Art of Mesopotamia

Gudea of Lagash was famous for his numerous portrait sculptures that have been recovered throughout Iraq.

| History of art |

|---|

The art of Mesopotamia has survived in the record from early hunter-gatherer societies (8th millennium BC) on to the Bronze Age cultures of the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian empires. These empires were later replaced in the Iron Age by the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires. Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia brought significant cultural developments, including the oldest examples of writing.

The art of Mesopotamia rivalled

Mesopotamian art survives in a number of forms: cylinder seals, relatively small figures in the round, and reliefs of various sizes, including cheap plaques of moulded pottery for the home, some religious and some apparently not.

Stone

Prehistoric Mesopotamia

The highland regions of Mesopotamia were occupied since the

In Prehistoric and Ancient Mesopotamia, the climate was cooler than in

Art of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period (circa 9000–7000 BC)

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A

Following the Epipalaeolithic period in the Near East, several Pre-Pottery Neolithic A sites are known from the areas of Upper Mesopotamia and the northern mountainous fringes of Mesopotamia, marked by the appearance around 9000 BC on the banks of the Upper Euphrates of the world's oldest known megaliths at Göbekli Tepe,[16] and the first known use of agriculture around the same time at Tell Abu Hureyra, a site from the preceding Natufian culture.[17]

Numerous realistic reliefs and a few sculptures of animals, as well as fragments of reliefs of humans or deities, are known from Göbekli Tepe and dated to circa 9000 BC. The Urfa Man found in another site nearby is dated to the period of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic circa 9000 BC, and is considered as "the oldest naturalistic life-sized sculpture of a human".[13][14][15] Slightly later, early human statuettes in stone and fired clay have been found in other Upper Mesopotamia sites such as Mureybet, dated to 8500–8000 BC.[18][19]

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

Around 8000 BC, during the following period of

In northeastern Mesopotamia, the

-

Jar in calcite alabaster, Syria, late 8th millennium BC.

-

Female statuette, 8th millennium BC, Syria.

-

Alabaster pot Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

First experiments with pottery (circa 7000 BC)

The northern Mesopotamian sites of

Halaf culture (6000–5000 BC, Northwestern Mesopotamia)

Pottery was decorated with abstract geometric patterns and ornaments, especially in the Halaf culture, also known for its clay fertility figurines, painted with lines. Clay was all around and the main material; often modelled figures were painted with black decoration. Carefully crafted and dyed pots, especially jugs and bowls, were traded. As dyes, iron oxide containing clays were diluted in different degrees or various minerals were mixed to produce different colours.

The Halaf culture saw the earliest known appearance of stamp seals.[26] They featured essentially geometric patterns.[26]

Female fertility figurines in painted clay, possibly goddesses, also appear in this period, circa 6000–5100 BC.[27]

-

Jar decorated with diverse geometric patterns; 4900–4300 BC; ceramic; by Halaf culture; Erbil Civilization Museum (Erbil, Iraq)

-

Shard; 5600–5000 BC; painted ceramic; 7.19 × 4.19 cm; by Halaf culture

-

Halaf culture female figurines, 6000–5100 BC Louvre Museum

-

Stamp seal and modern impression- geometric pattern. Halaf culture

Hassuna culture (6000–5000 BC, Northern Mesopotamia)

The Hassuna culture is a Neolithic archaeological culture in northern Mesopotamia dating to the early sixth millennium BC. It is named after the type site of Tell Hassuna in Iraq. Other sites where Hassuna material has been found include Tell Shemshara. The decoration of pottery essentially consists in geometrical shapes, and a few ibex designs.

Samarra culture (6000–4800 BC, Central Mesopotamia)

The Samarra culture is a Chalcolithic archaeological culture in northern Mesopotamia that is roughly dated to 5500–4800 BCE. It partially overlaps with the Hassuna and early Ubaid.

-

Samarra plate, with an abstract rim, a circle of eight fish, and four birds catching four fish that swim towards a central swastika; circa 4000 BC; painted ceramic; diameter: 27.7 cm; Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin

-

Samarra period fine ware, with central Ibex motif; circa 6200–5700 BC; Vorderasiatisches Museum

-

Fragment of Samarra pottery with geometrical designs inUniversity of Chicago Oriental Institute(USA)

Ubaid culture (c. 6500–3800 BC, Southern Mesopotamia)

The Ubaid period (c. 6500–3800 BC)[28] is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid in Southern Mesopotamia, where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.[29]

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvial plain although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium.[30] In the south it has a very long duration between about 6500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the Uruk period.[31]

In North Mesopotamia, Ubaid culture expanded during the period between about 5300 and 4300 BC.

