West Africa. HIV-2 was more similar to the then-known SIV strains than to HIV-1, suggesting for the first time the simian origin of HIV. Further studies indicated that HIV-2 is derived from the SIVsmm strain found in sooty mangabeys, whereas HIV-1, the predominant virus found in humans, is derived from SIV strains infecting chimpanzees (SIVcpz) |

| Japanese encephalitis | Japanese encephalitis virus

|

pigs, water birds | mosquito bite | |

| Kyasanur Forest disease | Kyasanur Forest disease virus

|

rodents, shrews, bats, monkeys | tick bite | |

| La Crosse encephalitis | La Crosse virus | chipmunks, tree squirrels | mosquito bite | |

| Leishmaniasis | Leishmania spp. | dogs, rodents, other animals[97][98] | sandfly bite | 2004 Afghanistan |

| Leprosy | Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium lepromatosis | armadillos, monkeys, rabbits, mice[99] | direct contact, including meat consumption. However, scientists believe most infections are spread human to human.[99][100] | |

| Leptospirosis | Leptospira interrogans | rats, mice, pigs, horses, goats, sheep, cattle, buffaloes, opossums, raccoons, mongooses, foxes, dogs | direct or indirect contact with urine of infected animals | 1616–20 New England infection; present day in the United States |

| Lassa fever | Lassa fever virus

|

rodents | exposure to rodents | |

| Lyme disease | Borrelia burgdorferi | deer, wolves, dogs, birds, rodents, rabbits, hares, reptiles | tick bite | |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis | Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

|

rodents | exposure to urine, feces, or saliva | |

| Melioidosis | Burkholderia pseudomallei | various animals | direct contact with contaminated soil and surface water | |

| Microsporidiosis | Encephalitozoon cuniculi | Rabbits, dogs, mice, and other mammals

|

ingestion of spores | |

Middle East respiratory syndrome

|

MERS coronavirus

|

bats, camels | close contact | 2012–present: Saudi Arabia |

| Mpox | Monkeypox virus | rodents, primates | contact with infected rodents, primates, or contaminated materials | |

| Nipah virus infection | Nipah virus (NiV) | bats, pigs | direct contact with infected bats, infected pigs | |

| Orf | Orf virus

|

goats, sheep | close contact | |

| Powassan encephalitis | Powassan virus | ticks | tick bites | |

| Psittacosis | Chlamydophila psittaci

|

macaws, cockatiels, budgerigars, pigeons, sparrows, ducks, hens, gulls and many other bird species | contact with bird droplets | |

| Q fever | Coxiella burnetii | livestock and other domestic animals such as dogs and cats | inhalation of spores, contact with bodily fluid or faeces | |

| Rabies | Rabies virus | commonly – dogs, bats, monkeys, raccoons, foxes, skunks, cattle, goats, sheep, wolves, coyotes, groundhogs, horses, mongooses and cats | through saliva by biting, or through scratches from an infected animal | Variety of places like Oceanic, South America, Europe; year is unknown |

| Rat-bite fever | Streptobacillus moniliformis, Spirillum minus | rats, mice | bites of rats but also urine and mucus secretions | |

| Rift Valley fever | Phlebovirus | livestock, buffaloes, camels | mosquito bite, contact with bodily fluids, blood, tissues, breathing around butchered animals or raw milk | 2006–07 East Africa outbreak |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Rickettsia rickettsii | dogs, rodents | tick bite | |

| Ross River fever | Ross River virus | kangaroos, wallabies, horses, opossums, birds, flying foxes | mosquito bite | |

| Saint Louis encephalitis | Saint Louis encephalitis virus

|

birds | mosquito bite | |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

|

SARS coronavirus

|

bats, civets | close contact, respiratory droplets | 2002–04 SARS outbreak ; began in China

|

| Smallpox | Variola virus

|

Possible Monkeys or horses | Spread to person to person quickly | The last case was in 1977; certified by WHO to be eradicated (i.e., eliminated worldwide) as of 1980. |

| Swine influenza | A new strain of the influenza virus endemic in pigs (excludes H1N1 swine flu, which is a human virus)[clarification needed] | pigs | close contact | 2009–10; 2009 swine flu pandemic; began in Mexico. |

| Taenia crassiceps infection | Taenia crassiceps | wolves, coyotes, jackals, foxes | contact with soil contaminated with feces | |

| Toxocariasis | Toxocara spp.