With Ubaid 3 (circa 4500 BC) numerous examples of Ubaid pottery have been found along the Persian Gulf, as far as

Stamps seals start to depict animals in stylistic fashion, and also bear the first known depiction of the Master of Animals at the end of the period, circa 4000 BC.[34][35][36]

-

Jar; Late Ubaid period (4500–4000 BC); pottery; from Southern Iraq; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (USA)

-

Lizard-headed nude woman nursing a child, Ur, Ubaid 4 period, 4500-4000 BCE, Iraq Museum. "The elongated head, similar to the figures found at Eridu, could represent an elaborate headdress or possibly cranial binding".[38]

-

Terracotta stamp seal with Master of Animals motif, Tello, ancient Girsu, End of Ubaid period, Louvre Museum AO14165. circa 4000 BC.[34]

Historic Mesopotamia

Sumerian period (c. 4000–2270 BC)

The rise of the

Pre-Dynastic period: Uruk (c. 4000 to 3100 BC)

The Protoliterate or

Significant works from the southern cities in Sumer proper are the Warka Vase and Uruk Trough, with complex multi-figured scenes of humans and animals, and the Mask of Warka. This is a more realistic head than the Tell Brak examples, like them made to top a wooden body; what survives of this is only the basic framework, to which coloured inlays, gold leaf hair, paint and jewellery were added.[44] It could depict a temple goddess. Shells may have served as the whites of the eyes, and the lapis lazuli, a beautiful, blue semi-precious gemstone, may have formed the pupils.[45] The Guennol Lioness is an exceptionally powerful small figurine of a lion-headed monster,[46] perhaps from the start of the next period.

There are a number of stone or alabaster vessels carved in deep relief, and stone friezes of animals, both designed for temples, where the vessels held offerings. Cylinder seals are already complex and very finely executed and, as later, seem to have been an influence on larger works. Animals shown are often representations of the gods, another continuing feature of Mesopotamian art.[47] The end of the period, despite being a time of considerable economic expansion, saw a decline in the quality of art, perhaps as demand outstripped the supply of artists.[48]

-

Eye idol; 3700–3500 BC; gypsum alabaster; 6.5 × 4.2 × 0.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

TheNational Museum of Iraq (Baghdad)

-

Sculpture of the ritually nude 'Priest-King', Late Uruk, Louvre.

-

Cylinder seal withEgypt-Mesopotamia relations.

-

Tablets with proto-cuneiform pictographic characters, were used for noting commercial transactions (end of 4th millennium BC), Uruk III.

Early artistic exchanges with Egypt (c. 3500–3200 BC)

(3400–3200 BC)

Distinctly Mesopotamian objects and art forms entered Egypt during this period, indicating exchanges and contacts. The designs that were emulated by Egyptian artists are numerous: the Uruk "priest-king" with his tunique and brimmed hat in the posture of the

Pre-Dynastic period: Jemdet Nasr (3100–2900 BC)

The

-

Djemdet Nasr stone bowl, once inlaid with mother-of-pearl, red paste, and bitumen.

-

Cup with Nude Hero, Bulls and Lions, Tell Agrab, Jamdat Nasr to Early Dynastic period, 3000–2600 BC.

-

Stele of lion hunt, Uruk, Iraq, 3000-2900 BCE.National Museum of Iraq

-

The Blau Monuments combine proto-cuneiform characters and illustrations, 3100–2700 BC. British Museum.

Pre-Dynastic dress (4000-2700 BC): kilts and "net-dresses"

The earliest type of dress attested in early

-

Cylinder seal from Uruk, with "net-dress", 3100 BC

-

A "net dress" being worn on the Blau Monuments (3000-2900 BC)

-

A kilt or "net-dress" on the Blau Monuments (3000-2900 BC)

Early Dynastic period (2900–2350 BC)

The Early Dynastic Period is generally dated to 2900–2350 BC. While continuing many earlier trends, its art is marked by an emphasis on figures of worshippers and priests making offerings, and social scenes of worship, war and court life. Copper becomes a significant medium for sculpture, probably despite most works having later being recycled for their metal.[68] Few if any copper sculptures are as large as the Tell al-'Ubaid Lintel, which is 2.59 metres wide and 1.07 metres high.[69]

Many masterpieces have also been found at the Royal Cemetery at Ur (c. 2650 BC), including the two figures of a Ram in a Thicket, the Copper Bull and a bull's head on one of the Lyres of Ur.[70] The so-called Standard of Ur, actually an inlaid box or set of panels of uncertain function, is finely inlaid with partly figurative designs.[71]

A group of 12 temple statues known as the Tell Asmar Hoard, now split up, show gods, priests and donor worshippers at different sizes, but all in the same highly simplified style. All have greatly enlarged inlaid eyes, but the tallest figure, the main cult image depicting the local god, has enormous eyes that give it a "fierce power".[72] Later in the period this geometric style was replaced by a strongly contrasting one giving "a detailed rendering of the physical peculiarities of the subject"; "Instead of sharply contrasting, clearly articulated masses, we see fluid transitions and infinitely modulated surfaces".[73]

-

Sumerian headgear necklaces. British museum.