|

dogs, foxes, cats | ingestion of eggs in soil, fresh or unwashed vegetables or undercooked meat | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | cats, livestock, poultry | exposure to cat feces, organ transplantation, blood transfusion, contaminated soil, water, grass, unwashed vegetables, unpasteurized dairy products and undercooked meat | |

| Trichinosis | Trichinella spp. | rodents, pigs, horses, bears, walruses, dogs, foxes, crocodiles, birds | eating undercooked meat | |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium bovis | infected cattle, deer, llamas, pigs, domestic cats, wild carnivores (foxes, coyotes) and omnivores (possums, mustelids and rodents) | milk, exhaled air, sputum, urine, faeces and pus from infected animals | |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis | lagomorphs (type A), rodents (type B), birds

|

ticks, deer flies, and other insects including mosquitoes | |

| West Nile fever | Flavivirus | birds, horses | mosquito bite | |

| Zika fever | Zika virus | chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, monkeys, baboons | mosquito bite, sexual intercourse, blood transfusion and sometimes bites of monkeys | 2015–16 epidemic in the Americas and Oceanic |

See also

- Animal welfare#Animal welfare organizations – Well-being of non-human animals

- Conservation medicine

- Cross-species transmission – Transmission of a pathogen between different species

- Emerging infectious disease – Infectious disease of emerging pathogen, often novel in its outbreak range or transmission mode

- Foodborne illness – Illness from eating spoiled food

- Spillover infection – Occurs when a reservoir population causes an epidemic in a novel host population

- Wildlife disease – diseases in wild animals

- Veterinary medicine – Deals with the diseases of non-human animals

- Wildlife smuggling and zoonoses– Health risks associated with the trade in exotic wildlife

- List of zoonotic primate viruses

References

- ^ a b "zoonosis". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ WHO. "Zoonoses". Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ "A glimpse into Canada's highest containment laboratory for animal health: The National Centre for Foreign Animal Diseases". science.gc.ca. Government of Canada. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

Zoonoses are infectious diseases which jump from a non-human host or reservoir into humans.

- PMID 22229120.

- PMID 25278604.

- PMID 11405938.

- ^ World Health Organization (3 October 2023). "Influenza (Avian and other zoonotic)". who.int. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- PMID 37112960.

- PMID 21912985.

- PMID 26147942.

- PMID 11516376.

- PMID 15525322.

- ^ "Zoonosis". Medical Dictionary. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- PMID 24586500.

- PMID 31002666.

- ISBN 978-0-231-15189-4.

- ^ Agbalaka, P; Ejinaka, O; Etukudoh, NS; Obeta, U; Shaahia, D; Utibe, E (2020). "Zoonotic and Parasitic Agents in Bioterrorism". Journal of Infectious Diseases & Travel Medicine. 4 (2): 1–7. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- PMID 33822740.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus: Fear over rise in animal-to-human diseases". BBC. 6 July 2020. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Preventing the next pandemic – Zoonotic diseases and how to break the chain of transmission". United Nations Environmental Programm. United Nations. 15 May 2020. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- PMID 17368847.

- PMID 16714136.

- S2CID 13384121.

- ^ Med-Vet-Net. "Priority Setting for Foodborne and Zoonotic Pathogens" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- PMID 32684938.

- ^ "Issuing Foodborne Outbreak Notices | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 11 January 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- cdc.gov. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Avian flu: Poultry to be allowed outside under new rules". BBC News. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- PMID 24902957.

- ^ "Mink found to have coronavirus on two Dutch farms – ministry". Reuters. 26 April 2020. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- PMID 16485490.

- S2CID 53092026.

- ^ Carrington D (6 July 2020). "Coronavirus: world treating symptoms, not cause of pandemics, says UN". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-323-95389-4, retrieved 6 March 2023

- S2CID 238588772.

- PMID 32863392.

- ISSN 2201-3008. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- PMID 32359479.

- ^ "WHO Points To Wildlife Farms In Southern China As Likely Source Of Pandemic". NPR. 15 March 2021.

- S2CID 232429241.

- PMID 31986264.

- PMID 16022772.

- PMID 10649986.

- S2CID 43305484.

- PMID 14736926.

- PMID 32937441.

- PMID 9866729.