-

Ram in a Thicket; 2600–2400 BC; gold, copper, shell, lapis lazuli and limestone; height: 45.7 cm; from the Royal Cemetery at Ur; British Museum

-

Bull's head from the Queen's Lyre from Pu-abi's grave, Ur, c. 2600 BC

-

Master of animalsmotif in a panel of the soundboard of the Ur harp

-

Man carrying a box, possibly for offerings. Metalwork, ca. 2900–2600 BCE, Sumer. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

Battle scene, with phalanx led by King Eannatum, on the Stele of the Vultures, Early Dynastic III period, 2600–2350 BC

-

Gold helmet of Meskalamdug, ruler of the First Dynasty of Ur, circa 2500 BC, Early Dynastic period III.

-

Standard of Ur; 2600–2400 BC; shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli on wood; length: 49.5 cm; from the Royal Cemetery at Ur; British Museum

-

Ring of Gold, Carnelian, Lapis Lazuli, Tello, ancient Girsu, mid-3rd millennium BC.

-

A Sumerian group of two separate shell inlay fragments forming the body and head of a sheep. Circa 27th - 24th Century BC. From a Mayfair gallery, London, UK.

Akkadian Empire period (c. 2271–2154 BC)

The

King Naram-Sin's famous Victory Stele depicts him as a god-king (symbolized by his horned helmet) climbing a mountain above his soldiers, and his enemies, the defeated Lullubi. Although the stele was broken off at the top when it was stolen and carried off by the Elamite forces of Shutruk-Nakhunte, it still strikingly reveals the pride, glory, and divinity of Naram-Sin. The stele seems to break from tradition by using successive diagonal tiers to communicate the story to viewers, however, the more traditional horizontal frames are visible on smaller broken pieces. It is 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 m) tall, and made from pink sandstone.[81][82] From the same reign, the bare legs and lower torso of the copper Bassetki Statue show an unprecedented level of realism, as does the imposing bronze head of a bearded ruler (Louvre).[83]

The Louvre head is a life-size, bronze bust found in Nineveh. The intricate curling and patterning of the beard and the complex hairstyle suggests royalty, power, and wealth from an ideal male in society. Aside from its aesthetic traits, this piece is spectacular because it is the earliest hollow-cast sculpture item known to use the lost-wax casting process.[84] There is deliberate damage on the left side of the face and eye, indicating that the bust was intentionally slashed at a later period to demonstrate political iconoclasm.[85]

-

Bronze head of an Akkadian ruler, discovered in Nineveh in 1931, presumably depicting either Sargon of Akkad or Sargon's grandson Naram-Sin.[86]

-

The copper Bassetki Statue

-

Akkadian language inscription on the obelisk of Manishtushu

-

Detail of a victory stele of Akkadian king Rimush

-

Seal impression with gods andIndus-Mesopotamia relationsat the time.

-

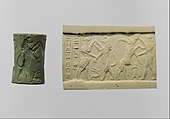

Cylinder seal and modern impression – bull-man combatting lion; nude hero combatting water buffalo; 2250–2150 BC; albite; height: 3.4 cm, diameter: 2.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

GoddessIshtaron an Akkadian Empire seal, 2350–2150 BC. She is equipped with weapons in her back, has a horned helmet, and is trampling a lion.

Neo-Sumerian period (c. 2112–2004 BC)

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, a local dynasty emerged in Lagash. Gudea, ruler of Lagash (reign ca. 2144 to 2124 BC), was a great patron of new temples early in the period, and an unprecedented 26 statues of Gudea, mostly rather small, have survived from temples, beautifully executed, mostly in "costly and very hard diorite" stone. These exude a confident serenity.[88]

The northern Royal Palace of Mari produced a number of important objects from before about 1800 BC, including the Statue of Iddi-Ilum,[89] and the most extensive remains of Mesopotamian palace frescos.[90]

The Neo-Sumerian art of the Third Dynasty of Ur reached new heights, especially in terms of realism and fine craftmanship.