- ^ Prevention, CDC – Centers for Disease Control and. "Toxoplasmosis – General Information – Pregnant Women". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-8138-1964-8.

- PMID 32266057.

- ^ "Hepatitis E". www.who.int. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- PMID 33371486.

- PMID 32837772.

- PMID 17370509.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005). "Compendium of Measures To Prevent Disease Associated with Animals in Public Settings, 2005: National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians, Inc. (NASPHV)" (PDF). MMWR. 54 (RR–4): inclusive page numbers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "NASPHV – National Association of Public Health Veterinarians". www.nasphv.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ISBN 978-3-319-24442-6

- ^ PMC 7123567.

- ^ "Bushmeat Importation Policies | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 21 November 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- PMID 35550083.

- from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (27 April 2020). "Halt destruction of nature or suffer even worse pandemics, say world's top scientists". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- S2CID 244041854.

- ^ Shield C (16 April 2020). "Coronavirus Pandemic Linked to Destruction of Wildlife and World's Ecosystems". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (5 August 2020). "Deadly diseases from wildlife thrive when nature is destroyed, study finds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Woolaston K, Fisher JL (29 October 2020). "UN report says up to 850,000 animal viruses could be caught by humans, unless we protect nature". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (29 October 2020). "Protecting nature is vital to escape 'era of pandemics' – report". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Escaping the 'Era of Pandemics': experts warn worse crises to come; offer options to reduce risk". EurekAlert!. 29 October 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Factors that may predict next pandemic". ScienceDaily. University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Yong, Ed (28 April 2022). "We Created the 'Pandemicene'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- PMID 33558040.

- ^ Bressan D. "Climate Change Could Have Played A Role In The Covid-19 Outbreak". Forbes. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Early Concepts of Disease". sphweb.bumc.bu.edu. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- PMC 7150340.

- ^ Health (US), National Institutes of; Study, Biological Sciences Curriculum (2007). Understanding Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases. National Institutes of Health (US).

- PMID 18596867.

- PMID 35156099.

- PMID 17507975.

- PMID 17666704.

- S2CID 205694138.

- PMID 11230820.

- PMID 19108397.

- PMID 11334748.

- ^ Basu, Dr Muktisadhan (16 August 2022). "Zoonotic Diseases and Its Impact on Human Health". Agritech Consultancy Services. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ [citation needed]

- ^ "History of Smallpox | Smallpox | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 21 February 2021. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "The Spread and Eradication of Smallpox | Smallpox | CDC". 19 February 2019.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (4 November 2023). "Different types of COVID-19 vaccines: How they work". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Information in this table is largely compiled from: World Health Organization. "Zoonoses and the Human-Animal-Ecosystems Interface". Archived from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ "Bird flu (Avian influenza) - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- PMID 11357156.

- ^ "Why Omicron-infected white-tailed deer pose an especially big risk to humans". Fortune.

- ^ "Haemorrhagic fevers, Viral". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- PMID 6221343.

- ^ PMID 3159089.

- PMID 6316791.

- ^ "Parasites – Leishmaniasis". CDC. 27 February 2019. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Leishmaniasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ a b Clark L. "How Armadillos Can Spread Leprosy". Smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Shute N (22 July 2015). "Leprosy From An Armadillo? That's An Unlikely Peccadillo". NPR. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

Bibliography

- Bardosh K (2016). One Health: Science, Politics and Zoonotic Disease in Africa. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-96148-7..

- Crawford D (2018). Deadly Companions: How Microbes Shaped our History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-881544-0.

- Felbab-Brown V (6 October 2020). "Preventing the next zoonotic pandemic". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Greger M (2007). "The human/animal interface: emergence and resurgence of zoonotic infectious diseases". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 33 (4): 243–299. from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- H. Krauss, A. Weber, M. Appel, B. Enders, A. v. Graevenitz, H. D. Isenberg, H. G. Schiefer, W. Slenczka, H. Zahner: Zoonoses. Infectious Diseases Transmissible from Animals to Humans. 3rd Edition, 456 pages. ASM Press. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C., 2003. ISBN 1-55581-236-8.

- González JG (2010). Infection Risk and Limitation of Fundamental Rights by Animal-To-Human Transplantations. EU, Spanish and German Law with Special Consideration of English Law (in German). Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovac. ISBN 978-3-8300-4712-4.

- Quammen D (2013). ISBN 978-0-393-34661-9.