-

Statue of Gudea P; circa 2090 BC; diorite; height: 44 cm, width: 21.5 cm, depth: 29.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Portrait ofLouvre Museum

-

Ur-Namma holding a basket; 2112-2095 BC; copper alloy; height: 27.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art(New York City)

-

Seal of Hash-hamer, showing enthroned king Ur-Nammu, with modern impression; circa 2100 BC; greenstone; height: 5.3 cm; British Museum (London)

Amorite and Kassite periods (c. 2000–1100 BC)

The political history of this period of nearly 1000 years is complicated, marked by the rise of

Isin-Larsa period (c. 2000–1800 BC)

The Isin-Larsa period is a period of turmoil, marked by the rise of the influence of the Amorites for the northwest of Mesopotamia. Life was often unstable, and non-Sumerian invasions a recurring theme.

-

Cylinder seal and modern impression. Presentation scene, c. 2000–1750 B.C. Isin-Larsa

-

KingIshtar. Circa 2000 BCE.

-

Four-faced god, Ishchali, Isin-Larsa to Old Babylonia periods, 2000–1600 BC, bronze - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago

First Babylonian Dynasty (1830–1531 BC)

From the 18th century BC,

The Burney Relief is an unusual, elaborate, and relatively large (20×15 inches) terracotta plaque of a naked winged goddess with the feet of a bird of prey, and attendant owls and lions. It comes from the 18th or 19th century BC, and may also be moulded. Similar pieces, small statues or reliefs of deities, were made for altars in homes or small wayside shrines, and small moulded terracotta ones were probably available as souvenirs from temples.[95]

The Investiture of Zimri-Lim, now in the Louvre, is a large palace fresco that is the outstanding survival of Mesopotamian wall-painting, although comparable schemes were probably common in palaces.

After the death of Hammurabi, the first Babylonian dynasty lasted for another century and a half, but his empire quickly unravelled, and Babylon once more became a small state. The Amorite dynasty ended in 1595 BC, when Babylonia fell to the Hittite king Mursilis, after which the Kassites took control.

-

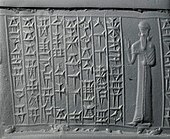

Hammurabi (standing), depicted as receiving his royal insignia from Shamash (or possibly Marduk). Hammurabi holds his hands over his mouth as a sign of prayer[96] (relief on the upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws).

-

Detail of a limestone votive monument from Sippar, Iraq, dating to c. 1792 – c. 1750 BC showing King Hammurabi raising his right arm in worship, now held in the British Museum

-

"The Worshipper of Larsa", a votive statuette dedicated to the god Amurru for Hammurabi's life; circa 1760 BC; bronze and gold; 19 x 15 cm; Louvre

-

Cylinder seal, ca. 18th–17th century BC. Babylonia

Kassites (1600–1155 BC)

The original homeland of the Kassites is not well-known, but appears to have been located in the

-

Kassite king Meli-Shipak II on his throne on a kudurru-Land grant to Ḫunnubat-Nanaya. The eight-pointed star was Inanna-Ishtar's most common symbol. Here it is shown alongside the solar disk of her brother Shamash (Sumerian Utu) and the crescent moon of her father Sin(Sumerian Nanna).

-

KassiteLouvre Museum.

-

Cylinder seal of Kassite king Kurigalzu II (c. 1332–1308 BC). Louvre Museum AOD 105

-

Kassite cylinder seal, ca. 16th–12th century BC.

Assyrian period (c. 1500 – 612 BC)

An Assyrian artistic style distinct from that of Babylonian art, which was the dominant contemporary art in Mesopotamia, began to emerge c. 1500 BC, well before their empire included Sumer, and lasted until the fall of Nineveh in 612 BC.

The conquest of the whole of Mesopotamia and much surrounding territory by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC) created a larger and wealthier state than the region had known before, and very grandiose art in palaces and public places, no doubt partly intended to match the splendour of the art of the neighbouring Egyptian empire. From around 879 BC the Assyrians developed a style of extremely large schemes of very finely detailed narrative low reliefs in stone or gypsum alabaster, originally painted, for palaces. The precisely delineated reliefs concern royal affairs, chiefly hunting and war making. Predominance is given to animal forms, particularly horses and lions, which are magnificently represented in great detail.

Human figures are comparatively rigid and static but are also minutely detailed, as in triumphal scenes of sieges, battles, and individual combat. Among the best known Assyrian reliefs are the famous Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal scenes in alabaster, and the Lachish reliefs showing a war campaign in Palestine, both of which are of the 7th century BC, from Nineveh and now in the British Museum.[99] Reliefs were also carved into rock faces, as at Shikaft-e Gulgul, a style which the Persians continued.

The Assyrians produced relatively little sculpture in the round, with the partial exception of colossal human-headed lamassu guardian figures, with the bodies of lions or bulls, which are sculpted in high relief on two sides of a rectangular block, with the heads effectively in the round (and often also five legs, so that both views seem complete). These marked fortified royal gateways, an architectural form common throughout Asia Minor. A single statue of a nude female is known. The Assyrian form of the winged genie, winged spirits with bearded human heads seen in reliefs, influenced Ancient Greek art, which in its "orientalizing period" added various winged mythological beasts including the Chimera, griffin and winged horses (Pegasus) and men (Talos).[100] Many carry the bucket and cone.

Even before dominating the region the Assyrians had continued the cylinder seal tradition with designs which are often exceptionally energetic and refined.[101] At Nimrud the carved Nimrud ivories and bronze bowls were found that are decorated in the Assyrian style but were produced in several parts of the Near East including many by Phoenician and Aramaean artisans.

-

Shalmaneser III, on the Throne Dais of Shalmaneser III at the Iraq Museum.

-

Afeather robed archerholding a bow instead of a ring (9th-8th century BC)

-

7th-century BC relief depicting Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BC) and three royal attendants in a chariot. From the North Palace at Nineveh

-

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III. The king, surrounded by his royal attendants and a high-ranking official, receives a tribute from Sua, king of Gilzanu (north-west Iran), who bows and prostrates before the king. From Nimrud

-

Illustration of a hall in the Assyrian Palace of Ashurnasrirpal II by Austen Henry Layard (1854)

-

Sargon II and dignitary. Low-relief from the L wall of the palace of Sargon II at Dur Sharrukin in Assyria (modern-day Khorsabad in Iraq), c. 716–713 BC.

-

Glazed terracotta tile from Nimrud, with a court scene, British Museum

-

Relief with a winged genie with bucket and cone; 713-706 BC; height: 3.3 m

-

Lion weight; 6th-4th century BC; bronze; height: 29.5 cm, Louvre

-

Assyrian ornaments and patterns, illustrated in a book from 1920

Neo-Babylonian period (626–539 BC)

The famous Ishtar Gate, part of which is now reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, was the main entrance into Babylon, built in about 575 BC by Nebuchadnezzar II, the king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, who exiled the Jews; the empire lasted from 626 BC to 539 BC. The walls surrounding the entrance way are decorated with rows of large relief animals in glazed brick, which has therefore retained its colours. Lions, dragons and bulls are represented. The gate was part of a much larger scheme for a processional way into the city, from which there are sections in many other museums.[102] Large wooden gates throughout the period were strengthened and decorated with large horizontal metal bands, often decorated with reliefs, several of which have survived, such as the various Balawat Gates.

Other traditional types of art continued to be produced, and the Neo-Babylonians were very keen to stress their ancient heritage. Many sophisticated and finely carved seals survive. After Mesopotamia fell to the

-

Detail of Nebuchadnezzar II's Building Inscription plaque of the Ishtar Gate, from Babylon, Iraq. 6th century BCE. Pergamon Museum

-

Female head; circa 2000-1600 BC; ceramic; 18 x 12.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Facade of the Throne Room. Babylon, coloured, glazed bricks. 604-562 BCE. The Throne-Room was situated in the third courtyard complex of the royal palace.

-

Black basalt monument of king Esarhaddon. It narrates Esarhaddon's restoration of Babylon. Circa 670 BCE.

-

Cylinder seal with an impression; circa 18th–17th century BC; hematite; 2.39 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

A partial view of the ruins of Babylon.

-

Male head; circa late 8th–early 7th century; ceramic; 12.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Remains of brick structures in Babylon

-

Babylonian Map of the World, 6th century BC clay tablet

Characteristics

The central place of worship was the ziggurat, a stepped pyramid with stairs leading to an altar where worshipers would elevate themselves closer to the heavens.

Sculptures, mostly rather small, are the main surviving artworks. In the late period Assyrian sculpture for palaces was often very large. Most of the Sumerian and Akkadian statues of figures are in a position of prayer. The main types of stone used are limestone and alabaster.

Zainab Bahrani said that visual art in Babylonia and Assyria was not intended to simply imitate or replicate reality, the goal was to produce a representation that acted as a stand-in or substitute for the real thing. This representation was then perceived as part of actual reality.[104]

Architecture

Ancient Mesopotamia is most noted for its construction of mud brick buildings and the construction of ziggurats, occupying a prominent place in each city and consisting of an artificial mound, often rising in huge steps, surmounted by a temple. The mound was no doubt to elevate the temple to a commanding position in what was otherwise a flat river valley. The great city of Uruk had a number of religious precincts, containing many temples larger and more ambitious than any buildings previously known.[105]

The word ziggurat is an anglicized form of the Akkadian word ziqqurratum, the name given to the solid stepped towers of mud brick. It derives from the verb zaqaru, ("to be high"). The buildings are described as being like mountains linking Earth and heaven. The Ziggurat of Ur, excavated by Leonard Woolley, is 64 by 46 meters at base and originally some 12 meters in height with three stories. It was built under Ur-Nammu (circa 2100 B.C.) and rebuilt under Nabonidus (555–539 B.C.), when it was increased in height to probably seven stories.[106]

Assyrian palaces had a large public court with a suite of apartments on the east side and a series of large banqueting halls on the south side. This was to become the traditional plan of Assyrian palaces, built and adorned for the glorification of the king.

-

The Ziggurat of Ur, approximately 21st century BC, Ur)

-

Illustration of a hall in the Assyrian Palace of Ashurnasrirpal II by Austen Henry Layard (1854)

-

Mosaic panel (using stone cones) decorating a wall of one of the temple at the city of Warka (Uruk), Iraq. 2nd half of the 4th millennium BCE. Iraq Museum

-

Assyrian reliefs from the Palace of Sargon II inOriental Institute Museum (Chicago, USA)

-

Terracotta model of a house from Babylon, 2600 BCE

Jewellery

The preferred jewellery designs used in

). A number of documents have been found that relate to the trade and production of jewellery from Sumerian sites.Later Mesopotamian jewellers and craftsmen employed metalworking techniques such as cloisonné, engraving, granulation, and filigree. The large variety and size of necklaces, bracelets, anklets, pendants, and pins found may be due to the fact that jewellery was worn by both men and women, and perhaps even children.

-

Pair of earrings; 2600–2500 BC; gold; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Necklace beads; 2600–2500 BC; gold and lapis lazuli; length: 54 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of earrings with cuneiform inscriptions, 2093–2046 BC; gold; Sulaymaniyah Museum (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq)

-

Sumerian necklaces and headgear discovered in the royal (and individual) graves of the Royal Cemetery at Ur, showing the way they may have been worn, in British Museum (London)

Collections

Important collections include the

Several other museums have good collections, especially of the very numerous cylinder seals. Syrian museums have important collections from sites in modern Syria. Other museums with important collections of Mesopotamian art are: the

-

The Assyrian gallery at the Iraq Museum, Baghdad

-

A room with Mesopotamian art, from the Louvre

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Frankfort, 124-126

- ^ Frankfort, Chapters 2–5

- ^ Convenient summaries of the typical motifs of cylinder seals in the main periods are found throughout in Teissier

- ^ Frankfort, 66–74

- ^ Frankfort, 71–73

- ^ Frankfort, 66–74; 167

- ISBN 9781576071861. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-07-30. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ Edwards, Owen (March 2010). "The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ISBN 9780870994708. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ "Horse from Hayonim Cave, Israel, 30,000 years" in Israel Museum Studies in Archaeology. Samuel Bronfman Biblical and Archaeological Museum of the Israel Museum. 2002. p. 10. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ "Hayonim horse". museums.gov.il. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ ISBN 9783319484020. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- ^ ISBN 9782271081872. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- ^ ISBN 9781591438359. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- ISBN 9781107006690. Archivedfrom the original on 2019-11-12. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "The Earliest Uses of Clay in Syria | Expedition Magazine". www.penn.museum. Archived from the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ISBN 9780306471667. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ISBN 9782804159238. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2019-04-22. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ ISBN 9781134863280. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ISBN 9783030029500. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ISBN 9781575060422. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr. Archived from the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- ^ For Jarmo pottery photograph, see "A Dish from the Jarmo Culture". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2021-07-27. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ ISBN 9781614510352. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr. Archived from the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0p. 2; "Radiometric data suggest that the whole Southern Mesopotamian Ubaid period, including Ubaid 0 and 5, is of immense duration, spanning nearly three millennia from about 6500 to 3800 B.C."

- ^ Hall, Henry R. and Woolley, C. Leonard. 1927. Al-'Ubaid. Ur Excavations 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Adams, Robert MCC. and Wright, Henry T. 1989. 'Concluding Remarks' in Henrickson, Elizabeth and Thuesen, Ingolf (eds.) Upon This Foundation - The ’Ubaid Reconsidered. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 451–456.

- ^ a b Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham. 2010. 'Deconstructing the Ubaid' in Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham (eds.) Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 2.

- ISBN 9781405137232. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-01-09. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- ISBN 9781315511160. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-02-25. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ a b "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr. Archived from the original on 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ISBN 9781614510352. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ISBN 9781134530779. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-03-03. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr. Archived from the original on 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ^ The Looting Of The Iraq Museum Baghdad The Lost Legacy Of Ancient Mesopotamia. 2005. p. Chapter III.

- ^ Crawford 2004, p. 69

- ^ Crawford 2004, p. 75

- ^ Frankfort, 27

- ^ Frankfort, 241-242

- ^ Frankfort, 24, 242

- ^ Frankfort, 24-28, 31-32

- ISBN 9780134479279.

- ^ Frankfort, 32-33

- ^ Frankfort, 28-37

- ^ Frankfort, 36-39

- ^ Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 25.

- ^ The Looting Of The Iraq Museum Baghdad The Lost Legacy Of Ancient Mesopotamia. 2005. p. viii.

- ISBN 0-495-00479-0.

- ISBN 9781588390431.

- ^ "Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin". repository.edition-topoi.org. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ^ "Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin". repository.edition-topoi.org. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ISBN 9780931464966. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-12-09. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ISBN 9781444333503. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-06-18. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ^ Shaw, Ian. & Nicholson, Paul, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 109.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Larkin. "Earliest Egyptian Glyphs". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ISBN 9781444333503. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ISBN 9780931464966. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-05-20. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ISBN 9781444342345. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-05-22. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ISBN 9780520203075. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-136-21911-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- from the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ^ Frankfort, 55

- ^ Frankfort, 60–61

- ^ Frankfort, 61–66

- ^ Frankfort, 71-76

- National Museum of Iraq(with the god).

- ^ Frankfort, 55-60, 55 quoted

- ^ Louvre Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine Pouysségur, Patrick , ed. "Perforated Relief of King Ur-Nanshe." Louvre Museum. Louvre Museum. Web. 13 Mar 2013.

- ^ Transliteration: "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-09-25. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ Similar text: "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-09-25. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ISBN 978-90-04-06248-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- JSTOR 4196708.

- ^ Frankfort, 83–91

- ^ Frankfort, 91

- ISBN 0-534-64095-8.

- ^ Frankfort, 86

- ^ Frankfort, 91

- ISBN 9780134479279.

- S2CID 193037843.

- ^ M. E. L. Mallowan, "The Bronze Head of the Akkadian Period from Nineveh Archived 2020-04-21 at the Wayback Machine", Iraq Vol. 3, No. 1 (1936), 104–110.

- JSTOR 4171539.

- ^ Frankfort, 93 (quoted)-99

- ^ Frankfort, 114–119

- ^ Frankfort, 124-126

- ^ Frankfort, 127

- ^ Frankfort, 93

- ^ Frankfort, 110-116, 126

- ISBN 9780141938257. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Frankfort, 110–112

- ISBN 9780141938257, archivedfrom the original on 2019-12-23, retrieved 2019-08-20

- ^ Frankfort, 102-126

- ^ Frankfort, 130

- ^ Frankfort, 141–193

- ^ Frankfort, 205

- ^ Frankfort, 141–193

- ^ Frankfort, 203–205

- ^ Frankfort, 348-349

- ISBN 978-965-221-084-5.

- ISBN 978-1-3500-9212-9.

- ^ "Gods and Goddesses". Mesopotamia.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 November 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-78240-169-8.

Sources

- ISBN 9780521533386.

- ISBN 0140561072

- Teissier, Beatrice, Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals from the Marcopolic Collection, 1984, University of California Press, ISBN 0520049276, 9780520049277, google books

Further reading

- Iraq Arts and Culture

- Collon, Dominique; Oates, Joan; Crawford, Harriet; Green, Anthony; Oates, David; Russell, John M.; Roaf, Michael; Keall, E. J.; Amiet, Pierre; Curtis, John; Moon, Jane; Nunn, A. (2003). "Mesopotamia". ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. (subscription or UK public library membershiprequired)

- Crawford, Vaughn E.; et al. (1980). Assyrian reliefs and ivories in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: palace reliefs of Assurnasirpal II and ivory carvings from Nimrud. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870992600.

![Calcite tripod vase, mid-Euphrates, probably from Tell Buqras, 6000 BC, Louvre Museum AO 31551.[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7a/Calcite_tripod_vase%2C_mid-Euphrates_probably_from_Tell_Buqras%2C_6000_BCE%2C_Louvre_Museum_AO_31551.jpg/168px-Calcite_tripod_vase%2C_mid-Euphrates_probably_from_Tell_Buqras%2C_6000_BCE%2C_Louvre_Museum_AO_31551.jpg)

![Fragment of pottery with a painting of an Ibex; 4700–4200 BC; painted ceramic; from Girsu; Louvre[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Ubaid_IV_pottery_4700-4200_BC_Tello%2C_ancient_Girsu%2C_Louvre_Museum.jpg/115px-Ubaid_IV_pottery_4700-4200_BC_Tello%2C_ancient_Girsu%2C_Louvre_Museum.jpg)

![Lizard-headed nude woman nursing a child, Ur, Ubaid 4 period, 4500-4000 BCE, Iraq Museum. "The elongated head, similar to the figures found at Eridu, could represent an elaborate headdress or possibly cranial binding".[38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Lizard-headed_nude_woman_nursing_a_child%2C_from_Ur%2C_Iraq%2C_c._4000_BCE._Iraq_Museum_%28retouched%29.jpg/108px-Lizard-headed_nude_woman_nursing_a_child%2C_from_Ur%2C_Iraq%2C_c._4000_BCE._Iraq_Museum_%28retouched%29.jpg)

![Terracotta stamp seal with Master of Animals motif, Tello, ancient Girsu, End of Ubaid period, Louvre Museum AO14165. circa 4000 BC.[34]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Stamp_seal_with_Master_of_Animals_motif%2C_Tello%2C_ancient_Girsu%2C_End_of_Ubaid_period%2C_Louvre_Museum_AO14165_%28detail%29.jpg/164px-Stamp_seal_with_Master_of_Animals_motif%2C_Tello%2C_ancient_Girsu%2C_End_of_Ubaid_period%2C_Louvre_Museum_AO14165_%28detail%29.jpg)

![Sumerian dignitary, Uruk, circa 3300-3000 BCE. National Museum of Iraq.[49][50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Priest-king_from_Uruk%2C_Mesopotamia%2C_Iraq%2C_c._3000_BCE._The_Iraq_Museum.jpg/151px-Priest-king_from_Uruk%2C_Mesopotamia%2C_Iraq%2C_c._3000_BCE._The_Iraq_Museum.jpg)

![The original Warka Vase, in the National Museum of Iraq. It is one of the earliest surviving works of narrative relief sculpture, dated to c. 3200–3000 BC.[51]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/67/Warka_vase_%28background_retouched%29.jpg/72px-Warka_vase_%28background_retouched%29.jpg)

![Cylinder seal impression from Uruk, showing a "king-priest" in brimmed hat and long coat feeding the herd of goddess Inanna, symbolized by two rams, framed by reed bundles as on the Uruk Vase. Late Uruk period, 3300–3000 BC.[52][53] A similar king-priest also appears standing on a ship.[54]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bc/Rolzegel.JPG/170px-Rolzegel.JPG)

![King Ur-Nanshe, seated, wearing flounced skirt. Limestone, Early Dynastic III (2550–2500 BC). Found in Telloh (ancient city of Girsu). Louvre Museum.[74][75][76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Ur-Nanshe.jpg/123px-Ur-Nanshe.jpg)

![Statue of Iku-Shamagan king of Mari, c.2500 BC.[77][78] National Museum of Damascus](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Iku-Shamagan_-_Mari_-_Temple_of_Ninni-Zaza_%28front_and_side%29.jpg/162px-Iku-Shamagan_-_Mari_-_Temple_of_Ninni-Zaza_%28front_and_side%29.jpg)

![Bronze head of an Akkadian ruler, discovered in Nineveh in 1931, presumably depicting either Sargon of Akkad or Sargon's grandson Naram-Sin.[86]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Sargon_of_Akkad_%28frontal%29.jpg/122px-Sargon_of_Akkad_%28frontal%29.jpg)

![Naked captives, on the Nasiriyah stele of Naram-Sin.[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/Nasiriyah_Victory_Stele_of_Naram-Sin%2C_from_Mesopotamia%2C_Iraq%2C_c._2300_BCE._Iraq_Museum.jpg/170px-Nasiriyah_Victory_Stele_of_Naram-Sin%2C_from_Mesopotamia%2C_Iraq%2C_c._2300_BCE._Iraq_Museum.jpg)

![Hammurabi (standing), depicted as receiving his royal insignia from Shamash (or possibly Marduk). Hammurabi holds his hands over his mouth as a sign of prayer[96] (relief on the upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws).](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/98/F0182_Louvre_Code_Hammourabi_Bas-relief_Sb8_rwk.jpg/154px-F0182_Louvre_Code_Hammourabi_Bas-relief_Sb8_rwk.jpg)